60°07.05′N 001°58.30′W / 60.11750°N 1.97167°W

RMS Oceanic

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Oceanic |

| Builders | Harland and Wolff |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | |

| Succeeded by | Big Four class |

| In service | 1899–1914 |

| Completed | 1 |

| Lost | 1 |

| History | |

| Name |

|

| Owner | White Star Line |

| Operator |

|

| Route | Liverpool–Cobh–New York (1899-1907) and Southampton-Cherbourg-New York (1907-1914) |

| Builder | Harland and Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number | 317 |

| Laid down | 1897 |

| Launched | 14 January 1899 |

| Completed | 26 August 1899 |

| Maiden voyage | 6 September 1899 |

| Out of service | 8 September 1914 |

| Fate | Ran aground off Foula, Shetland, 8 September 1914 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 17,274 GRT, 6,996 NRT |

| Length | 704 ft (215 m) |

| Beam | 68.4 ft (20.8 m) |

| Installed power | Triple expansion reciprocating engines; 28,000 hp (21,000 kW) |

| Propulsion | Two propellers |

| Speed |

|

| Capacity |

|

| Crew | 349 |

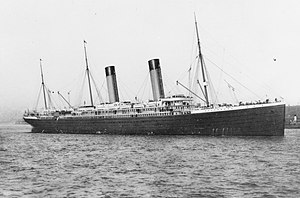

RMS Oceanic was a transatlantic ocean liner built for the White Star Line. She sailed on her maiden voyage on 6 September 1899 and was the largest ship in the world until 1901.[1] At the outbreak of World War I she was converted into an armed merchant cruiser. On 8 August 1914 she was commissioned into Royal Navy service.

On 25 August 1914, the newly designated HMS Oceanic departed Southampton to patrol the waters from the North Scottish mainland to Faroe. On 8 September she ran aground and was wrecked off the island of Foula, in the Shetland Islands.

Background

editIn the late 1890s the White Star Line's existing prestige ocean liners Majestic and Teutonic, both launched in 1889, had become outmoded due to rapid advances in marine technology: Their competitors, the Cunard Line, had introduced the Campania and Lucania in 1893, and from 1897 the German Norddeutscher Lloyd began introducing four new Kaiser-class ocean liners which included the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. In order to compete with these ships the White Star Line needed to produce a new flagship which could rival them. In 1897 White Star put Cymric into service. She was bigger than the Teutonic and Majestic, but not the largest in the world. Cymric was larger than Campania and Lucania, but not faster. Cymric introduced the strategy of luxury over speed. White Star Line used this strategy on the Oceanic.[2]

Design and construction

editThe RMS Oceanic was built at Harland and Wolff’s Queen's Island yard at Belfast, as was the tradition with White Star Line ships, and her keel was laid down in 1897. She used the luxury over speed strategy, which first began with the Cymric in 1897. She was named after their first successful liner Oceanic of 1870, and was to be the first ship to exceed Brunel's Great Eastern in length, although not in tonnage. At 17,272 gross register tons, the future "Queen of the Ocean" cost one million pounds sterling[a] and required 1,500 shipwrights to complete. However, Oceanic was not designed to be the fastest ship afloat or compete for the Blue Riband, as it was the White Star Line's policy to focus on size and comfort rather than speed. Oceanic was designed for a service speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). She was powered by two four-cylinder triple expansion engines, which were when constructed the largest of their type in the world, and could produce 28,000 indicated horsepower (21,000 kW).[4][5][2]

In order to build the ship a new 500 ton overhead gantry crane had to be constructed at the yard in order to lift the material necessary for the ship's construction. Another innovation was the use of hydraulic riveting machines, which were used for the first time at Harland and Wolff during her construction.[2]

Oceanic's bridge was integrated with her superstructure, giving her a clean fluid look; this design feature would be omitted from the next big four White Star ships, Cedric, Celtic, Baltic and Adriatic, with their odd but distinguishable 'island' bridges. "Nothing but the very finest" was Ismay's policy toward this new venture.[6] The architect Richard Norman Shaw was employed as the consultant for the design of much of the interiors of the ship, which were lavishly decorated in the first-class sections.[2]

Oceanic was built to accommodate 1,710 passengers: 410 First Class, 300 Second Class and 1,000 Third Class, plus 349 crew.[2] In his autobiography Titanic and Other Ships,[7] Charles Lightoller gives an account of what it was like to be an officer on this vessel.

Her passenger accommodations were laid out in a manner similar to that of Teutonic and Majestic, with First Class amidships, Second Class situated at the aft end of the superstructure and Third Class divided at the forward and aft ends of the vessel on four decks; Promenade, Upper, Saloon and Main. First Class occupied spaces on all four decks, most of which was dedicated to an array of spacious and comfortable single, two-berth and three-berth cabins. There was a library on the Promenade Deck and a smoke room at the aft end of the Upper Deck, with the most impressive feature being the elegant dome which capped the First Class dining room on the Saloon Deck.[8] The First Class Dining Room boasted both a piano and an organ. There were berths for valets and ladies' maids in close proximity to the first class accommodation.[9]

Similar to what was seen aboard Teutonic and Majestic, Second Class accommodations aboard were of more modest elegance, but spacious and comfortable. A separate deckhouse at the aft end of the superstructure provided both open and closed promenade decks and housed a library and smoke room which were scaled-down versions of their First Class counterparts. The same scaling-down was seen with the Second Class dining room, which could seat 148, and the array of comfortable two-berth and four-berth cabins.

Third Class, as was customary on all White Star Line vessels on the North Atlantic, strictly segregated at opposite ends of the vessel on the Upper, Saloon and Main decks. On the Upper Deck, entrances were located adjacent to the forward and aft well decks, where most of the lavatories were located. At the very aft end of the deck were the Third Class Smoke Room and General Room, as well as the galley. Single men were berthed in five compartments at the forward end of the vessel (two on the Saloon deck, three on the Main deck), each of which were laid out in a rather novel design of open berths. Because the berthing of Third Class was distributed at either end of the vessel, the forward compartments each had berths for roughly 100 men, whereas conventional open berth dormitories often berthed up to 300 passengers on other ships. This allowed for a more open layout which was far less crowded, complete with long tables and wooden benches where male passengers were served their meals.[10]

In the aft quarters of the ship for Third Class were accommodations for single women, married couples and families located in five compartments (parallel to the forward layout, with two on the Saloon deck and three on the Main deck). As was seen aboard Teutonic and Majestic, as well as the newly completed Cymric, there were a limited number of two-berth and four-berth cabins, these were strictly reserved for married couples and families with children. The smaller of the two Saloon deck compartments was designated for married couples. On the main deck, a section of another compartment was designated for families with children. Each of the two compartments also had small dining rooms fashioned with fitted tables and swivel chairs similar to that in Second Class. In the remaining three compartments, single women were berthed in 20-berth dormitory-style cabins situated on the outer sides of each compartment. At the centre of each compartment, a widened corridor was fashioned as a dining room with long fitted tables and swivel chairs running lengthwise through each compartment.[11][12]

Proposed sister ship Olympic

editAs White Star typically ordered ships in pairs, a sister ship for Oceanic to be named Olympic was proposed. However, following the death of the company chairman Thomas Ismay in November 1899, the order was postponed and then cancelled. Instead the company decided to deploy the resources to produce a set of larger liners which would become the "Big Four" class. The name Olympic was later bestowed upon the Olympic of 1910.[5][2]

Career

editOceanic was launched on 14 January 1899, an event watched by over 50,000 people. She would be the largest and last British liner to be launched in the 19th century. Following her fitting out and sea trials, she left Belfast for Liverpool on the 26 August that year, and when she arrived she was opened to the public and press where she was received with great fanfare. She departed Liverpool on her maiden voyage to New York on 6 September, under the command of Captain John G. Cameron. Thomas Ismay had planned to be on board but was by this stage too unwell. She completed the voyage in 6 days 2 hours and 37 minutes at an average speed of 19.57 knots (36.24 km/h; 22.52 mph) and arrived at New York to a rapturous welcome. One disappointing feature which soon became apparent in service was the tendency for the ship to experience excessive vibration at full speed, due in part to her long and narrow design. To avoid this problem it was soon found necessary to operate her at a service speed of 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h; 22.4 mph), lower than her planned service speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph).[2]

The early years of Oceanic's career were fairly eventful, as she was well received by the public on both sides of the Atlantic. Between 1900 and 1906, she bested her main rivals, Cunard's speed queens Campania and Lucania, as well as her own running mates for westbound crossings.[13]

In 1900, she was struck by lightning while at dock at Liverpool and lost the top of her mainmast. On 4 August that year while berthed at New York harbour, she was threatened by a serious fire in a cargo hold of the Bovic which was docked adjacent to her. The fire was brought under control before it could spread to Oceanic.[2] On 7 August 1901 in a heavy fog, near Tuskar Rock, Ireland, Oceanic was involved in a collision with the small Waterford Steamship Company Kincora, sinking the smaller vessel and killing seven.[6][2]

On 18 November 1904, four days out from New York, Oceanic encountered strong gales, stormy seas and snow, the battering the ship took from the sea stove in two portholes, which allowed a considerable amount of water to enter the ship.[2]

In 1905, 45 of the ship's firemen mutinied in protest at the unpleasant working conditions in the ship's boiler rooms, which resulted in the conviction and imprisonment of 33 stokers.[14][2]

In 1907, White Star set in place plans to establish an express service out of Southampton. Another IMM subsidiary, the American Line, had experienced great success out of this port due to its proximity to London, and it was ultimately decided Oceanic, along with Teutonic, Majestic and the newly completed Adriatic would terminate from this port, making double calls at the French port of Cherbourg and the line's traditional terminal at Queenstown before setting for New York.

In April 1912, during the departure of Titanic from Southampton, Oceanic became involved in the near collision of Titanic with SS New York, when Oceanic was nearby as New York broke from her mooring and nearly collided with Titanic, due to the large wake caused by Titanic's size and speed. A month later, in mid-May 1912, Oceanic picked up three bodies in one of the lifeboats left floating in the North Atlantic after Titanic sank. After their retrieval from Collapsible A by Oceanic, the bodies were buried at sea.[15]

World War I

editOceanic had been built under a deal with the Admiralty, which made an annual grant toward the maintenance of any ship on the condition that it could be called upon for naval work, during times of war. Such ships were built to particular naval specifications, in the case of Oceanic so that the 4.7-inch (120 mm) guns she was to be given could be quickly mounted. "The greatest liner of her day" was commissioned into Royal Navy service on 8 August 1914 as an armed merchant cruiser.[2]

On 25 August 1914, the newly designated HMS Oceanic departed Southampton on naval service that was to last just two weeks. Oceanic was to patrol the waters from the North Scottish mainland to the Faroes, in particular the area around Shetland. She was empowered to stop shipping at her captain's discretion, and to check cargoes and personnel for any potential German connections. For these duties, she carried Royal Marines and Captain William Slayter was appointed in command. Her former merchant master, Captain Henry Smith, with two years' service, remained in the ship with the rank of commander RNR. Many of the original crew also continued to serve on Oceanic. In effect therefore Oceanic had two captains, and this would lead to confusion about the chain of command.[2]

Wrecking

editOceanic headed for Scapa Flow in Orkney, Britain's main naval anchorage, with easy access to the North Sea and the Atlantic. From here she proceeded north to Shetland travelling continuously on a standard zigzag course as a precaution against being targeted by U-boats. This difficult manoeuvring required extremely accurate navigation, especially with such a large vessel. In the end it appears to have been poor navigation, rather than enemy action, that was to doom Oceanic.[2]

An inaccurate fix of their position was made on the night of 7 September by navigator Lieutenant David Blair. While everyone on the bridge thought they were well to the southwest of the Isle of Foula, they were in fact an estimated thirteen to fourteen miles (21 to 23 km) farther north than they believed and to the east of the island instead of the west. This put them directly on course for a reef, the notorious Shaalds of Foula (also known as the Hoevdi Grund and so marked on charts), which poses a major threat to shipping, coming within a few feet of the surface, and in calm weather giving no warning sign whatsoever.[2]

Captain Slayter had retired after his night watch, unaware of the situation, with orders to steer to Foula. Commander Smith took over the morning watch. Having previously disagreed with his naval superior about navigating a ship as large as Oceanic in the dangerous waters around the Scottish islands, he instructed the navigator to plot a course west, and out to sea, away (so he thought) from hidden dangers like outlying reefs. Unbeknown to Smith, this put the ship onto a course between the island and the reef just south of it. Slayter must have felt the course change, as he reappeared on the bridge to countermand Smith's order and made what turned out to be a hasty and ill-informed judgement, as the ship again changed course directly towards the reef.[2]

The ship ran aground on the Shaalds on the morning of 8 September, approximately 2.5 nautical miles (4.6 km; 2.9 mi) east of Foula's southern tip. She was wrecked in a flat calm and clear weather. She was the first Allied passenger ship to be lost in the war.[2] She lies at 60°07.05′N 001°58.30′W / 60.11750°N 1.97167°W, grid reference HU 01172 36937.[16]

Rescue

editThe Aberdeen trawler Glenogil was the first vessel on the scene, and although she attempted to pull off the massive ship, it proved an impossible task, and with the hull already ruptured, Oceanic would not have stayed afloat long in open waters.[17] Other ships in the area were called in to assist in the rescue operation that was to follow. All of the ship's crew transferred to the trawler via the ship's lifeboats and were then ferried to the waiting armed merchant cruiser HMS Alsatian, and HMS Forward. Charles Lightoller, the ship's First Officer (and also the most senior officer to survive the sinking of the Titanic), was the last man off, taking the navigation room's clock as a souvenir.

The 573-ton Admiralty salvage vessel Lyons was dispatched to the scene hurriedly, and in the words of the Laird of Foula, Professor Ian Holbourn, writing about the disaster in his book The Isle of Foula:

The launch of the Lyons, a salvage boat which hurried to the scene, was capable of a speed of ten knots, yet was unable to make any headway against the tide although she tried for fifteen minutes. Even then it was not the top of the tide, and the officer in charge reckoned the full tide would be 12 knots, he confessed he would not have believed it had he been told.[18]

Commander Smith is said to have come ashore at the remote island's tiny pier, and on looking back out to sea toward his stranded ship two miles away, commented that the ship would stay on the reef as a monument and nothing would move it. One of the Foula men, wise to the full power and fury of a Shetland storm, is said to have muttered with a cynicism not unknown in those parts "I‘ll give her two weeks".[18]

Remarkably, following a heavy gale that had persisted throughout the night of 29 September, just two weeks after the incident the islanders discovered the following day that the ship had been entirely swallowed up by the sea, where she remains to this day scattered as she fell apart under the pressure of the seas on the Shaalds.

The disaster was covered up at the time, since it was felt that it would have been embarrassing to make public how a world-famous liner had run aground in friendly waters in good weather within a fortnight of beginning its service as a naval vessel. The revelation of such gross incompetence at this early stage of the war would have done nothing for national morale.

Courts-martial

editLt. Blair was court-martialled at Devonport in November 1914, when he was found guilty of "stranding or suffering to be stranded" HMS Oceanic, and was ordered to be reprimanded. He offered in his defence that he was exonerated by the evidence given by Captain Slayter and Commander Smith that he was under their supervision, and that the stranding was due to abnormal currents.

A similar charge was made against Commander Smith at a second court-martial; the evidence for the prosecution was the same as in the previous case, but witnesses were cross-examined with a view to showing that the position of the accused on Oceanic was not clearly defined by the naval authorities, and that he was understood to be acting solely in an advisory capacity. He was acquitted the following day, as he was found not to have been in command on 8 September.

Captain Slayter was also acquitted.

Salvage

editIn 1924, a salvage company which had been engaged on the scuttled German warships at Scapa Flow attempted to salvage what remained of the wreck; however they were unsuccessful. In 1973 another attempt was made to salvage parts of the wreck and the propellers for scrap.[19] Over the next six years, Simon Martin and Alec Crawford, with wet-suits and Scuba gear, and initially working from an inflatable dinghy, recovered more than 200 tonnes of non-ferrous metal. Martin told the story in his best-selling book, The Other Titanic.[20]

Lifeboat

editIn 2016, Oceanic's Lifeboat 6 was rediscovered and subsequently restored.[21] It is in the collection of the Shetland Museum in Lerwick. The lifeboat is one of the last two White Star Line lifeboats still intact in the world, the other being Lifeboat 2 from SS Nomadic (1911).[22]

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "R.M.S. Oceanic (II)". Jeff Newman. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kerbrech, Richard De (2009). Ships of the White Star Line. Ian Allan Publishing. pp. 81–86. ISBN 978-0-7110-3366-5.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Bonsor, N.R.P. (1978). North Atlantic Seaway. pp. 739–40.

- ^ a b Haws, Duncan (1990). White Star Line (Oceanic Steam Navigation Company). TCL Publications. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-946378-16-9.

- ^ a b "RMS Oceanic". Darrel R. Hagberg. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

- ^ Lightoller, C.H. (1935). Titanic and other ships. I. Nicholson and Watson. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2008. republished as a Gutenberg of Australia eBook

- ^ Chirnside, Mark. 'Oceanic: White Star's Ship of the Century', p. 38-45

- ^ Technical Publishing Co Ltd (1899). The Practical Engineer. Vol. XX, July–December. Manchester: Technical Publishing Co Ltd. p. 214.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark. p. 48-49.

- ^ Chirnside Mark. p. 50.

- ^ 'The Titanic Commutator; Vol II, Issue 23, Fall 1979: p. 7, 9, 28, 33.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark. p. 76.

- ^ "Mutiny Aboard A White Star Line Ship". Titanic and Other White Star Line Ships. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2008.

- ^ Bartlett 2011, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "HMS Oceanic: Hoevdi Grund, Foula, Atlantic (102901)". Canmore. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Oceanic". The Great Ocean Liners. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ a b Holbourn, Ian Stoughton (2001). The Isle of Foula. Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 1-84158-161-5.

- ^ "Navy News" (628). United Kingdom Ministry of Defence. November 2006: 14. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Obituary: Simon Martin, journalist, businessman and wreck salvor". The Scotsman. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Oceanic lifeboat restoration almost complete". Shetland News. 2 April 2016. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Nomadic's Surviving Lifeboat". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

Bibliography

edit- Bartlett, W.B. (2011). Titanic: 9 Hours to Hell, the Survivors' Story. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-0482-4.

- Chirnside, Mark (2018). Oceanic: White Star's 'Ship of the Century'. Stroud, Glos: The History Press. ISBN 9780750985789.

- The Other Titanic, Simon Martin (Salvage report, 1980).

- Osborne, Richard; Spong, Harry & Grover, Tom (2007). Armed Merchant Cruisers 1878–1945. Windsor, UK: World Warship Society. ISBN 978-0-9543310-8-5.

External links

edit- Oceanic on thegreatoceanliners.com

- Oceanic - at the White Star Line History Website

- White Star Line Brochure 1907 contains photographs and accommodation descriptions for Oceanic and other White Star ships.

- YouTube video dedicated to the RMS Oceanic

- Scottish Shipwrecks, RMS Oceanic