Selim II (Ottoman Turkish: سليم ثانى, romanized: Selīm-i sānī; Turkish: II. Selim; 28 May 1524 – 15 December 1574), also known as Selim the Blond (Turkish: Sarı Selim) or Selim the Drunkard[2] (Sarhoş Selim), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1566 until his death in 1574. He was a son of Suleiman the Magnificent and his wife Hurrem Sultan. Selim had been an unlikely candidate for the throne until his brother Mehmed died of smallpox, his half-brother Mustafa was strangled to death by the order of his father and his brother Bayezid was killed on the order of his father after a rebellion against him and Selim.

| Selim II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottoman Caliph Amir al-Mu'minin Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques | |||||

Selim's portrait c. 1570 | |||||

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Padishah) | |||||

| Reign | 7 September 1566 – 15 December 1574 | ||||

| Sword girding | 29 September 1566 | ||||

| Predecessor | Suleiman I | ||||

| Successor | Murad III | ||||

| Governor of Kütahya | |||||

| Tenure | 1562 – 1566 | ||||

| Governor of Konya | |||||

| Tenure | 1558 – 1562 | ||||

| Governor of Manisa | |||||

| Tenure | 1544 – 1558 | ||||

| Governor of Karaman | |||||

| Tenure | 1542 – 1544 | ||||

| Born | 28 May 1524 Old Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Died | 15 December 1574 (aged 50) Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Burial | Hagia Sophia, Istanbul | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Among others | Şah Sultan Gevherhan Sultan Ismihan Sultan Murad III Fatma Sultan | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman | ||||

| Father | Suleiman I | ||||

| Mother | Hürrem Sultan | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

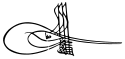

| Tughra |  | ||||

During his reign, his grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha exerted significant control over state governance. The conquest of Cyprus and Tunis were notable achievements during his reign but setbacks occurred in the Battle of Lepanto and the failed capture of Astrakhan as part of the war with Russia.

Early years

editSelim was born on 28 May 1524[3] in Constantinople during the reign of his father, Suleiman the Magnificent.[4] His mother was Hürrem Sultan,[5][6] an Orthodox priest's daughter,[7] who was the current Sultan's concubine at the time. In 1533 or 1534, his mother, Hürrem, was freed and became Suleiman's legal wife.[8][9][10] He had four brothers, Şehzade Mehmed, Şehzade Bayezid, Şehzade Abdullah and Şehzade Cihangir, and a sister Mihrimah Sultan.[5][6] In June–July 1530, a three week celebration was organised in Constantinople that centered around the circumcision of Selim, and his elder brothers Mustafa, and Mehmed.[11] The princes were circumcised on 27 June 1530.[12] The festivities ranged from displays of captured enemy items to simulated battles, featuring performances by jugglers and strongmen, as well as reenactments of recent conflicts. Suleiman played a crucial role, observing everything from a loggia in the Hippodrome, while Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha actively oversaw the proceedings and presented extravagant gifts to the sultan and the princes.[11]

In May 1537, he and his brother Mehmed joined their father on his campaign to Corfu. This marked the inaugural military campaign of his sons. Their presence in a military campaign conveyed a message of dynastic continuity.[13] In 1540, the sultan took him and Mehmed with him to spend the winter in Edirne.[14] In June 1541, he and Mehmed once again accompanied their father on his campaign to Buda.[15] In 1542, he was appointed governor of the province of Karaman, after which he went to Konya.[16] Following Mehmed's unexpected demise in November 1543, the role of district governorship of Saruhan was assumed by Selim in the spring of 1544.[17] During the summer of 1544, a gathering of family members occurred in Bursa, uniting Selim, his parents Suleiman and Hürrem, his sister Mihrimah, and Mihrimah's husband Rüstem Pasha.[18] In the 1548–49 military campaign against the Safavids, Selim was dispatched to Edirne, acting as a substitute for the sultan during the campaign.[17] In 1553, he accompanied his father against the Safavids and kept Suleiman's company throughout most of the campaign. During this campaign, his elder half-brother, Mustafa was executed on their father’s orders.[19]

Succession struggle

editIn 1555 a rebellion erupted in northeastern Bulgaria, led by a man claiming to be Şehzade Mustafa. He organised his followers like the Ottoman administration, redistributing taxes and gaining support.[20] Bayezid, aware of the situation, prepared militarily and initiated negotiations.[21] Suleiman sent Sokullu Mehmed Pasha to suppress the uprising. Bayezid's envoy convinced the pretender's chief vizier to defect, leading to the leader's capture and execution in Constantinople[22] on 31 July 1555.[23] Rumors suggested Bayezid orchestrated the revolt, but Suleiman's desire to punish him was hindered by his wife Hürrem.[23] Tensions over succession continued, with Bayezid and Selim in rivalry. Strategic maneuvers, including Bayezid's relocation to Germiyan, maintained equilibrium in their positions, both poised to return to the capital upon news of their father's fate.[24][25]

Suleiman's persistent health concerns prompted efforts to dispel rumors of imminent death. In June 1557, the French ambassador noted Suleiman's strategic display of vitality upon returning to Constantinople, countering speculations about succession plans. The dynamics shifted decisively after Hürrem's death in April 1558, known for mediating between her sons.[26] Suleiman aimed to secure the cooperation of his sons, Selim and Bayezid, in a plan to reassign them to new, distant governorates. The proposal involved moving Selim from Manisa to Konya and relocating Bayezid from Kütahya to the remote town of Amasya. Both brothers' sons were also granted governorships in smaller counties adjacent to their fathers' assignments.[27] In September, Suleiman reassigned his sons, sending Selim to Konya and Bayezid to Amasya.[28][29]

In mid-April 1559, Bayezid and his army departed Amasya and advanced toward Ankara. Despite conveying to his father his desire to return to Kütahya, it became evident that his true intention was to attack and eliminate Selim, aiming to be the sole heir to the throne before Suleiman sided with Selim. Upon learning of Bayezid's expedition, Suleiman deemed military action necessary, instructing the third vizier Sokullu Mehmed to join Selim with janissaries, accompanied by Rumeli troops.[30] Before Constantinople's forces reached Konya, Bayezid altered course southward from Ankara, arriving near Konya by late May 1559. Selim, anticipating the attack, assumed a defensive stance with augmented forces, ultimately prevailing in the engagement on May 30 and 31.[29][31]

In July 1559, Bayezid embarked on an eastern march from Amasya, accompanied by ten thousand men and four of his sons.[32] By the autumn of the same year, he reached Yerevan, a Safavid town, receiving great respect from its governor.[33] Subsequently, in October, he arrived in Qazvin,[34] where Shah Tahmasp I welcomed him initially with enthusiasm, hosting elaborate parties in his honor.[35][36] However, in April 1560, on Sultan Suleiman's request, Tahmasp imprisoned Bayezid.[34] Both Suleiman and Selim dispatched envoys to Persia to persuade Shah Tahmasp to execute Bayezid. Over the next one and a half years, embassies shuttled between Istanbul and Qazvin. The last Ottoman embassy, arriving on 16 July 1561, had the formal task of attempting to return Bayezid to Istanbul.[37] This delegation included figures like Hüsrev Pasha, Sinan Pasha, Ali Aqa Chavush Bashi, and two hundred officials.[37]

Suleiman's letter accompanying the embassy expressed his willingness to reconfirm the Treaty of Amasya (1555) and foster a new era of Ottoman–Safavid relations.[37] Throughout these diplomatic efforts, Suleiman bestowed numerous gifts on Tahmasp and agreed to pay him for handing over Bayezid—400,000 gold coins were given to Tahmasp.[38][39] Finally, on 25 September 1561,[40][41] Tahmasp handed over Bayezid and his four sons, who were subsequently executed near Qazvin by the Ottoman executioner, Ali Aqa Chavush Bashi, using the garroting method.[42][43][37] In early 1562, Selim had been appointed as the governor of Kütahya,[44] and following Bayezid's death, his last years as a prince were spent peacefully in his court in Kütahya.[45]

Reign

editAccession

editSelim ascended the throne on 29 September 1566,[46] following the death of his father on 6 September. Initially, his enthronement ceremony occurred in Istanbul, despite the presence of viziers and the military in Szigetvár, Hungary. The ceremony went unrecognised, leading to a request for a new ceremony in Belgrade.[47] On 2 October, three days later, the sultan left Istanbul.[46] In order to safeguard the process of enthronement and accession, the astute grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha maintained the secrecy of Suleiman's death until Selim arrived at the army in Belgrade.[48] In Belgrade, a throne was positioned between two tuğs (horsehair battle standards) in front of the imperial tent. The allegiance ceremony was then conducted at that location.[49] The new sultan went to Belgrade without offering the accession bonus, the standing army sought assurances of gratuity and promotion, but the sultan dismissed their request. Consequently, upon entering Istanbul, the army revolted, citing the absence of a proper enthronement ceremony.[50][51]

Character of Selim's rule

editIn this new political environment, the grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha exerted significant control over governance throughout his entire reign.[52] Mehmed Pasha served continuously as grand vizier under Suleiman, and then Selim. Known for strategically placing family members and associates in key positions across the empire, he established a reliable network of proteges. Contemporary accounts highlight Sokollu's virtual sovereignty during Selim's reign, with the grand vizier effectively managing the empire. Selim's limited involvement in governance can be attributed not only to Sokollu's dominant role but also to a significant shift in the empire's political landscape. The emergence of the court and favourites system, along with the sedentarization of the sultanate, marked Selim's reign and later became defining aspects of power struggles among his successors.[53]

Beginning with Selim, the sultans also abstained from participating in military campaigns, spending most of their time in the palace.[54] Over time during his reign, the janissaries began to increase their power at the expense of the sultan. "Acession money" demanded by the janissaries had increased; they used their power to gain more benefits for their personal lives instead of improving the state. Janissaries were now able to marry and were allowed to enrol their sons in the Corps.[55]

Treaties of Edirne and Speyer

editIn 1568, the treaty of Edirne was concluded, after which the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian II recognised recent Ottoman conquests in Hungary and continued paying an annual tribute to the sultan. The longstanding Transylvanian issue, a source of conflicts between the Habsburgs and Ottomans, found resolution in the treaty of Speyer during the imperial diet in 1570. In this treaty, John Sigismund Zápolya relinquished his title as the elected king of Hungary, adopting the titles of prince of Transylvania and the adjacent parts of Hungary. Maximilian acknowledged these changes, and John Sigismund accepted Maximilian's suzerainty over his principality, which remained a part of the Holy Crown of Hungary. Despite this, the Transylvanian prince continued to be an Ottoman vassal. In essence, the Principality of Transylvania existed in a dual dependency, with its sovereignty constrained by both the sultan and the Habsburg kings of Hungary.[56]

Astrakhan expedition

editIn 1569, Selim made an unsuccessful attempt to conquer Astrakhan.[57] One of the most ambitious endeavours during his reign, albeit left unfinished, was the construction of a canal connecting the Don and Volga rivers. Championed by Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, this extensive project involved excavating around 40 miles of challenging terrain. The canal, if completed, aimed to strategically benefit the Ottomans along the northern frontiers, serving to control Muscovy's advancement and establishing a base for potential attacks on Safavid Persia. Unfortunately, adverse weather conditions and disorder among the soldiers dispatched to the region hindered the canal's completion.[58]

Campaigns in the Mediterranean

editDuring his reign, naval campaigns unfolded in the Mediterranean.[48] In 1571, the Ottomans seized Cyprus from the Venetians,[59] transforming it into a new province alongside neighboring regions in mainland Anatolia. Initially, the island's harsh climate deterred migration, but under state pressure, a considerable number of Turkish settlers eventually established themselves. In the same year, the Holy League, comprising papal, Venetian, and Spanish fleets, retaliated for the capture of Cyprus in the decisive Battle of Lepanto, a significant Christian stronghold. The Ottoman navy suffered a devastating defeat, leading to a year-long reconstruction effort, yet the loss of skilled naval personnel continued to impact the state throughout Selim's reign. Despite this setback, the recovery of the fortress of Tunis from Spain in 1574, shortly before Selim's death, marked a notable naval success.[60]

Architecture

editSuleiman had left a lasting legacy in Damascus by commissioning the construction of the impressive Takiyya al-Sulaimaniyya mosque along the Barada River, situated outside the city walls. Designed in 1554 by the renowned architect Sinan, it was commonly referred to as the Takiyya, acknowledging the Sufi hostel (tekke or zawiyya) within its courtyard chambers. Selim expanded upon his father's mosque by adding the Madrasa Salimiyya in 1566–67. Subsequently, this complex became the starting point for the annual pilgrimage to Mecca.[61] Selim favoured Edirne over Istanbul, demonstrating his affection for the former Ottoman capital, especially relishing visits and hunting sessions in the city.[58] And so he undertook the construction of a significant mosque here. The mosque which is known as Selimiye Mosque, is the largest of all Ottoman mosques, was erected between 1569 and 1575 under the supervision of Sultan Selim's chief architect, Mimar Sinan.[62] He also undertook a significant renovation of the Hagia Sophia Mosque from 1572 to 1574 under the guidance of Sinan. This restoration included repairing the buttresses, substituting the wooden minaret with a brick one, and introducing two new minarets. Furthermore, adjacent structures were demolished to create the characteristic courtyard of the imperial mosque.[63]

Death

editSelim died after slipping and falling on a marble floor while inebriated[64] at the age of fifty on 15 December 1574.[65] He was buried in his tomb in Hagia Sophia Mosque, Istanbul.[66]

Character

editSelim was known for being a generous supporter of poets and had a strong interest in literature,[45] and wrote poems under the pen name Selimi.[67] During his time as the governor of Kütahya, he actively engaged with poetry, surrounding himself with poets, including notable figures like Turak Çelebi. Among his associates, Nigari not only served as a confidante but also played roles as an entertainer and portraitist for the sultan.[45]

He is reputed in the sources of the period to have been a generous monarch, fond of pleasure and entertainment and of drink councils, and who enjoyed the presence of scholars, poets and musicians around him. However, it is stated that he did not appear much in public, and that his father often went to Friday prayer and out among the public; Selim neglected this and spent his time in the palace.[4]

Family

editConsorts

editSelim had a Haseki and legal wife, and at least seven others concubines.[68]

- Nurbanu Sultan, his favorite concubine, Haseki Sultan, legal wife and the mother of his son and successor Sultan Murad III. During Selim's reign, her stipend was 1,100 aspers a day.[68] Selim legally married her in 1571, and bestowed upon her 110,000 ducats as a dowry, surpassing the 100,000 ducats that his father bestowed upon his mother Hürrem Sultan.[68] She died on 7 December 1583.[68]

- Other seven concubines, each mother of one of the other princes. They each received 40 aspers a day.[68] One of these concubines died just after Selim's death in December 1574, maybe suicide because of her son’s execution.[69] Another concubine died in childbirth in 1572, with her son, and a third died on 19 April 1577.[70]

Sons

editSelim had at least eight sons:

- Murad III (Manisa, 4 July 1546 – Constantinople, 15 January 1595. Buried in his mausoleum in the Hagia Sophia Mosque);[71]

- Şehzade Mehmed (1571 - September 1572, buried in the Hürrem Sultan mausoleum);[71]

- Şehzade Süleyman (1571 - 22 December 1574, executed by Murad III, buried with his father in Hagia Sophia), his mother died shortly after him;[71]

- Şehzade Abdullah (1571 - 22 December 1574, executed by Murad III, buried with his father in Hagia Sophia);[71]

- Şehzade Ali (1572 - 1572, buried with his father in Hagia Sophia). Died with his mother; [71]

- Şehzade Osman (1573 - 22 December 1574, executed by Murad III, buried with his father in Hagia Sophia);[71]

- Şehzade Mustafa (Constantinople, 1573 - Constantinople, 22 December 1574, executed by Murad III, buried with his father in Hagia Sophia);[71]

- Şehzade Cihangir (1574 - 22 December 1574, executed by Murad III, buried with his father in Hagia Sophia);[71]

Daughters

editSelim had at least four daughters:

- Şah Sultan (Karaman, c.1543[4] – Constantinople, 3 November 1580, buried in her own mausoleum, Eyüp), with Nurbanu Sultan, married firstly in 1562 to Çakırcıbaşı Hasan Pasha, married secondly in 1574 to Zal Mahmud Pasha;[72]

- Gevherhan Sultan (Manisa, 1544[4][73] - Constantinople, c.1624, buried with her father in Hagia Sophia), with Nurbanu Sultan, married firstly in 1562 to Piyale Pasha, married secondly in 1579 to Cerrah Mehmed Pasha;[72]

- Ismihan Sultan (Manisa, 1545[4][73] – Constantinople, 8 August 1585, buried with her father in Hagia Sophia), with Nurbanu Sultan, married firstly in 1562 to Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, married secondly in 1584 to Kalaylıkoz Ali Pasha;[72]

- Fatma Sultan (Konya, c. 1558 – Constantinople, October 1580, buried with her father in Hagia Sophia), with Nurbanu Sultan (disputed), married in 1573 to Kanijeli Siyavuş Pasha;[72]

In popular culture

edit- He is played by Atılay Uluışık in the 2003 Turkish TV series Hürrem Sultan.[74]

- He is portrayed by Engin Öztürk in the 2011–2014 series Muhteşem Yüzyıl (lit. 'Magnificent Century').[75]

References

edit- ^ Garo Kürkman, (1996), Ottoman Silver Marks, p.41

- ^ Somel, Selçuk Akşin (2003). Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 263. ISBN 0810843323.

- ^ Şahin 2023, pp. 121, 302.

- ^ a b c d e Emecen, Feridun (2009). "Selim II". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 36 (Sakal – Sevm) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 414–418. ISBN 978-975-389-566-8.

- ^ a b Peirce 1993, p. 60.

- ^ a b Yermolenko 2005, p. 233.

- ^ Yermolenko 2005, p. 234.

- ^ Yermolenko 2005, p. 235.

- ^ Kinross, Patrick (1979). The Ottoman centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. New York: Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-08093-8. p, 236.

- ^ The Speech of Ibrahim at the Coronation of Maximilian II, Thomas Conley, Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Summer 2002), 266.

- ^ a b Şahin 2023, p. 154.

- ^ Akbar, M.J (May 3, 2002). The Shade of Swords: Jihad and the Conflict between Islam and Christianity. Routledge. pp. 88. ISBN 978-1-134-45258-3.

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 195.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 234.

- ^ Şahin 2023, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Şahin 2023, pp. 204, 229.

- ^ a b Şahin 2023, p. 230.

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 229.

- ^ Şahin 2023, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 250.

- ^ Şahin 2013, p. 137.

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 251.

- ^ a b Şahin 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 252.

- ^ de Busbecq, O.G.; Forster, C.T.; Daniell, F.H.B. (1881). The Life and Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq. C.K. Paul. pp. 178–189.

- ^ Şahin 2013, p. 146.

- ^ Murphy 2008, p. 113–114.

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 253.

- ^ a b Çiçekler 2011, p. 212.

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 255.

- ^ Gülten 2012, p. 199.

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 256.

- ^ Clot, André (2012). Suleiman the Magnificent. Saqi. pp. 1–399. ISBN 978-0863568039.

"(...) In the autumn of 1559, the prince reached Yerevan, where the governor received him with the greatest respect. A little later, Shah Tahmasp, delighted to have such a hostage in his hands, went to Tabriz to welcome him. The shah held magnificent parties in his honour. Thirty heaped plates of gold, of silver, of pearls and precious stones, "were poured on the prince's head".

- ^ a b Şahin 2023, p. 257.

- ^ Faroqhi, Suraiya N.; Fleet, Kate (2012). The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 2, The Ottoman Empire as a World Power, 1453–1603. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1316175545.

Tahmasp, thus presented with the opportunity to take revenge for the reverse flight of his own brother some years before, received Bayezid with great honour, as Suleyman had Alkas Mirza

- ^ Clot, André (2012). Suleiman the Magnificent. Saqi. pp. 1–399. ISBN 978-0863568039.

"(...) In the autumn of 1559, the prince reached Yerevan, where the governor received him with the greatest respect. A little later, Shah Tahmasp, delighted to have such a hostage in his hands, went to Tabriz to welcome him. The shah held magnificent parties in his honour. Thirty heaped plates of gold, of silver, of pearls and precious stones, "were poured on the prince's head".

- ^ a b c d Mitchell 2009, p. 126.

- ^ Van Donzel, E.J. (1994). Islamic Desk Reference. BRILL. p. 438. ISBN 978-9004097384.

- ^ Lamb, Harold (2013). Suleiman the Magnificent - Sultan of the East. Read Books Ltd. pp. 1–384. ISBN 978-1447488088.

Four hundred thousand gold coins were sent to Tahmasp by the hand of an executioner

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 258.

- ^ Turan 1961, p. 154.

- ^ Clot, André (2012). Suleiman the Magnificent. Saqi. pp. 1–399. ISBN 978-0863568039.

Then, since he had promised never to hand him over to Suleiman, he delivered Bayezid to Selim's envoy. The unlucky man was strangled with his four sons. A little later, his fifth son, 3 years old was also put to death in Bursa by a eunuch that Suleiman had sent with a janissary.

- ^ Joseph von Hammer: Osmanlı Tarihi Vol II (condensation: Abdülkadir Karahan), Milliyet yayınları, İstanbul. p 36-37

- ^ Şahin 2023, p. 265.

- ^ a b c Fetvacı, E. (2013). Picturing History at the Ottoman Court. Indiana University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-253-00678-3.

- ^ a b Necipoğlu, G. (2010). Muqarnas, Volume 27. Brill. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-90-04-19110-5.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, pp. 208, 209.

- ^ a b A’goston & Masters 2010, p. 513.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, p. 208.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, p. 209.

- ^ McCarthy, Justin (1997). The Ottoman Turks: An Introductory History to 1923. London; New York : Longman. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-582-25656-9.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, pp. 152–153.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, pp. 513, 536.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, p. 369.

- ^ McCarthy, Justin (1997). The Ottoman Turks: An Introductory History to 1923. London; New York : Longman. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-582-25656-9.

- ^ Ágoston, G. (2023). The Last Muslim Conquest: The Ottoman Empire and Its Wars in Europe. Princeton University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-691-20539-7.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, p. 491.

- ^ a b A’goston & Masters 2010, p. 514.

- ^ Kia, Mehrdad (2017). The Ottoman Empire : a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-61069-389-9. OCLC 971893268.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, pp. 513–514.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, pp. 136, 169–170.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, p. 196.

- ^ A’goston & Masters 2010, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Darke, Diana (2022). The Ottomans: A Cultural Legacy. Thames & Hudson. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-500-77753-4.

- ^ Tezcan, B. (2010). The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern World. Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-521-51949-6.

- ^ Güzel, H.C.; Oğuz, C.; Karatay, O.; Ocak, M. (2002). The Turks. Yeni Türkiye. p. 321. ISBN 978-975-6782-58-3.

- ^ Bozkuyu, A. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu Tarihi / ÖSYM'nin Tüm Sınavları İçin Uygundur.(KPSS, TYT, AYT). Aybars Bozkuyu. p. 95.

- ^ a b c d e Peirce 1993, pp. 93–94, 129, 238, 309.

- ^ Gerlach, S.; Beydilli, K.; Noyan, T. (2007). Türkiye günlüğü: cilt. 1573-1576. Sahaftan seçmeler dizisi. Kitap Yayınevi. pp. 30–31.

- ^ Gerlach, S.; Beydilli, K.; Noyan, S.T. (2010). Türkiye günlüğü: cilt. 1577-1578. Sahaftan seçmeler dizisi. Kitap Yayınevi. pp. 561–562.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pazan, İbrahim (2023-06-06). "A Comparison of Seyyid Lokman's Records of the Birth, Death and Wedding Dates of Members of Ottoman Dynasty (1566-1595) with the Records in Ottoman Chronicles". Marmara Türkiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi. 10 (1). Marmara University: 245–271. doi:10.16985/mtad.1120498. ISSN 2148-6743.

- ^ a b c d Tezcan, Baki (2001). Searching For Osman: A Reassessment Of The Deposition Of Ottoman Sultan Osman II (1618-1622). unpublished Ph.D. thesis. pp. 327 n. 16.

- ^ a b Taner, Melis (August 2, 2011). Power to kill: a discourse of the royal hunt during the reigns of Süleyman the magnificent and Ahmed I. Sabancı University Research Database (Thesis). p. 41.

- ^ "Hürrem Sultan (TV Series 2003)". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ "Muhteşem Yüzyıl'ın 'Şehzade Selim'i Diriliş Ertuğrul'da". NTV Haber (in Turkish). March 7, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

Bibliography

edit- A’goston, Ga’bor; Masters, Bruce Alan (May 21, 2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

- Çiçekler, Mustafa (2011-12-19). "Şehzâde Bayezid Ve Farsça Divançesi". Şarkiyat Mecmuası (in Turkish) (8). İstanbul Üniversitesi. ISSN 1307-5020.

- Finkel, C. (2007). Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00850-6.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (1994). "The Official Explanations for the Confiscation and Sale of Monasteries (Churches) and their Estates at the Time of Selim II". Turcica: Revue d'études turques. 26: 34–54.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (1994). "Lʹ Eglise chrétienne dans lʹEmpire ottoman: Le monastére Chilandar à lʹépoque de Sélim II". Dialogue: Revue trimestrielle d'arts et de sciences. 12 (3): 53–64.

- Gülten, Sadullah (2017-09-24). "Kanuni'nin Maktûl Bir Şehzadesi: Bayezid". Ordu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi. 3 (6): 96–104.

- Mitchell, Collin P. (2009). The Practice of Politics in Safavid Iran: Power, Religion and Rhetoric. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857715883.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The imperial harem : women and sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507673-7. OCLC 27811454.

- Şahin, K. (2023). Peerless Among Princes: The Life and Times of Sultan Süleyman. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-753163-1.

- Turan, Şerafettin (1961). Kanunînin Oğlu Şehzade Bayezid Vak'ası. Ankara: Turk Tarih Kirumu Basimevi.

- Yermolenko, Galina (April 2005). Roxolana: "The Greatest Empresse of the East. DeSales University, Center Valley, Pennsylvania.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Selim". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

edit Media related to Selim II at Wikimedia Commons