A Saucerful of Secrets is the second studio album by the English rock band Pink Floyd, released on 28 June 1968[4] by EMI Columbia in the UK and in the US by Tower Records. The mental health of the singer and guitarist Syd Barrett deteriorated during recording, so David Gilmour was recruited; Barrett left the band before the album's completion.

| A Saucerful of Secrets | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 28 June 1968 | |||

| Recorded | 9 May 1967 – 3 May 1968 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:25 | |||

| Label | EMI Columbia | |||

| Producer | Norman Smith | |||

| Pink Floyd chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from A Saucerful of Secrets | ||||

| ||||

Whereas Barrett had been the primary songwriter on Pink Floyd's debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), on A Saucerful of Secrets each member contributed songwriting and lead vocals. Gilmour appeared on all but two songs, while Barrett contributed to three.[5] "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun" is the only song on which all five members appear.

A Saucerful of Secrets reached number nine in the UK charts, but did not chart in the US until April 2019, peaking at number 158. It received mostly positive reviews, though many critics have deemed it inferior to The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.

Recording

editPink Floyd released their debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, in August 1967.[6] Work began on A Saucerful of Secrets in the same month at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) in London with the producer Norman Smith.[7] The first songs recorded were "Scream Thy Last Scream", written by the singer and guitarist, Syd Barrett, with additional vocals sung by the drummer, Nick Mason; "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun", written by the bassist, Roger Waters, and despite having only two complete takes of the song,[8][clarification needed] "Scream Thy Last Scream" was viewed as a potential single.[9] Both songs were recorded on 7 and 8 August 1967.[9][10][11] They were planned for release as a single on 8 September, but this was vetoed by Pink Floyd's record company, EMI.[12]

Following a brief European tour,[13] in early October of '67, the band returned to the studio and recorded "Vegetable Man", another Syd Barrett composition (who also performed lead vocals), and "Scream Thy Last Scream" which was again rescheduled for release, only this time with "Vegetable Man" as the B-side, but it was once again vetoed by their label EMI. The band returned on 19 October to record "Jugband Blues",[14] another Barrett composition, with Smith booking a Salvation Army band on Barrett's recommendation.[nb 1][14] During these sessions, Barrett, overdubbed slide guitar onto "Remember a Day", an outtake from The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.[17][15][18] In late October, the band took a break from the album sessions to record what was to be the third and final Pink Floyd single by Barrett, "Apples and Oranges",[14] on 26 and 27 October.[19] A few days later, they recorded what would become the B-side, "Paint Box",[14] before leaving for their first US tour.[14] On 17 November 1967, "Apples and Oranges" was released as a single following Pink Floyd's US tour. Despite the band performing it on American Bandstand on 7 November which was their US television debut, it failed to chart higher than number 55 in the UK charts, thus failing to match the chart success of their earlier singles See Emily Play and Arnold Lane.[20] Roger Waters later blamed Norman Smith's production for the single's failure to top the charts, stating "'Apples and Oranges' was destroyed by the production. It's a fucking good song".[20][21] When asked in December 1967 by Melody Maker about the song's disappointing chart run, Barrett replied he "couldn’t care less really. All we can do is make records which we like. If the kids don't, then they won't buy it. All middle men are bad."[22]

Around this time, the mental health of guitarist Syd Barrett was being called into question by the band; he was often unresponsive and would not play, leading to the cancellation of several performances and Pink Floyd's first US tour.[23] In December 1967, reaching a crisis point with Barrett, Pink Floyd added the guitarist David Gilmour as the fifth member.[24][nb 2] According to Jenner, the group planned that Gilmour would "cover for [Barrett's] eccentricities". When this proved unworkable, "Syd was just going to write. Just to try to keep him involved."[26][nb 3]

For two days from 10 January 1968, Pink Floyd reconvened at EMI Studios, attempting to work on older tracks: Waters' vocals and keyboardist Richard Wright's organ were overdubbed onto "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun",[14] while drummer Nick Mason added vocals to "Scream Thy Last Scream".[28]

From 12 January till the 20th, Pink Floyd performed briefly as a five-piece.[22] Gilmour played and sang while Barrett wandered around on stage, occasionally joining in with the playing. Between these gigs, the group rehearsed new songs written by Waters on 15 and 16 January. During the next session, on 18 January, the band jammed on rhythm tracks, joined by Smith;[nb 4][29] Barrett did not attend. On 24 and 25 January, they recorded a song logged as "The Most Boring Song I've Ever Heard Bar 2" at EMI.[nb 5][30] The band recorded "Let There Be More Light", "Corporal Clegg" (which features lead vocals by Mason),[31] and "See-Saw", all without Barrett, though manager Andrew King said Barrett performed the slide solo at the end of "Let There Be More Light".[32]

On 26 January 1968, when the band was driving to a show at Southampton University, they decided not to pick up Barrett.[22][33] Barrett was finally ousted in late January 1968, leaving the band to finish the album without him. "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun" is the only song on which all five band members appeared.[34] With Barrett removed from the sessions, the band struggled to come up with new material,[5][22] but in February 1968 recorded Wright's "It Would Be So Nice" and Waters' "Julia Dream".[nb 6][32] In early February, it was announced Waters’ track "Corporal Clegg" would be the next single;[32] however, due to pressure from the label, the song[35] was earmarked for the album, and "It Would Be So Nice" was released in April,[nb 7] with "Julia Dream" on the B-side.[36] The single failed to make the charts.[37]

Throughout April, the band took stock of their work.[36] Waters blocked "Vegetable Man"[nb 8] and "Scream Thy Last Scream" from the album. Years later Nick Mason had offered the following opinion on the two tracks not being included in the album: "they were initially intended to be potential singles, but were never satisfactorily finished. Both of these had vocals from me included in the mix, which may have had some bearing on the matter."[38] In lieu of the two songs, the band retained "Jugband Blues" and "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun".[36] Without enough material to fill an album, the band started putting together music that became the title track.[36] Mason and Waters planned it out as if it were an architectural design, including peaks and troughs.[36] Smith did not approve, telling them they had to stick to three-minute songs.[36] On 25 June, the band recorded another session for the BBC radio show Top Gear, including two tracks from the album: the session featured two tracks from Saucerful: "Let There Be More Light" and an abridged version of the title track, "The Massed Gadgets of Hercules".[39]

Songs

editUnlike The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, which was dominated by Barrett's compositions, A Saucerful of Secrets contains only one Barrett original: "Jugband Blues". AllMusic described that with A Saucerful of Secrets, "the band begin to map out the dark and repetitive pulses that would characterize their next few records."[40] Wright sings or shares lead vocals on four of the album's seven songs, and contributes vocals on the eleven-and-a-half-minute instrumental opus "A Saucerful of Secrets", making this the only Pink Floyd album where his vocal contributions outnumber those of the rest of the band.

With Barrett seemingly detached from proceedings, it came down to Waters and Wright to provide adequate material. The opening, "Let There Be More Light", written by Waters, continues the space rock approach established by Barrett on their debut LP on songs like "Astronomy Domine" and "Interstellar Overdrive". "Let There Be More Light" evolved from a bass riff that was part of "Interstellar Overdrive".[29] Both "Remember a Day" and "See-Saw" use a similar whimsical approach that Barrett had also established on their debut.[41][42] Wright remained critical of his early contributions to the band.[43]

"Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun" was first performed with Barrett in 1967.[44] The success of the track was such that it remained in their live setlist until 1973 where it appeared in a greatly extended form.[45] Waters later performed the track during solo concerts from 1984 and later.[46] Waters borrowed the lyrics from a book of Chinese poetry from the Tang dynasty, like Barrett had used in "Chapter 24".[47]

"Corporal Clegg" is the first Pink Floyd song to address issues of war, a theme which would endure throughout the career of Waters as a songwriter for the band, culminating on the 1983 album The Final Cut.[45] The title track was originally written as a new version of "Nick's Boogie".[48] The track is titled as four parts[49] on Ummagumma. A staple in the band's live set until summer 1972,[50] a live version of the song was recorded on 27 April 1969 at the Mothers Club in Birmingham for inclusion on Ummagumma.[51][52]

"Jugband Blues" is often thought to refer to Barrett's departure from the group ("It's awfully considerate of you to think of me here / And I'm most obliged to you for making it clear that I'm not here").[53][54] A promotional video was recorded for the track.[15] The band's management wanted to release the song as a single, but it was vetoed by the band and Smith.[14]

Unreleased songs

editAs well as "Jugband Blues", the album was to include "Vegetable Man", another Barrett composition.[55] The song was to appear on a single as the B-side to Barrett's "Scream Thy Last Scream".[8][10] The band performed "Jugband Blues", "Vegetable Man" and "Scream Thy Last Scream" for a Top Gear session, recorded on 20 December 1967, and broadcast on the 31st.[56] Two additional Barrett songs, "In the Beechwoods",[57] and "No Title" (frequently referred to on bootlegs as "Sunshine"),[nb 9] were recorded early in the album sessions.[58] After years of only being available via bootlegs, "Vegetable Man", "Scream Thy Last Scream", and "In the Beechwoods" were officially released on The Early Years 1965–1972 compilation. At least one other song, "John Latham", was recorded during these sessions and has been released.[58]

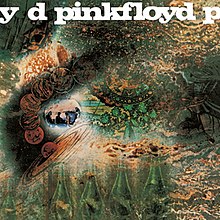

Album cover

editA Saucerful of Secrets was the first of several Pink Floyd album covers created by the design group Hipgnosis.[59] After the Beatles, it was the second time that EMI had permitted one of their acts to hire outside designers for an album jacket.[60] The cover, designed by Storm Thorgerson, contains an image of Doctor Strange from issue #158 of the comic book Strange Tales, illustrated by Marie Severin.[61][62]

Release and reception

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [40] |

| The Daily Telegraph | [63] |

| The Great Rock Discography | 8/10[64] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [65] |

| MusicHound | 2/5[66] |

| Paste | 8.3/10[67] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [68] |

| Sputnikmusic | [69] |

| Tom Hull | A−[70] |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [71] |

The album was released in the UK on 28 June 1968 on EMI's Columbia label, reaching number 9 in the UK charts.[72][73] It was released in the US by the Tower Records division of Capitol, where it was the only Pink Floyd album not to chart until 2019, when it peaked at 158.[73][74] However, when reissued as A Nice Pair with the original version of The Piper at the Gates of Dawn after the success of The Dark Side of the Moon, the album did chart at number 36 on the Billboard 200.[75] "Let There Be More Light" was released as a single, backed with "Remember a Day", in the US on 19 August 1968.[76] Rolling Stone was unfavourable, writing that the album was "not as interesting as their first" and "rather mediocre", highlighting the reduced contributions from Barrett.[77] However, in recent years via The Rolling Stone Album Guide, it was given an updated rating of 3 stars, which indicates a positive rating.

The stereo mix of the album was first released on CD in 1988, and in 1992 was digitally remastered and reissued as part of the Shine On box set.[78] The remastered stereo CD was released on its own in 1994 in the UK and the US. The mono version of the album has never been officially released on CD. The stereo mix was remastered and re-issued in 2011 by Capitol/EMI as part of the Why Pink Floyd: Discovery series,[79] and again in 2016 by Sony Music under the Pink Floyd Records label.[80] The mono mix was reissued on vinyl for Record Store Day in April 2019 by Sony Music and Warner Music Group under the Pink Floyd Records label.[81] The album finally charted on the Billboard 200 as a standalone peaking at No. 158 when the mono mix was re-released for Record Store Day.[82]

In a retrospective review for AllMusic, Richie Unterberger draws attention to the album's "gentle, fairy-tale ambience", with songs that move from "concise and vivid" to "spacy, ethereal material with lengthy instrumental passages".[40] In a review for BBC Music, Daryl Easlea said Saucerful was "not without filler", adding that "Jugband Blues" was "the most chilling" song on the album.[83]

In 2014, Mason named A Saucerful of Secrets his favourite Pink Floyd album: "I think there are ideas contained there that we have continued to use all the way through our career. I think [it] was a quite good way of marking Syd's departure and Dave's arrival. It's rather nice to have it on one record, where you get both things. It's a cross-fade rather than a cut."[84]

Track listing

edit| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Let There Be More Light" | Roger Waters | Richard Wright and David Gilmour | 5:38 |

| 2. | "Remember a Day" | Wright | Wright | 4:33 |

| 3. | "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun" | Waters | Waters | 5:28 |

| 4. | "Corporal Clegg" | Waters | Gilmour, Nick Mason and Wright | 4:12 |

| Total length: | 19:52 | |||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. | "A Saucerful of Secrets"

| Waters, Wright, Mason, Gilmour | instrumental, wordless vocals by Gilmour and Wright | 11:57 |

| 6. | "See-Saw" | Wright | Wright | 4:36 |

| 7. | "Jugband Blues" | Syd Barrett | Barrett | 3:00 |

| Total length: | 19:33 (39:25) | |||

Personnel

editTrack numbers noted in parentheses below are based on CD track numbering.

Pink Floyd

- David Gilmour – guitars (all except 2 and 7), kazoo (4), vocals[45]

- Nick Mason – drums (all except 2), percussion (1, 5, 6, 7), lead vocals (4),[31] kazoo (7)[85]

- Roger Waters – bass guitar (all tracks), percussion (3, 5), vocals[45]

- Richard Wright – Farfisa organ (all tracks), piano (1, 2, 5, 6), Hammond organ (1, 4, 5), Mellotron (5, 6), vibraphone (3, 5), celesta (3), xylophone (6), tin whistle (7), vocals

- Syd Barrett – vocals (7), slide guitar (2), acoustic guitar (2, 7), electric guitar (3, 7)

Additional personnel

- Norman Smith – producer,[86] drums (2), backing vocals (2, 6),[18] voice (5)

- The Stanley Myers Orchestra (4)

- The Salvation Army (The International Staff Band) – brass section (7)[14]

Charts

edit| Chart (1968) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Albums (OCC)[87] | 9 |

| Chart (2006) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Italian Albums (FIMI)[88] | 24 |

| Chart (2011) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| French Albums (SNEP)[89] | 166 |

| Chart (2016) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[90] | 57 |

| Chart (2019) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard 200[91] | 158 |

| Chart (2022) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Hungarian Albums (MAHASZ)[92] | 35 |

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Italy (FIMI)[93] sales since 2009 |

Gold | 25,000‡ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[94] 1994 release |

Gold | 100,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

editFootnotes

- ^ When the Salvation Army were brought in to play on the track,[15] Barrett's instructions to Smith were "let them play whatever they want", while Smith had insisted on composed parts versus improvisation.[16]

- ^ In late 1967, Barrett suggested adding four new members; in the words of Waters: "two freaks he'd met somewhere. One of them played the banjo, the other the saxophone ... [and] a couple of chick singers".[25]

- ^ One of Gilmour's first tasks was to mime Barrett's guitar playing on an "Apples and Oranges" promotional film.[27]

- ^ This jamming later formed the intro to "Let There Be More Light".[29]

- ^ This song later became "See-Saw".[10]

- ^ Originally titled "Doreen's Dream".[32]

- ^ The single was released on 12 April 1968, almost a week after Barrett's departure from the band was announced.[36]

- ^ Peter Jenner, one of the band's managers, said Waters blocked "Vegetable Man" because "it was too dark".[17]

- ^ Not to be confused with the early title of "Remember a Day", as written on the recorded sheet, "Sunshine".[10][14]

Citations

- ^ Edmondson PhD, Jacqueline (10 May 2011). Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars, and ... Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4299-6589-7. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

...Although Pink Floyd found its own origins in the psychedelic rock of the late 1960s—most notably in The Piper at the Gates of Dawn(1967) and A Saucerful of Secrets(1968)...

- ^ Bill Martin (14 December 2015). Avant Rock: Experimental Music from the Beatles to Bjork. Open Court. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-4299-6589-7. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Bill Martin (14 December 2015). Listening to the Future: The Time of Progressive Rock, 1968–1978. Open Court. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4299-6589-7. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Timeline". Pink Floyd - The Official Site. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ a b Gulla, Bob (2009). Guitar Gods: The 25 Players Who Made Rock History. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-313-35806-7.

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 391.

- ^ Jones, Malcolm (2003), The Making of The Madcap Laughs (21st Anniversary ed.), Brain Damage, pp. 23–25

- ^ a b Chapman, Rob (2010). Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head (Paperback ed.). London: Faber. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-571-23855-2.

- ^ a b Palacios 2010, p. 262

- ^ a b c d Jones 2003, p. 23

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 186

- ^ Palacios 1998, p. 180

- ^ "The Pink Floyd Archives-Pink Floyd Concert Appearances".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Manning 2006, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Palacios 2010, p. 286

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 191

- ^ a b Palacios 1998, p. 194

- ^ a b Everett, Walter (2009). The Foundations of Rock: From "Blue Suede Shoes" to "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes". Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-19-531023-8.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 189

- ^ a b Manning 2006, p. 43.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d Carruthers, Bob. Pink Floyd – Uncensored on Record. Coda Books Ltd. ISBN 1-908538-27-9. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ Povey 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Povey 2008, p. 47.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 110.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 107.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 104.

- ^ Palacios, Julian (2010). Syd Barrett & Pink Floyd: Dark Globe (Rev. ed.). London: Plexus. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-85965-431-9.

- ^ a b c Palacios 2010, p. 319

- ^ Povey 2006, p. 90

- ^ a b Schaffner 1991, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d Manning 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Blake, Mark (2008). Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-306-81752-6.

- ^ 1993 Guitar World interview with David Gilmour

- ^ Manning 2006, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b c d e f g Manning 2006, p. 47.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | the Official Site".

- ^ https://www.neptunepinkfloyd.co.uk/forum/viewtopic.php?t=7994&start=30 [bare URL]

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Unterberger, Richie. "A Saucerful of Secrets – Pink Floyd : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards : AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 285

- ^ Reisch 2007, p. 272

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 271

- ^ a b c d Mabbett, Andy (1995). The Complete Guide to the Music of Pink Floyd. London: Omnibus. ISBN 0-7119-4301-X.

- ^ Sweeting, Adam (20 May 2008). "Roger Waters: set the controls for the heart of the Floyd". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 265

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 322

- ^ "Echoes FAQ Ver, 4.0 – 4/10". Pink-floyd.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 188.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 156.

- ^ Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd – The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- ^ Reisch 2007, p. 236

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 190

- ^ Reisch, George A., ed. (2007). Pink Floyd and Philosophy: Careful With That Axiom, Eugene! (1st ed.). Chicago: Open Court. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-8126-9636-3.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 44.

- ^ Chapman 2010, p. 193

- ^ a b Jones 2003, p. 25

- ^ Palacios 2010, p. 330

- ^ Roberts, James. "Hipgnotic Suggestion". Frieze (37). Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ "Marie Severin". lambiek.net. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "The Doctor Strange and Pink Floyd Connection". Den of Geek. 6 January 2020.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (20 May 2014). "Pink Floyd's 14 studio albums rated". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Strong, Martin C. (2004). The Great Rock Discography (7th ed.). New York: Canongate. p. 1176. OL 18807297M.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857125958. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 872. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ^ Deusner, Stephen (16 October 2011). "Assessing a Legacy: Why Pink Floyd? Reissue Series". Paste. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (2 November 2004). "Pink Floyd: Album Guide". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media, Fireside Books. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ "A Saucerful of Secrets – Pink Floyd". Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Hull, Tom. "Grade List: pink floyd". Tom Hull – on the Web. Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Larkin, Colin, ed. (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus. p. 1105. OL 11913831M.

- ^ "Pink Floyd – UK Chart History". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ a b Povey 2006, p. 343.

- ^ "A Saucerful of Secrets – Pink Floyd | Billboard". billboard.com. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ "A Nice Pair – Pink Floyd : Awards : AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Fitch, Vernon. "Pink Floyd Archives-Tower Records Discography". Pinkfloydarchives.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Miller, Jim (26 October 1968). "A Saucerful of Secrets". Rolling Stone. San Francisco: Straight Arrow Publishers, Inc. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Povey 2006, p. 535.

- ^ Fowler, Peter (10 May 2011). "Pink Floyd To Release New Album Including Unreleased Songs". newsroomamerica.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ A Saucerful of Secrets (Media notes). Pink Floyd Records. 2016. PFR2.

- ^ Grow, Kory (27 February 2019). "Pink Floyd Plot 'Saucerful of Secrets' Mono Mix Reissue for Record Store Day". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Top 200 Albums". Billboard. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Easlea, Daryl (17 April 2007). "Music – Review of Pink Floyd – A Saucerful of Secrets". BBC. Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (7 November 2014). "Pink Floyd's Longest-Serving Officer". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 187.

- ^ A Saucerful of Secrets (Back cover). Pink Floyd. EMI Columbia.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – A Saucerful of Secrets". Hung Medien. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Pink Floyd – A Saucerful of Secrets". Hung Medien. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Pink Floyd – A Saucerful of Secrets" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2022. 18. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Saucerful of Secrets" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 5 January 2021. Select "2020" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "A Saucerful of Secrets" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "British album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Saucerful of Secrets". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

Bibliography

edit- Manning, Toby (2006). The Rough Guide to Pink Floyd (1st ed.). London: Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-575-0.

- Povey, Glenn (2006). Echoes : The Complete History of Pink Floyd (New ed.). Mind Head Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5.

- Povey, Glenn (2008) [2007]. Echoes: The Complete History of Pink Floyd. Mind Head Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9554624-1-2.

- Roberts, David, ed. (2005). British Hit Singles & Albums (18 ed.). Guinness World Records Limited. ISBN 978-1-904994-00-8.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1991). Saucerful of Secrets (First ed.). Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-06127-1.

External links

edit- A Saucerful of Secrets at Discogs (list of releases)