The Cathedral Church and Minor Basilica of the Immaculate Mother of God, Help of Christians, Patroness of Australia (colloquially, St Mary's Cathedral) is the cathedral church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney and the seat of the Archbishop of Sydney, currently Anthony Fisher OP. It is dedicated to the "Immaculate Mother of God, Help of Christians", Patroness of Australia and holds the title and dignity of a minor basilica, bestowed upon it by Pope Pius XI on 4 August 1932.[2]

| St Mary's Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church and Minor Basilica of the Immaculate Mother of God, Help of Christians, Patroness of Australia | |

| St Mary's Basilica | |

St Mary's Cathedral at night | |

| 33°52′16″S 151°12′48″E / 33.87111°S 151.21333°E | |

| Location | Sydney, New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | stmaryscathedral |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | St Mary's Chapel |

| Status | Minor basilica (since 1932) Cathedral (since 1835) Chapel (1821–1835) National shrine[1] |

| Founded | 21 October 1821 |

| Dedication | Immaculate Conception, Mary Help of Christians |

| Dedicated | 29 June 1865 |

| Consecrated | 8 September 1882 |

| Relics held | First class relic of St Francis Xavier displayed, various others privately held |

| Events | Ruined by fire (29 June 1865) |

| Past bishop(s) | George Pell, Edward Clancy, John Bede Polding |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Architectural type | Chapel (first building) Cathedral (present building) |

| Style | Geometric Decorated Gothic |

| Years built | 1851 (first cathedral) 1928 (nave completed) 2000 (spires added) |

| Groundbreaking | 1821 (St Mary's Chapel) 1868 (present-day cathedral) |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 107 metres (351 ft) |

| Nave width | 24.3 metres (80 ft) |

| Nave height | 22.5 metres (74 ft) |

| Number of spires | 2 |

| Spire height | 74.6 metres (245 ft) |

| Materials | Sydney sandstone, Oamaru stone, marble, alabaster, Moruya granite |

| Bells | 14 |

| Tenor bell weight | 34 long cwt 1 qr 3 lb (3,839 lb or 1,741 kg) |

| Administration | |

| Province | Sydney |

| Metropolis | Sydney |

| Archdiocese | Metropolitan Archdiocese of Sydney |

| Deanery | City Deanery |

| Parish | St Mary's |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Anthony Fisher OP |

| Auxiliary Bishop(s) | Terence Brady, Richard Umbers, Danny Meagher |

| Dean | Donald Richardson |

| Chancellor | Chris Meney (Lay Chancellor) |

| Assistant priest(s) | Brendan Purcell, Emmanuel Lubega, Lewi Barakat |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Daniel Justin |

| Organist(s) | Simon Niemiński (Assistant Director of Music) |

| Servers' guild | Archconfraternity of St. Stephen |

| Official name | St. Mary's Catholic Cathedral and Chapter House; Saint Mary's Cathedral; St Marys Cathedral |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 3 September 2004 |

| Reference no. | 1709 |

| Type | Cathedral |

| Category | Religion |

| Builders | Jacob Inder (Chapter House) |

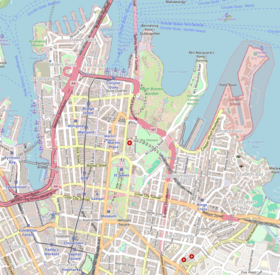

St Mary's has the greatest length of any church in Australia. It is located on College Street near the eastern border of the Sydney central business district in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. Despite the high-rise development of the central business district, the cathedral's imposing structure and twin spires make it a landmark from every direction. In 2008, St Mary's Cathedral became the focus of World Youth Day 2008 and was visited by Pope Benedict XVI who consecrated the new forward altar. The cathedral was designed by William Wardell and built from 1866 to 1928. It is also known as St Mary's Catholic Cathedral and Chapter House, Saint Mary's Cathedral and St Mary's Cathedral. The property was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 3 September 2004.[3]

History

editBackground

editSydney was established as a penal settlement on 26 January 1788 in the name of King George III by Captain Arthur Phillip, for prisoners transported from Britain. Many of the people to arrive in Sydney at that time were military, some with wives and family; there were also some free settlers. The first chaplain of the colony was the Reverend Richard Johnson of the Church of England. No specific provision was made for the religious needs of those many convicts and settlers who were Roman Catholics. To redress this, an Irish Catholic priest, a Father O'Flynn, travelled to the colony of New South Wales but, as he arrived without government sanction, he was sent home.

It was not until 1820 that two priests, Father Conolly and Father John Therry, arrived to officially minister to the Roman Catholics in Australia. Father Conolly went to Tasmania and Father Therry remained in Sydney. Therry claimed that, on the day of his arrival, he had a vision of a mighty church of golden stone dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary raising its twin spires above the city of Sydney.[4] This vision came to pass, but not until after 180 years and three intermediate buildings.

One church after another

editFather Therry applied for a grant of land on which to build a church. He asked for land on the western side of Sydney, towards Darling Harbour. But the land allocated to him was towards the East, adjacent to a number of Governor Lachlan Macquarie's building projects, the hospital of 1811, the Hyde Park Barracks and St James' Anglican church which was also used as a law court. The more spacious site for the Catholic church overlooked a barren area upon which the bricks for Macquarie's buildings were made.[5] The area is now Hyde Park, with avenues of trees and the Archibald Fountain.

The foundation stone for the first St Mary's was laid on 29 October 1821 by Governor Macquarie. Built by James Dempsey, it was a simple cruciform stone structure which paid homage to the rising fashion for the Gothic style in its pointed windows and pinnacles. In 1835, John Polding became the first archbishop of the Roman Catholic Church in Australia. In 1851 the church was modified to the designs of Augustus Welby Pugin. Father Therry died on 25 May 1864. On 29 June 1865, the church caught fire and was destroyed.

The then archdeacon, Father McEnroe, immediately set about planning and fund raising in order to build the present cathedral, based upon a plan drawn up by Archbishop Polding. Polding wrote to William Wardell, a pupil of Augustus Welby Pugin, the most prominent architect of the Gothic Revival movement. Polding was impressed with Wardell's building of St John's College at the University of Sydney. In his letter, Polding gives Wardell a completely free hand in the design, saying "Any plan, any style, anything that is beautiful and grand, to the extent of our power."[6] Wardell had also designed and commenced work on St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne in 1858.

There were to be two intermediate stages. A temporary wooden church was constructed, which was also destroyed by fire in the summer of 1869. The third temporary provision was a sturdy brick building on the site, not of the cathedral but of St Mary's School, which it was to serve long after the present structure was in use.

Construction

editArchbishop Polding laid the foundation stone for the present cathedral in 1868.[7] It was to be a huge and ambitious structure with a wide nave and aisle and three towers. Polding did not live to see it in use as he died in 1877. Five years later, on 8 September 1882, his successor, Archbishop Vaughan, presided at the dedication Mass. Archbishop Vaughan gave the peal of bells which were rung for the first time on that day. Vaughan died while in England in 1883.

The cathedral's builder (for this stage) was John Young, who also built a large sandstone house in the Gothic Revival style, known as "The Abbey", in Annandale, New South Wales.[8]

But St Mary's was still far from finished, the work proceeding under Cardinal Moran. In 1913 Archbishop Kelly laid the foundation stone for the nave, which continued under the architects Hennessy, Hennessy and Co. In 1928 Kelly dedicated the nave in time for the commencement of the 29th International Eucharistic Congress. A slight difference of colour and texture of the sandstone on the internal walls marks the division between the first and second stage of building.

Following the death in office of Prime Minister Joseph Lyons in April 1939, he lay in state at St Mary's for several days before being taken to his home town of Devonport, Tasmania, for burial.[9]

The decoration and enrichment of the cathedral continued with the remains of Archbishop Vaughan being returned to Sydney and buried within the Chapel of the Irish Saints. The richly decorated crypt which enshrines the bodies of many of the early priests and bishops was not completed until 1961 when it was dedicated by Cardinal Gilroy.

For many years the two squared-off towers of the façade gave a disappointing appearance to an otherwise-elegant building.[citation needed] It was from time to time suggested pinnacles should be put up to match the central tower as it appeared plain that William Wardell's proposed spires would never be built. But with the assistance of a grant from the Government to mark the new millennium, the spires were eventually built in 2000.[10]

Since 2000

editIn 2008, St Mary's Cathedral became the focus of World Youth Day 2008 and was visited by Pope Benedict XVI who, in his homily on 19 July, made the historic full apology for child sex abuse by Catholic priests in Australia, of whom 107 have been committed by the courts.[11][12] On 16 December 2014, Archbishop Anthony Fisher invoked the special prayers in the Roman Missal from the "Mass in times of civil disturbance" for the victims of the 2014 Sydney hostage crisis.[13] A memorial service was held at the cathedral on the morning of 19 December for Tori Johnson and Katrina Dawson, in attendance were the Governor-General Peter Cosgrove, then-Minister of Communications Malcolm Turnbull, Senator Arthur Sinodinos, Premier of New South Wales Mike Baird, and then-Minister of Transport Gladys Berejiklian.[14][15][16]

Architecture

editPlan

editSt Mary's Cathedral is unusual among large cathedrals in that, because of its size, the plan of the city around it and the fall of the land, it is oriented in a north–south direction rather than the usual east–west. The liturgical East End is at the north and the West Front is to the south.

The plan of the cathedral is a conventional English cathedral plan, cruciform in shape, with a tower over the crossing of the nave and transepts and twin towers at the West Front (in this case, the south). The chancel is square-ended, like the chancels of Lincoln, York and several other English cathedrals. There are three processional doors in the south with additional entrances conveniently placed in the transept facades so that they lead from Hyde Park and from the presbytery buildings and school adjacent the cathedral.

Style

editThe architecture is typical of the Gothic Revival of the 19th century, inspired by the journals of the Cambridge Camden Society, the writings of John Ruskin and the architecture of Augustus Welby Pugin. At the time that the foundation stone was laid, the architect Edmund Blacket had just completed Sydney's very much smaller Anglican cathedral in the Perpendicular Gothic style and the Main Building of Sydney University. St Mary's, when William Wardell's plan was realised, was to be a much larger, more imposing and more sombre structure than the smaller St Andrew's and, because of its fortuitous siting, still dominates many views of the city despite the high-rise buildings.

The style of the cathedral is Geometric Decorated Gothic, the archaeological antecedent being the ecclesiastical architecture of late 13th century England. It is based fairly closely on the style of Lincoln Cathedral, the tracery of the huge chancel window being almost a replica of that at Lincoln.

Exterior

editThe lateral view of the building from Hyde Park is marked by the regular progression of Gothic windows with pointed arches and simple tracery. The upper roofline is finished with a pierced parapet, broken by decorative gables above the clerestorey windows, above which rises a steeply pitched slate roof with many small dormers in the French manner. The roofline of the aisles is decorated with carved bosses between the sturdy buttresses which support flying buttresses to the clerestorey.

Facing Hyde Park, the transept provides the usual mode of public entrance, as is common in many French cathedrals, and has richly decorated doors which, unlike those of the main front, have had their carved details completed and demonstrate the skills of local craftsmen in both designing and carving in the Gothic style. Included in the foliate bosses are Australian native plants such as the waratah, floral emblem of New South Wales.

St Mary's Cathedral is generally approached on foot from the city through Hyde Park, where the transept front and central tower rise up behind the Archibald Fountain. During the 20th century the gardeners of Hyde Park have further enhanced the vista by laying out a garden on the cathedral side of the park in which the plantings have often taken the form of a cross.

Despite the many English features of the architecture including its interior and chancel termination, the entrance façade is not English at all. It is a design loosely based on the most famous of all Gothic west fronts, that of Notre Dame de Paris with its balance of vertical and horizontal features, its three huge portals and its central rose window. There are two more large rose windows, one in each of the transepts. The French façade was, however, intended to have twin stone spires like those of Lichfield Cathedral, but they were not to be put in place until 132 years after the building was commenced.

The crossing tower, which holds the bells, is quite stocky but its silhouette is made elegant by the provision of tall crocketted pinnacles. The completed spires of the main front enhance the view of the cathedral along College Street and particularly the ceremonial approach from the flight of stairs in front of the cathedral. Standing at 74.6 metres (245 ft), they make St Mary's the fourth tallest church in Australia, after the triple-spired St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, St Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne and Sacred Heart Cathedral, Bendigo.

Interior

editIn cross-section the cathedral is typical of most large churches in having a high central nave and an aisle on either side, which serve to buttress the nave and provide passage around the interior. The interior of the nave thus rises in three stages, the arcade, the gallery and the clerestory which has windows to light the nave. See cathedral diagram The building is of golden-coloured sandstone which has weathered externally to golden-brown. The roof is of red cedar, that of the nave being of an open arch-braced construction enlivened by decorative pierced carvings. The chancel is vaulted with timber, which was probably intended to be richly decorated in red, blue and gold after the manner of the wooden roof at Peterborough, but this did not eventuate, and the warm colour of the timber contrasts well with the stonework.

The side aisles are vaulted in stone, with a large round boss at the centre of each ribbed vault. Children who, over the years, have crawled into the arched space beneath the pulpit have discovered another such beautiful carved boss, in miniature and usually unseen. On all the terminals of arches within the buildings are carved heads of saints. Those that are near the confessionals are at eye-level and may be examined for their details.

The screen behind the high altar is delicately carved in Oamaru limestone from New Zealand. It contains niches filled with statues like the similar niches in the altar of Our Lady located directly behind it. There are two large chapels and two smaller ones, the larger being the Chapel of the Sacred Heart and the Chapel of the Irish Saints. On either side of the Lady Chapel are the Chapels of Ss Joseph and Peter all with ornately carved altars and a small statue in each niche. The embellished mosaics in the Kelly Chapel floor were laid by Melocco Co. in 1937 approximately the same time as the mosaic floor in the Lady Chapel of St John's College also designed by Wardell.

Lighting

editBecause of the brightness of Australian sunlight, it was decided at the time of construction to glaze the clerestory with yellow glass. This glazing has darkened over the years, permitting little light to enter. The yellow glazing contrasts with the predominantly blue stained glass of the lower windows. To counteract the darkness, the cathedral installed extensive lighting in the 1970s, designed to give more-or-less equal illumination to all parts of the buildings. The interior is lit with a diffuse yellow glow, which, like the upper windows, is in contrast to the effects of the natural light which penetrates through the white areas of the stained glass. The installed lighting counteracts the pattern of light and shade that would normally exist in a cathedral of the Gothic style by illuminating most brightly those parts of the structure which would normally be subdued.

Stained glass

editThe cathedral's stained glass is all the work of Hardman & Co. and covers a period of about 50 years.

There are about 40 pictorial windows representing several themes and culminating in the chancel window showing the Fall of Man and Mary, crowned and enthroned beside Jesus as he sits in judgement, pleading Jesus' mercy upon Christians.

Other windows include the mysteries of the rosary, the birth and childhood of Jesus and lives of the saints. Stylistically, the windows move from the Gothic Revival of the 19th century to a more painterly and lavish style of the early 20th century.

- Details of the architecture

-

Carvings around the transept portal include Australian flora

-

The aisles have ribbed stone vaulting with carved bosses

-

The ceiling of the central bell tower is of painted oak

-

Western transept rose window

Treasures

editSt Mary's is full of treasures and devotional objects. Around the walls of the aisles are located the Stations of the Cross, painted in oils by L. Chovet of Paris and selected for St Mary's by Cardinal Moran in 1885. In the western transept is a marble replica of Michelangelo's Pietà, the original of which is in St. Peter's Basilica, Rome. This sculpture was brought to Australia for display in David Jones Ltd. department store and was later donated to the cathedral.

Located previously in the crypt, where it was touched in the evening by the setting sun, was the Grave of the Unknown Soldier, a realistic depiction of a dead soldier sculpted by George Washington Lambert. Although previously visible to the public from above, the tomb has now been moved into the aisle of the cathedral, to give the public greater access to it.

The crypt has an extensive mosaic floor, the achievement of Peter Melocco and his firm. This design has as its foundation a cross elaborately decorated like a vast Celtic illuminated manuscript, with rondels showing the Days of Creation and the titles of the Virgin Mary.

- Treasures of the cathedral

-

Crucifixion from the Stations of the Cross by L. Chovet

-

Decoration of the Low Altar includes a relief sculpture of the body of Jesus based on the Shroud of Turin

-

Baptistry and baptismal font

-

The Unknown Soldier by G. W. Lambert

-

Statue of Our Lady, Help of Christians in the cathedral

-

A reliquary containing a relic from the right hand of St Francis Xavier

Music

editThe music team at St Mary's currently comprises the Director of Music Daniel Justin, the Assistant Director of Music Simon Niemiński, and assistant organist Dominic Moawad; and the music administrator, Eleanor Taig.

Pipe organs

edit- The first pipe organ installed in the original cathedral was built by Henry Bevington of London and installed in June 1841. Of two manuals and 23 stops, it was the largest organ in Australia until its destruction by fire in 1865.

- In 1942 a pipe organ built by Joseph Howell Whitehouse of Brisbane, (1874–1954), was installed in the gallery at the end of the nave, above the main door.

- Between 1959 and 1971 Ronald Sharp (born 1929) installed an electric-action pipe organ in the triforium gallery of the sanctuary, but this was never completed.

- In 1997 a new pipe organ was built by Orgues Létourneau of Saint Hyacinthe, Quebec, and installed on a new gallery built around the rose window in the western transept. It was completed in 1999 and dedicated by Cardinal Clancy. The Létourneau organ is of three manuals and 46 stops. In addition to being played from the gallery, it may be played with the Whitehouse organ, from a four-manual mobile electronic console located at floor level. This console also controls the Whitehouse organ.

- A three-stop chamber organ by Henk Klop is in the Irish Saints' chapel, and is used to accompany weekday vespers.

- There is a Rodgers digital organ in the quire, which accompanies the daily choral liturgies.

- There is an organ in the crypt, made by Bellsham Pipe Organs (1985.)

Choirs

editThere are two choirs that sing liturgically at the cathedral. The Cathedral Choir sings almost daily. There is also a voluntary adult choir, the St Mary's Singers, which sings regularly for services and occasional concerts.

St Mary's Cathedral Choir

editBegun in the 19th century as a mixed voice choir, the St Mary's Cathedral Choir has been a traditional English-style cathedral choir of men and boys since 1955. There are usually 24 choristers (boy trebles and altos) and 12 lay clerks (professional altos, tenors and basses). The choir sings Mass and Vespers daily (excluding Friday) and is the oldest continuous musical institution in Australia.[17] They perform works ranging from Gregorian Chant, Sacred Polyphony and Renaissance compositions to 21st century compositions. From 2025, a treble line of girl choristers will be founded, working alongside the boy choristers.

Cathedral Scholars

editChoristers from the Cathedral Choir whose voices have broken continue their training as part of this special ensemble. The Scholars sing Vespers and Mass on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

St Mary's Singers

editThe St Mary's Singers is an adult choir of volunteer mixed voices which sings for Vespers and Mass on the third Saturday of every month, as well as at other liturgical occasions, and gives regular concerts.

Organists

edit- 1834–35 J. de C. Cavendish

- 1839 Dr J. A. Reid

- c. 1840 Dr Ross

- 1841–42 Isaac Nathan

- 1842–43 G. W. Worgan

- c. 1848–c. 1954 Mr Walton [Bishop Henry Davis is also known to have played regularly at this time]

- 1856–1870 William J. Cordner

- 1870–71 or 72 John T. Hill

- 1872[18]–1877 John A. Delany

- 1877–78 "Professor" Hughes

- 1879–1888 Thomas P. Banks

- 1888–1895 Neville G. Barnett

- 1895–1897 John A. Delany

- 1907–1963 Harry Dawkins

- 1963 Neil Slarke

- 1964–1971 Errol Scarlett

- 1971–1974 John O'Donnell

- 1974–1979 Errol Lea-Scarlett

- 1979–1987 Gavin Tipping

- 1988–2022 Peter Kneeshaw (latterly Organist Emeritus)

Bells

editThe bells of St Mary's Cathedral have a unique place in Australian history. There have been three separate rings of bells at the cathedral, all cast by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry of London. The first, of eight bells, arrived in Sydney in August 1843, and were installed in a wooden campanile located away from the main building (approximately where the pulpit is today). They were the first bells hung for change ringing in Australia and rang for the first time on New Year's Day 1844. When the cathedral was destroyed by fire in June 1865, the bells escaped damage. Construction of new cathedral began in 1866, and during 1868 the bells were removed from the campanile and installed in the new tower, which was situated where the south-western tower now stands. In 1881 the bells were traded in for a new ring of eight which were installed the following year (the Whitechapel Foundry was then using the name Mears & Stainbank). In 1885 a contract was signed for the construction of the Central Tower (the Moran Tower) to which the bells were transferred in 1898.

A century later an entirely new ring was ordered. Today the Central Tower houses a ring of twelve bells, plus two additional bells which allow alternative groups of bells to be rung, depending on the number and skill of the ringers available.[19][20] They were rung for the first time in 1986. Seven bells from the 1881 peal now form part of a ring of twelve bells at St Francis Xavier Cathedral in Adelaide.[21][22] The old tenor bell (the Moran Bell) became the Angelus bell and is located in St Mary's south-eastern tower. The bells are rung regularly before Solemn Mass on Sundays and on major feast days. They are also rung by arrangement for weddings and funerals and to mark important civic occasions. The bells of St Mary's were heard leading the ringing which marked the centenary of Australian Federation. They are also rung as part of the finale to Sydney's Symphony in the Domain concert in January, in unison with Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture. The ringing and care of the bells is entrusted to the St Mary's Basilica Society of Change Ringers, members of The Australian and New Zealand Association of Bellringers.[23][24]

Heritage listing

editAs at 30 September 2003, the cathedral site is the oldest place maintaining its use as a place of worship for the Catholic community in Australia. It is the site of the original St Mary's Cathedral, the first Catholic church in Australia and is the first land granted to the Catholic Church in Australia. It also the oldest permanent place of residence of Catholic clergy and can be said to be the birthplace of Catholicism in Australia.[3]

The cathedral is associated with significant figures in the history of the Catholic Church in Australia, notably with Father Therry, archbishops Polding and Vaughan, Cardinal Moran and Archbishop Kelly. It is also associated with important persons of the 19th and 20th centuries, including governor Macquarie and Bourke and the architects Greenway, Pugin, Wardell and Hennessy. The cathedral is the seat of the Archbishop of Sydney and the mother diocese of Australia.[3]

The cathedral is of major architectural significance as the largest 19th century ecclesiastical building in the English Gothic style anywhere in the world. The Cathedral Chapter Hall located to the east is significant as the oldest building extant on the site, possibly the oldest surviving Catholic school building in Australia and evidence to suggest an important direct involvement in its design by Pugin.[3][25]

St Mary's Catholic Cathedral was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 3 September 2004 having satisfied the following criteria.[3]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

The cathedral site is the oldest place maintaining its use as a place of worship for the Catholic community in this country. It is the site of the original St Mary's Cathedral, the first Catholic church in Australia, which was destroyed by fire in 1865. The site is significant for being the first land granted to the Catholic Church in Australia. Being the site where Governor Macquarie laid the foundation stone of the first St Mary's, the cathedral site symbolises the reconciliation of the Catholic Church and the Australian state. The site of St Mary's Cathedral is also significant as the oldest permanent place of residence of Catholic clergy in Australia. For these reasons, the site of St Mary's Cathedral can be said to be the birthplace of Catholicism in Australia.[3]

It is the place where the International Eucharistic Congresses of 1928 and 1954 were celebrated at St Mary's. The cathedral is also where the first pope to visit Australia celebrated Mass and, through its organists and choir masters, has played an important role in the musical history of Sydney. The Cathedral Chapter Hall located to the east is significant as the oldest building extant on the site. It is possibly the oldest surviving Catholic school building in Australia.[25] The use of the Chapter Hall as a school and general purpose hall has been continuous since erection and its role as an early public meeting place is highly significant. The Chapter Hall is the oldest building on the St Mary's site.[3][26]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

The cathedral is associated with significant figures in the history of the Catholic Church in Australia, notably with Father Therry, Archbishops Polding and Vaughan, Cardinal Moran and Archbishop Kelly, all of whom are buried in the crypt. It is also associated with important persons of the 19th and 20th centuries, including Governors Macquarie and Bourke, and architects Greenway, Pugin, Wardell and Hennessy.[25] The Chapter Hall's Gothic Revival style blends well with the cathedral and is aesthetically pleasing.[3][26]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

The cathedral is sited along a ridge running north–south on the eastern edge of the central area of the city and projects a dominating and inspiring presence, its roof and towers rising up above the neighbouring buildings and trees. The four arms of its plan establish axes that link it to the harbour and Woolloomooloo, to Hyde Park and to College and Macquarie streets. The long English form of the building restates and reinforces these axes, powerfully weaving the cathedral into the urban fabric. As well as providing majestic vistas from the harbour and Potts Point, from Hyde Park and the adjacent streets, and from the elevated viewpoints of many central city buildings, the cathedral offers from within beautifully framed and precious vistas of the surrounding city. It is the largest nineteenth-century ecclesiastical building in the English archaeological Gothic style anywhere in the world. The refinement and scholarship of its composition and details are of the highest rank. Together with St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, St Mary's is the major ecclesiastical work of architect William Wardell, a Gothic Revival architect of international significance practising in Australia. The cathedral is a repository of many items of aesthetic significance from the stained glass windows to the altars, statues, vestments, liturgical objects, paintings and mosaics and is important as a venue for musical events and has a considerable role in the practice of bell ringing in Australia.[25][3]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

St Mary's Cathedral is the seat of the Archbishop of Sydney and the mother diocese of Australia. In its physical and spiritual presence it proclaims the faith of the Catholic church. It is primarily a house of sacrament, prayer and worship. It is also a great civic edifice of importance to all the people of Sydney. Built on the site of the first official catholic church in the colony, the present cathedral complex links back through two centuries, without interruption, to the beginnings of the Catholic faith in Australia. It is a focus for the Catholic community of Australia, while through its musical and other artistic activities, it is an important part of the cultural life of Sydney.[25][3]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

A major sandstone building in Sydney, the physical fabric of the cathedral demonstrates the quality of craft, engineering skill and sense of place achieved in yellow block sandstone structures in Victorian Sydney. The completion of the southern front end of the cathedral by Hennessy Hennessy and Co. demonstrates innovative building technology at the beginning of this century, especially in the techniques employed in the construction of the foundations and crypt.[25][3]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

St Mary's is a rare example of the 19th century Gothic style Catholic cathedral.[25] The chapter hall is the only remaining intact building relating to John Bede Polding, the first Archbishop of Australia.[3][26]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

St Mary's Cathedral and Chapter House has represented the centre of Catholic worship and culture in Sydney (and arguably the State) since its construction in the 1870s.[3]

Gallery

edit-

Statue of St Mary of the Cross at the College Street doors

-

Chapel of the Sacred Heart

-

Chapel of St Joseph

-

Chapel of Our Lady with stained glass windows above, the reredos features statues of influential female saints

-

Chapel of St Peter with reredos depicting Jesus entrusting St Peter with the Keys to the Kingdom of Heaven

-

Chapel of the Irish Saints with reredos depicting the Crucifixion, flanked by statues of St Patrick and Brigid of Ireland.

-

The vestments of St Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh, who was implicated in the Popish Plot and executed in Tyburn.

-

A statue by Fr John Dom Eugene Gourbeillon OSB of "Our Lady and the child Jesus", the only surviving statue from the first cathedral

-

Statue of Saint Patrick presented to the cathedral by the Saint Patrick's Branch of the Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society.

-

Statue of Pope John Paul II outside the Cathedral

-

The central section in the underground crypt.

Burials in the crypt

edit- John Bede Polding

- Roger Bede Vaughan

- Patrick Francis Moran

- Michael Kelly

- Norman Thomas Gilroy

- James Darcy Freeman

- Edward Clancy

- Edward Cassidy

- John Therry, first official colonial chaplain

- John McEncroe, second official colonial chaplain

- Daniel Power

- Charles Davis, Bishop of Maitland and coadjutor bishop of Sydney

- George Pell

See also

edit- St Mary's Cathedral College, Sydney

- St. Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney, the Anglican cathedral

- The Domain, Sydney, to the north-east

References

edit- ^ "Metropolitan Archdiocese of Sydney". GCatholic.org. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Pope Pius XII (1933). Ecclesia Cathedralis Sydneyensis ad Basilicae Minoris Dignitatem Evehitur [Sydney's Cathedral Church is Elevated to the Dignity of a Minor Basililca] (PDF). Acta Apostolicae Sedis (in Latin). Vol. 25. The Holy See. pp. 200–201. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "St. Mary's Catholic Cathedral and Chapter House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01709. Retrieved 14 October 2018. Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ Freeman, Archbishop James (26 September 1971). "A threat to the bells of St Mary's". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Sternbeck, Michael (2022). "For a godly purpose: planning Saint Mary's Chapel in old Sydney-town" (PDF). Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society. 43: 1–24.

- ^ Polding's letter to Wardell, 10 October 1865

- ^ McAteer, B. "The laying of the foundation stone of St Mary's Cathedral 1868". Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society. 19 (1998) 7–8.

- ^ The Heritage of Australia. Macmillan Company. 1981. p.2/35.

- ^ Henderson, Anne (2011). Joseph Lyons: THe People's Prime Minister. UNSW Press. p. 430. ISBN 978-1-7422-4099-2.

- ^ Doherty, Tony (2022). "The story of St Mary's spires – the completion of Polding's program". Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society. 43 (2022): 167–173.

- ^ "Pope apologises for 'evil' of child sex abuse". Agence France-Presse. 18 July 2008. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Pullella, Philip (19 July 2008). "Pope apologises for Church sex abuse". Reuters UK. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Chilling terror act brought central Sydney to a halt". The Australian. Sydney. 16 December 2014. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "Sydney siege: 'Hell has touched us'". The Australian. 16 December 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "Chilling terror act brought central Sydney to a halt". The Australian. 16 December 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Kerin, Lindy (19 December 2014). "Memorial service at St Mary's Cathedral for Sydney hostage victims". The World Today. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "TV talent shows have nothing on the St Mary's Cathedral Choir when it comes to uncovering our young singing stars". The Daily Telegraph. Sydney. 31 July 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Christmas Services". Freeman's Journal. Vol. XXIII, no. 1498. Sydney. 28 December 1872. p. 10. Retrieved 1 September 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sydney, Basilica of S Mary". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "The Bells of St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney" (PDF). St Mary's Basilica Society of Change Ringers. 12 March 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Adelaide, RC Cath Ch of S Francis Xavier in Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ The Cathedral Bells Archived 19 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, website of St Francis Xavier Cathedral. Retrieved 2008-07-15

- ^ "Bell ringers". St Mary's Cathedral. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ Gibson, Caitlin (5 April 2014). "The Bell Ringers of St. Mary's". Into The Music. ABC Radio National. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g State Projects, 1995

- ^ a b c Bennett, 1987.

Bibliography

edit- Website of the Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney (http://www.sydney.catholic.org.au). 2001.

- "St Mary's Catholic Cathedral and Chapter House". 2007.

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "St Mary's Catholic Cathedral and Chapter House".

- Bennett, Robert (1987). St Mary's Cathedral Presbytery and High School Conservation Analysis.

- Heritage Office (2001). Religious Heritage Nominations.

- Kelleher, James M. (n.d.). Saint Mary's Cathedral – Pictorial Souvenir and Guide. John Fairfax and Sons Pty Ltd.

- O'Farrell, Patrick (1977). The Catholic Church and Community in Australia. Thomas Nelson (Australia), west Melbourne.

- State Projects (1995). St Mary's Cathedral Conservation Plan.

Attribution

editThis Wikipedia article contains material from St. Mary's Catholic Cathedral and Chapter House, entry number 1709 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 14 October 2018.

External links

edit- St Mary's Cathedral's official website

- St Mary's Cathedral on the Archdiocese of Sydney's official website Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- St Mary's Singers' official website

- EMBRACE – St Mary's Cathedral Youth, the youth group's official website Archived 29 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine