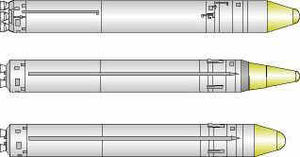

The UR-100N, also known as RS-18A, is an intercontinental ballistic missile in service with Soviet and Russian Strategic Missile Troops. The missile was given the NATO reporting name SS-19 Stiletto and carries the industry designation 15A30.[5]

| UR-100N SS-19 Stiletto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | ICBM |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1975–present |

| Used by | Russian Strategic Missile Troops |

| Production history | |

| Designer | NPO Mashinostroyeniya |

| Manufacturer | Khrunichev Machine-Building Plant |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 126.3 t (278,000 lb) |

| Length | 27.5 m (90 ft 3 in) |

| Diameter | 2.48 m (8 ft 2 in) |

| Warhead | 1 x 1 Mt or 6 x 400 kt[1] |

| Engine | two-stage liquid fuel |

Operational range | 10,600 kilometres (6,600 mi) |

| Maximum speed | 7.64 km/s (4.75 mi/s) |

Guidance system | inertial |

| Accuracy | CEP 300 m |

Development

editDevelopment of the UR-100N began at OKB-52 in 1970 and flight tests were carried out from 1973 through 1975. In 1976, the improved UR-100NUTTKh (NATO designation SS-19 Mod 3) version entered development with flight tests in the later half of the decade. The rocket's control system was developed at NPO "Electropribor"[6] (Kharkiv, Ukraine).

Description

editThe UR-100N is a fourth-generation silo-launched liquid-propellant ICBM similar to the UR-100 but with much increased dimensions, mass, performance, and payload. The missile was not designed to use existing UR-100 silos, and therefore had new silos constructed for it.

The missile has a preparation time to start of 25 minutes, a storage period of 22 years, and 6 MIRVs.[7]

Operational history

editThe UR-100N reached initial operating capability in 1974, and by 1978 an inventory of 190 launchers were reached. In 1979, the UR-100UTTKh became operational and by 1983 had replaced many older missiles and reached a maximum inventory of 360 launchers. This had fallen to 300 by 1991, and with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, many in Ukraine became property of that nation. 170 remained in Russia, although treaty obligations required the rearming of the missiles with single warheads. As of 2018, the Strategic Missile Troops had 20 (or more likely just 10) UR-100NUTTKh in active service.[8] Recent political developments have led to rearmament of the missiles with the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicles (HGVs) (NATO designation SS-19 Mod 4)[9][1] On 27 December 2019, the first missile regiment armed with the Avangard HGV officially entered combat duty.[10]

The units previously held by Ukraine have been returned to Russia or decommissioned.

US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center estimates that as of June 2017 about 50 Mod 3 launchers were operationally deployed.[11]

Civil application

editThe UR-100N forms the basis of the Rokot space launch system, which was used in several successful launches in the 1990s and early 2000s (decade), and one failed launch of the ESA CryoSat satellite in 2005. After the failure, Rokot launches were suspended. Once the cause was unambiguously identified and corrective measures implemented, Rokot returned to active service on 28 July 2006, with the successful launch of an earth observation satellite for South Korea.

START I treaty

editThe START I treaty was signed by the Soviet Union in 1991. The treaty required the Soviet Union to begin the process of dismantling nuclear warheads and the launchers used for UR-100N missiles.[12] The Soviet Union had 300 100NUTTH missiles stationed in both Russia and Ukraine: 130 deployed in Ukraine, and the rest scattered around Russia.[13] After the fall of the USSR, Ukraine claimed ownership of all the missiles locating in its territory. Ukraine then began dismantling launchers for the UR-100N missiles in compliance with the START I treaty. Nuclear warheads that were deployed in Ukraine were also dismantled following terms of the treaty.[14]

Operators

editThe Strategic Missile Troops are the only operator of the UR-100N. As of March 2020,[15] 2 silo-based UR-100NUTTKh missiles with Avangard HGV are deployed with:

Former operators

edit- The Armed Forces of Ukraine inherited a number of missiles from the Soviet Union and turned them over to Russia.[16]

After the Budapest Memorandum was signed in 1994, the 43rd Rocket Army shipped more than 1,326 warheads from its nuclear storage depots: 675 warheads in 1994, 477 in 1995 and 174 in 1996. On May 31, 1996, the final train left Ukraine for Russia laden with the last of approximately 1,800 warheads, including more than 400 weapons from the 46th Bomber Army."[17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Kristensen, Hans M.; Norris, Robert S. (January 2015). "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 71 (3): 84–97. doi:10.1177/0096340215581363. S2CID 145329451.

- ^ a b "RD-0233, RD-0234, RD-0235, RD-0236, RD-0237. Intercontinental ballistic missiles RS-18". KBKhA. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ a b Zak, Anatoly. "UR-100N Family". RussianSpaceWeb.com. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ "RD-0237". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ "UR-100 (SS-19)". Missile Threat.

- ^ "Krivonosov, Khartron: Computers for rocket guidance systems". web.mit.edu.

- ^ "Russian Ballistic Missiles, баллистические ракеты России". Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Norris, Robert S. (30 April 2018). "Russian nuclear forces, 2018". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 74 (3): 185–195. Bibcode:2018BuAtS..74c.185K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2018.1462912.

- ^ xavier. "Russia launched serial production of Avangard hypersonic missile - March 2018 Global Defense Security army news industry - Defense Security global news industry army 2018 - Archive News year". armyrecognition.com.

- ^ Первый ракетный полк "Авангарда" заступил на боевое дежурство [The first Avangard missile regiment took up combat duty]. TASS (in Russian). 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat". Defense Intelligence Ballistic Missile Analysis Committee. 2017.

- ^ Goodby, James (1998). Europe undivided: the new logic of peace in U.S.-Russian relations. Washington D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press. p. 81.

- ^ Pike, John. "UR-100N / SS-19 STILLETO". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Podvig, Pavel (2004). Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. MIT. p. 223. ISBN 9780262661812.

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt (9 March 2020). "Russian nuclear forces, 2020". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 76 (2): 73–84. Bibcode:2020BuAtS..76b.102K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2020.1728985.

- ^ Podvig, Pavel (2001). Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. Cambridge: The MIT Press. pp. 220–223. ISBN 9780262661812.

- ^ Hanrahan 2014, p. 135.

External links

edit