San Ildefonso Pueblo (Tewa: Pʼohwhogeh Ówîngeh [p’òhxʷógè ʔówîŋgè] "where the water cuts through"[5][6]), also known as the Turquoise Clan,[7] is a census-designated place (CDP) in Santa Fe County, New Mexico, United States, and a federally recognized tribe, established c. 1300 C.E.[8] The Pueblo is self-governing and is part of the Santa Fe, New Mexico Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 524 as of the 2010 census,[9] reported by the State of New Mexico as 1,524 in 2012,[10] and there were 628 enrolled tribal members reported as of 2012 according to the Department of the Interior.[11] San Ildefonso Pueblo is a member of the Eight Northern Pueblos, and the pueblo people are from the Tewa ethnic group of Native Americans, who speak the Tewa language.

Pʼohwhogeh Ówîngeh | |

|---|---|

Location of San Ildefonso Pueblo | |

| Total population | |

| 750 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Tewa, English | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tewa |

San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico | |

|---|---|

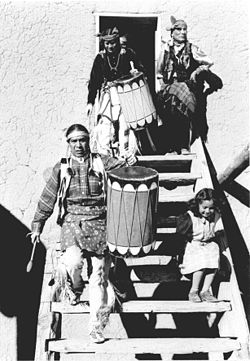

Drummers at San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1942. Ansel Adams, photographer | |

Location of San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico | |

| Coordinates: 35°53′26″N 106°07′58″W / 35.89056°N 106.13278°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Santa Fe |

| Area | |

• Total | 4.61 sq mi (11.94 km2) |

| • Land | 4.42 sq mi (11.44 km2) |

| • Water | 0.20 sq mi (0.50 km2) |

| Elevation | 5,528 ft (1,685 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 624 |

| • Density | 141.27/sq mi (54.55/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (Mountain (MST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code | 87501 |

| Area code | 505 |

| FIPS code | 35-68010 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2409256[2] |

| Website | www |

San Ildefonso Pueblo | |

| Nearest city | Espanola, New Mexico |

| Area | 46.8 acres (18.9 ha) |

| Built | 1591 |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001206[4] |

| NMSRCP No. | 230 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 20, 1974 |

| Designated NMSRCP | December 30, 1971 |

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the pueblo has a total area of 4.2 square miles (11 km2), of which 3.9 square miles (10 km2) is land and 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) (5.54%) is water.

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located at the foot of Black Mesa.

Demographics

editAs of the census[12] of 2010, there were 524 people residing in the San Ildefonso CDP. The racial makeup was 62.2% Native American, 11.3% White, 21.2% from other races, and 5.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 31.9% of the population. There were 212 households, out of which 29.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them. As of 2010, the population was distributed with 26.3% under the age of 18, 14.3% who were 65 years of age or older, females comprised 51.7%, and males comprised 48.3% of the population.

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 524 | — | |

| 2020 | 624 | 19.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13][3] | |||

As of 2000, the median income for a household in San Ildefonso was $30,000, and the median income for a family was $30,972. Males had a median income of $19,792 versus $19,250 for females. The per capita income for the pueblo was $11,039. About 19.1% of families and 14.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 50.0% of those age 65 or over.

History

editThe Pueblo was established around 1300 A.D.[14] and founded by people who had migrated from the Mesa Verde complex in Southern Colorado, by way of Bandelier (elevation about 7000 feet), just south of present-day Los Alamos, New Mexico. People thrived at Bandelier due to the rainfall and the ease of constructing living structures from the surrounding soft volcanic rock. But after a prolonged drought, the people moved down into the valleys of the Rio Grande around 1300 C.E. (Pueblo IV Era). The Rio Grande and other arroyos provided the water for irrigation.

The Spanish conquistadors tried to subdue the native people and force Catholicism on the native people during the early 17th century, which led to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The people withstood the Spaniards by climbing to the top of the Black Mesa. The siege ended with the surrender of the native people, but the Spanish gave the native people some freedom of religion and other self-governing rights.

Both the people and the lands of the Pueblo of San Ildefonso were affected by intrusion of Spanish colonists.[14] Due to these encroachments, by the 1760s some native families reported that they had no agricultural lands to support themselves.[14] Part of their lands were restored to San Ildefonso by a 1786 decision of Governor Juan Bautista de Anza.[14] Mexico took control of the area in 1821, and later the United States gained control in 1848 following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Congress created the modern reservation in 1858 confirming a grant of 17,292 acres of land to the pueblo, and the grant was patented in 1864.[14]

By the time the land was patented under the laws of the United States in 1864, there were only 161 pueblo members left.[15] A smallpox outbreak in 1918 took the population below 100.[15] The people of San Ildefonso continued to lead an agricultural based economy until the early 20th century when Maria Martinez and her husband Julian Martinez rediscovered how to make the Black-on-Black pottery for which San Ildefonso Pueblo would soon become famous. From that time the Pueblo has become more tourist-oriented, with numerous tourist shops. Because of close proximity to the state capital, Santa Fe, and the presence of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, many of those employed in the pueblo have state or federal government jobs.

Politics

editSan Ildefonso is governed by a civil government consisting of an executive branch (the governor) and a legislative branch (the tribal council).[16]

The pueblo has experienced political controversy in recent years with significant appeals to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In 2011, former pueblo Lt. Governor Paul D. Rainbird was sentenced to 33 months on federal charges of illegal trafficking in contraband cigarettes.[17] In 2012, the Interior Board of Indian Appeals vacated BIA decisions to acknowledge the results of an election for Governor of the Pueblo of San Ildefonso for the 2008/09 term which had resulted in the governorship of Leon Roybal.[18]

In 2012, the Pueblo adopted a new constitution through general election overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. One of the results of the new constitution is that, for the first time, women are allowed to run for tribal council positions.[19][20] To date, there is no publicly available copy of the newly adopted constitution.[21] The 1996 San Ildefonso Code is the most recent available copy of local laws governing the pueblo.[22]

Economic development

editThe San Ildefonso Pueblo Enterprise Corporation (SIPEC) is a federally chartered Section 17 Corporation which is wholly owned by the Pueblo de San Ildefonso.[23] SIPEC is charged with working with companies and individuals who share a vision of utilizing the Pueblo's strategic location for fostering economic and job growth for the Pueblo de San Ildefonso.

Education

editIt is zoned to Pojoaque Valley Public Schools.[24] Pojoaque Valley High School is the zoned comprehensive high school.

The Bureau of Indian Education operates the San Ildefonso Day School, an elementary school, in the pueblo.[25]

Culture

editThe people of San Ildefonso have a strong sense of identity and retain ancient ceremonies and rituals tenaciously, as well as tribal dances.[5] While many of these ceremonies and rituals are closely guarded, San Ildefonso Feast Day is open to the public every January 23.[26] Other dances open to the public include Corn Dance, which occurs in the early to mid-part of September, and dances at Easter.[27]

There was an art movement called the San Ildefonso Self-Taught Group, which included such noted artists as Alfonso Roybal, Tonita Peña, Julian Martinez, Abel Sanchez, Crecencio Martinez, and Jose Encarnacion Peña.[28]

Notable people

edit- Alfred Aguilar (b. 1933), painter and ceramicist

- José Angela "Joe" Aguilar (b. 1898), potter and painter

- José Vicente Aguilar (b. 1924), painter

- Clara Archilta (1912–1994), watercolor painter and beadworker

- Gilbert Benjamin Atencio (1930–1995), painter

- Awa Tsireh a.k.a. Alfonso Roybal (1898–1955), watercolor artist

- Crucita Calabaza also known as Blue Corn (1921–1999), pottery artist

- Joe Herrera (1923–2001), painter

- Edgar Lee Hewett (1865–1946), anthropologist, instrumental to the development of the San Ildefonso Self Taught Group

- Manuel Lujan (1928–2019), member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1969–1989), United States Secretary of Interior (1989–1993)

- Julian Martinez (1879–1943), pottery artist

- Maria Martinez (1887–1980), pottery artist

- Jose Encarnacion Peña (1902–1979), painter

- Tonita Peña (1893–1949), watercolor artist

- Oqwa Pi (also known as Abel Sanchez; 1899–1971), painter, watercolorist, muralist

- Josefa Roybal, painter, potter[29]

- Martina Vigil-Montoya (1856–1916), ceramics painter

Gallery

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico

- ^ a b "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "San Ildefonso Pueblo". Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ Burns, Patrick (2001). In the Shadow of Los Alamos: Selected Writings of Edith Warner. Albuquerque: U. New Mexico Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-8263-1974-2.

- ^ "Tablita headdress worn by women of the Turquoise Clan | National Museum of the American Indian".

- ^ "Southwest Region - Tribes Served". U.S. Department of the Interior | Bureau of Indian Affairs. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search". 2010.census.gov. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "San Ildefonso Pueblo". New Mexico Tourism Department. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "BIA Southern Plains Regional Office". U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "San Ildefonso Pueblo -- Spanish Colonial Missions of the Southwest Travel Itinerary". National Park Service. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "New Mexico: San Ildefonso". Partnership with Native Americans.

- ^ "San Ildefonso Official Website". Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "Tribal Justice News". United States Department of Justice. October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Pueblo de San Ildefonso Council of Principally v. Acting Southwest Regional Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs" (PDF). 54 IBIA 253 (02/13/2012). Interior Board of Indian Appeals. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ "Women Vote In Pueblo Election For First Time". KOAT-TV. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ "San Ildefonso Pueblo elects women for 1st time". Santa Fe New Mexican. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "San Ildefonso Pueblo Laws and Code". National Indian Law Library.

- ^ "San Ildefonso Code of 1996". National Indian Law Library.

- ^ "San Ildefonso Pueblo Enterprise Corporation". Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Santa Fe County, NM" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "San Ildefonso Day School". Bureau of Indian Education. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "Feast Days". Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ "Dances & Events at New Mexico's Native Communities". New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ Wander, Robin (February 22, 2012). "Highlights from Stanford's Native American paintings collection are showcased in Memory and Markets: Pueblo Painting in the Early 20th Century". Stanford News. Stanford University, Cantor Arts Center. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ^ "Josefa Roybal". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved June 5, 2021.