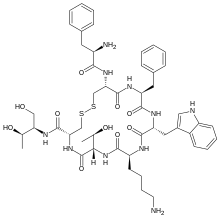

Octreotide, sold under the brand name Sandostatin among others, is an octapeptide that mimics natural somatostatin pharmacologically, though it is a more potent inhibitor of growth hormone, glucagon, and insulin than the natural hormone. It was first synthesized in 1979 and binds predominantly to the somatostatin receptors SSTR2 and SSTR5.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sandostatin, Bynfezia Pen, Mycapssa, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a693049 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous, by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60% (IM), 100% (SC) |

| Protein binding | 40–65% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1.7–1.9 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (32%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID |

|

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL |

|

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C49H66N10O10S2 |

| Molar mass | 1019.25 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

It was approved for use in the United States in 1988.[2][1] Octreotide was approved for medical use in the European Union in 2022.[4] As of June 2020[update], octreotide is the first oral somatostatin analog (SSA) approved by the FDA.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7]

Medical uses

editTumors

editOctreotide is used for the treatment of growth hormone producing tumors (acromegaly and gigantism), when surgery is contraindicated, pituitary tumors that secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone (thyrotropinoma),[citation needed] diarrhea and flushing episodes associated with carcinoid syndrome, and diarrhea in people with vasoactive intestinal peptide-secreting tumors (VIPomas). Octreotide is also used in mild cases of glucagonoma when surgery is not an option.[8][9]

Bleeding esophageal varices

editOctreotide is often given as an infusion for management of acute hemorrhage from esophageal varices in liver cirrhosis on the basis that it reduces portal venous pressure, though current evidence suggests that this effect is transient and does not improve survival.[10]

Radiolabeling

editOctreotide is used in nuclear medicine imaging by labeling with indium-111 (Octreoscan) to noninvasively image neuroendocrine and other tumours expressing somatostatin receptors.[11] It has been radiolabeled with carbon-11[12] as well as gallium-68 (using edotreotide), enabling imaging with positron emission tomography (PET).

Acromegaly

editIn June 2020, octreotide (Mycapssa) was approved for medical use in the United States with an indication for the long-term maintenance treatment in acromegaly patients who have responded to and tolerated treatment with octreotide or lanreotide.[13][6] Mycapssa is the first oral somatostatin analog (SSA) approved by the FDA.[6]

Hypoglycemia

editOctreotide is also used in the treatment of refractory hypoglycemia or congenital hyperinsulinism in neonates[14] and sulphonylurea-induced hypoglycemia in adults.

Contraindications

editOctreotide has not been adequately studied for the treatment of children as well as pregnant and lactating women. The medication is given to these groups only if a risk-benefit analysis is positive.[15][16]

Adverse effects

editThe most common adverse effects are headache, hypothyroidism, cardiac conduction changes, gastrointestinal reactions (including cramps, nausea/vomiting and diarrhoea or constipation), gallstones, reduction of insulin release, hyperglycemia[17] or sometimes hypoglycemia, and (usually transient) injection site reactions. Slow heart rate, skin reactions such as pruritus, hyperbilirubinemia, hypothyroidism, dizziness and dyspnoea are also fairly common (more than 1%). Rare side effects include acute anaphylactic reactions, pancreatitis and hepatitis.[15][16]

Some studies reported alopecia in those who were treated by octreotide.[18] Rats which were treated by octreotide experienced erectile dysfunction in a 1998 study.[19]

A prolonged QT interval has been observed, but it is uncertain whether this is a reaction to the medication or the result of an existing illness.[15]

Interactions

editOctreotide can reduce the intestinal reabsorption of ciclosporin, possibly making it necessary to increase the dose.[20] People with diabetes mellitus might need less insulin or oral antidiabetics when treated with octreotide, as it inhibits glucagon secretion more strongly and for a longer time span than insulin secretion.[15] The bioavailability of bromocriptine is increased;[16] besides being an antiparkinsonian, bromocriptine is also used for the treatment of acromegaly.

Pharmacology

editSince octreotide resembles somatostatin in physiological activities, it can:

- inhibit secretion of many hormones, such as gastrin, cholecystokinin, glucagon, growth hormone, insulin, secretin, pancreatic polypeptide, TSH, and vasoactive intestinal peptide,

- reduce secretion of fluids by the intestine and pancreas,

- reduce gastrointestinal motility and inhibit contraction of the gallbladder,

- inhibit the action of certain hormones from the anterior pituitary,

- cause vasoconstriction in the blood vessels, and

- reduce portal vessel pressures in bleeding varices.

It has also been shown to produce analgesic effects, most probably acting as a partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor.[21][22]

Pharmacokinetics

editOctreotide is absorbed quickly and completely after subcutaneous application. Maximal plasma concentration is reached after 30 minutes. The elimination half-life is 100 minutes (1.7 hours) on average when applied subcutaneously; after intravenous injection, the substance is eliminated in two phases with half-lives of 10 and 90 minutes, respectively.[15][16]

History

editOctreotide acetate was approved for use in the United States in 1988.[1][2]

In January 2020, approval of octreotide acetate in the United States was granted to Sun Pharmaceutical under the brand name Bynfezia Pen for the treatment of:[2][23][24]

- the reduction of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 (somatomedin C) in adults with acromegaly who have had inadequate response to or cannot be treated with surgical resection, pituitary irradiation, and bromocriptine mesylate at maximally tolerated doses

- severe diarrhea/flushing episodes associated with metastatic carcinoid tumors in adults

- profuse watery diarrhea associated with vasoactive intestinal peptide tumors (VIPomas) in adults

Society and culture

editLegal status

editIn September 2022, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use of the European Medicines Agency adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Mycapssa, intended for the treatment of adults with acromegaly.[25] The applicant for this medicinal product is Amryt Pharmaceuticals DAC.[25] Mycapssa was approved for medical use in the European Union in December 2022.[4][26]

Research

editOctreotide has also been used off-label for the treatment of severe, refractory diarrhea from other causes. It is used in toxicology for the treatment of prolonged recurrent hypoglycemia after sulfonylurea and possibly meglitinide overdose. It has also been used with varying degrees of success in infants with nesidioblastosis to help decrease insulin hypersecretion. Several clinical trials have demonstrated the effect of octreotide as acute treatment (abortive agent) in cluster headache, where it has been shown that administration of subcutaneous octreotide is effective when compared with placebo.[27]

Octreotide has also been investigated in people with pain from chronic pancreatitis.[28]

It has been used in the treatment of malignant bowel obstruction.[29]

Octreotide may be used in conjunction with midodrine to partially reverse peripheral vasodilation in the hepatorenal syndrome. By increasing systemic vascular resistance, these medications reduce shunting and improve renal perfusion, prolonging survival until definitive treatment with liver transplant.[30] Similarly, octreotide can be used to treat refractory chronic hypotension.[31][unreliable medical source?]

While successful treatment has been demonstrated in case reports,[32][33] larger studies have failed to demonstrate efficacy in treating chylothorax.[34]

A small study has shown[when?] that octreotide may be effective in the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension.[35][unreliable medical source?][36]

Obesity

editOctreotide has been used experimentally to treat obesity, particularly obesity caused by lesions in the hunger and satiety centers of the hypothalamus, a region of the brain central to the regulation of food intake and energy expenditure.[37] The circuit begins with an area of the hypothalamus, the arcuate nucleus, that has outputs to the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), the brain's feeding and satiety centers, respectively.[38][39] The ventromedial hypothalamus is sometimes injured by ongoing treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia or surgery or radiation to treat posterior cranial fossa tumors.[37] With the ventromedial hypothalamus disabled and no longer responding to peripheral energy balance signals, "Efferent sympathetic activity drops, resulting in malaise and reduced energy expenditure, and vagal activity increases, resulting in increased insulin secretion and adipogenesis."[40] "VMH dysfunction promotes excessive caloric intake and decreased caloric expenditure, leading to continuous and unrelenting weight gain. Attempts at caloric restriction or pharmacotherapy with adrenergic or serotonergic agents have previously met with little or only brief success in treating this syndrome."[37] In this context, octreotide suppresses the excessive release of insulin and may increase its action, thereby inhibiting excessive adipose storage. In a small clinical trial in eighteen pediatric subjects with intractable weight gain following therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia or brain tumors and other evidence of hypothalamic dysfunction, octreotide reduced body mass index (BMI) and insulin response during glucose tolerance test, while increasing parent-reported physical activity and quality of life (QoL) relative to placebo.[37] In a separate placebo-controlled trial of obese adults without known hypothalamic lesions, obese subjects who received long-acting octreotide lost weight and reduced their BMI compared to subjects receiving placebo; post hoc analysis suggested greater effects in participants receiving the higher dose of the medication, and among "Caucasian subjects having insulin secretion greater than the median of the cohort." "There were no statistically significant changes in QoL scores, body fat, leptin concentration, Beck Depression Inventory, or macronutrient intake", although subjects taking octreotide had higher blood glucose after a glucose tolerance test than those receiving placebo.[41]

References

edit- ^ a b c "Sandostatin Lar Depot- octreotide acetate kit". DailyMed. 11 April 2019. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Bynfezia Pen- octreotide acetate injection". DailyMed. 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Mycapssa- octreotide capsule, delayed release". DailyMed. 21 August 2024. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ a b c "Mycapssa EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 14 September 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ Hofland LJ, Lamberts SW (January 1996). "Somatostatin receptors and disease: role of receptor subtypes". Baillière's Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 10 (1): 163–176. doi:10.1016/s0950-351x(96)80362-4. hdl:1765/60433. PMID 8734455.

- ^ a b c "Chiasma Announces FDA Approval of Mycapssa (Octreotide) Capsules, the First and Only Oral Somatostatin Analog". Chiasma (Press release). 26 June 2020. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ Octreotide Monograph

- ^ Moattari AR, Cho K, Vinik AI (1990). "Somatostatin analogue in treatment of coexisting glucagonoma and pancreatic pseudocyst: dissociation of responses". Surgery. 108 (3): 581–7. PMID 2168587.

- ^ Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A (July 2008). "Somatostatin analogues for acute bleeding oesophageal varices". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 (3): CD000193. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000193.pub3. PMC 7043291. PMID 18677774.

- ^ "Medscape: Octreoscan review". Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ Chin J, Vesnaver M, Bernard-Gauthier V, Saucke-Lacelle E, Wängler B, Wängler C, et al. (November 2013). "Direct one-step labeling of cysteine residues on peptides with [(11)C]methyl triflate for the synthesis of PET radiopharmaceuticals". Amino Acids. 45 (5): 1097–108. doi:10.1007/s00726-013-1562-5. PMID 23921782. S2CID 16848582.

- ^ "Octreotide Capsules - Our Research". Chiasma. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ McMahon AW, Wharton GT, Thornton P, De Leon DD (January 2017). "Octreotide use and safety in infants with hyperinsulinism". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 26 (1): 26–31. doi:10.1002/pds.4144. PMC 5286465. PMID 27910218.

- ^ a b c d e Haberfeld H, ed. (2009). Austria-Codex (in German) (2009/2010 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. ISBN 978-3-85200-196-8.

- ^ a b c d Dinnendahl V, Fricke U, eds. (2010). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). Vol. 8 (23 ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ^ Hovind P, Simonsen L, Bülow J (March 2010). "Decreased leg glucose uptake during exercise contributes to the hyperglycaemic effect of octreotide". Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging. 30 (2): 141–5. doi:10.1111/j.1475-097X.2009.00917.x. PMID 20132129. S2CID 5303108.

- ^ van der Lely AJ, de Herder WW, Lamberts SW (November 1997). "A risk-benefit assessment of octreotide in the treatment of acromegaly". Drug Safety. 17 (5): 317–24. doi:10.2165/00002018-199717050-00004. PMID 9391775. S2CID 25405834.

- ^ Kapicioglu S, Mollamehmetoglu M, Kutlu N, Can G, Ozgur GK (January 1998). "Inhibition of penile erection in rats by a long-acting somatostatin analogue, octreotide (SMS 201-995)". British Journal of Urology. 81 (1): 142–5. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00520.x. PMID 9467491.

- ^ Klopp T, ed. (2010). Arzneimittel-Interaktionen (in German) (2010/2011 ed.). Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Pharmazeutische Information. ISBN 978-3-85200-207-1.

- ^ Maurer R, Gaehwiler BH, Buescher HH, Hill RC, Roemer D (August 1982). "Opiate antagonistic properties of an octapeptide somatostatin analog". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 79 (15): 4815–7. Bibcode:1982PNAS...79.4815M. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.15.4815. PMC 346769. PMID 6126877.

- ^ Allen MP, Blake JF, Bryce DK, Haggan ME, Liras S, McLean S, et al. (March 2000). "Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of 3-amino-3-phenylpropionamide derivatives as novel mu opioid receptor ligands". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 10 (6): 523–6. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00034-2. PMID 10741545.

- ^ "Bynfezia Pen letter" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 January 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Bynfezia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 June 2020. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Mycapssa: Pending EC decision". European Medicines Agency. 16 September 2022. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Mycapssa Product information". Union Register of medicinal products. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ Matharu MS, Levy MJ, Meeran K, Goadsby PJ (October 2004). "Subcutaneous octreotide in cluster headache: randomized placebo-controlled double-blind crossover study". Annals of Neurology. 56 (4): 488–94. doi:10.1002/ana.20210. PMID 15455406. S2CID 23879669.

- ^ Uhl W, Anghelacopoulos SE, Friess H, Büchler MW (1999). "The role of octreotide and somatostatin in acute and chronic pancreatitis". Digestion. 60 (2): 23–31. doi:10.1159/000051477. PMID 10207228. S2CID 24011709.

- ^ Shima Y, Ohtsu A, Shirao K, Sasaki Y (May 2008). "Clinical efficacy and safety of octreotide (SMS201-995) in terminally ill Japanese cancer patients with malignant bowel obstruction". Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 38 (5): 354–9. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyn035. PMID 18490369.

- ^ Skagen C, Einstein M, Lucey MR, Said A (August 2009). "Combination treatment with octreotide, midodrine, and albumin improves survival in patients with type 1 and type 2 hepatorenal syndrome". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 43 (7): 680–5. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e318188947c. PMID 19238094. S2CID 19747120.

- ^ Tidy C (February 2013). Cox J (ed.). "Hypotension". Patient.info. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Kilic D, Sahin E, Gulcan O, Bolat B, Turkoz R, Hatipoglu A (2005). "Octreotide for treating chylothorax after cardiac surgery". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 32 (3): 437–9. PMC 1336729. PMID 16392238.

- ^ Siu SL, Lam DS (2006). "Spontaneous neonatal chylothorax treated with octreotide". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 42 (1–2): 65–7. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00788.x. PMID 16487393. S2CID 24561126.

- ^ Chan EH, Russell JL, Williams WG, Van Arsdell GS, Coles JG, McCrindle BW (November 2005). "Postoperative chylothorax after cardiothoracic surgery in children". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 80 (5): 1864–70. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.04.048. PMID 16242470.

- ^ "Intracranial Hypertension Research Foundation". ihrfoundation.org. 17 May 2011. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Panagopoulos GN, Deftereos SN, Tagaris GA, Gryllia M, Kounadi T, Karamani O, et al. (July 2007). "Octreotide: a therapeutic option for idiopathic intracranial hypertension". Neurology, Neurophysiology, and Neuroscience: 1. PMID 17700925.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ a b c d Lustig RH, Hinds PS, Ringwald-Smith K, Christensen RK, Kaste SC, Schreiber RE, et al. (June 2003). "Octreotide therapy of pediatric hypothalamic obesity: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 88 (6): 2586–92. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-030003. PMID 12788859.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Flier JS (January 2004). "Obesity wars: molecular progress confronts an expanding epidemic". Cell. 116 (2): 337–50. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01081-X. PMID 14744442.

- ^ Boulpaep EL, Boron WF (2003). Medical physiologya: A cellular and molecular approach. Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 1227. ISBN 978-0-7216-3256-8.

- ^ Lustig RH (2011). "Hypothalamic obesity after craniopharyngioma: mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2: 60. doi:10.3389/fendo.2011.00060. PMC 3356006. PMID 22654817.

- ^ Lustig RH, Greenway F, Velasquez-Mieyer P, Heimburger D, Schumacher D, Smith D, et al. (February 2006). "A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial of a long-acting formulation of octreotide in promoting weight loss in obese adults with insulin hypersecretion". International Journal of Obesity. 30 (2): 331–41. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803074. PMC 1540404. PMID 16158082.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link)