This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

A projection screen is an installation consisting of a surface and a support structure used for displaying a projected image for the view of an audience. Projection screens may be permanently installed on a wall, as in a movie theater, mounted to or placed in a ceiling using a rollable projection surface that retracts into a casing (these can be motorized or manually operated), painted on a wall,[1] or portable with tripod or floor rising models as in a conference room or other non-dedicated viewing space. Another popular type of portable screens are inflatable screens for outdoor movie screening (open-air cinema).[2]

Uniformly white or grey screens are used almost exclusively as to avoid any discoloration to the image, while the most desired brightness of the screen depends on a number of variables, such as the ambient light level and the luminous power of the image source. Flat or curved screens may be used depending on the optics used to project the image and the desired geometrical accuracy of the image production, flat screens being the more common of the two. Screens can be further designed for front or back projection, the more common being front projection systems, which have the image source situated on the same side of the screen as the audience.

Different markets exist for screens targeted for use with digital projectors, movie projectors, overhead projectors and slide projectors, although the basic idea for each of them is very much the same: front projection screens work on diffusely reflecting the light projected on to them, whereas back-projection screens work by diffusely transmitting the light through them.

Screens by installation type in different settings

editIn the commercial movie theaters, the screen is a reflective surface that may be either aluminized (for high contrast in moderate ambient light) or a white surface with small glass beads (for high brilliance under dark conditions). The screen also has hundreds of small, evenly spaced holes to allow air to and from the speakers and subwoofer, which often are directly behind it.

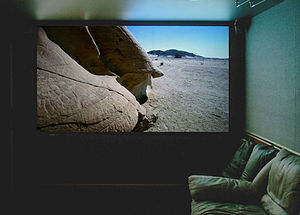

Rigid wall-mounted screens maintain their geometry perfectly which makes them suitable for applications that demand exact reproduction of image geometry. Such screens are often used in home theaters, along with the pull-down screens.

Pull-down screens (also known as manual wall screens) are often used in spaces where a permanently installed screen would require too much space. These commonly use painted fabric that is rolled in the screen case when not used, making them less obtrusive when the screen is not in use.

Fixed-frame screens provide the greatest level of uniform tension on the screens surface, resulting in the optimal image quality. They are often used in home theater and professional environments where the screen does not need to be recessed into the case.

Electric screens can be wall-mounted, ceiling-mounted or ceiling recessed. These are often larger screens, though electric screens are available for home theater use as well. Electric screens are similar to pull-down screens, but instead of the screen being pulled down manually, an electric motor raises and lowers the screen. Electric screens are usually raised or lowered using either a remote control or wall-mounted switch, although some projectors are equipped with an interface that connects to the screen and automatically lowers the screen when the projector is switched on and raises it when the projector is switched off.

Switchable projection screens can be switched between opaque and clear. In the opaque state, projected image on the screen can be viewed from both sides. It is very good for advertising on store windows.

Mobile screens usually use either a pull-down screen on a free stand, or pull up from a weighted base. These can be used when it is impossible or impractical to mount the screen to a wall or a ceiling.

Both mobile and permanently installed pull-down screens may be of tensioned or not tensioned variety. Tensioned models attempt to keep the fabric flat and immobile, whereas the not tensioned models have the fabric of the screen hanging freely from their support structures. In the latter screens, the fabric can rarely stay immobile if there are currents of air in the room, giving imperfections to the projected image.

Specialty screens may not fall into any of these categories. These include non-solid screens, inflatable screens and others, and can be inexpensively made at home. See the respective articles for more information.

Screen gain

editOne of the most often quoted properties in a home theater screen is the gain. This is a measure of reflectivity of light compared to a screen coated with magnesium carbonate, titanium dioxide,[3] or barium sulfate when the measurement is taken for light targeted and reflected perpendicular to the screen. Titanium dioxide is a bright white colour, but greater gains can be accomplished with materials that reflect more of the light parallel to projection axis and less off-axis.

Frequently quoted gain levels of various materials range from 0.8 of light grey matte screens to 2.5 of the more highly reflective glass bead screens. Very high gain levels could be attained simply by using a mirror surface, although the audience would then just see a reflection of the projector, defeating the purpose of using a screen. Many screens with higher gain are simply semi-glossy, and so exhibit more mirror-like properties, namely a bright "hot spot" in the screen—an enlarged (and greatly blurred) reflection of the projector's lens. Opinions differ as to when this "hot spotting" begins to be distracting, but most viewers do not notice differences as large as 30% in the image luminosity, unless presented with a test image and asked to look for variations in brightness. This is possible because humans have greater sensitivity to contrast in smaller details, but less so in luminosity variations as great as half of the screen. Other screens with higher gain are semi-retroreflective. Unlike mirrors, retroreflective surfaces reflect light back toward the source. Hot spotting is less of a problem with retroreflective high-gain screens. At the perpendicular direction used for gain measurement, mirror reflection and retroreflection are indistinguishable, and this has sown confusion about the behavior of high gain screens.

A second common confusion about screen gain arises for grey-colored screens. If a screen material looks grey on casual examination then its total reflectance is much less than 1. However, the grey screen can have measured gain of 1 or even much greater than 1. The geometric behavior of a grey screen is different from that of a white screen of identical gain. Therefore, since geometry is important in screen applications, screen materials should be at least specified by their gain and their total reflectance. Instead of total reflectance, "geometric gain" (equal to the gain divided by the total reflectance) can be the second specification.

Curved screens can be made highly reflective without introducing any visible hot spots, if the curvature of the screen, placement of the projector and the seating arrangement are designed correctly. The object of this design is to have the screen reflect the projected light back to the audience, effectively making the entire screen a giant "hot spot". If the angle of reflection is about the same across the screen, no distracting artifacts will be formed.

Semi-specular high gain screen materials are suited to ceiling-mounted projector setups since the greatest intensity of light will be reflected downward toward the audience at an angle equal and opposite to the angle of incidence. However, for a viewer seated to one side of the audience the opposite side of the screen is much darkened for the same reason. Some structured screen materials are semi-specularly reflective in the vertical plane while more perfectly diffusely reflective in the horizontal plane to avoid this. Glass-bead screens exhibit a phenomenon of retroreflection; the light is reflected more intensely back to its source than in any other direction. They work best for setups where the image source is placed in the same direction from the screen as the audience. With retroreflective screens, the screen center might be brighter than the screen periphery, a kind of hot spotting. This differs from semi-specular screens where the hot spot's location varies depending on the viewer's position in the audience. Retroreflective screens are seen as desirable due to the high image intensity they can produce with a given luminous flux from a projector.

Screen geometry

editProjector screens are almost always rectangular in shape. They typically follow a standard display aspect ratio. For most home cinema setups there are two aspect ratios. 16:9 and Cinemascope.[4]

For classroom, businesses and houses of worship settings, 16:10 is the more commonly used projector screen aspect ratio because this matches the aspect ratio used by many modern computers.[5]

Square-shaped screens used for overhead projectors sometimes double as projection screens for digital projectors in meeting rooms, where space is scarce and multiple screens can seem redundant. These screens have an aspect ratio of 1:1 by definition.

Most image sources are designed to project a perfectly rectangular image on a flat screen. If the audience stays relatively close to the projector, a curved screen may be used instead without visible distortion in the image geometry. Viewers closer or farther away will see a pincushion or barrel distortion, and the curved nature of the screen will become apparent when viewed off-axis.

Image brightness and contrast

editApparent contrast in a projected image — the range of brightness — is dependent on the ambient light conditions, luminous power of the projector and the size of the image being projected. A larger screen size means less luminous (luminous power per unit solid angle per unit area) and thus less contrast in the presence of ambient light. Some light will always be created in the room when an image is projected, increasing the ambient light level and thus contributing to the degradation of picture quality. This effect can be lessened by decorating the room with dark colours. The real-room situation is different from the contrast ratios advertised by projector manufacturers, who record the light levels with projector on full black / full white, giving as high contrast ratios as possible.

Manufacturers of home theater screens have attempted to resolve the issue of ambient light by introducing screen surfaces that direct more of the light back to the light source. The rationale behind this approach relies on having the image source placed near the audience, so that the audience will actually see the increased reflected light level on the screen.

Highly reflective flat screens tend to suffer from hot spots, when part of the screen seems much more bright than the rest. This is a result of the high directionality (mirror-likeness) of such screens. Screens with high gain also have a narrower usable viewing angle, as the amount of reflected light rapidly decreases as the viewer moves away from front of such screen. Because of the said effect, these screens are also less vulnerable to ambient light coming from the sides of the screen, as well.

Grey screens

editA relatively recent attempt in improving the perceived image quality is the introduction of grey screens, which are more capable of darker tones than their white counterparts. A matte grey screen would have no advantage over a matte white screen in terms of contrast; contemporary grey screens are rather designed to have a gain factor similar to those of matte white screens, but a darker appearance. A darker (grey) screen reflects less light, of course—both light from the projector and ambient light. This decreases the luminance (brightness) of both the projected image and ambient light, so while the light areas of the projected image are dimmer, the dark areas are darker; white is less bright, but intended black is closer to actual black. Many screen manufacturers thus appropriately call their grey screens "high-contrast" models.

Although a projection screen cannot improve a projector's contrast level, the perceived contrast can be boosted.

In an optimal viewing room, the projection screen is reflective, whereas the surroundings are not. The ambient light level is related to the overall reflectivity of the screen, as well as that of the surroundings. In cases where the area of the screen is large compared to that of the surroundings, the screen's contribution to the ambient light may dominate and the effect of the non-screen surfaces of the room may even be negligible. Some examples of this are planetariums and virtual-reality cubes featuring front-projection technology. Some planetariums with dome-shaped projection screens have thus opted to paint the dome interior in gray, in order to reduce the degrading effect of inter-reflections when images of the sun are displayed simultaneously with images of dimmer objects.

Grey screens are designed to rely on powerful image sources that are able to produce adequate levels of luminosity so that the white areas of the image still appear as white, taking advantage of the non-linear perception of brightness in the human eye. People may perceive a wide range of luminosities as "white", as long as the visual clues present in the environment suggest such an interpretation. A grey screen may thus succeed almost as well in delivering a bright-looking image, or fail to do so in other circumstances.

Compared to a white screen, a grey screen reflects less light to the room and less light from the room, making it increasingly effective in dealing with the light originating from the projector. Ambient light originating from other sources may reach the eye immediately after having reflected from the screen surface, giving no advantage over a white high-gain screen in terms of contrast ratio. The potential improvement from a grey screen may thus be best realized in a darkened room, where the only light is that of the projector.

Partly fueled by popularity, grey screen technology has improved greatly in recent years. Grey screens are now available in various gain and grey-scale levels.

Selectively reflective screens

editCertain screens are claimed to selectively reflect the narrow wavelengths of projector light while absorbing other wavelengths in the optical spectrum. Sony makes a screen [6] that appears grey in normal room light, and is intended to reduce the effect of ambient light.[7] This is purported to work by preferentially absorbing ambient light of colors not used by the projector, while preferentially reflecting the colors of red, green and blue light the projector uses.[8] A true color-selective screen has not been substantiated. A contrast-enhancing screen has been introduced by Dai Nippon Printing (DNP) and Screen Innovations that is based on thin layers of black louvers rather than wavelength-selective reflection properties.[9]

Screens as an optical element

editIn an optimally configured system, projection screen surface and the real image plane are made to coincide. From an optical point of view, a screen is not needed for the image to form; screens are rather used to make an image visible.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Acrylic paint used to make a movie screen on the wall Archived 2007-02-24 at the Wayback Machine (see screen goo)

- ^ "Projector Screen Buying Guide". ProjectorScreen.com. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Projector Central [1] Screen gain

- ^ "How To Design A Home Theater". ProjectorScreen.com. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Knight, Daniel. "With 10% of the US Notebook Market, Where Will Apple Go Next?". Lowendmac.com. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Seán Byrne. Sony introduces black projector screen for well-lit up areas. June 24, 2004.

- ^ Gizmodo. Picture of Sony's Black Backed Projection Screen Archived 2006-05-23 at the Wayback Machine. June 29, 2004.

- ^ Gizmodo. Sony's high contrast screen Archived 2006-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ray Adkins. Screen Innovations Visage Review