The Lontara script (ᨒᨚᨈᨑ),[a] also known as the Bugis script, Bugis-Makassar script, or Urupu Sulapa’ Eppa’ "four-cornered letters", is one of Indonesia's traditional scripts developed in the South Sulawesi and West Sulawesi region. The script is primarily used to write the Buginese language, followed by Makassarese and Mandar. Closely related variants of Lontara are also used to write several languages outside of Sulawesi such as Bima, Ende, and Sumbawa.[1] The script was actively used by several South Sulawesi societies for day-to-day and literary texts from at least mid-15th Century CE until the mid-20th Century CE, before its function was gradually supplanted by the Latin alphabet. Today the script is taught in South Sulawesi Province as part of the local curriculum, but with very limited usage in everyday life.

| Lontara ᨒᨚᨈᨑ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | 15th century – present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Buginese, Makassarese, Mandar, (slightly modified for Bima, Ende, and Sumbawa) |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Balinese Batak Baybayin scripts Javanese Makasar Old Sundanese Rencong Rejang |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Bugi (367), Buginese |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Buginese |

| U+1A00–U+1A1F | |

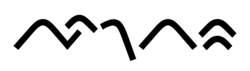

Lontara is an abugida with 23 basic letters. The script is a descendant of Brahmi through Kawi intermediaries.[2] As of other Brahmic scripts, each letter represents a syllable with an inherent vowel /a/, which can be changed with diacritics. The direction of writing is left to right. Traditionally, the script is written without word breaks (scriptio continua) and with little to no punctuation. A typical Lontara text may contain a lot of ambiguities as coda syllables, or consonants at the end of syllables, are normally not written and must be supplied by readers from context.

History

editLontara is a descendant of the Kawi script, used in Maritime Southeast Asia around 800 CE. It is unclear whether the script is a direct descendant from Kawi, or derived from one of Kawi's other descendants. One theory states that it is modelled after the Rejang script, perhaps due to their graphical similarities. But this claim may be unfounded as some characters of the Lontara are a late development.[3]

The term Lontara has also come to refer to literature regarding Bugis history and genealogy, an important subject in traditional South Sulawesi societies. Historically, Lontara was also used for a range of documents including contracts, trade laws, treaties, maps, and journals. These documents are commonly written in a contemporary-like book form, but they can be written in a traditional palm-leaf manuscript called lontar, in which a long, thin strip of dried lontar is rolled to a wooden axis in similar manner to a tape recorder. The text is then read by scrolling the lontar strip from left to right.[4]

Lontara in South Sulawesi appears to have first developed in Bugis area of the Cenrana-Walannae region at about 1400. Writing may have spread to other parts of the South Sulawesi from this region, but the possibility of independent developments cannot be dismissed. What is evident is that the earliest written records for which there is any evidence were genealogical.[5]

When paper became available in South Sulawesi in the early 17th century, Lontara script, which previously had to be written straight, angled-corner and rigid on palm leaves, could now be written faster and more variedly using ink on paper. It is worth noting that R.A. Kern (1939:580-3) writes that modified curved letters in the Lontara script one finds written on paper do not appear to have been used in the palm-leaf Bugis manuscripts he examined.[6]

Through the efforts of Dutch Linguist, B.F. Matthes, printing types of the Bugis characters, designed and cast in Rotterdam in the mid-19th century, were used from that time onwards for printing in both the South Celebes capital, Makassar, and Amsterdam. They were also used as models for teaching the script in schools, first in Makassar and environs, and then gradually in other areas of South Celebes. This process of standardization clearly influenced the later handwriting of the script. As a standard style of the script emerged, previously existing variations disappeared.[7] By the end of the 19th century, the use of the Makasar (or Jangang-Jangang script) had been completely replaced by the Lontara Bugis script, which Makassarese writers sometimes referred to as "New Lontara". [8]

Although the Latin alphabet has largely replaced Lontara, it is still used to a limited extent in Bugis and Makasar.[9] In Bugis, its usage is limited to ceremonial purposes such as wedding ceremonies. Lontara is also used extensively in printing traditional Buginese literature. In Makasar, Lontara is additionally used for personal documents such as letters and notes. Those who are skilled in writing the script are known as palontara, or 'writing specialists'.

Usage

editTraditionally, Lontara is used to write several languages of south Sulawesi. Most Lontara materials are written in the Bugis language, followed by Makassarese and (by a rather wide margin) Mandar. The Toraja people who also reside in south Sulawesi do not use the script as their literary tradition is primarily oral based, without an indigenous written form.[10] Due to Bugis-Makassar contact, modified Lontara are also used for several writing traditions outside of south Sulawesi, like the Bima, in eastern Sumbawa Island and Ende in Flores Island.[11]

| Usage of Lontara script | |

|

In historical South Sulawesi cultural sphere, the Lontara script was used in a number of related text traditions, most of which are written in manuscripts. The term lontara also refers to a literary genre that deals with history and genealogies, the most widely written and important writing topics by the Buginese and neighboring Makassar people. This genre can be divided into several sub-types: genealogy (Bugis: pangngoriseng, Makassar: pannossorang), daily registers (lontara' bilang), and chronicles (Bugis: attoriolong, Makassar: patturioloang). Each kingdom of South Sulawesi generally had their own official historiography in some compositional structure that utilized these three forms.[12] Compared to "historical" records from other parts of the archipelago, historical records in the literary tradition of South Sulawesi are decidedly more "realistic"; historical events are explained in a straightforward and plausible manner, and the relatively few fantastic elements are marked with conventional wordings so that the overall record feels factual and realistic.[13][14] Even so, such historical records are still susceptible to political meddling as a mean of ratifying power, descent, and territorial claims of ambitious rulers.[15]

The use of registers is one of south Sulawesi's unique phenomena with no known parallel in other Malay writing traditions.[16] Daily registers are often made by high ranking member of societies, such as sultans, monarchs (Bugis: arung, Makassar: karaeng), and prime ministers (Bugis: tomarilaleng, Makassar: tumailalang). The bulk of register consists of ruled columns with dates, in which the register owner would log important events in the allocated space of each date. Not all lines are filled if the corresponding dates did not have anything considered worthwhile to note, but only one line is reserved for each date. For a particularly eventful date, a writer would freely rotate the lines to fill in all available space. This may result in some pages with rather chaotic appearance of zig-zag lines that need to be rotated accordingly in order to be read.[16] One example of a royal daily register in the public collection is the daily register of Sultan Ahmad al-Salih Syamsuddin (22nd Sultan of the Boné Kingdom, reigned 1775–1812 CE), which he personally wrote from January 1, 1775 to 1795 CE.[17]

One of the most common literary work Lontara texts is the Bugis epic Sure’ Galigo ᨔᨘᨑᨛᨁᨒᨗᨁᨚ also known as I La Galigo ᨕᨗᨒᨁᨒᨗᨁᨚ. This is a long work composed of pentametric verses which relates the story of humanity's origins but also serves as practical everyday almanac. Most characters are demi-gods or their descendants spanning several generations, set in the mythological kingdoms of pre-Islamic Sulawesi. While the story took place over many episodes that can stand alone, the contents, language, and characters of each episodes are interconnected in such a way that they can be understood as part of the same Galigo. Most texts are only extracts of these episodes rather than a "complete" Galigo which would be impractical to write. Put together, writing a complete Galigo is estimated to take 6000 folio pages, making it one of the longest literary work in the world.[18] The poetical conventions and allusions of Galigo mixed with the historicalness of lontara genre would also lend to a genre of poems known as tolo’.[19]

Lontara script is also frequently found in Islamic themed texts such as hikayat (romance), prayer guide, azimat (talisman), tafsir (exegesis), and fiqh (jurisprudence).[20] Such texts are almost always written with a mixture of Arabic Jawi alphabet especially for Arabic and Malay terms. Lontara script usage in Islamic texts persisted the longest compared to other type of texts and still produced (albeit in limited manner) in the early 21st century. One of the more prolific producer of Lontara-Islamic texts is the Pesantren As'adiyah in Sengkang who published various publications with Lontara texts since the mid 20th century. However at the dawn of the 21st century, the volume and quality of Lontara publications rapidly declined. To paraphrase Tol (2015), the impression that these publications make on present readers, with their old-fashioned techniques, unattractive manufacture, and general sloppiness, is that they are very much something of the past. Today, almost no new publications are published in Lontara, and even reprints of works that originally have Lontara are often replaced by Romanized version.[21]

Contemporary use

editIn contemporary context, the Lontara script has been part of the local curriculum in South Sulawesi since the 1980s, and may be found infrequently in public signage. However, anecdotal evidence suggest that current teaching methods as well as limited and monotonous reading materials has in fact been counter productive in raising the script's literacy among younger generation. South Sulawesi youth are generally aware of the script's existence and may recognize a few letters, but it is rare for someone to able to read and write Lontara in a substantial manner. Sufficient knowledge of such manner is often limited to older generations who may still use Lontara in private works.[22][23] An example is Daeng Rahman from Boddia village, Galesong (approximately 15 km south of Makassar), who wrote various events in Galesong since 1990 in Lontara registers (similar to the chronicle genre of attoriolong/patturiolong). As of 2010, his notes spanned 12 volumes of books.[24] Old Lontara texts can sometimes be venerated as heirlooms, although modern owners who no longer able to read Lontara are prone to weave romanticized and exaggerated claims that do not reflect the actual content of the texts. For example, when researcher William Cummings conducted his study of Makassar writing tradition, a local contact told him of a Lontara heirloom in one family (whose members are all illiterate in Lontara) that no one had dared to open. After he was allowed to open the manuscript in order to check its content, it turned out to be a purchase receipt of a horse (presumably long dead by the time).[25]

Ambiguity

editLontara script does not have a virama or other ways to write syllable codas in a consistent manner, even though codas occur regularly in Bugis and Makassar. For example, the final nasal sound /-ŋ/ and glottal /ʔ/ which are common in Bugis language are entirely omitted when written in Lontara so that Bugis words like sara' (to rule), and sarang (nest) would all be written as sara (sadness) ᨔᨑ. Another example in Makassar is baba ᨅᨅ which can correspond to six possible words: baba, baba', ba'ba, ba'ba', bamba, and bambang.[26] Given that Lontara script is also traditionally written without word breaks, a typical text often has many ambiguous portions which can often only be disambiguated through context. This ambiguity is analogous to the use of Arabic letters without vowel markers; readers whose native language use Arabic characters intuitively understand which vowels are appropriate in a given sentence so that vowel markers are not needed in standard everyday texts.

Even so, sometimes even context is not sufficient. In order to read a text fluently, readers may need substantial prior knowledge of the language and contents of the text in question. As an illustration, Cummings and Jukes provide the following example to illustrate how the Lontara script can produce different meanings depending on how the reader cuts and fills in the ambiguous part:

| Lontara script | Possible reading | |

|---|---|---|

| Latin | Meaning | |

| ᨕᨅᨙᨈᨕᨗ[27] | a'bétai | he won (intransitive) |

| ambétai | he beat... (transitive) | |

| ᨊᨀᨑᨙᨕᨗᨄᨙᨄᨙᨅᨒᨉᨈᨚᨀ[28] | nakanréi pépé' balla' datoka | fire devouring a temple |

| nakanréi pépé' balanda tokka' | fire devouring a bald Hollander | |

Without knowing the actual event to which the text may be referring, it can be impossible for first time readers to determine the "correct" reading of the above examples. Even the most proficient readers may need to pause and re-interpret what they have read as new context is revealed in later portions of the same text.[26] Due to this ambiguity, some writers such as Noorduyn labelled Lontara as a defective script.[29]

Variants

edit- Lota Ende: An extended variant of the Lontara script is Lota Ende, which is used by speakers of the Ende language in central Flores.

- Mbojo: In eastern Sumbawa, another variant of the Lontara script is found, which is called the Mbojo script and used for the Bima language.[30]

- Satera Jontal: In western Sumbawa, another variant is used, called the Sumbawa script or Satera Jontal, used for the Sumbawa language.[31]

Form

editLetters

editLetters (Buginese: ᨕᨗᨊᨔᨘᨑᨛ, romanized: ina’ sure’, Makasar: ᨕᨗᨊᨔᨘᨑᨛ, romanized: anrong lontara’ ᨕᨑᨚᨒᨚᨈᨑ) represent syllables with inherent vowel /a/. There are 23 letters, shown below:[32]

ᨀ ka

|

ᨁ ga

|

ᨂ nga

|

ᨃ ngka

|

ᨄ pa

|

ᨅ ba

|

ᨆ ma

|

ᨇ mpa

|

ᨈ ta

|

ᨉ da

|

ᨊ na

|

ᨋ nra

|

ᨌ ca

|

ᨍ ja

|

ᨎ nya

|

ᨏ nca

|

ᨐ ya

|

ᨑ ra

|

ᨒ la

|

ᨓ wa

|

ᨔ sa

|

ᨕ a

|

ᨖ ha

|

There are four letters representing pre-nasalized syllables, ngka ᨃ, mpa ᨇ, nra ᨋ and nca ᨏ (represents /ɲca/, but often Romanized only as "nca" rather than "nyca"). Pre-nasalized letters are not used in Makassar materials and has so far been found only in Bugis materials. However, it has been noted that pre-nasalized letters are not used consistently and were treated more as an optional feature even by professional Bugis scribes.[33] The letter ha ᨖ is a later addition to the script for the glottal fricative due to the influence of the Arabic language.

Vowel diacritics

editDiacritics (Buginese: ᨕᨊ ᨔᨘᨑᨛ, romanized: ana’ surə’, Makasar: ᨕᨊ ᨒᨚᨈᨑ, romanized: ana’ lontara’) are used to change the inherent vowel of the letters. There are five diacritics, shown below:[32]

tetti’ riase’, ana’ i rate ◌ᨗ -i

|

tetti’ riawa, ana’ i rawa ◌ᨘ -u

|

kecce’ riolo, ana’ ri olo ᨙ -é IPA: /e/

|

kecce’ rimunri, ana’ ri boko ᨚ -o

|

kecce’ riase’, anca ◌ᨛ -e IPA: /ə/

| |

ᨊ na

|

ᨊᨗ ni

|

ᨊᨘ nu

|

ᨊᨙ né

|

ᨊᨚ no

|

ᨊᨛ ne, nang

|

- ^ The Makassarese language does not use the /ə/ sound, which is not considered phonologically distinct from the inherent vowel /a/. So, the kecce’ riase’ diacritic used in Bugis is technically not needed for writing Makassar. However, Makassar scribes are known to repurpose this diacritic to mark nasal coda /-ŋ/.[34]

Novel coda diacritics

editAs mentioned previously, Lontara script traditionally does not have any device to indicate syllable codas, except anca’ in some circumstances. The lack of coda indicator is one reason why standard Lontara texts are often very ambiguous and difficult to parse to those not already familiar with the text. Lontara variants used for Bima and Ende are known to developed viramas,[35][36] but these innovations are not absorbed back into Bugis-Makassar writing practice where lack of coda diacritics in Lontara texts is the norm until the 21st century.[36]

Users from Bugis-Makassar regions only experimented with novel coda diacritics in the early 21st century, at a time when the use of Lontara has significantly declined. Some Bugis experts describe them as necessary additions to preserve the script's cultural relevance, in addition to practical benefits such as making texts less ambiguous and teaching Lontara easier. In 2003, Djirong Basang proposed three new diacritics: virama, glottal stop, and nasal coda (akin to anusvara).[32] Anshuman Pandey recorded no less than three alternative viramas proposed in various publications up to 2016.[35] However, there are disagreements on whether new diacritics should be added to the Lontara repertoire at all. Other Bugis experts such as Nurhayati Rahman view such proposals negatively, arguing that they are often too disruptive or promoted based on simplistic and misleading premises that the so called "defectiveness" of Lontara need to be "completed" by conforming to Latin orthographical norms. Such proposals shows more of an inferiority complex that would alienate actual cultural practice and heritage from contemporary users, rather than preserve them.[37]

As of 2018, proposals of Lontara coda diacritics do not have official status or general consensus, with disparate sources prescribing different schemes.[35][38][39] The only thing agreed upon is that coda diacritics have never been attested in traditional Bugis-Makassar documents.[40]

| Bima/Ende Virama[35] |

Modern Bugis/Makassar Proposals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virama Alt.1[35] |

Virama Alt.3[35] |

Virama Alt.2[32] |

Glottal stop[32] | Nasal[32] | ||

| n | na' | nang | ||||

Punctuation

editTraditional Lontara texts are written without spaces (scriptio continua) and only use two punctuation marks, the pallawa (or passimbang in Makassar) and an end of section marker. A pallawa is used in a way similar to the Latin script comma and period, to mark pauses. An end of section marker is seen in some traditional texts and is attested in Bugis specimen sheets produced by the Imprimerie Nationale.[32][41]

pallawa ᨞

|

end of section ᨟

|

Some source may include Lontara equivalents for a number of Latin punctuations including comma, full stop, and exclamation mark, question mark. These are contemporary inventions which are unattested in traditional texts nor widely used today.[32]

Cipher

editLontara script has a traditional ciphered version called Lontara Bilang-bilang which is sometimes used specifically to write basa to bakke’ ᨅᨔ ᨈᨚ ᨅᨀᨙ, a kind of word game, and élong maliung bettuanna ᨕᨙᨒᨚ ᨆᨒᨗᨕᨘ ᨅᨛᨈᨘᨕᨊ, riddles that utilizes basa to bakke’. In élong maliung bettuanna, audience are asked to figure the correct pronunciation of a seemingly meaningless poem. When given in the form of Lontara text, the riddle giver would read the text in one way and audience may guess alternative readings of the same text to reveal the poem's hidden message.

Lontara Bilang-bilang is a substitution cipher in which the glyph of standard Lontara letters are substituted by stylized digits derived from the numeric value of corresponding Arabic alphabet. Diacritics are not changed and used as is. Similar system of cipher was also recorded in South Asian regions spanning modern Pakistan and Afghanistan, which may have inspired Lontara Bilang-bilang.[36][43]

Sample texts

editBoné Chronicles

editBelow is an extract in Buginese from the attoriolong (chronicles) of the Boné Kingdom, as written in the NBG 101 manuscript kept in the University of Leiden. This is an episode telling the descend of tomanurung, a legendary figure whose appearance marks the beginning of South Sulawesi historical kingdoms in traditional accounts.[44] Romanization and translation adapted from Macknight, Paeni & Hadrawi (2020).[45]

| Lontara[46] | Romanized[47] | Translation[48] |

|---|---|---|

| ᨕᨗᨕᨁᨑᨙᨄᨘᨈᨊᨕᨑᨘᨆᨙᨋᨙᨕᨙ᨞ᨑᨗᨁᨒᨗᨁᨚ᨞ ᨉᨙᨊᨑᨗᨕᨔᨛᨕᨑᨘ᨞ᨕᨁᨈᨛᨊᨔᨗᨔᨛᨈᨕᨘᨓᨙ᨞ᨔᨗᨕᨙᨓᨕᨉ᨞ ᨔᨗᨕᨋᨙᨅᨒᨙᨆᨊᨗᨈᨕᨘᨓᨙ᨞ᨔᨗᨕᨅᨛᨒᨗᨅᨛᨒᨗᨕ᨞ᨉᨙᨊᨕᨉᨛ᨞ ᨕᨄᨁᨗᨔᨗᨕᨑᨗᨕᨔᨛᨂᨙᨅᨗᨌᨑ᨞ᨑᨗᨕᨔᨛᨂᨗᨄᨗᨈᨘᨈᨘᨑᨛᨊᨗ᨞ ᨕᨗᨈᨊ᨞ᨉᨙᨕᨑᨘ᨞ᨔᨗᨀᨘᨓᨈᨚᨊᨗᨑᨚ᨞ᨕᨗᨈᨊ᨞ ᨈᨕᨘᨓᨙᨈᨛᨔᨗᨔᨛᨔᨗᨕᨙᨓᨕᨉ᨞ᨈᨛᨀᨙᨕᨉᨛ᨞ᨈᨛᨀᨛᨅᨗᨌᨑ᨞ |

Ia garé’ puttana arung ménré’é| riGaligo| dé’na riaseng arung| Aga tennassiseng tauwé| siéwa ada| Sianré-balémani tauwé| Siabelli-belliang| Dé’na ade’|apa’gisia riasengngé bicara| Riasengngi pitu-tturenni| ittana| dé’ arung| Sikuwa toniro| ittana| tauwé tessise-ssiéwa ada| tekké ade’| tekké bicara| | There were kings (arung), so the story goes, back in (the age of I La) Galigo, but then no longer was there anyone called king. For the people did not know how to discuss things with each other. The people just ate each other like fish do. They were selling each other all the time (as slaves). There was no longer customary order, let alone what might be called law. It is said that for the space of seven generations there was no king. For this same time also the people did not know how to discuss things with each other, nowhere was there customary order, nowhere law. |

| ᨊᨕᨗᨕᨆᨊᨗᨕᨆᨘᨒᨊ᨞ᨊᨃᨕᨑᨘ᨞ᨕᨛᨃᨔᨙᨕᨘᨓᨕᨛᨔᨚ᨞ ᨊᨔᨗᨕᨋᨙᨅᨗᨒᨕᨙ᨞ᨒᨛᨈᨙ᨞ᨄᨙᨓᨈᨚᨊᨗᨈᨊᨕᨙ᨞ᨑᨗᨕᨔᨛᨂᨗ᨞ ᨕᨛᨃᨕᨗᨔᨗᨄᨔᨆᨀᨘᨕ᨞ᨊᨕᨗᨕᨄᨍᨊᨅᨗᨒᨕᨙ᨞ᨒᨛᨈᨙ᨞ ᨄᨙᨓᨈᨊᨕᨙ᨞ᨈᨀᨚᨕᨛᨃᨈᨕᨘᨑᨗᨈ᨞ᨓᨚᨑᨚᨕᨊᨙ᨞ ᨑᨗᨈᨛᨂᨊᨄᨉᨂᨙ᨞ᨆᨔᨂᨗᨄᨘᨈᨙ᨞ᨍᨍᨗᨊᨗᨔᨗᨄᨘᨒᨘᨈᨕᨘᨓᨙ᨞ ᨈᨔᨙᨓᨊᨘᨕ᨞ᨈᨔᨙᨓᨊᨘᨕ᨞ᨕᨗᨕᨊᨑᨗᨕᨔᨗᨈᨘᨑᨘᨔᨗ᨞ ᨑᨗᨈᨕᨘᨆᨕᨙᨁᨕᨙ᨞ᨆᨔᨛᨂᨙᨂᨗ᨞ᨈᨚᨆᨊᨘᨑᨘ᨞ |

Naiamani ammulanna| nangka arung| Engka séuwa esso| nasianré billa’é| letté| péwattoni tanaé| Riasengngi| engkai sipasa makkua| Naia pajana billa’é| letté| péwang tanaé| takko’ engka tau rita| woroané| ritengngana padangngé| masangiputé| Jajini sipulung tauwé| tasséwanua| tasséwanua| Iana riassiturusi| ritau maégaé| masengngéngngi| tomanurung| | This, then, is how there began to be kings. It happened one day that the lightning and thunder raged together, the land also shook, it is said to have continued like this for one week. When the lightning, thunder and the earthquake had ceased, suddenly there was a man to be seen in the middle of the field. He was all in white. So it came about that the people gathered together, each according to his area. Then it was agreed by all the people to call him tomanurung. So it came about that all the people were of one view. Then they agreed to go together to attach themselves to this man whom they called tomanurung. |

| ᨍᨍᨗᨊᨗᨄᨔᨙᨕᨘᨓᨈᨂ᨞ᨈᨕᨘᨆᨕᨙᨁᨕᨙ᨞ᨊᨕᨗᨕᨊᨔᨗᨈᨘᨑᨘᨔᨗ᨞ ᨄᨚᨀᨛᨕᨙᨂᨗᨕᨒᨙᨊ᨞ᨒᨕᨚᨑᨗᨈᨕᨘᨓᨙᨑᨚ᨞ ᨊᨔᨛᨂᨙᨈᨚᨆᨊᨘᨑᨘ᨞ᨒᨈᨘᨕᨗᨀᨚᨑᨗᨕ᨞ᨆᨀᨛᨉᨊᨗᨈᨕᨘᨈᨛᨅᨛᨕᨙ᨞ ᨒᨊᨆᨕᨗᨀᨗᨒᨕᨚᨓᨑᨗᨀᨚ᨞ᨒᨆᨑᨘᨄᨛ᨞ᨕᨆᨔᨙᨕᨊᨀᨛ᨞ ᨕᨍᨊᨆᨘᨕᨒᨍ᨞ᨆᨘᨈᨘᨉᨊᨑᨗᨈᨊᨆᨘ᨞ᨊᨕᨗᨀᨚᨊᨄᨚᨕᨈᨀᨛ᨞ ᨕᨙᨒᨚᨆᨘᨕᨙᨒᨚᨑᨗᨀᨛ᨞ᨊᨄᨔᨘᨑᨚᨆᨘᨊᨀᨗᨄᨚᨁᨕᨘ᨞ ᨊᨆᨕᨘᨕᨊᨆᨛ᨞ᨊᨄᨈᨑᨚᨆᨛ᨞ᨆᨘᨈᨙᨕᨕᨗᨓᨗ᨞ ᨀᨗᨈᨙᨕᨕᨗᨈᨚᨕᨗᨔᨗ᨞ᨑᨙᨀᨘᨕᨆᨚᨋᨚᨆᨘᨊᨚᨆᨕᨗ᨞ ᨊᨕᨗᨀᨚᨀᨗᨄᨚᨄᨘᨕ᨞ |

Jajini passéuwa tangnga’| tau maégaé| Naia nassiturusi| pokke’éngngi aléna| llao ritauwéro| nasengngé tomanurung| Lattu’i koria| Makkedani tau tebbe’é| "Iana mai kilaowang riko| Lamarupe’| amaséannakkeng| aja’na muallajang| Mutudanna ritanamu| Naikona poatakkeng| Élo’mu élo’ rikkeng| Napassuromuna kipogau’| Namau anammeng| na patarommeng| mutéaiwi| kitéaitoisi| Rékkua monromuno mai| naiko kipopuang|" | They went there. The common people said, ‘Here we have come to you, blessed one. Have mercy on us children. Do not disappear. You have settled in your land. You have us as slaves. Your wish is what we wish. Whatever the orders, we will execute them. Even our children and our wives, (if) you reject them, we also reject them in turn. If you stay here, then we will make you lord.’ |

Unicode

editBuginese was added to the Unicode Standard in March, 2005 with the release of version 4.1.

Block

editThe Unicode block for Lontara, called Buginese, is U+1A00–U+1A1F:

| Buginese[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1A0x | ᨀ | ᨁ | ᨂ | ᨃ | ᨄ | ᨅ | ᨆ | ᨇ | ᨈ | ᨉ | ᨊ | ᨋ | ᨌ | ᨍ | ᨎ | ᨏ |

| U+1A1x | ᨐ | ᨑ | ᨒ | ᨓ | ᨔ | ᨕ | ᨖ | ◌ᨗ | ◌ᨘ | ᨙ◌ | ◌ᨚ | ◌ᨛ | ᨞ | ᨟ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Sorting order

edit- The Lontara block for Unicode use Matthes' order, in which prenasalized consonants are placed after corresponding nasal consonant, similar to how aspirated consonant would be placed following its unaspirated counterpart in standard Sanskrit. Matthes' order however, does not follow traditional Sanskrit sequence except for the first three of its consonants.

- ᨀ ᨁ ᨂ ᨃ ᨄ ᨅ ᨆ ᨇ ᨈ ᨉ ᨊ ᨋ ᨌ ᨍ ᨎ ᨏ ᨐ ᨑ ᨒ ᨓ ᨔ ᨕ ᨖ

- Lontara consonants can also be sorted or grouped according to their base shapes:

- Consonant ka ᨀ

- Consonant pa ᨄ and based on it: ga ᨁ, mpa ᨇ, nra ᨋ

- Consonant ta ᨈ and based on it: na ᨊ, ngka ᨃ, nga ᨂ, ba ᨅ, ra ᨑ, ca ᨌ, ja ᨍ, sa ᨔ

- Consonant ma ᨆ and based on it: da ᨉ

- Consonant la ᨒ

- Consonant wa ᨓ and based on it: ya ᨐ, nya ᨎ, nca ᨏ, ha ᨖ, a ᨕ

Comparison with Old Makassar script

editThe Makassar language was once written in a distinct script, the Makassar script, before it was gradually replaced by Lontara due to Bugis influence and eventually Latin in modern Indonesia. Lontara and Old Makassar script are closely related with almost identical orthography despite the graphic dissimilarities. Comparison of both scripts can be seen below:[49]

| ka | ga | nga | ngka | pa | ba | ma | mpa | ta | da | na | nra | ca | ja | nya | nca | ya | ra | la | wa | sa | a | ha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bugis | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ᨀ | ᨁ | ᨂ | ᨃ | ᨄ | ᨅ | ᨆ | ᨇ | ᨈ | ᨉ | ᨊ | ᨋ | ᨌ | ᨍ | ᨎ | ᨏ | ᨐ | ᨑ | ᨒ | ᨓ | ᨔ | ᨕ | ᨖ | |

| Makassar | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 𑻠 | 𑻡 | 𑻢 | 𑻣 | 𑻤 | 𑻥 | 𑻦 | 𑻧 | 𑻨 | 𑻩 | 𑻪 | 𑻫 | 𑻬 | 𑻭 | 𑻮 | 𑻯 | 𑻰 | 𑻱 |

| -a | -i | -u | -é[1] | -o | -e[2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | ni | nu | né | no | ne | |

| Bugis | ||||||

| ᨊ | ᨊᨗ | ᨊᨘ | ᨊᨙ | ᨊᨚ | ᨊᨛ | |

| Makassar | ||||||

| 𑻨 | 𑻨𑻳 | 𑻨𑻴 | 𑻨𑻵 | 𑻨𑻶 | ||

| Note | ||||||

| Bugis | pallawa | end of section |

|---|---|---|

| ᨞ | ᨟ | |

| Makassar | passimbang | end of section |

| 𑻷 | 𑻸 |

Gallery

edit

|

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Otherwise spelled as lontaraq or lontara' to denote the glotal stop. For completeness sake, other Bugis/Makassar terms shall use apostrophe to denote this sound whenever appropriate.

References

edit- ^ Tol 1996, pp. 213, 216.

- ^ Macknight 2016, p. 57.

- ^ Noorduyn 1993.

- ^ Tol 1996.

- ^ Druce, Stephen C. (2009). "The lands west of the lakes, A history of the Ajattappareng kingdoms of South Sulawesi 1200 to 1600 CE". KITLV Press Leiden: 63.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Druce, Stephen C. (2009). The lands west of the lakes, A history of the Ajattappareng kingdoms of South Sulawesi 1200 to 1600 CE. KITLV Press Leiden. pp. 57–63.

- ^ Jukes 2019, pp. 535.

- ^ Jukes 2019, pp. 49.

- ^ "MELESTARIKAN BUDAYA TULIS NUSANTARA: Kajian tentang Aksara Lontara". Jurnal Budaya Nusantara. Universitas PGRI Adi Buana Surabaya. 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Tol 1996, p. 213.

- ^ Tol 1996, p. 216.

- ^ Tol 1996, pp. 223–226.

- ^ Cummings 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Macknight, Paeni & Hadrawi 2020, pp. xi–xii.

- ^ Cummings 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b Tol 1996, pp. 226–228.

- ^ Gallop, Annabel Teh (1 January 2015). "The Bugis diary of the Sultan of Boné". British Library. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Tol 1996, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Tol 1996, pp. 228–230.

- ^ Tol 1996, p. 223.

- ^ Tol 2015, pp. 71, 75.

- ^ Jukes 2014, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Macknight 2016, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Jukes 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Cummings, William (2002). Making Blood White: historical transformations in early modern Makassar. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824825133.

- ^ a b Jukes 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Jukes 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Cummings 2002, p. [page needed].

- ^ Noorduyn 1993, p. 533.

- ^ Miller, Christopher (2011). "Indonesian and Philippine Scripts and extensions". unicode.org. Unicode Technical Note #35.

- ^ Pandey, Anshuman (2016). "Representing Sumbawa in Unicode" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Everson, Michael (10 May 2003). "Revised final proposal for encoding the Lontara (Buginese) script in the UCS" (PDF). Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 (N2633R). Unicode.

- ^ Noorduyn 1993, p. 544–549.

- ^ Noorduyn 1993, p. 549.

- ^ a b c d e f Pandey, Anshuman (2016-04-28). "Proposal to encode VIRAMA signs for Buginese" (PDF). Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 (L2/16–075). Unicode.

- ^ a b c Miller, Christopher (2011-03-11). "Indonesian and Philippine Scripts and extensions not yet encoded or proposed for encoding in Unicode". UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative. S2CID 676490.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rahman, Nurhayati (2012). Suara-suara dalam Lokalitas. La Galigo Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-9799911551.

- ^ Ahmad, Abd. Aziz (2018). Prosiding Seminar Nasional Lembaga Penelitian Universitas Negeri Makassar: Pengembangan tanda baca aksara Lontara. pp. 40–53. ISBN 978-602-5554-71-1.

- ^ Jukes 2014, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Tol 1996, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Kai, Daniel (2003-08-13). "Introduction to the Bugis Script" (PDF). Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 (L2/03–254). Unicode.

- ^ Matthes, B F (1883). Eenige proeven van Boegineesche en Makassaarsche Poëzie. Martinus Nijhoff.

- ^ Tol, Roger (1992). "Fish food on a tree branch; Hidden meanings in Bugis poetry". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 148 (1). Leiden: 82-102. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003169. S2CID 191975859.

- ^ Macknight, Paeni & Hadrawi 2020, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Macknight, Paeni & Hadrawi 2020, pp. 54, 77–78, 109–110.

- ^ Macknight, Paeni & Hadrawi 2020, p. 54.

- ^ Macknight, Paeni & Hadrawi 2020, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Macknight, Paeni & Hadrawi 2020, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Jukes 2014, pp. 2, Table 1.

Bibliography

edit- Campbell, George L. (1991). Compendium of the World's Languages. Routledge. pp. 267–273.

- Cummings, William P. (2007). A Chain of Kings: The Makassarese Chronicles of Gowa and Talloq. KITLV Press. ISBN 978-9067182874.

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 474, 480.

- Dalby, Andrew (1998). Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. Columbia University Press. pp. 99–100, 384. ISBN 9780713678413.

- Everson, Michael (10 May 2003). "Revised final proposal for encoding the Lontara (Buginese) script in the UCS" (PDF). Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 (N2633R). Unicode.

- Jukes, Anthony (2019-12-02). A Grammar of Makasar: A Language of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-41266-8.

- Jukes, Anthony (2014). "Writing and Reading Makassarese". International Workshop of Endangered Scripts of Island Southeast Asia: Proceedings. LingDy2 Project, Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

- Tol, Roger (1996). "A Separate Empire: Writings of South Sulawesi". In Ann Kumar; John H. McGlynn (eds.). Illuminations: The Writing Traditions of Indonesia. Jakarta: Lontar Foundation. ISBN 0834803496.

- Tol, Roger (2015). "Bugis Kitab Literature. The Phase-Out of a Manuscript Tradition". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 6: 66–90. doi:10.1163/1878464X-00601005.

- Macknight, Charles Campbell (2016). "The Media of Bugis Literacy: A Coda to Pelras". International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies. 12 (supp. 1): 53–71. doi:10.21315/ijaps2016.12.s1.4.

- Macknight, Charles Campbell; Paeni, Mukhlis; Hadrawi, Muhlis, eds. (2020). The Bugis Chronicle of Bone. Translated by Campbell Macknight; Mukhlis Paeni; Muhlis Hadrawi. Canberra: Australian National University Press. doi:10.22459/BCB.2020. ISBN 9781760463588. S2CID 218816844.

- Noorduyn, Jacobus (1993). "Variation in the Bugis/Makasarese script". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 149 (3). KITLV, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies: 533–570. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003120. S2CID 162247962.

- Sirk, Ü; Shkarban, Lina Ivanovna (1983). The Buginese Language. USSR Academy of Sciences, Institute of Oriental Studies: Nauka Publishing House, Central Department of Oriental Literature. pp. 24–26, 111–112.

External links

edit- Lontara and Makasar scripts

- Buginese script on www.ancientscripts.com

- Saweri Archived 2009-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, one font that supports only lontara script. (This font is Truetype-only, and will not properly reorder the prepended vowel /e/ to the left without the help of a compliant text-layout engine, still missing)

- Proposal to encode Bima characters