The Sacramento Union was a daily newspaper founded in 1851 in Sacramento, California. It was the oldest daily newspaper west of the Mississippi River before it closed its doors after 143 years in January 1994, no longer able to compete with The Sacramento Bee, which was founded in 1857, just six years after the Union.

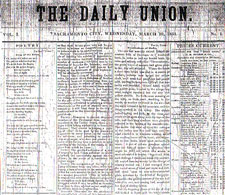

The March 19, 1851 front page of the first edition of The Sacramento Union | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Owner(s) | Various |

| Publisher | Various |

| Editor | Various |

| Founded | 1851 |

| Ceased publication | 1994 |

| Headquarters | 301 Capitol Mall Sacramento, CA 95814 |

| Circulation | 105,000 (at max) |

| Website | none |

Founding

editThe birth of this storied newspaper institution began in 1851 when the city of Sacramento was in its infancy.

Under the direction of its first editor, Dr. John F. Morse, who had attracted proprietors through letters to the New Orleans Delta and well-known literary attainments, The Union was initially printed as The Daily Union on Wednesday, March 19, 1851. Upon the front page of this 23-inch by 34-inch paper, Morse addressed the readers of The Union, committing to “publish the first news in the best style and at the lowest prices” and “to have an efficient correspondent in every important town and mining region in the state.”

The paper had evolved through the efforts of four Sacramento Transcript printers. The printers had introduced the idea of The Union's creation a year earlier, due to their frustrations with a labor dispute between the Transcript and the Placer Times, which were the city's first two newspapers. The battle between these two newspapers became so fierce that the papers sold advertising space for below the cost of composition for the mere purpose of undercutting their competition.

Opening its operation at its 21 J St. headquarters, The Union endured very competitive times during its early years, when it was one of about 60 Sacramento newspapers.

Sacramento's status as a newspaper town, however, was short-lived, as all but two newspapers failed, leading to the Union's famous slogan, “The Oldest Daily in the West”. The Union's early years are also recognized for their famous contributors, who included Mark Twain, Bret Harte and Dan De Quille.

The Daily Union evolved quite quickly as a leading newspaper, as its initial circulation of 500 was soon afterward expanded with an even wider circulation and the daily publication was joined by the semi-monthly Steamer Union (1851) for Atlantic states and European readers, the Weekly Union (1852), and the semi-annual Pictorial Union (1853), which featured drawings of towns, landscapes and other scenes of the era.

The Union, which was often referred to as the “Miners’ Bible” during its early years, passed a major test when it overcame a great fire on November 2, 1852, and continued printing on a small press that was saved from the flames. A brick building, which still stands today, was later constructed at 121 J Street to replace the paper's original building, a California Historical Landmark No. 605. [2]

In 1852, Thomas Gardiner, one of the founders of the Los Angeles Times, was publisher of the Union.[3]

On November 17, 1858, The Union became the first California newspaper to issue a double-sheet daily. The publication was also recognized as the largest double-sheet daily in the nation.

The Sacramento Publishing Co. purchased the Sacramento Daily Union, as it was then known, and the Daily Record in 1875, and merged them into one newspaper, calling it the Sacramento Daily Record-Union – a name that was later dropped.

Mark Twain and The Sacramento Union

editThe Missouri-born Samuel Langhorne Clemens, who is better known by his pen name of Mark Twain, is remembered most for his contributions to The Union. This point was evident through the large bronze bust of Twain, which sat just west of the State Capitol in the lobby of The Union’s latter building at 301 Capitol Mall.

Inscribed on the bust were Twain’s words: “Early in 1866, George Barnes invited me to resign my reportership on his paper, the San Francisco Morning Call, and for some months thereafter, I was without money or work; then I had a pleasant turn of fortune. The proprietors of the Sacramento Union, a great and influential daily journal, sent me to the Sandwich Islands to write four letters a month at twenty dollars a piece. I was there for four or five months, and returned to find myself about the best known man on the Pacific Coast.”

Twain dispatched a series of articles on Hawaii for The Union in 1866. These were very popular, and many historians credit the series with turning Twain into a journalistic star. Because many people thought that Twain wrote in The Union building, whenever The Union was struggling financially during the turn of the 20th century, the owners would drag out an old desk and sell it for a princely sum as "the desk where Mark Twain sat."

Unfortunately, said Charlotte Gilmore, former head of The Union's “morgue” or bound volumes collection, the original Twain articles were cut out and stolen from The Union's bound volumes during the 1970s.

“Sometime after I left in the summer of 1971, it happened,” Gilmore said. “It’s a very disappointing situation, but at least the (Twain) articles were photographed (for microfilm) before this happened.”

The Union's bound volumes, as well as the bronze bust of Twain, are now in the possession of the Shields Library at UC Davis, having been donated by the Danel and Reboin families, owners of the Herald Printing Co. The Twain articles can be viewed on microfilm at the Sacramento Public Library's central location at 828 I St.

Late 20th century

editIn 1966, the paper was purchased by Copley Press, which brought in millions of dollars that resulted in improvements such as the 1967 construction of the publication's Capitol Mall headquarters and a new long-run, photo-offset press. During those years it was the dominant morning newspaper in Sacramento. Then, in the mid-1970s, the Bee, previously an afternoon newspaper, decided to go head-to-head with the Union as a morning newspaper and promised that the Bee would arrive on the doorstep by 6:00 a.m. The Union circulation department couldn't equal that service, and the Bee quickly became the larger of the two dailies. While the Bee had a much larger staff, the Union beat the Bee on a number of huge stories. Among them were the Dorothea Puente Victorian grave sites and the investigative reporting that led to the resignation of California Department of Education Superintendent Bill Honig.

Copley sold the Union to conservative financier Richard Mellon Scaife in 1977. While there were reports that Scaife lost millions of dollars every year on the newspaper, he enjoyed having a conservative voice in the capital of the largest liberal state in the union. In the late 1980s, the newspaper changed from the standard broadsheet size to a tabloid, and the Union launched a marketing campaign called "Grab the Tab." For the most part, it was a failure and the paper suffered losses in circulation.

In 1989, Scaife sold the Union to local real estate developers Daniel Benvenuti Jr. and David Kassis. They hired Joseph Farah as editor. Under Farah's editorship, the paper veered even further to the right and became, in the words of a former Union journalist, "a mouthpiece for the fundamentalist Christian right, preoccupied with abortion, homosexuals and creationism."[4] Benvenuti and Kassis sold the newspaper's press in 1991 to a Mexican town and had the paper printed at Herald Printing.[citation needed] In 1992, Herald's president Ralph Danel Jr. acquired the Union from Benvenuti and Kassis in November 1992; the selling price was in large part the debt that Benvenuti and Kassis owed Herald for its printing services.[citation needed]

The newspaper in 1991 and 1992 ran a series of investigative reports that revealed that then-state Superintendent of Public Instruction Bill Honig had directed state education officials to contract with a company run by his wife, Nancy, out of their San Francisco home, that was designed to get parents more involved in their children's education. At Honig's direction, state funds were ultimately used to pay employees of Nancy Honig's company, the Quality Education Project (QEP). Bill Honig was later indicted and convicted on conflict-of-interest charges, although the felonies were later reduced to misdemeanors. Honig, who had been rumored to be a candidate for California governor, attributed the investigation to Republicans who didn't want him to win higher office.

In an attempt to reduce losses, circulation was dropped outside of the Sacramento metro area and, two months before its closure, publication was changed from seven days a week to three days a week. The formerly daily Union published its final edition on Friday, January 14, 1994. The cover featured a color photo of the paper's last staff under the blaring headline, "We're History," coined by the newspaper's last editor, Ken Harvey.

Revival attempts

edit2005: Sacramento Union Magazine

edit| Type | Alternative weekly |

|---|---|

| Format | Tabloid |

| Owner(s) | The Sacramento Union, LLC |

| Publisher | J.C. Dutra |

| Editor | J.C. Dutra |

| Managing editor | Bruce Edgar Slaton Jr |

| Founded | 2006 |

| Language | English |

| Ceased publication | 2009 |

| Headquarters | PO Box 748 Sacramento, CA 95812 United States |

| Circulation | 62,000 |

| Website | www.TheSacramentoUnion.com [1] |

The road to the rebirth of The Union in its newspaper form began in early 2004, when the name of the newspaper was acquired for the purpose of restarting the publication.

To meet its goals, the new Union set up offices in Fair Oaks and worked with former Union publishing staff to prepare for its return.

In August 2004, a modernized Sacramento Union returned with bimonthly magazines, then started publishing monthly in May 2005. James H. Smith, a former publisher of the Sacramento Union newspaper and co-founder of the Western Journalism Center with Farah, served as publisher, and Kenneth E. Grubbs Jr., former director of the National Journalism Center who had also worked for the Orange County Register, served as editor.

The publishers did not intend to return as a print daily newspaper, concentrating instead on web and magazine publishing.

Due to its very limited success, the magazine ceased existing after only five issues. Much of the office staff was laid off in May 2005.[5]

Ryan Rose, The Union's current managing editor, served as the magazine's Web editor; he said that many people were confused upon seeing The Union as a magazine.

“We were known in this region for more than 100 years as a newspaper and then less than 10 years after The Union closed as a newspaper, we reissued it as a magazine and I firmly believe that the magazine suffered because we betrayed the brand,” Rose said.

After several months of dormancy, a new print edition of The Sacramento Union appeared on Friday, July 21, 2006, sporting a similar masthead as the magazine and the notation "Since 1851". The volume number in the paper was listed as "Volume 1, Number 1."

2006-2009: Tabloid

editIn 2006, The Sacramento Union was reborn as a tabloid-sized free weekly newspaper from 2006 to 2009. Published by the Sacramento Union, LLC, the paper also published a daily news website. J.C. Dutra was The Union's publisher and editor-in-chief. The paper was conservative in tone.

The Sacramento Union suspended publication of both the paper and the website in March 2009.[6]

The Sacramento Union was acquired along with 45 other newspapers across the United States by a holding company controlled by Bruce Edgar Slaton Jr. for an undisclosed price.[citation needed]

Newspaper building

editIn the autumn of 2005, demolition crews razed the old daily Union office building, located at 301 Capitol Mall in downtown Sacramento. The building was constructed in 1967. (Earth Metrics Inc., 1989.) A 53-story high-rise called "The Towers on Capitol Mall" was planned for the Union's previous spot, but by 2007, the developer was struggling to finance the project and plans were scrapped. The former location is currently fenced off and its future is unknown.

Archives

editThe archives of the daily Union are in the Special Collections of the Shields Library of UC Davis. California Digital Newspaper Collection has in its on-line archives the Sacramento Daily Union (Sacramento, 1851–1899). Sacramento Public Library's holdings contain complete microfilm archives of The Sacramento Union from 1851 (founding) to January 1994 (when publication ceased) and are located at its Central Library.

References

edit- ^ O'Day, E. Clarence (August 1920). "Stories From The Files-Narrative Which Unexpectedly Made Bret Harte a Literary Celebrity". Overland Monthly. LXXV (2).

- ^ "The Sacramento Union #605". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ^ "San Diego County," Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1899, page A-7 Access to this link may require the use of a library card.

- ^ Intelligence Files: Joseph Farah, Southern Poverty Law Center, retrieved 4 August 2013

- ^ Larson, Mark (2005-05-29). "Glossy version of Union sacks most of staff". American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on 2008-06-27.

- ^ ""Sacramento Union" Newspaper Dead at 143". KNBC. 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2024-10-06.

- Environmental Site Assessment for the Sacramento Union Building, 301 Capitol Building, Sacramento, Ca., Earth Metrics Inc., November 22, 1989

- Elisabeth Sherwin (2000). The Sacramento Union rests in peace at Shields. Retrieved January 25, 2006.

- Salamone, Kathleen. Seceding from the Union: Kathleen Katanaka's explanation of why she left the "Sacramento Union." (Columbia Journalism Review, January/February 1991)

- Farah, Joseph. Why the Liberal Press Is Out to Get Us." (Columbia Journalism Review, January/February 1991). A rebuttal of Salamon's article.

- "Sacramento Union shifts from six to three days a week," Editor & Publisher, October 30, 1993.

- "Union's New Owner Plans to Turn Newspaper Around," The Business Journal-Sacramento, November 9, 1992.

- "One of West's Oldest Newspapers Shutting Down," Associated Press, January 12, 1994.

External links

edit- Sacramento Union Newspaper Archives at Special Collections Dept., University Library, University of California, Davis

- Sacramento Union archives, Sacramento Public Library