The Pacific white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens), also known as the hookfin porpoise, is an active dolphin found in the cool or temperate waters of the North Pacific Ocean.[4][5]

| Pacific white-sided dolphin[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

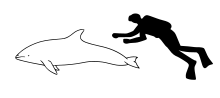

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Lagenorhynchus |

| Species: | L. obliquidens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lagenorhynchus obliquidens (Gill, 1865)

| |

| |

| Pacific white-sided dolphin range | |

Taxonomy

editThe Pacific white-sided dolphin was named by Smithsonian mammalogist Theodore Nicholas Gill in 1865. It is morphologically similar to the dusky dolphin, which is found in the South Pacific.[6] Genetic analysis by Frank Cipriano suggests the two species diverged around two million years ago.

Though traditionally placed in the genus Lagenorhynchus, molecular analyses indicate they are closer to dolphins of the genus Cephalorhynchus, in the Lissodelphininae subfamily, than to both the Atlantic white-sided dolphin and the White-beaked dolphin. It has therefore been proposed to move the Pacific white-sided dolphin to the resurrected genus Sagmatias together with other southern hemisphere Lagenorhyncus species (hourglass dolphin, Dusky dolphin and Peale's dolphin).[7] However, the detailed phylogenetic relationships within this group of dolphins is still not fully elucidated.

Description

editThe Pacific white-sided dolphin has three colors. The chin, throat and belly are creamy white. The beak, flippers, back, and dorsal fin are a dark gray. Light gray patches are seen on the sides and a further light gray stripe runs from above the eye to below the dorsal fin, where it thickens along the tail stock. A dark gray ring surrounds the eyes.

The species is an average-sized oceanic dolphin. Females weigh up to 150 kg (330 lb) and males 200 kg (440 lb) with males reaching 2.5 m (8.2 ft) and females 2.3 m (7.5 ft) in length. Pacific white-sided dolphins usually tend to be larger than dusky dolphins. Females reach maturity at seven years. From 1990 to 1991, a study conducted by Richard C. Ferrero and William A. Walker revealed the vast majority of Pacific white-sided dolphins that fell victim to the drift nets were between the ages of 8.3 to 11 when they sexually matured.[8] The gestation period usually last for one year. Individuals are believed to live up 40 years or more.[6]

The Pacific white-sided dolphin is extremely active and mixes with many of the other North Pacific cetacean species. It readily approaches boats and bow-rides. Large groups are common, averaging 90 individuals, with supergroups of more than 300. Prey includes mainly hake, anchovies, squid, herring, salmon, and cod.[9]

They have an average of 60 teeth.[10]

Range and habitat

editThe range of the Pacific white-sided dolphin arcs across the cool to temperate waters of the North Pacific.[6][11][12] Sightings go no further south than the South China Sea on the western side and the Baja California Peninsula on the eastern. Populations may also be found in the Sea of Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk. In the northern part of the range, some individuals may be found in the Bering Sea. The dolphins appear to follow some sort of migratory pattern – on the eastern side they are most abundant in the Southern California Bight in winter, but further north (Oregon, Washington) in summer. Their preference for off-shore deep waters appears to be year-round.[13][14] The only known predator of the Pacific white-sided dolphin is the killer whale,[15] but at least one case of predation by the great white shark has been recorded.[16]

The total population may be as many as 1 million.[6] However, the tendency of Pacific white-sided dolphins to approach boats complicates precise estimates via sampling.

Behavior

editThese dolphins keep close company.[17] White-sided dolphins swim in groups of 10 to 100, and can often be seen bow-riding and doing somersaults.[6][18] Members form a close-knit group and will often care for a sick or injured dolphin. Animals that live in such large social groups develop ways to keep in touch, with each dolphin identifying itself by a unique name-whistle. Young dolphins communicate with a touch of a flipper as they swim beside adults.

Studies conducted on Pacific white-sided dolphins, as well as Risso's dolphin have revealed a multitude of things about how they communicate as a species, which was revealed to be vastly different from bottlenose dolphins and common dolphins.[19] The studies have revealed that their notches and spectral peaks happen to be more low pitched when juxtaposed with the bottlenose dolphins and common dolphins as mentioned earlier.[20] Other studies have revealed similar behaviors. Two studies conducted back in 2010 and 2011 revealed that the vocalizations of Pacific white-sided dolphins can range differently only from their behavioral states, indicating strong similarities between the acoustic and surface behavior for various foraging behaviors, including the possibility of an undescribed subspecies. The oceanographical data in the area can also effect the behavioral patterns of the dolphins. The studies also revealed that the different types of echolocations do vary based on the geographical locations; the first population of Pacific white-sided dolphins that were observed, inhabiting the waters near the Pacific United States seemed to more activity during the night while the second population of Pacific white-sided dolphins, that were also observed, inhabiting areas near Baja California, were observed to be more active during the day, possibly due the seasons and the dolphins' search for prey.[21][22]

The first sighting of the species on Commander Islands involved a single dolphin to travel along with a pod of killer whales in 2013.[23]

Pacific white-sided dolphins are known to sleep on average seven hours a night.[24]

Relation to humans

editRight: Pacific white-sided dolphin named Spinnaker at Vancouver Aquarium

Protection

editUntil the United Nations banned certain types of large fishing nets in 1933, many Pacific white-sided dolphins were killed in drift nets. Some animals are still killed each year by Japanese hunting drives.

Captivity

editAlthough overshadowed in popularity by bottlenose dolphins, Pacific white-sided dolphins are also a part of some marine theme park shows. Roughly 100 reside in dolphinaria in North America and Japan. In captivity, they tend to consume less amounts of food when compared to their wild counterparts, this could be the case due to the fact of temperatures changing in the water based on the seasons. However, the condition in which the dolphins lives, most likely in an aquarium tank, will impact how much energy is required for a captive dolphin to thrive in captivity. Studies have also shown that the highest amount of food intake that a captive Pacific white-sided dolphin displays in autumn when the dolphin increase their food intake as well as their body mass.[25][26]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Ashe, E.; Braulik, G. (2018). "Lagenorhynchus obliquidens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T11145A50361866. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T11145A50361866.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Archived from the original on 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ "Pacific White-Sided Dolphin". NOAA Fisheries. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 19 October 2021. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ "Kenai Fjords National Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Wursig, Bernd; Perrin, William F.; Thewissen, J. 'Hans' (2009-02-26). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 817–818. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5. Archived from the original on 2021-12-27. Retrieved 2021-12-27.

- ^ Vollmer, Nicole L.; et al. (January 31, 2019). "Taxonomic revision of the dolphin genus Lagenorhynchus". Marine Mammal Science. 35 (3): 957–1057. Bibcode:2019MMamS..35..957V. doi:10.1111/mms.12573. S2CID 92421374. Archived from the original on 2021-11-11. Retrieved 2021-09-17.

- ^ Ferrero, R.C.; Walker, W.A. (1996). "Age, growth, and reproductive patterns of the Pacific white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens) taken in high seas drift nets in the central North Pacific Ocean". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 74 (9): 1673–1687. Bibcode:1996CaJZ...74.1673F. doi:10.1139/z96-185.

- ^ Morton, A. (January 2000). "Occurrence, Photo-identification and Prey of Pacific White-sided Dolphins (Lagenorhyncus obliquidens) in the Broughton Archipelago, Canada 1984–1998". Marine Mammal Science. 16 (1): 80–93. Bibcode:2000MMamS..16...80M. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2000.tb00905.x.

- ^ Black, Nancy A. (2009). Perrin, William F.; Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (2nd ed.). Burlington Ma.: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9. Archived from the original on 2009-11-09.

- ^ Salvadeo, CJ; Lluch-Belda, D; Gómez-Gallardo, A; Urbán-Ramírez, J; MacLeod, CD (2010-03-10). "Climate change and a poleward shift in the distribution of the Pacific white-sided dolphin in the northeastern Pacific". Endangered Species Research. 11: 13–19. doi:10.3354/esr00252. ISSN 1863-5407.

- ^ "PACIFIC WHITE-SIDED DOLPHIN (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens): North Pacific Stock" (PDF). NOAA Fisheries: 127–130. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-03. Retrieved 2022-12-31 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Black, N.A. (1994). Behavior and ecology of Pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens) in Monterey Bay, California. San Francisco State University.

- ^ Walker, W.A.; Leatherwood, S.; Goodrich, K.R.; Perrin, W.F.; Stroud, R.K. (1986). "Geographical variation and biology of the Pacific white-sided dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obliquidens, in the north-eastern Pacific". Research on Dolphins. 441: 465.

- ^ Dahlheim, M.E.; Towell, R.G. (1994). "Occurrence and Distribution of Pacific White-Sided Dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens) in Southeastern Alaska, With Notes On an Attack by Killer Whales (Orcinus orca)". Marine Mammal Science. 10 (4): 458–464. Bibcode:1994MMamS..10..458D. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1994.tb00501.x. Archived from the original on 2020-09-25. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- ^ Peter Klimley, A.; Ainley, David G. (3 April 1998). Great White Sharks: The Biology of Carcharodon carcharias. Academic Press. ISBN 9780080532608. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Cooperation among Adult Dolphins | Journal of Mammalogy | Oxford Academic". academic.oup.com. Archived from the original on 2022-12-31. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- ^ "Unusual Leap by a Pacific White-Sided Dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens) | Journal of Mammalogy | Oxford Academic". academic.oup.com. Archived from the original on 2022-12-31. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- ^ Henderson, E. Elizabeth; Hildebrand, John A.; Smith, Michael H. (July 2011). "Classification of behavior using vocalizations of Pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens)". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 130 (1): 557–567. Bibcode:2011ASAJ..130..557H. doi:10.1121/1.3592213. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 21786921. Archived from the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- ^ Soldevilla, M.S.; Henderson, E.E.; Campbell, G.S.; Wiggins, S.M.; Hildebrand, J.A.; Roch, M.A. (2008). "Classification of Risso's and pacific white-sided dolphins using spectral properties of echolocation clicks". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 124 (1): 609–24. Bibcode:2008ASAJ..124..609S. doi:10.1121/1.2932059. PMID 18647003. S2CID 14685920. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- ^ Henderson, E.E.; Hildebrand, J.A.; Smith, M.H. (2011). "Classification of behavior using vocalizations of pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens)". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 130 (1): 557–67. Bibcode:2011ASAJ..130..557H. doi:10.1121/1.3592213. PMID 21786921.

- ^ Soldevilla, M.S.; Wiggins, S.M.; Hildebrand, J.A. (2010). "Spatio-temporal comparison of pacific white-sided dolphin echolocation click types". Aquatic Biology. 9: 49–62. doi:10.3354/ab00224.

- ^ Commander Islands Nature and Biosphere Reserve. Тихоокеанский белобокий дельфин Sagmatias obliquidens Gill, 1865 Archived 2017-08-23 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on August 24, 2017

- ^ Goley, Patricia Dawn (October 1999). "Behavioral Aspects of Sleep in Pacific White-Sided Dolphins (Lagenorhynchus Obliquidens, Gill 1865)1". Marine Mammal Science. 15 (4): 1054–1064. Bibcode:1999MMamS..15.1054G. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00877.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ Piercey, R. (2013). "Seasonal changes in the food intake of captive Pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens)". Aquatic Mammals. 39 (3): 211–220. doi:10.1578/am.39.3.2013.211.

- ^ "Seasonal Resting Metabolic Rate and Food Intake of Captive Pacific White-Sided Dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens)". Archived from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- van Waerebeek, Koen; Würsig, Bernd (2002-02-05). "Pacific White-sided Dolphin and Dusky Dolphin". In Perrin, William R; Wiirsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J G M (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Gulf Professional. pp. 859–60. ISBN 978-0-12-551340-1.

- National Audubon Society: Guide to Marine Mammals of the World ISBN 0-375-41141-0

External links

edit- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society

- Voices in the Sea - Sounds of the Pacific white-sided Dolphin

- Photos of Pacific white-sided dolphin on Sealife Collection