Vortioxetine, sold under the brand name Trintellix (in the US) and Brintellix (in the EU) among others, is an antidepressant of the serotonin modulator and stimulator (SMS) class.[15][3] Its effectiveness is viewed as similar to that of other antidepressants.[15] It is taken orally.[15]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /vɔːrtiˈɒksətiːn/ vor-tee-OK-sə-teen |

| Trade names | Trintellix, Brintellix, others |

| Other names | Lu AA21004, Vortioxetine hydrobromide (JAN JP), Vortioxetine hydrobromide (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a614003 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Serotonin modulator and stimulator (SMS)[3] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 75% (peak at 7–11 hours)[13] |

| Protein binding | 98–99%[13][11][14] |

| Metabolism | Liver, primarily CYP2D6-mediated oxidation[13] |

| Elimination half-life | 66 hours[13] |

| Excretion | 59% in urine, 26% in feces[13] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.258.748 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H22N2S |

| Molar mass | 298.45 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include nausea, dry mouth, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, and sexual dysfunction.[15][11] Serious side effects may include suicide in those under the age of 25, serotonin syndrome, bleeding, mania, and SIADH.[15] A withdrawal syndrome may occur if the medication is abruptly stopped or the dose is decreased.[15] Use during pregnancy and breastfeeding is not generally recommended.[16] Vortioxetine's mechanism of action is not entirely understood but is believed to be related to increasing serotonin levels and possibly interacting with certain serotonin receptors.[15][17][18]

It was approved for medical use in the United States in 2013.[15][19] In 2020, it was the 243rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[20][21]

Medical uses

editVortioxetine is utilized as a treatment for major depressive disorder,[15] with its effectiveness shown to be similar to other antidepressants[15][22][23] and its effect size has been described as modest.[24] Vortioxetine may be used when other treatments have failed.[11][25][26][27] A 2017 Cochrane review on vortioxetine determined that its place in the treatment of severe depression is unclear due to low-quality evidence and that more studies comparing vortioxetine to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the typical first-line treatments, are needed.[28] Vortioxetine appears to work in depressed patients with anxiety.[29]

Vortioxetine is also used off-label for anxiety.[30] A 2016 review found it was not useful in generalized anxiety disorder at 2.5, 5, and 10 mg doses (15 and 20 mg doses were not tested).[31] A 2019 meta-analysis found that vortioxetine did not produce statistically significant results over placebo in the symptoms, quality of life, and remission rates of generalized anxiety disorder, but it was well-tolerated.[32] However, a 2018 meta-analysis supported use and efficacy of vortioxetine for generalized anxiety disorder, though stated that more research was necessary to strengthen the evidence.[33] A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that there was uncertainty about the effectiveness of vortioxetine for anxiety due to existing evidence being of very low-quality.[34] In a 2020 network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, vortioxetine was among the lowest remission rates for generalized anxiety disorder of the included medications (odds ratio = 1.30 for vortioxetine, range of odds ratios for other agents = 1.13–2.70).[35]

Contraindications

editVortioxetine is contraindicated in those taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), due to the possibility of serotonin syndrome.[11]

Adverse effects

edit| Side effect | Placebo | Vortioxetine | Duloxetine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg/day | 10 mg/day | 15 mg/day | 20 mg/day | 60 mg/day | ||

| Any | 62% | 66% | 67% | 70% | 73% | 77% |

| Nausea | 9% | 21% | 26% | 32% | 32% | 36% |

| Vomiting | 1% | 3% | 5% | 6% | 6% | 4% |

| Diarrhea | 6% | 7% | 7% | 10% | 7% | ? |

| Constipation | 3% | 3% | 5% | 6% | 6% | 10% |

| Dry mouth | 6% | 7% | 7% | 6% | 8% | ? |

| Flatulence | 1% | 1% | 3% | 2% | 1% | ? |

| Dizziness | 6% | 6% | 6% | 8% | 9% | ? |

| Abnormal dreams | 1% | <1% | <1% | 2% | 3% | ? |

| Itching | 1% | 1% | 2% | 3% | 3% | ? |

| Notes: Vortioxetine and duloxetine (an SNRI) were directly compared in randomized clinical trials. Other reported side effects of vortioxetine in clinical trials included headache, nasal symptoms, somnolence, and excessive sweating.[38][37] | ||||||

The most common side effects reported with vortioxetine are nausea, vomiting, constipation, and sexual dysfunction, among others.[11] With the exceptions of nausea and sexual dysfunction, these side effects were reported by less than or equal to 10% of study participants given vortioxetine.[11][38] Significant percentages of placebo-treated participants also report these side effects.[11][38] Discontinuation of treatment due to adverse effects in clinical trials was 8% with vortioxetine versus 3% with placebo.[38]

Sexual dysfunction, such as decreased libido, abnormal orgasm, delayed ejaculation, and erectile dysfunction, are well-known side effects of SSRIs and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).[18] In clinical trials, sexual dysfunction occurred more often with vortioxetine than with placebo and appeared to be dose-dependent.[18][17] Incidence of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction as measured with the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX) were 14 to 20% for placebo and 16 to 34% for vortioxetine over a dosage range of 5 to 20 mg/day.[18][17] The incidence of sexual dysfunction with vortioxetine was similar to that with the SNRI duloxetine, which had an incidence of 26 to 28% at the used dosage of 60 mg/day.[18] However, treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction caused by a prior SSRI was better improved by switching to vortioxetine than by switching to the SSRI escitalopram.[11] In another study, vortioxetine at a dosage of 10 mg/day though not at 20 mg/day produced less sexual dysfunction than the SSRI paroxetine.[11] These findings suggest that although vortioxetine can still cause sexual dysfunction itself, it may cause somewhat less sexual dysfunction than SSRIs and might be a useful alternative option for people experiencing sexual dysfunction with these medications.[11][39] The rates of voluntarily or spontaneously reported sexual dysfunction with vortioxetine are much lower than with the ASEX, ranging from <1 to 5% for vortioxetine versus <1 to 2% for placebo in clinical trials.[17][18][11]

| Quantification method | Group | Placebo | Vortioxetine | Duloxetine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg/day | 10 mg/day | 15 mg/day | 20 mg/day | 60 mg/day | |||

| Measured by ASEX | Men | 14% | 16% | 20% | 19% | 29% | 26% |

| Women | 20% | 22% | 23% | 33% | 34% | 28% | |

| Spontaneously reported | Men | 2% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 5% | ? |

| Women | <1% | <1% | 1% | <1% | 2% | ? | |

| Notes: Vortioxetine and duloxetine (an SNRI) were directly compared in randomized clinical trials. | |||||||

Significant changes in body weight (gain or loss) were not observed with vortioxetine in clinical trials.[11][38] However reports have come in from users regarding weight gain/loss since the approval of Vortioxetine.

Based on preliminary clinical studies, vortioxetine may cause less emotional blunting than SSRIs and SNRIs.[40][41]

If vortioxetine is used in combination with other serotonergic drugs like MAOIs or SSRIs, this may result in serotonin syndrome.[11]

Interactions

editVortioxetine is metabolized primarily by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2D6.[13] Inhibitors and inducers of CYP2D6 may modify the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine and necessitate dosage adjustments.[13]

Bupropion, a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor, has been found to increase peak levels of vortioxetine by 2.1-fold and total vortioxetine levels by 2.3-fold (bupropion dosed at 300 mg/day and vortioxetine dosed at 10 mg/day).[13] The incidence of side effects with vortioxetine, like nausea, headache, vomiting, and insomnia, was correspondingly increased with the combination.[13] Other strong CYP2D6 inhibitors, like fluoxetine, paroxetine, and quinidine, may have similar influences on the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine, and it is recommended that the dosage of vortioxetine be reduced by half when it is administered in combination with such medications.[13][11] Lesser interactions have additionally been identified for vortioxetine with the cytochrome P450 inhibitors ketoconazole and fluconazole.[13]

Rifampicin, a strong and broad cytochrome P450 inducer (though notably not of CYP2D6), has been found to decrease peak levels of vortioxetine by 51% and total levels of vortioxetine by 72% (rifampicin dosed at 600 mg/day and vortioxetine at 20 mg/day).[13] Similar influences on vortioxetine pharmacokinetics may also occur with other strong cytochrome P450 inducers like carbamazepine and phenytoin.[13] As such, it is recommended that increasing vortioxetine dosage be considered when it is given in combination with strong cytochrome P450 inducers.[13] The maximum recommended dose should not exceed three times the original vortioxetine dose.[13][11]

Vortioxetine and its metabolites show no meaningful interactions with a variety of assessed cytochrome P450 enzymes and transporters (e.g., P-glycoprotein) and hence vortioxetine is not expected to importantly influence the pharmacokinetics of other medications.[11][13]

The combination of vortioxetine with MAOIs, including other MAOIs like linezolid and intravenous methylene blue, may cause serotonin syndrome and is contraindicated.[11] The risk of serotonin syndrome may also be increased when vortioxetine is combined with other serotonergic drugs, like SSRIs, SNRIs, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), triptans, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, St John's wort, fentanyl, and lithium, among others.[11] However, vortioxetine is not considered to be contraindicated with serotonergic medications besides MAOIs.[11]

Pharmacology

editPharmacodynamics

edit| Target | Affinity | Functional activity | Action | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (nM) | IC50 / EC50 (nM) | IA (%) | ||

| SERT | 1.6 | 5.4 | – | Inhibition |

| NET | 113 | – | – | Inhibition |

| 5-HT1A | 15 | 200 | 96 | Agonist |

| 5-HT1B | 33 | 120 | 55 | Partial agonist |

| 5-HT1D | 54 | 370 | – | Antagonist |

| 5-HT2C | 180 | – | – | – |

| 5-HT3A | 3.7 | 12 | – | Antagonist |

| 5-HT7 | 19 | 450 | – | Antagonist |

| β1-adr. | 46 | – | – | Antagonist |

| Note: No significant activities at 70 other molecular targets (>1,000 nM) (including, e.g., the DAT). Sources: [42][43] | ||||

Vortioxetine increases serotonin concentrations in the brain by inhibiting its reuptake in the synapse, and also modulates (activates or blocks) certain serotonin receptors. This puts it in the class of serotonin modulators and stimulators, which also includes vilazodone.[44] More specifically, vortioxetine is a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, agonist of the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor, partial agonist of the 5-HT1B receptor, and antagonist of the serotonin 5-HT1D, 5-HT3, and 5-HT7 receptors, as well as an apparent ligand of the β1-adrenergic receptor.[45][43][42] In terms of functional activity however, vortioxetine appears to be much more potent on serotonin reuptake inhibition and 5-HT3 receptor antagonism than for its interactions with the other serotonin receptors.[45] Whereas vortioxetine has IC50 or EC50 values of 5.4 nM for the SERT and 12 nM for the 5-HT3 receptor, its values are 120 to 450 nM for the 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT7 receptors.[45] This translates to about 22- to 83-fold selectivity for SERT inhibition and 10- to 38-fold selectivity for 5-HT3 antagonism over activities at the other serotonin receptors.[45] 5-HT3 antagonism appears to have a better effect on REM sleep compared to paroxetine.[46]

It has been claimed that the serotonin transporter (SERT) and 5-HT3 receptor may be primarily occupied at lower clinical doses of vortioxetine and that the 5-HT1B, 5-HT1A, and 5-HT7 receptors may additionally be occupied at higher doses.[45] Occupancy of the serotonin transporter with vortioxetine in young men was found to be highest in the raphe nucleus with median occupancies of 25%, 53%, and 98% after 9 days of administration with 2.5, 10, and 60 mg/day vortioxetine.[13][47] In another study, serotonin transporter occupancy in men was 50%, 65%, and ≥80% for 5, 10, and 20 mg/day vortioxetine.[13][11]

Vortioxetine at 5 mg/day may produce antidepressant effects and result in SERT occupancy as low as 50%.[13][45][48] This is in apparent contrast to SSRIs and SNRIs, which appear to require a minimum of 70 to 80% occupancy for antidepressant efficacy.[13][45][49] These findings are suggestive that the antidepressant effects of vortioxetine may be mediated by serotonin receptor interactions in addition to serotonin reuptake inhibition.[13][45] A study found no significant occupancy of the 5-HT1A receptor with vortioxetine at 30 mg/day for 9 days, which suggests that at least this specific serotonin receptor may not be involved in the clinical pharmacology of vortioxetine.[45][14][47] However, methodological concerns were noted that may limit the interpretability of this result.[45][47][14] Occupancy of other serotonin receptors like 5-HT3 and 5-HT7 by vortioxetine in humans does not seem to have been studied.[18][45] In relation to the preceding, the contribution of serotonin receptor interactions to the antidepressant effects of vortioxetine is unknown and remains to be established.[13][11][18][17] Uncertainties remain about whether vortioxetine is indeed a clinically multimodal antidepressant or whether it is effectively "[just] another selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor".[17][18]

Antagonism of the 5-HT3 receptor has been found to enhance the increase in brain serotonin levels produced by serotonin reuptake inhibition in animal studies.[45][14] Whether or not the 5-HT3 receptor antagonism of vortioxetine likewise does this in humans or contributes to its clinical antidepressant efficacy is unclear.[17][18] SSRIs and 5-HT1A receptor agonists often produce nausea as a side effect, whereas 5-HT3 receptor antagonists like ondansetron are antiemetics and have been found to be effective in treating SSRI-induced nausea.[45] It was thought that the 5-HT3 receptor antagonism of vortioxetine would reduce the incidence of nausea relative to SSRIs.[45] However, clinical trials found significant and dose-dependent rates of nausea with vortioxetine that appeared to be comparable to those found with the SNRI duloxetine.[11][18]

Pharmacokinetics

editVortioxetine is well-absorbed when taken orally and has an oral bioavailability of 75%.[13] It is systemically detectable after a single oral dose by 0.781 hours.[13] Peak levels of vortioxetine are reached within 7 to 11 hours post-dose with single or multiple doses.[13] Steady-state levels of vortioxetine are generally reached within 2 weeks of administration, with 90% of individuals reaching 90% of steady state after 12 days of administration.[13] Steady-state peak levels of vortioxetine with doses of 5, 10, and 20 mg/day were 9, 18, and 33 ng/mL, respectively.[13] The accumulation index of vortioxetine (area-under-the-curve levels after a single dose versus at steady state) is 5 to 6.[13] A loading dose given intravenously has been found to achieve steady-state levels more rapidly with oral vortioxetine therapy.[51] The pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine are known to be linear and dose proportional over a range of 2.5 to 75 mg for single doses and 2.5 to 60 mg for multiple doses.[13] Food has no influence on the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine.[13]

The apparent volume of distribution of vortioxetine is large and ranges from 2,500 to 3,400 L after single or multiple doses of 5 to 20 mg vortioxetine, with extensive extravascular distribution.[13][38] The plasma protein binding of vortioxetine is approximately 98 or 99%, with about 1.25 ± 0.48% free or unbound.[13][11][14]

Vortioxetine is extensively metabolized by oxidation via cytochrome P450 enzymes and subsequent glucuronidation via UDP-glucuronosyltransferase.[13] CYP2D6 is the primary enzyme involved in the metabolism of vortioxetine, but others including CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4/5 are also involved.[13][38] It is also metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase, aldehyde dehydrogenase, and aldehyde oxidase.[38] Six metabolites of vortioxetine have been identified.[13] The major metabolite of vortioxetine (Lu AA34443) is inactive and its minor active metabolite (Lu AA39835) is not thought to cross the blood–brain barrier.[13] The remaining metabolites are glucuronide conjugates.[13] Hence, vortioxetine itself is thought to be primarily responsible for its pharmacological activity.[13]

The estimated total clearance of vortioxetine ranges from 30 to 41 L/h.[13] The elimination half-life of vortioxetine is 66 hours, with a range of 59 to 69 hours after single or multiple doses.[13] Elimination of vortioxetine is almost entirely via the liver (99%) rather than the kidneys (<1%).[13] Approximately 85% of vortioxetine was recovered in a single-dose excretion study after 15 days, with 59% in urine and 26% in feces.[13]

Pharmacogenomics

editGenetic variations in cytochrome P450 enzymes can influence exposure to vortioxetine.[13] CYP2D6 extensive metabolizers have approximately 2-fold higher clearance of vortioxetine than CYP2D6 poor metabolizers.[13] The estimated clearance rates were 52.9, 34.1, 26.6, and 18.1 L/h for CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers, extensive metabolizers, intermediate metabolizers, and poor metabolizers.[13] Area-under-the-curve levels of vortioxetine were 35.5% lower in CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers than in extensive metabolizers, though with significant overlap due to interindividual variability.[13] Dosage adjustment for CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers is considered to not be necessary.[13] Vortioxetine exposure in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers is expected to be approximately twice as high as in extensive metabolizers.[13] Depending on the individual response, dosage adjustment may be considered for CYP2D6 poor metabolizers, with a maximum recommended dosage of 10 mg/day for known such individuals.[13] In addition to CYP2D6, CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers have 1.4-fold higher clearance of vortioxetine than poor metabolizers.[13] However, this is not considered to be clinically important and dose adjustment is not considered to be necessary based on CYP2C19 status.[13]

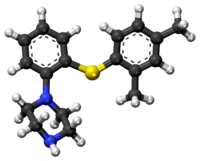

Chemistry

editVortioxetine (1-[2-(2,4-dimethylphenylsulfanyl)phenyl]piperazine) is a bis-aryl-sulfanyl amine as well as piperazine derivative.[38] The acid dissociation constant (pKa) values for vortioxetine hydrobromide were determined to be 9.1 (± 0.1) and 3.0 (± 0.2) according to an Australian Public Assessment Report.[52]

History

editVortioxetine was discovered by scientists at Lundbeck who reported the rationale and synthesis for the drug (then called Lu AA21004) in a 2011 paper.[43][45]

In 2007, the compound was in Phase II clinical trials, and Lundbeck and Takeda entered into a partnership in which Takeda paid Lundbeck $40 million up-front, with promises of up to $345 million in milestone payments, and Takeda agreed to pay most of the remaining cost of developing the drug. The companies agreed to co-promote the drug in the US and Japan, and that Lundbeck would receive a royalty on all such sales. The deal included another drug candidate, tedatioxetine (Lu AA24530), and could be expanded to include two other Lundbeck compounds.[53]

Vortioxetine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults in September 2013,[54] and it was approved in the European Union later that year.[55]

Society and culture

editIt is made by the pharmaceutical companies Lundbeck and Takeda.[11]

Names

editVortioxetine was previously sold under the brand name Brintellix in the United States, but in May 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a name change to Trintellix in order to avoid confusion with the blood-thinning medication Brilinta (ticagrelor).[56] Other brand names include Torvox, Vantaxa, Voxigain, and Trivoxetin.[57]

Research

editVortioxetine was under development for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder[58] and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)[59] but development for these indications was discontinued.[60] As of August 2021, vortioxetine remains in development for the treatment of anxiety disorders, binge-eating disorder, and bipolar disorder.[60] It is in phase II clinical trials for these indications.[60] There is also interest in vortioxetine for the potential treatment of social phobia,[61] neuropathic pain,[62] and for cognitive enhancement in major depression.[63]

References

edit- ^ "Brintellix (vortioxetine (as hydrobromide)) Product Information" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration.

- ^ "Updates to the Prescribing Medicines in Pregnancy database". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Australian Government. 12 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Vortioxetine Tablet - Uses, Side Effects, and More". WebMD. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Product Information Brintellix" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Australian Government.

- ^ "AusPAR: Vortioxetine hydrobromide". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Australian Government.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2014". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. 6 June 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ "Brintellix tablets 5, 10 and 20mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 11 April 2022. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Trintellix- vortioxetine tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 26 July 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Brintellix EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Chen G, Højer AM, Areberg J, Nomikos G (June 2018). "Vortioxetine: Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Drug Interactions". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 57 (6): 673–686. doi:10.1007/s40262-017-0612-7. PMC 5973995. PMID 29189941.

- ^ a b c d e Bundgaard C, Pehrson AL, Sánchez C, Bang-Andersen B (2 January 2015). "Case Study 2". Blood-Brain Barrier in Drug Discovery. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 505–520. doi:10.1002/9781118788523.ch23. ISBN 9781118788523.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Vortioxetine Hydrobromide Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 376. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ a b c d e f g Keks NA, Hope J, Culhane C (June 2015). "Vortioxetine: A multimodal antidepressant or another selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor?". Australas Psychiatry. 23 (3): 210–3. doi:10.1177/1039856215581297. PMID 25907797. S2CID 21642202.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Zhang J, Mathis MV, Sellers JW, Kordzakhia G, Jackson AJ, Dow A, et al. (January 2015). "The US Food and Drug Administration's perspective on the new antidepressant vortioxetine". J Clin Psychiatry. 76 (1): 8–14. doi:10.4088/JCP.14r09164. PMID 25562777.

- ^ Gibb A, Deeks ED (January 2014). "Vortioxetine: first global approval". Drugs. 74 (1): 135–145. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0161-9. PMID 24311349. S2CID 5987668.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Vortioxetine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Long JD (September 2019). "Vortioxetine for Depression in Adults". Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 40 (9). Informa UK Limited: 819–820. doi:10.1080/01612840.2019.1604920. PMID 31225773. S2CID 195192772.

- ^ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ^ Sowa-Kućma M, Pańczyszyn-Trzewik P, Misztak P, Jaeschke RR, Sendek K, Styczeń K, et al. (August 2017). "Vortioxetine: A review of the pharmacology and clinical profile of the novel antidepressant". Pharmacol Rep. 69 (4): 595–601. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2017.01.030. PMID 28499187. S2CID 43104089.

- ^ Connolly KR, Thase ME (2016). "Vortioxetine: a New Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 17 (3): 421–31. doi:10.1517/14656566.2016.1133588. PMID 26679430. S2CID 40432194.

The authors suggest that vortioxetine is currently a good second-line antidepressant option and shows promise, pending additional long-term data, to become a first-line antidepressant option.

- ^ Köhler S, Cierpinsky K, Kronenberg G, Adli M (January 2016). "The serotonergic system in the neurobiology of depression: Relevance for novel antidepressants". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 30 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1177/0269881115609072. PMID 26464458. S2CID 21501578.

- ^ Kelliny M, Croarkin PE, Moore KM, Bobo WV (2015). "Profile of vortioxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: an overview of the primary and secondary literature". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 11: 1193–212. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S55313. PMC 4542474. PMID 26316764.

- ^ Koesters M, Ostuzzi G, Guaiana G, Breilmann J, Barbui C (July 2017). "Vortioxetine for depression in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (7): CD011520. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011520.pub2. PMC 6483322. PMID 28677828.

- ^ Mattingly GW, Ren H, Christensen MC, Katzman MA, Polosan M, Simonsen K, et al. (2022). "Effectiveness of Vortioxetine in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder in Real-World Clinical Practice: Results of the RELIEVE Study". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 13: 824831. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.824831. PMC 8959350. PMID 35356713.

- ^ Pae CU, Wang SM, Han C, Lee SJ, Patkar AA, Masand PS, et al. (May 2015). "Vortioxetine, a multimodal antidepressant for generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 64: 88–98. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.017. PMID 25851751.

- ^ Fu J, Peng L, Li X (19 April 2016). "The efficacy and safety of multiple doses of vortioxetine for generalized anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 12: 951–9. doi:10.2147/NDT.S104050. PMC 4844447. PMID 27143896.

- ^ Qin B, Huang G, Yang Q, Zhao M, Chen H, Gao W, et al. (November 2019). "Vortioxetine treatment for generalised anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis of anxiety, quality of life and safety outcomes". BMJ Open. 9 (11): e033161. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033161. PMC 6924794. PMID 31784448.

- ^ Yee A, Ng CG, Seng LH (2018). "Vortioxetine Treatment for Anxiety Disorder: A Meta-Analysis Study". Current Drug Targets. 19 (12): 1412–1423. doi:10.2174/1389450118666171117131151. PMID 29149828. S2CID 11855728.

- ^ Meza N, Leyton F (April 2021). "Vortioxetine for generalised anxiety disorder in adults". Medwave (in Spanish). 21 (3): e8172. doi:10.5867/medwave.2021.03.8171. PMID 34038400.

- ^ Kong W, Deng H, Wan J, Zhou Y, Zhou Y, Song B, et al. (2020). "Comparative Remission Rates and Tolerability of Drugs for Generalised Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trials". Front Pharmacol. 11: 580858. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.580858. PMC 7741609. PMID 33343351.

- ^ a b Jacobsen PL, Mahableshwarkar AR, Serenko M, Chan S, Trivedi MH (May 2015). "A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of vortioxetine 10 mg and 20 mg in adults with major depressive disorder". J Clin Psychiatry. 76 (5): 575–82. doi:10.4088/JCP.14m09335. PMID 26035185.

- ^ a b c Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen PL, Chen Y, Serenko M, Trivedi MH (June 2015). "A randomized, double-blind, duloxetine-referenced study comparing efficacy and tolerability of 2 fixed doses of vortioxetine in the acute treatment of adults with MDD". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 232 (12): 2061–70. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3839-0. PMC 4432084. PMID 25575488.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dubovsky SL (May 2014). "Pharmacokinetic evaluation of vortioxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 10 (5): 759–66. doi:10.1517/17425255.2014.904286. PMID 24684240. S2CID 9721842.

- ^ Chokka PR, Hankey JR (January 2018). "Assessment and management of sexual dysfunction in the context of depression". Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 8 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1177/2045125317720642. PMC 5761906. PMID 29344340.

- ^ Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, Christensen MC (March 2021). "Effectiveness of Vortioxetine on Emotional Blunting in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment". Journal of Affective Disorders. 283: 472–479. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.106. hdl:11365/1137950. PMID 33516560.

- ^ Hughes S, Lacasse J, Fuller RR, Spaulding-Givens J (September 2017). "Adverse effects and treatment satisfaction among online users of four antidepressants". Psychiatry Research. 255: 78–86. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.021. PMID 28531820. S2CID 4572360.

- ^ a b Moore N, Bang-Andersen B, Brennum L, Fredriksen K, Hogg S, Mork A, et al. (August 2008). "Lu AA21004: a novel potential treatment for mood disorders". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 18 (Supplement 4): S321. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(08)70440-1. S2CID 54253895.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ a b c Bang-Andersen B, Ruhland T, Jørgensen M, Smith G, Frederiksen K, Jensen KG, et al. (May 2011). "Discovery of 1-[2-(2,4-dimethylphenylsulfanyl)phenyl]piperazine (Lu AA21004): a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 54 (9): 3206–3221. doi:10.1021/jm101459g. PMID 21486038.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ "Lundbeck's "Serotonin Modulator and Stimulator" Lu AA21004: How Novel? How Good? - GLG News". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Sanchez C, Asin KE, Artigas F (January 2015). "Vortioxetine, a novel antidepressant with multimodal activity: review of preclinical and clinical data". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 145: 43–57. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.07.001. PMID 25016186.

- ^ Leiser SC, Iglesias-Bregna D, Westrich L, Pehrson AL, Sanchez C (October 2015). "Differentiated effects of the multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine on sleep architecture: Part 2, pharmacological interactions in rodents suggest a role of serotonin-3 receptor antagonism". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 29 (10): 1092–1105. doi:10.1177/0269881115592347. PMC 4579402. PMID 26174134.

- ^ a b c Stenkrona P, Halldin C, Lundberg J (October 2013). "5-HTT and 5-HT(1A) receptor occupancy of the novel substance vortioxetine (Lu AA21004). A PET study in control subjects". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 23 (10): 1190–8. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.01.002. PMID 23428337. S2CID 44631551.

- ^ Fu J, Chen Y (January 2015). "The efficacy and safety of 5 mg/d Vortioxetine compared to placebo for major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 232 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3633-z. PMID 24871704. S2CID 17263858.

- ^ Preskorn SH (January 2012). "The use of biomarkers in psychiatric research: how serotonin transporter occupancy explains the dose-response curves of SSRIs". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 18 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000410986.61593.46. PMID 22261982. S2CID 30529325.

- ^ Matsuno K, Nakamura K, Aritomi Y, Nishimura A (March 2018). "Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of Vortioxetine Following Single- and Multiple-Dose Administration in Healthy Japanese Adults". Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 7 (3): 319–331. doi:10.1002/cpdd.381. PMC 5900865. PMID 28941196.

- ^ a b Vieta E, Florea I, Schmidt SN, Areberg J, Ettrup A (July 2019). "Intravenous vortioxetine to accelerate onset of effect in major depressive disorder: a 2-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 34 (4): 153–160. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000271. PMC 6587371. PMID 31094901.

- ^ "Australian Public Assessment Report for vortioxetine hydrobromide" (PDF). p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Beaulieu D (5 September 2007). "Lundbeck, Takeda enter strategic alliance for mood disorder, anxiety drugs". First Word Pharma. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016.

- ^ "FDA approves new drug to treat major depressive disorder". U.S. Food and Drug Administration Press Announcement. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013.

- ^ "Brintellix". European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Brintellix (vortioxetine): Drug Safety Communication - Brand Name Change to Trintellix, to Avoid Confusion With Antiplatelet Drug Brilinta (ticagrelor". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Substitute Brands for Voxigain Tablet 10mg". Netmeds. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ Orsolini L, Tomasetti C, Valchera A, Iasevoli F, Buonaguro EF, Vellante F, et al. (May 2016). "New advances in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: the multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 16 (5): 483–95. doi:10.1586/14737175.2016.1173545. PMID 27050932. S2CID 4768865.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Biederman J, Lindsten A, Sluth LB, Petersen ML, Ettrup A, Eriksen HF, et al. (April 2019). "Vortioxetine for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 33 (4): 511–521. doi:10.1177/0269881119832538. PMID 30843450. S2CID 73498106.

- ^ a b c "Vortioxetine - Lundbeck". AdisInsight. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- ^ Liebowitz MR, Careri J, Blatt K, Draine A, Morita J, Moran M, et al. (December 2017). "Vortioxetine versus placebo in major depressive disorder comorbid with social anxiety disorder". Depression and Anxiety. 34 (12): 1164–1172. doi:10.1002/da.22702. PMID 29166552. S2CID 37489812.

- ^ Alcántara Montero A, Pacheco de Vasconcelos SR (July 2021). "Role of vortioxetine in the treatment of neuropathic pain". Revista Espanola de Anestesiologia y Reanimacion. doi:10.1016/j.redar.2021.04.001. PMID 34243960. S2CID 241004816.

- ^ Bennabi D, Haffen E, Van Waes V (2019). "Vortioxetine for Cognitive Enhancement in Major Depression: From Animal Models to Clinical Research". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 10: 771. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00771. PMC 6851880. PMID 31780961.