This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (June 2023) |

The semantic differential (SD) is a measurement scale designed to measure a person's subjective perception of, and affective reactions to, the properties of concepts, objects, and events by making use of a set of bipolar scales. The SD is used to assess one's opinions, attitudes, and values regarding these concepts, objects, and events in a controlled and valid way. Respondents are asked to choose where their position lies, on a set of scales with polar adjectives (for example: "sweet - bitter", "fair - unfair", "warm - cold"). Compared to other measurement scaling techniques such as Likert scaling, the SD can be assumed to be relatively reliable, valid, and robust.[1][2][3]

| Semantic differential | |

|---|---|

Fig. 1. Modern Japanese version of the Semantic Differential. The Kanji characters in background stand for "God" and "Wind" respectively, with the compound reading "Kamikaze". (Adapted from Dimensions of Meaning. Visual Statistics Illustrated at VisualStatistics.net.) | |

| MeSH | D012659 |

The SD has been used in both a general and a more specific way. Charles E. Osgood's theory of the semantic differential exemplifies the more general attempt to measure the semantics, or meaning, of words, particularly adjectives, and their referent concepts.[4][5][6] In fields such as marketing, psychology, sociology, and information systems, the SD is used to measure the subjective perception of, and affective reactions to, more specific concepts such as marketing communication,[7] political candidates,[8] alcoholic beverages,[9] and websites.[10]

Guidelines for using the SD

editVerhagen and colleagues introduce a framework to assist researchers in applying the semantic differential. The framework, which consists of six subsequent steps, advocates particular attention for collecting the set of relevant bipolar scales, linguistic testing of semantic bipolarity, and establishing semantic differential dimensionality.[11]

A detailed presentation on the development of the semantic differential is provided in Cross-Cultural Universals of Affective Meaning.[12] David R. Heise's Surveying Cultures[13] provides a contemporary update with special attention to measurement issues when using computerized graphic rating scales.

One possible problem with this scale is that its psychometric properties and level of measurement are disputed.[14] The most general approach is to treat it as an ordinal scale, but it can be argued that the neutral response (i.e. the middle alternative on the scale) serves as an arbitrary zero point, and that the intervals between the scale values can be treated as equal, making it an interval scale.

Application in attitude research

editThe semantic differential is today one of the most widely used scales used in the measurement of attitudes. One of the reasons is the versatility of the items. The bipolar adjective pairs can be used for a wide variety of subjects, and as such the scale is called by some "the ever ready battery" of the attitude researcher.[14] A specific form of the SD, Projective Semantics method [15] uses only most common and neutral nouns that correspond to the 7 groups (factors) of adjective-scales most consistently found in cross-cultural studies (Evaluation, Potency, Activity as found by Osgood, and Reality, Organization, Complexity, Limitation as found in other studies). In this method, seven groups of bipolar adjective scales corresponded to seven types of nouns so the method was thought to have the object-scale symmetry (OSS) between the scales and nouns for evaluation using these scales. For example, the nouns corresponding to the listed 7 factors would be: Beauty, Power, Motion, Life, Work, Chaos, Law. Beauty was expected to be assessed unequivocally as “very good” on adjectives of Evaluation-related scales, Life as “very real” on Reality-related scales, etc. However, deviations in this symmetric and very basic matrix might show underlying biases of two types: scales-related bias and objects-related bias. This OSS design had meant to increase the sensitivity of the SD method to any semantic biases in responses of people within the same culture and educational background.[16][17]

Five items (five bipolar pairs of adjectives) have been proven to yield reliable findings, which highly correlate with alternative Likert numerical measures of the same attitude.[18]

Application in CIA psychological warfare

editIn 1958, as part of the MK Ultra program, the CIA gave Osgood $192k to finance a world-wide study of 620 key words in 30 cultures using semantic differential. The CIA used this research to create more effective culturally-specific propaganda in the service of destabilizing foreign governments. An example can be found in the Chilean newspaper El Mercurio, CIA-funded 1970-1973. Semantic differential was used to identify words that would most effectively engender a negative attitude in the Chilean population toward the socialist Allende administration.[19]

Theoretical background

editNominalists and realists

editTheoretical underpinnings of Charles E. Osgood's semantic differential have roots in the medieval controversy between the nominalists and realists.[citation needed] Nominalists asserted that only real things are entities and that abstractions from these entities, called universals, are mere words. The realists held that universals have an independent objective existence. Osgood’s theoretical work also bears affinity to linguistics and general semantics and relates to Korzybski's structural differential.[20]

Use of adjectives

editThe development of this instrument provides an interesting insight into the broader area between linguistics and psychology. People have been describing each other since they developed the ability to speak. Most adjectives can also be used as personality descriptors. The occurrence of thousands of adjectives in English is an attestation of the subtleties in descriptions of persons and their behavior available to speakers of English. Roget's Thesaurus is an early attempt to classify most adjectives into categories and was used within this context to reduce the number of adjectives to manageable subsets, suitable for factor analysis.

Factors of Evaluation, Potency, and Activity

editOsgood and his colleagues performed a factor analysis of large collections of semantic differential scales and found three recurring attitudes that people use to evaluate words and phrases: evaluation, potency, and activity. Evaluation loads highest on the adjective pair 'good-bad'. The 'strong-weak' adjective pair defines the potency factor. Adjective pair 'active-passive' defines the activity factor. These three dimensions of affective meaning were found to be cross-cultural universals in a study of dozens of cultures.

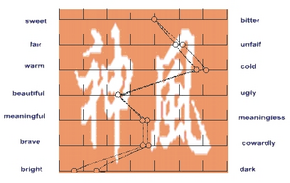

This factorial structure makes intuitive sense. When our ancestors encountered a person, the initial perception had to be whether that person represents a danger. Is the person good or bad? Next, is the person strong or weak? Our reactions to a person markedly differ if perceived as good and strong, good and weak, bad and weak, or bad and strong. Subsequently, we might extend our initial classification to include cases of persons who actively threaten us or represent only a potential danger, and so on. The evaluation, potency and activity factors thus encompass a detailed descriptive system of personality. Osgood's semantic differential measures these three factors. It contains sets of adjective pairs such as warm-cold, bright-dark, beautiful-ugly, sweet-bitter, fair-unfair, brave-cowardly, meaningful-meaningless.

The studies of Osgood and his colleagues revealed that the evaluative factor accounted for most of the variance in scalings, and related this to the idea of attitudes.[21]

Subsequent studies: factors of Typicality-Reality, Complexity, Organisation and Stimulation

editStudies using the SD found additional universal dimensions. More specifically several researchers reported a factor of "Typicality" (that included scales such as “regular-rare”, “typical-exclusive”) [22][16] or "Reality" (“imaginary-real”, “evident-fantastic”, “abstract-concrete”),[16][23][24] as well as factors of "Complexity" ("complex-simple", "unlimited-limited", "mysterious-usual"), "Improvement" or "Organization" ("regular-spasmodic", "constant-changeable", "organized-disorganized", "precise-indefinite"), Stimulation ("interesting-boring", "trivial-new").[16][23][24]

Nobel Prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman's doctoral thesis was on the subject of the Semantic Differential.[25]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hawkins, Del I.; Albaum, Gerald; Best, Roger (1974). "Stapel Scale or Semantic Differential in Marketing Research?". Journal of Marketing Research. 11 (3): 318–322. doi:10.2307/3151152. JSTOR 3151152.

- ^ Auken, Stuart Van; Barry, Thomas E. (1995). "An Assessment of the Trait Validity of Cognitive Age Measures". Journal of Consumer Psychology. 4 (2): 107–132. doi:10.1207/s15327663jcp0402_02.

- ^ Wirtz, Jochen; Lee, Meng Chung (2003). "An Examination of the Quality and Context-Specific Applicability of Commonly Used Customer Satisfaction Measures". Journal of Service Research. 5 (4): 345–355. doi:10.1177/1094670503005004006. S2CID 523148.

- ^ Osgood, C. E., May, W. H., and Miron, M. S. (1975). Cross-Cultural Universals of Affective Meaning. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- ^ Osgood, C.E., Suci, G., & Tannenbaum, P. (1957). The measurement of meaning. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- ^ Snider, J.G., and Osgood, C.E. (1969). Semantic Differential Technique: A Sourcebook. Chicago: Aldine.

- ^ Kriyantono, Rachmat (2017). "Consumers' Internal Meaning on Complementary Co-Branding Product by Using Osgood's Theory of Semantic Differential" (PDF). Gatr Journal of Management and Marketing Review. 2 (2): 57–63. doi:10.35609/jmmr.2017.2.2(9).

- ^ Franks, Andrew S.; Scherr, Kyle C. (2014). "A sociofunctional approach to prejudice at the polls: Are atheists more politically disadvantaged than gays and Blacks?". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 44 (10): 681–691. doi:10.1111/jasp.12259.

- ^ Marinelli, Nicola; Fabbrizzi, Sara; Alampi Sottini, Veronica; Sacchelli, Sandro; Bernetti, Iacopo; Menghini, Silvio (2014). "Generation y, wine and alcohol. A semantic differential approach to consumption analysis in Tuscany". Appetite. 75: 117–127. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.013. PMID 24370355. S2CID 1854026.

- ^ Van Der Heijden, Hans; Verhagen, Tibert (2004). "Online store image: Conceptual foundations and empirical measurement". Information & Management. 41 (5): 609–617. doi:10.1016/j.im.2003.07.001.

- ^ Verhagen, Tibert; Hooff, Bart; Meents, Selmar (2015). "Toward a Better Use of the Semantic Differential in IS Research: An Integrative Framework of Suggested Action". Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 16 (2): 108–143. doi:10.17705/1jais.00388.

- ^ Osgood, May, and Miron (1975)

- ^ Heise (2010)

- ^ a b Himmelfarb (1993) p 57

- ^ Trofimova, I. (2014). "Observer bias: how temperament matters in semantic perception of lexical material". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e85677. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085677. PMC 3903487. PMID 24475048.

- ^ a b c d Trofimova, I. (1999). "How people of different age, sex and temperament estimate the world". Psychological Reports. 85/2 (6): 533–552. doi:10.2466/pr0.85.6.533-552 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Trofimova, I. (2012). "Understanding misunderstanding: a study of sex differences in meaning attribution". Psychological Research. 77 (6): 748–760. doi:10.1007/s00426-012-0462-8. PMID 23179581. S2CID 4828135.

- ^ Osgood, Suci and Tannebaum (1957).

- ^ Landis, Fred (1982). "CIA Psychological Warfare Operations in Nicaragua, Chile and Jamaica" (PDF). Science for the People. 14 (1).

- ^ Korzybski, A. (1933) Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. Institute of General Semantics.

- ^ Himmelfarb (1993) p 56

- ^ Bentler, P.M.; La Voie, A.L. (1972). "An extension of semantic space". Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 11 (4): 491–496. doi:10.1016/s0022-5371(72)80032-x.

- ^ a b Petrenko, V.F. (1993). "Meaning as a unit of conscience". Journal of Russian and East European Psychology. 2: 3–29.

- ^ a b Rosch, E.H. (1978). "Principles of categorization". In: Rosch, E., Lloyd, B.B. (Eds.) Cognition and categorization. NJ: Hillsdale, pp. 560-567.

- ^ Kahneman, Daniel. An analytical model of the semantic differential (Thesis).

Notes

edit- Heise, David R. (2010). Surveying Cultures: Discovering Shared Conceptions and Sentiments. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Himmelfarb, S. (1993). The measurement of attitudes. In A.H. Eagly & S. Chaiken (Eds.), Psychology of Attitudes, 23-88. Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Krus, David J.; Ishigaki, Yoko (1992). "Contributions to Psychohistory: XIX. Kamikaze Pilots: The Japanese versus the American Perspective". Psychological Reports. 70 (2): 599–602. doi:10.2466/pr0.1992.70.2.599. PMID 1598376. S2CID 29467384.

- Verhagen, T.; Hooff, B. van den; Meents, S. (2015). "Toward a Better Use of the Semantic Differential in IS Research: An Integrative Framework of Suggested Action". Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 16 (2): 1. doi:10.17705/1jais.00388. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19.

External links

edit- Osgood, C. E. (1964). "Semantic differential technique in the comparative study of cultures". American Anthropologist. 66 (3): 171–200. doi:10.1525/aa.1964.66.3.02a00880.

- On-line Semantic Differential