Education in Belgium is regulated and for the most part financed by one of the three communities: Flemish, French and German-speaking. Each community has its own school system, with small differences among them. The federal government plays a very small role: it decides directly the age for mandatory schooling and indirectly the financing of the communities.

The schools can be divided in three groups (Dutch: netten; French: réseaux):

- Schools owned by the communities (GO! Onderwijs van de Vlaamse gemeenschap; Wallonie-Bruxelles Enseignement)

- Subsidized public schools (officieel gesubsidieerd onderwijs; réseau officiel subventionné), organized by provinces, municipalities or the Brussels French Community Commission

- Subsidized free schools (vrij gesubsidieerd onderwijs; réseau libre subventionné), mainly organized by an organization affiliated to the Catholic church

The latter is the largest group, both in number of schools and in number of pupils.

Education in Belgium is compulsory between the ages of 5 and 18 or until one graduates from secondary school.[1]

History

editIn the past there were conflicts between state schools and Catholic schools, and disputes regarding whether the latter should be funded by the government (see first and second School Wars). The 1958 School Pact was an agreement by the three large political parties to end these conflicts.

The 1981 state reform transferred some matters from the federal Belgian level to the communities. In 1988, the majority of educational matters were transferred. Nowadays, very few general matters are regulated on a national level. The current ministries for education are the Flemish Government, the Government of the French Community and the Government of the German-speaking Community for each community respectively. Brussels, being bilingual French-Dutch, has schools provided by both the Flemish and French-speaking community. Municipalities with language facilities often have schools provided by two communities (Dutch-French or German-French) as well.

Stages of education

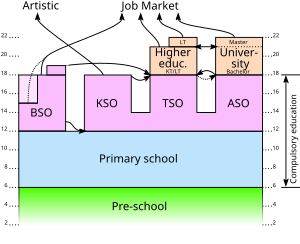

editThe different stages of education are the same in all communities:

- Fundamental education (Dutch: basisonderwijs; French: enseignement fondamental), consisting of

- Preschool education (kleuteronderwijs; enseignement maternel): –6 years

- Primary school (lager onderwijs; enseignement primaire): 6–12 years

- Secondary education (secundair onderwijs; enseignement secondaire): 12–18 years

- Higher education (hoger onderwijs; enseignement supérieur)

- University (universiteit; université)

- Polytechnic/Vocational university (hogeschool; haute école)

Pre-school

editFree pre-primary schooling (Dutch: kleuterschool; French: enseignement maternel; German: Kindergarten) is provided to every child from the age of 2 years 6 months. In most schools the child can start in school as soon as they reach this age, so class size for the youngest children grows during the year. In the Flemish region, start dates are limited to 6 per year, after a school holiday period and the first school day in February.

The aim of pre-school is to develop, in a playful way, children's cognitive skills, their capacity to express themselves and communicate, their creativity and independence. There are no formal lessons or assessments, and everything is taught through a framework of play.

Although it is not compulsory until the age of 5, more than 90% of all children in the age category attend pre-school.[2]

Most pre-schools are attached to a particular primary school. Preschools and primary schools often share buildings and other facilities. Some schools offer special pre-primary education for children with disabilities or other special needs.

Primary school

editPrimary school (Dutch: lager onderwijs; French: enseignement primaire; German: Grundschule) consists of six years and the subjects taught are generally the same at all schools. Primary schooling is free and age is the only entrance requirement.

Primary education is divided into three cycles (Dutch: graden; French: degrés):

- First cycle (year 1 and 2)

- Second cycle (year 3 and 4)

- Third cycle (year 5 and 6)

Education in primary schools is rather traditional: it concentrates on reading, writing and basic mathematics, but also touches already a very broad range of topics (biology, music, religion, history, etc.). School usually starts about 8:30 and finishes around 15:30. A lunch time break is usually provided from 12:00 to 13:30. Wednesday afternoon, Saturday and Sunday are free. While morning lessons often concentrate on reading, writing and basic mathematics, lessons in the afternoon are usually about other topics like biology, music, religion, history or "do it yourself" activities.

Flemish schools in Brussels and some municipalities near the language border, must offer French lessons starting from the first or the second year. Most other Flemish schools offer French education in the third cycle. Some of the latter schools offer non-mandatory French lessons already in the second cycle. Primary schools in the French Community must teach another language, which is generally Dutch or English, depending on the school. Primary schools in the German Community have obligatory French lessons.

There are also some private schools set up to serve various international communities in Belgium (e.g. children of seafarers or European diplomats), mainly around the larger cities. Some schools offer special primary education for children with disabilities or other special needs.

Secondary education

editWhen graduating from primary school around the age of 12, students enter secondary education. Here they have to choose a course that they want to follow, depending on their skill level and interests.

Secondary education consists of three cycles (Dutch: graden; French: degrés; German: Grad):

- First cycle (year 1 and 2)

- Second cycle (year 3 and 4)

- Third cycle (year 5 and 6)

The Belgian secondary education grants the pupils more choice as they enter a higher cycle. The first cycle provides a broad general basis, with only a few options to choose from (such as Latin, additional mathematics and technology). This should enable students to orient themselves in the most suitable way towards the many different courses available in the second and third stages. The second and third cycle are much more specific in each of the possible directions. While the youngest pupils may choose at the most two or four hours per week, the oldest pupils have the opportunity to choose between different "menus": like Mathematics and Science, Economics and Languages or Latin and Greek. They are then able to shape the largest part of the time they spend at school. However, some core lessons are compulsory like the first language and sport, etc. This mix between compulsory and optional lessons grouped in menus, makes it possible to keep class structures even for the oldest students.

Higher education

editHigher education in Belgium is organized by the two main communities, the Flemish Community and the French Community. German speakers typically enroll in institutions in the French Community or in Germany.

Types of institutions of higher education

editFlanders' higher education is separated between universities (5 universities, universiteiten) and university colleges (hogescholen). The French Community organises higher education in universities (6 universities), but makes a difference between the two types of schools that make up university colleges : Hautes écoles and Écoles supérieures des Arts (a limited number of artistic institutions allowed to process selection of incoming students).

Admission to universities and colleges

editIn Belgium anybody with a qualifying diploma of secondary education is free to enroll at any institute of higher education of their choosing. The 4 major exceptions to this rule are those wanting to pursue a degree in:

- Medicine/Dentistry

- prospective medicine or dentistry students must take an entrance exam organized by the government. This exam was introduced in the 1990s for the Flemish Community and in 2017 for the French Community of Belgium (where citizens of the German-speaking community can take their test in German), to control the influx of students. The exam assesses the student's knowledge of science, their ability to think in abstract terms (IQ test) and their psychological aptitude to become a physician.

- Arts

- entrance exams to arts programs, which are mainly of a practical nature, are organized by the colleges individually.

- Engineering Sciences

- leading to the degree of Master of Science, these faculties had a long-standing tradition of requiring an entrance exam (mainly focused on mathematics); the exam has now been abolished in the Flemish Community but is still organized in the French Community.

- Management Sciences

- Leading to a master's after master's degree (Flanders), specialisation master's degree (French Community) or a Master in Business Administration degree, these management schools organise admission tests that focus on individual motivation and pre-knowledge of a specialised domain. E.g. A Master in Financial Management programme requires prior knowledge on corporate finance and management control topics.

Cost of higher education

editThe registration fee for any university or college is fixed by the government of the French-speaking or the Dutch-speaking community, and indexed annually. There are three categories, depending on whether the student is eligible and applies for financial aid:

- Bursary-student

- A student who is receiving financial aid. In French-speaking institutions, their tuition is free; in Dutch-speaking institutions, their tuition fee is between €80 and €100.

- Almost-bursary student

- A student who is not eligible for financial aid but has a family income below €1286.09 per month. In Dutch-speaking institutions, their tuition fee is between €333.60 and €378.60.[3] and in French-speaking institutions, the fee must not exceed half of the full tuition fee.

- Non-bursary student

- Anyone not eligible for financial aid with an income above €1286.09 per month. In Dutch-speaking institutions their tuition fee is between €890,00 and €910,00.[3] and in French-speaking institutions, around €830.

The financial aid awarded by the community governments depends on the income of the student's family, and other familial circumstances, but is never more than approximately €5,000 per year. As a rule, the aid is not based on the student's results. However, students who fail too many classes may lose their financial aid.

Bologna changes

editPrior to the adoption of the Bologna process, the Belgian higher education system had the following degrees:

- Graduate degree (Dutch: gegradueerde, French: gradué): typically a 3-year-long programme at a college, with a vocational character, also called short type or one cycle higher education.

- Candidate degree (Dutch: kandidaat, French: candidat): the first 2 years at a university (3 years for medicine studies) or at some colleges offering long type or two cycle programs. This diploma had no finality than to give access to the licentiate studies.

- Licentiate diploma (Dutch: licentiaat, French: licencié): The second cycle, leading to a degree after typically 2 years (3 years for civil engineers or lawyers, 4 years for medicine).

- DEA (French:diplôme d'études approfondies) this is a 2 years postgraduate degree exists in the French speaker universities, the admission to this degree requires a Licentiate. the DEA is equivalent to the Master's degree in the American-English systems. [Note: The latter description is inaccurate. A DEA is a French (France) diploma and is not a recognized Belgian diploma. A Licentiate degree is customarily considered to be the equivalent of the French (France) maîtrise. Pre-Bologna Licenciate diplomas are also considered to be a close equivalent to an American-English master's degree: they require 2 to 3 years of advanced coursework in the study area and they may require the production of a final, substantial written thesis based on original research in the area of study (Dutch: eindscriptie, French:mémoire de licence)].

A university education was not considered finished until the licentiate diploma is obtained. Occasionally it was possible to switch specializations after obtaining the candidate diploma. For example, a student with a mathematics candidate diploma was often allowed to start in the third year of computer science class. Sometimes a graduate diploma was also accepted as an equivalent to a candidate diploma (with additional courses if necessary), allowing for 2 or 3 more years of education at a university.

Since the adoption of the Bologna process in most European countries, the higher education system in Belgium follows the Bachelor/Master system:

- Bachelor's degree (French: bachelier; Dutch: bachelor)

- delivered after 3 years (180 ECTS) of Bachelor's studies (French: baccalauréat; Dutch: bacheloropleiding). Distinction is to be made between:

- the professional bachelor, (French: bachelier professionnel delivered after a formation de type court; Dutch: professionele bachelor) issued only by university colleges, which replaces the former graduate degree and which has a finality.

- the academic bachelor, (French: bachelier académique; Dutch: academische bachelor) issued by universities and some university colleges, which replaces the candidate degree and gives access to master's studies.

- So-called Banaba (Flemish Community) or Bachelier de spécialisation (French Community), specialisation degrees offered after a professional bachelor's degree.

- Master's degree

- delivered after 1 or 2 years (60 or 120 ECTS) of Master's studies. Manama's (Flemish Community) or Masters de spécialisation (French Community) exist in universities and are specialisation degrees offered after a master's degree.

After obtaining a master's degree, talented students can pursue research projects leading to a doctorate degree. PhDs are only awarded by universities, but theses can be written at university colleges or art schools, in collaboration with and published by a university.

Quality

editIn the 2003 PISA-study[4] of secondary school students by the OECD, the Belgian students scored relatively highly. The results of the Dutch-speaking students were significantly higher than the scores of the German-speaking students which were in turn significantly higher than the French-speaking students.[5]

The United Nations Education Index, which is measured by the adult literacy rate and the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrolment ratio, ranks Belgium on the 18th place in the world as of 2011. A 2007 study found that violence experienced by teachers in francophone Belgium was a significant factor in decisions to leave the teaching profession.[6]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ (Dutch) Leerplicht

- ^ Structures of education, vocational training and adult education systems in Europe, National Foundation for Educational Research, 2003, archived from the original on January 19, 2008

- ^ a b "Home".

- ^ Learning for Tomorrows World – First Results from PISA 2003 (PDF), OECD, 2004

- ^ Learning for Tomorrows World – First Results from PISA 2003 (PDF), Universiteit Gent, 2005

- ^ Galand, B.; Lecocq, C.; Philipott, P. (2007). "School violence and teacher professional disengagement". British Journal of Educational Psychology. 77 (Pt 2): 465–477. doi:10.1348/000709906X114571. PMID 17504557.

Further reading

edit- Passow, A. Harry et al. The National Case Study: An Empirical Comparative Study of Twenty-One Educational Systems. (1976) online

External links

edit- (in Dutch) Vlaams Ministerie van Onderwijs (English information) – Flemish Ministry of Education

- Higher Education Register: recognised programmes and institutions in Flanders

- (in French) L'enseignement en Communauté Française – Education in the French Community

- (in German) Unterrichtswesen – Ministry of Education of the German Community in Belgium

- Studying in Belgium at Federal Public Service Foreign Affairs

- The information network on education in Europa – Contains documents with much information on education systems in Belgium

- Information on education in Belgium, OECD – Contains indicators and information about Belgium and how it compares to other OECD and non-OECD countries

- Diagram of Belgian education systems, OECD – Using 1997 ISCED classification of programmes and typical ages. Also in French and Dutch