A spinal nerve is a mixed nerve, which carries motor, sensory, and autonomic signals between the spinal cord and the body. In the human body there are 31 pairs of spinal nerves, one on each side of the vertebral column.[1][2] These are grouped into the corresponding cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral and coccygeal regions of the spine.[1] There are eight pairs of cervical nerves, twelve pairs of thoracic nerves, five pairs of lumbar nerves, five pairs of sacral nerves, and one pair of coccygeal nerves. The spinal nerves are part of the peripheral nervous system.[1]

| Spinal nerve | |

|---|---|

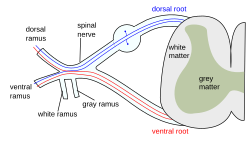

The formation of the spinal nerve from the posterior and anterior roots | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus spinalis |

| MeSH | D013127 |

| TA98 | A14.2.00.027 |

| TA2 | 6143 |

| FMA | 5858 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Structure

editEach spinal nerve is a mixed nerve, formed from the combination of nerve root fibers from its dorsal and ventral roots. The dorsal root is the afferent sensory root and carries sensory information to the brain. The ventral root is the efferent motor root and carries motor information from the brain. The spinal nerve emerges from the spinal column through an opening (intervertebral foramen) between adjacent vertebrae. This is true for all spinal nerves except for the first spinal nerve pair (C1), which emerges between the occipital bone and the atlas (the first vertebra).[3] Thus the cervical nerves are numbered by the vertebra below, except spinal nerve C8, which exists below vertebra C7 and above vertebra T1. The thoracic, lumbar, and sacral nerves are then numbered by the vertebra above. In the case of a lumbarized S1 vertebra (also known as L6) or a sacralized L5 vertebra, the nerves are typically still counted to L5 and the next nerve is S1.

1. Somatic efferent.

2. Somatic afferent.

3,4,5. Sympathetic efferent.

6,7. Autonomic afferent.

Outside the vertebral column, the nerve divides into branches. The dorsal ramus contains nerves that serve the posterior portions of the trunk carrying visceral motor, somatic motor, and somatic sensory information to and from the skin and muscles of the back (epaxial muscles). The ventral ramus contains nerves that serve the remaining anterior parts of the trunk and the upper and lower limbs (hypaxial muscles) carrying visceral motor, somatic motor, and sensory information to and from the ventrolateral body surface, structures in the body wall, and the limbs. The meningeal branches (recurrent meningeal or sinuvertebral nerves) branch from the spinal nerve and re-enter the intervertebral foramen to serve the ligaments, dura, blood vessels, intervertebral discs, facet joints, and periosteum of the vertebrae. The rami communicantes contain autonomic nerves that serve visceral functions carrying visceral motor and sensory information to and from the visceral organs.

Some anterior rami merge with adjacent anterior rami to form a nerve plexus, a network of interconnecting nerves. Nerves emerging from a plexus contain fibers from various spinal nerves, which are now carried together to some target location. The spinal plexuses are the cervical plexus, brachial plexus, lumbar plexus, the sacral plexus and the much smaller coccygeal plexus.[3]

Regional nerves

editCervical nerves

editThe cervical nerves are the spinal nerves from the cervical vertebrae in the cervical segment of the spinal cord. Although there are seven cervical vertebrae (C1–C7), there are eight cervical nerves C1–C8. C1–C7 emerge above their corresponding vertebrae, while C8 emerges below the C7 vertebra. Everywhere else in the spine, the nerve emerges below the vertebra with the same name.

The posterior distribution includes the suboccipital nerve (C1), the greater occipital nerve (C2) and the third occipital nerve (C3). The anterior distribution includes the cervical plexus (C1–C4) and brachial plexus (C5–T1).

The cervical nerves innervate the sternohyoid, sternothyroid and omohyoid muscles.

A loop of nerves called ansa cervicalis is part of the cervical plexus.

Thoracic nerves

editThe thoracic nerves are the twelve spinal nerves emerging from the thoracic vertebrae. Each thoracic nerve T1–T12 originates from below each corresponding thoracic vertebra. Branches also exit the spine and go directly to the paravertebral ganglia of the autonomic nervous system where they are involved in the functions of organs and glands in the head, neck, thorax and abdomen.

Anterior divisions

editThe intercostal nerves come from thoracic nerves T1–T11, and run between the ribs. At T2 and T3, further branches form the intercostobrachial nerve. The subcostal nerve comes from nerve T12, and runs below the twelfth rib.

Posterior divisions

editThe medial branches (ramus medialis) of the posterior branches of the upper six thoracic nerves run between the semispinalis dorsi and multifidus, which they supply; they then pierce the rhomboid and trapezius muscles, and reach the skin by the sides of the spinous processes. This sensitive branch is called the medial cutaneous ramus.

The medial branches of the lower six are distributed chiefly to the multifidus and longissimus dorsi, occasionally they give off filaments to the skin near the middle line. This sensitive branch is called the posterior cutaneous ramus.

Lumbar nerves

editThe lumbar nerves are the five spinal nerves emerging from the lumbar vertebrae. They are divided into posterior and anterior divisions.

Posterior divisions

editThe medial branches of the posterior divisions of the lumbar nerves run close to the articular processes of the vertebrae and end in the multifidus muscle.

The laterals supply the erector spinae muscles.

The upper three give off cutaneous nerves which pierce the aponeurosis of the latissimus dorsi at the lateral border of the erector spinae muscles, and descend across the posterior part of the iliac crest to the skin of the buttock, some of their twigs running as far as the level of the greater trochanter.

Anterior divisions

editThe anterior divisions of the lumbar nerves (rami anteriores) increase in size from above downward. They are joined, near their origins, by gray rami communicantes from the lumbar ganglia of the sympathetic trunk. These rami consist of long, slender branches which accompany the lumbar arteries around the sides of the vertebral bodies, beneath the psoas major. Their arrangement is somewhat irregular: one ganglion may give rami to two lumbar nerves, or one lumbar nerve may receive rami from two ganglia.

The first and second, and sometimes the third and fourth lumbar nerves are each connected with the lumbar part of the sympathetic trunk by a white ramus communicans.

The nerves pass obliquely outward behind the psoas major, or between its fasciculi, distributing filaments to it and the quadratus lumborum.

The first three and the greater part of the fourth are connected together in this situation by anastomotic loops, and form the lumbar plexus.

The smaller part of the fourth joins with the fifth to form the lumbosacral trunk, which assists in the formation of the sacral plexus. The fourth nerve is named the furcal nerve, from the fact that it is subdivided between the two plexuses.

Sacral nerves

editThe sacral nerves are the five pairs of spinal nerves which exit the sacrum at the lower end of the vertebral column. The roots of these nerves begin inside the vertebral column at the level of the L1 vertebra, where the cauda equina begins, and then descend into the sacrum.[4][5]

There are five paired sacral nerves, half of them arising through the sacrum on the left side and the other half on the right side. Each nerve emerges in two divisions: one division through the anterior sacral foramina and the other division through the posterior sacral foramina.[4]

The nerves divide into branches and the branches from different nerves join with one another, some of them also joining with lumbar or coccygeal nerve branches. These anastomoses of nerves form the sacral plexus and the lumbosacral plexus. The branches of these plexus give rise to nerves that supply much of the hip, thigh, leg and foot.[4][6]

The sacral nerves have both afferent and efferent fibers, thus they are responsible for part of the sensory perception and the movements of the lower extremities of the human body. From the S2, S3 and S4 arise the pudendal nerve and parasympathetic fibers whose electrical potential supply the descending colon and rectum, urinary bladder and genital organs. These pathways have both afferent and efferent fibers and, this way, they are responsible for conduction of sensory information from these pelvic organs to the central nervous system (CNS) and motor impulses from the CNS to the pelvis that control the movements of these pelvic organs.[6]

Coccygeal nerves

editThe bilateral coccygeal nerves, Co, are the 31st pair of spinal nerves. It arises from the conus medullaris, and its ventral ramus helps form the coccygeal plexus. It does not divide into a medial and lateral branch. Its fibers are distributed to the skin superficial and posterior to the coccyx bone via the anococcygeal nerve of the coccygeal nerve plexus.

Function

edit| Level | Motor function |

|---|---|

| C1–C6 | Neck flexors |

| C1–T1 | Neck extensors |

| C3, C4, C5 | Supply diaphragm (mostly C4) |

| C5, C6 | Move shoulder, raise arm (deltoid); flex elbow (biceps) |

| C6 | externally rotate (supinate) the arm |

| C6, C7 | Extend elbow and wrist (triceps and wrist extensors); pronate wrist |

| C7, C8 | Flex wrist; supply small muscles of the hand |

| T1–T6 | Intercostals and trunk above the waist |

| T7–L1 | Abdominal muscles |

| L1–L4 | Flex hip joint |

| L2, L3, L4 | Adduct thigh; Extend leg at the knee (quadriceps femoris) |

| L4, L5, S1 | abduct thigh; Flex leg at the knee (hamstrings); Dorsiflex foot (tibialis anterior); Extend toes |

| L5, S1, S2 | Extend leg at the hip (gluteus maximus); flex foot and flex toes |

Spinal plexuses

editA spinal plexus is a weblike nerve plexus formed by the anterior nerve roots that branch and merge repeatedly. The only region that does not have a plexus is the thoracic region. The small cervical plexus is in the neck, the brachial plexus is in the shoulder, the lumbar plexus is in the lower back, beneath this is the sacral plexus, and next to the lower sacrum and coccyx is the very small coccygeal plexus.[3]

Clinical significance

editThe muscles that one particular spinal root supplies are that nerve's myotome, and the dermatomes are the areas of sensory innervation on the skin for each spinal nerve. Lesions of one or more nerve roots result in typical patterns of neurologic defects (muscle weakness, abnormal sensation, changes in reflexes) that allow localization of the responsible lesion.

There are several procedures used in sacral nerve stimulation for the treatment of various related disorders.

Sciatica is generally caused by the compression of lumbar nerves L4, or L5 or sacral nerves S1, S2, or S3, or by compression of the sciatic nerve itself

Additional Images

edit-

A portion of the spinal cord, showing its right lateral surface. The dura is opened and arranged to show the nerve roots.

-

Distribution of the cutaneous nerves. Ventral aspect.

-

Distribution of the cutaneous nerves. Dorsal aspect.

-

The spinal cord with dura cut open, showing the exits of the spinal nerves.

-

The spinal cord showing how the anterior and posterior roots join in the spinal nerves.

-

A longer view of the spinal cord.

-

Projections of the spinal cord into the nerves (red motor, blue sensory).

-

Projections of the spinal cord into the nerves (red motor, blue sensory).

-

Schematic diagram of cervical plexus.

- Dissection images

-

Cerebrum. Inferior view. Deep dissection.

-

Cerebrum. Inferior view. Deep dissection.

-

Spinal nerves. Spinal cord and vertebral canal. Deep dissection.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Kaiser, JT; Lugo-Pico, JG (January 2024). Neuroanatomy, Spinal Nerves. PMID 31194375.

- ^ "A Neurosurgeon's Overview of the Anatomy of the Spine and Peripheral Nervous System". www.aans.org. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 382–388. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ a b c 1. Anatomy, descriptive and surgical: Gray's anatomy. Gray, Henry. Philadelphia : Courage Books/Running Press, 1974

- ^ 2. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Moore, Keith L. Philadelphia : Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010 (6th ed)

- ^ a b 3. Human Neuroanatomy. Carpenter, Malcolm B. Baltimore : Williams & Wilkins Co., 1976 (7th ed)

- Blumenfeld H. 'Neuroanatomy Through Clinical Cases'. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 2002.

- Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. 'Gray's Anatomy for Students'. New York: Elsevier; 2005:69-70.

- Ropper AH, Samuels MA. 'Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology'. Ninth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill; 2009.