The scaphoid bone is one of the carpal bones of the wrist. It is situated between the hand and forearm on the thumb side of the wrist (also called the lateral or radial side). It forms the radial border of the carpal tunnel. The scaphoid bone is the largest bone of the proximal row of wrist bones, its long axis being from above downward, lateralward, and forward. It is approximately the size and shape of a medium cashew nut.

| Scaphoid bone | |

|---|---|

Left hand anterior view (palmar view). Scaphoid bone shown in red. | |

The left scaphoid bone | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈskæfɔɪd/ |

| Articulations | Articulates with five bones radius proximally trapezoid bone and trapezium bone distally capitate and lunate medially |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os scaphoideum, os naviculare manus |

| MeSH | D021361 |

| TA98 | A02.4.08.003 |

| TA2 | 1250 |

| FMA | 23709 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Structure

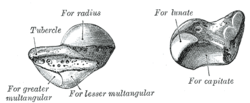

editThe scaphoid is situated between the proximal and distal rows of carpal bones. It is located on the radial side of the wrist,[1]: 176 adjacent to the styloid process of the radius.[2] It articulates with the radius, lunate, trapezoid, trapezium, and capitate.[1]: 176 Over 80% of the bone is covered in articular cartilage.[3]

Bone

editThe palmar surface of the scaphoid is concave, and forming a distal tubercle, giving attachment to the transverse carpal ligament. The proximal surface is triangular, smooth and convex.[3] The lateral surface is narrow and gives attachment to the radial collateral ligament. The medial surface has two facets, a flattened semi-lunar facet articulating with the lunate bone, and an inferior concave facet, articulating alongside the lunate with the head of the capitate bone.[4]

The dorsal surface of the bone is narrow, with a groove running the length of the bone and allowing ligaments to attach, and the surface facing the fingers (anatomically inferior) is smooth and convex, also triangular, and divided into two parts by a slight ridge.[4]

Blood supply

editIt receives its blood supply primarily from lateral and distal branches of the radial artery, via palmar and dorsal branches. These provide an "abundant" supply to middle and distal portions of the bone, but neglect the proximal portion, which relies on retrograde flow.[1]: 189 The dorsal branch supplies the majority of the middle and distal portions, with the palmar branch supplying only the distal third of the bone.[3]

Variation

editThe dorsal blood supply, particularly of the proximal portion, is highly variable.[1]: 189 Sometimes the fibers of the abductor pollicis brevis emerge from the tubercle.[4]

In animals

editIn reptiles, birds, and amphibians, the scaphoid is instead commonly referred to as the radiale because of its articulation with the radius.

Function

editThe carpal bones function as a unit to provide a bony superstructure for the hand.[5]: 708 The scaphoid is also involved in movement of the wrist.[1]: 6 It, along with the lunate, articulates with the radius and ulna to form the major bones involved in movement of the wrist.[5] The scaphoid serves as a link between the two rows of carpal bones. With wrist movement, the scaphoid may flex from its position in the same plane as the forearm to perpendicular.[1]: 176–177

Clinical significance

editFracture

editFractures of the scaphoid are the most common of the carpal bone injuries, because of its connections with the two rows of carpal bones.[1]: 177

The scaphoid can be slow to heal because of the limited circulation to the bone. Fractures of the scaphoid must be recognized and treated quickly, as prompt treatment by immobilization or surgical fixation increases the likelihood of the bone healing in anatomic alignment, thus avoiding mal-union or non-union.[6] Delays may compromise healing. Failure of the fracture to heal ("non-union") will lead to post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the carpus.[1]: 189 One reason for this is because of the "tenuous" blood supply to the proximal segment.[3] Even rapidly immobilized fractures may require surgical treatment, including use of a headless compression screw such as the Herbert screw to bind the two halves together.

Healing of the fracture with a non-anatomic deformity (frequently, a volar flexed "humpback") can also lead to post-traumatic arthritis. Non-unions can result in loss of blood supply to the proximal pole, which can result in avascular necrosis of the proximal segment.

Scaphoid fractures may be difficult to diagnose via plain x-ray. A repeat x-ray may be required at a later date, as might cross-sectional imaging via MRI or CT scan.[6]

Other diseases

editA condition called scapholunate instability can occur when the scapholunate ligament (connecting the scaphoid to the lunate bone) and other surrounding ligaments are disrupted. In this state, the distance between the scaphoid and lunate bones is increased.[1]: 180

One rare disease of the scaphoid is called Preiser's Disease.

Palpation

editThe scaphoid can be palpated at the base of the anatomical snuff box. It can also be palpated in the volar (palmar) hand/wrist. Its position is the intersections of the long axes of the four fingers while in a fist, or the base of the thenar eminence. When palpated in this position, the bone will be felt to slide forward during radial deviation (wrist abduction) and flexion.

Clicking of the scaphoid or no anterior translation can indicate scapholunate instability.

Etymology

editThe word scaphoid (Greek: σκαφοειδές) is derived from the Greek skaphos, which means "a boat", and the Greek eidos, which means "kind".[7] The name refers to the shape of the bone, supposedly reminiscent of a boat. In older literature about human anatomy,[4] the scaphoid is referred to as the navicular bone of the hand (this time from the Latin navis for boat); there is also a bone in a similar position in the foot, which is called the navicular. The modern term for the bone in the hand is scaphoid; in human anatomy the term navicular is reserved for the bone in the foot.

Additional images

edit-

Scaphoid bone of the left hand (shown in red). Animation.

-

Scaphoid bone of the left hand. Close up. Animation.

-

Scaphoid bone.

-

Scaphoid shown in yellow. Left hand. Palmar surface.

-

Scaphoid shown in yellow. Left hand. Dorsal surface.

-

Cross section of wrist (thumb on left). Scaphoid (labelled as "Navicular") shown in red.

-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection. Posterior view.

-

Scaphoid forms the radial (thumb-side) border of the carpal tunnel. Wrist joint. Deep dissection. Anterior (palmar) view.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i Beasley RW (2003). Beasley's Surgery of the Hand. New York: Thieme. ISBN 978-1-282-95002-3. OCLC 657589090.

- ^ Martini, Frederic; Tallitsch, Robert B.; Nath, Judi L. (2017). Human Anatomy (9th ed.). Pearson. p. 182. ISBN 9780134320762.

- ^ a b c d Eathorne SW (March 2005). "The wrist: clinical anatomy and physical examination--an update". Primary Care. 32 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2004.11.009. PMID 15831311.

- ^ a b c d Gray H (1918). "6b. The Hand. 1. The Carpus". Anatomy of the Human Body. 4 – via Bartleby.com.

- ^ a b Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AW (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Illustrated by Richard Tibbitts and Paul Richardson. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0. OCLC 646533128.

- ^ a b Wijetunga AR, Tsang VH, Giuffre B (March 2019). "The utility of cross-sectional imaging in the management of suspected scaphoid fractures". Journal of Medical Radiation Sciences. 66 (1): 30–37. doi:10.1002/jmrs.302. PMC 6399186. PMID 30160062.

- ^ Anderson K, Anderson LE, Glanze WD (1994). Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary (4th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1396. ISBN 978-0-8016-7225-5. OCLC 461378724.