Chondrus crispus—commonly called Irish moss or carrageenan moss (Irish carraigín, "little rock")—is a species of red algae which grows abundantly along the rocky parts of the Atlantic coasts of Europe and North America. In its fresh condition it is soft and cartilaginous, varying in color from a greenish-yellow, through red, to a dark purple or purplish-brown. The principal constituent is a mucilaginous body, made of the polysaccharide carrageenan, which constitutes 55% of its dry weight. The organism also consists of nearly 10% dry weight protein and about 15% dry weight mineral matter, and is rich in iodine and sulfur. When softened in water it has a sea-like odour. Because of the abundant cell wall polysaccharides, it will form a jelly when boiled, containing from 20 to 100 times its weight of water.

| Irish moss | |

|---|---|

| |

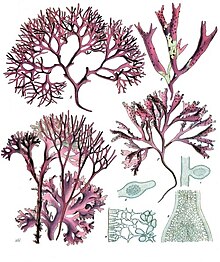

| A-D Chondrus crispus ; E-F Mastocarpus stellatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | Archaeplastida |

| Division: | Rhodophyta |

| Class: | Florideophyceae |

| Order: | Gigartinales |

| Family: | Gigartinaceae |

| Genus: | Chondrus |

| Species: | C. crispus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chondrus crispus | |

Description

editChondrus crispus is a relatively small sea alga, reaching up to a little more than 20 cm in length. It grows from a discoid holdfast and branches four or five times in a dichotomous, fan-like manner. The morphology is highly variable, especially the broadness of the thalli. The branches are 2–15 mm broad and firm in texture, and the color ranges from bright green towards the surface of the water, to deep red at greater depths.[1] The gametophytes (see below) often show a blue iridescence at the tip of the fronds[2] and fertile sporophytes show a spotty pattern. Mastocarpus stellatus (Stackhouse) Guiry is a similar species which can be readily distinguished by its strongly channelled and often somewhat twisted thalli.

Distribution

editChondrus crispus is common all around the shores of Ireland and can also be found along the coast of Europe including Iceland, the Faroe Islands,[3] western Baltic Sea to southern Spain.[4] It is found on the Atlantic coasts of Canada[4][5] and recorded from California in the United States to Japan.[4] However, any distribution outside the Northern Atlantic needs to be verified. There are also other species of the same genus in the Pacific Ocean, for example, C. ocellatus Holmes, C. nipponicus Yendo, C. yendoi Yamada et Mikami, C. pinnulatus (Harvey) Okamura and C. armatus (Harvey) Yamada et Mikami.[6]

Ecology

editChondrus crispus is found growing on rock from the middle intertidal zone into the subtidal zone,[7] all the way to the ocean floor. It is able to survive with minimal sunlight.

C. crispus is susceptible to infection from the oomycete Pythium porphyrae.[8][9]

Uses

editC. crispus is an industrial source of carrageenan commonly used as a thickener and stabilizer in milk products, such as ice cream and processed foods.[10] In Europe, it is indicated as E407 or E407a. It may also be used as a thickener in calico printing and paper marbling, and for fining beer.[10][11] Irish moss is frequently used with Mastocarpus stellatus (Gigartina mamillosa), Chondracanthus acicularis (G. acicularis), and other seaweeds, which are all commonly found growing together. Carrageenan may be extracted from tropical seaweeds of the genera Kappaphycus and Eucheuma.[12]

Life history

editIrish moss undergoes an alternation of generation lifecycle common in many species of algae (see figure below). The two distinct stages are the sexual haploid gametophyte stage and the asexual diploid sporophyte stage. In addition, a third stage - the carposporophyte - is formed on the female gametophyte after fertilization. The male and female gametophytes produce gametes which fuse to form a diploid carposporophyte, which forms carpospores, which develops into the sporophyte. The sporophyte then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid tetraspores (which can be male or female) that develop into gametophytes. The three stages (male, female, and sporophyte) are difficult to distinguish when they are not fertile; however, the gametophytes often show a blue iridescence.

Scientific interest

edit| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 205 kJ (49 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

12.29 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 0.61 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 1.3 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.16 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.51 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[13] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[14] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

C. crispus, compared to most other seaweeds, is well-investigated scientifically. It has been used as a model species to study photosynthesis, carrageenan biosynthesis, and stress responses. The nuclear genome was sequenced in 2013.[15] The genome size is 105 Mbp and is coding for 9,606 genes. It is characterised by relatively few genes with very few introns. The genes are clustered together, with normally short distances between genes and then large distances between groups of genes.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Sadava, David; Heller, Craig; Orians, Gordon; Purves, Bill; Hillis, David (2008). Life: The Science of Biology (8th ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. p. 601. ISBN 9780716776710.

- ^ Chandler, Chris J.; Wilts, Bodo D.; Vignolini, Silvia; Brodie, Juliet; Steiner, Ullrich; Rudall, Paula J.; Glover, Beverley J.; Gregory, Thomas; Walker, Rachel H. (3 July 2015). "Structural colour in Chondrus crispus". Scientific Reports. 5: 11645. Bibcode:2015NatSR...511645C. doi:10.1038/srep11645. PMC 5155586. PMID 26139470.

- ^ F. Börgesen (1903). "Marine Algae of the Faröes". Botany of the Faröes based upon Danish investigations Part II (Copenhagen Reprint 1970). Linnaeus Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-90-6105-011-7.

- ^ a b c P. S. Dixon & L. M. Irvine (1977). Seaweeds of the British Isles. Vol. 1 Rhodophyta Part 1: Introduction, Nemaliales, Gigartinales. British Museum (Natural History) London. ISBN 978-0-565-00781-2.

- ^ W. R. Taylor (1972). Marine Algae of the Northeastern Coast of North America. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. ISBN 978-0-472-04904-2.

- ^ Hu, Z., Critchley, A.T., Gao T, Zeng X, Morrell, S.L. and Delin, D. 2007 Delineation of Chondrus (Gigartinales, Florideophyceae) in China and the origin of C. crisps inferred from molecular data. Marine Biology Research, 3: 145-154

- ^ Morton, O. 1994. Marine Algae of Northern Ireland. Ulster Museum ISBN 0 900761 28 8

- ^ Diehl, Nora; Kim, Gwang Hoon; Zuccarello, Giuseppe C. (March 2017). "A pathogen of New Zealand Pyropia plicata (Bangiales, Rhodophyta), Pythium porphyrae (Oomycota)". Algae. 32 (1): 29–39. doi:10.4490/algae.2017.32.2.25.

- ^ LéVesque, C.André; De Cock, Arthur W.A.M. (December 2004). "Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Pythium". Mycological Research. 108 (12): 1363–1383. doi:10.1017/S0953756204001431. ISSN 0953-7562. OCLC 358362888. PMID 15757173. S2CID 20561417.

- ^ a b "Carageenan". PubChem, US National Library of Medicine. 9 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 795.

- ^ Bixler, H. J.; Porse, H. (2011). "A decade of change in the seaweed hydrocolloids industry". Journal of Applied Phycology. 23 (3): 321–335. doi:10.1007/s10811-010-9529-3. S2CID 24607698.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ Collén, J; et al. (2013). "Genome structure and metabolic features in the red seaweed Chondrus crispus shed light on evolution of the Archaeplastida". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (13): 5247–5252. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.5247C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221259110. PMC 3612618. PMID 23503846.

External links

edit- AlgaeBase: Chondrus crispus

- Chondrus crispus Stackhouse Chondrus crispus.

- Marine Life Information Network

- Irish Moss industry on Prince Edward Island [1]

- Sea Moss Market Report