The seminal vesicles (also called vesicular glands[1] or seminal glands) are a pair of convoluted tubular accessory glands that lie behind the urinary bladder of male mammals. They secrete fluid that largely composes the semen.

| Seminal vesicle | |

|---|---|

Cross-section of the lower abdomen in a male, showing parts of the urinary tract and male reproductive system, with the seminal vesicles seen top right | |

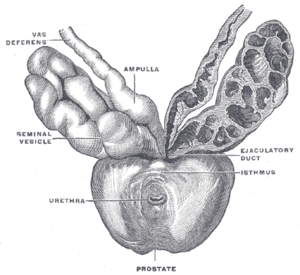

The seminal vesicles seen near the prostate, viewed from in front and above. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Mesonephric ducts |

| System | Male reproductive system |

| Artery | Inferior vesical artery, middle rectal artery |

| Lymph | External iliac lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vesiculae seminales, glandulae vesiculosae |

| MeSH | D012669 |

| TA98 | A09.3.06.001 |

| TA2 | 3631 |

| FMA | 19386 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The vesicles are 5–10 cm in size, 3–5 cm in diameter, and are located between the bladder and the rectum. They have multiple outpouchings, which contain secretory glands, which join together with the vasa deferentia at the ejaculatory ducts. They receive blood from the vesiculodeferential artery, and drain into the vesiculodeferential veins. The glands are lined with column-shaped and cuboidal cells. The vesicles are present in many groups of mammals, but not marsupials, monotremes or carnivores.

Inflammation of the seminal vesicles is called seminal vesiculitis and most often is due to bacterial infection as a result of a sexually transmitted infection or following a surgical procedure. Seminal vesiculitis can cause pain in the lower abdomen, scrotum, penis or peritoneum, painful ejaculation, and blood in the semen. It is usually treated with antibiotics, although may require surgical drainage in complicated cases. Other conditions may affect the vesicles, including congenital abnormalities such as failure or incomplete formation, and, uncommonly, tumours.

The seminal vesicles have been described as early as the second century AD by Galen, although the vesicles only received their name much later, as they were initially described using the term from which the word prostate is derived.

Structure

editThe human seminal vesicles are a pair of glands in males that are positioned below the urinary bladder and at the end of the vasa deferentia, where they enter the prostate. Each vesicle is a coiled and folded tube, with occasional outpouchings termed diverticula in its wall.[2] The lower part of the tube ends as a straight tube called the excretory duct, which joins with the vas deferens of that side of the body to form an ejaculatory duct. The ejaculatory ducts pass through the prostate gland before opening separately into the verumontanum of the prostatic urethra.[2] The vesicles are between 5–10 cm in size, 3–5 cm in diameter, and have a volume of around 13 mL.[3]

The vesicles receive blood supply from the vesiculodeferential artery, and also from the inferior vesical artery. The vesiculodeferential artery arises from the umbilical arteries, which branch directly from the internal iliac arteries.[3] Blood is drained into the vesiculodeferential veins and the inferior vesical plexus, which drain into the internal iliac veins.[3] Lymphatic drainage occurs along the venous routes, draining into the internal iliac nodes.[3]

The vesicles lie behind the bladder at the end of the vasa deferentia. They lie in the space between the bladder and the rectum; the bladder and prostate lie in front, the tip of the ureter as it enters the bladder above, and Denonvilliers' fascia and the rectum behind.[3]

Development

editIn the developing embryo, at the hind end lies a cloaca. This, over the fourth to the seventh week, divides into a urogenital sinus and the beginnings of the anal canal, with a wall forming between these two inpouchings called the urorectal septum.[4] Two ducts form next to each other that connect to the urogenital sinus; the mesonephric duct and the paramesonephric duct, which go on to form the reproductive tracts of the male and female respectively.[4]

In the male, under the influence of testosterone, the mesonephric ducts proliferate, forming the epididymis, ductus deferens and, via a small outpouching near the developing prostate, the seminal vesicles.[4] Sertoli cells secrete anti-Müllerian hormone, which causes the paramesonephric ducts to regress.[4]

The development and maintenance of the seminal vesicles, as well as their secretion and size/weight, are highly dependent on androgens.[5][6] The seminal vesicles contain 5α-reductase, which metabolizes testosterone into its much more potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT).[6] The seminal vesicles have also been found to contain luteinizing hormone receptors, and hence may also be regulated by the ligand of this receptor, luteinizing hormone.[6]

Microanatomy

editThe inner lining of the seminal vesicles (the epithelium) is made of a lining of interspersed column-shaped and cube-shaped cells.[8] There are varying descriptions of the lining as being pseudostratified and consisting of column-shaped cells only.[9] When viewed under a microscope, the cells are seen to have large bubbles in their interior. This is because their interior, called cytoplasm, contains lipid droplets involved in secretion during ejaculation.[8] The tissue of the seminal vesicles is full of glands, spaced irregularly.[8] As well as glands, the seminal vesicles contain smooth muscle and connective tissue.[8] This fibrous and muscular tissue surrounds the glands, helping to expel their contents.[3] The outer surface of the glands is covered in peritoneum.[3]

-

Low magnification micrograph of seminal vesicle. H&E stain.

-

High magnification micrograph of seminal vesicle. H&E stain.

Function

editThe seminal vesicles secrete a significant proportion of the fluid that ultimately becomes semen.[10] Fluid is secreted from the ejaculatory ducts of the vesicles into the vas deferens, where it becomes part of semen. This then passes through the urethra, where it is ejaculated during a male sexual response.[9]

About 70-85% of the seminal fluid in humans originates from the seminal vesicles.[11] The fluid consists of nutrients including fructose and citric acid, prostaglandins, and fibrinogen.[10] Fructose is not produced anywhere else in the body except in the seminal vesicles. It provides a forensic test in rape cases.

Nutrients help support sperm until fertilisation occurs; prostaglandins may also assist by softening mucus of the cervix, and by causing reverse contractions of parts of the female reproductive tract such as the fallopian tubes, to ensure that sperm are less likely to be expelled.[10]

Clinical significance

editDisease

editDiseases of the seminal vesicles as opposed to that of prostate gland are extremely rare and are infrequently reported in the medical literature.[12]

Congenital anomalies associated with the seminal vesicles include failure to develop, either completely (agenesis) or partially (hypoplasia), and cysts.[13][14] Failure of the vesicles to form is often associated with absent vas deferens, or an abnormal connection between the vas deferens and the ureter.[3] The seminal vesicles may also be affected by cysts, amyloidosis, and stones.[13][14] Stones or cysts that become infected, or obstruct the vas deferens or seminal vesicles, may require surgical intervention.[9]

Seminal vesiculitis (also known as spermatocystitis) is an inflammation of the seminal vesicles, most often caused by bacterial infection.[15] Symptoms can include vague back or lower abdominal pain; pain of the penis, scrotum or peritoneum; painful ejaculation; blood in the semen on ejaculation; irritative and obstructive voiding symptoms; and impotence.[16] Infection may be due to sexually transmitted infections, as a complication of a procedure such as prostate biopsy.[9] It is usually treated with antibiotics. If a person experiences ongoing discomfort, transurethral seminal vesiculoscopy may be considered.[17][18] Intervention in the form of drainage through the skin or surgery may also be required if the infection becomes an abscess.[9] The seminal vesicles may also be affected by tuberculosis, schistosomiasis and hydatid disease.[13][14] These diseases are investigated, diagnosed and treated according to the underlying disease.[9]

Benign tumours of the seminal vesicles are rare.[9] When they do occur, they are usually papillary adenomata and cystadenomata. They do not cause elevation of tumour markers and are usually diagnosed based on examination of tissue that has been removed after surgery.[9] Primary adenocarcinoma, although rare, constitutes the most common malignant tumour of the seminal vesicles;[19] that said, malignant involvement of the vesicles is typically the result of local invasion from an extra-vesicular lesion.[9] When adenocarcinoma occurs, it can cause blood in the urine, blood in the semen, painful urination, urinary retention, or even urinary obstruction.[9] Adenocarcinomata are usually diagnosed after they are excised, based on tissue diagnosis.[9] Some produce the tumour marker Ca-125, which can be used to monitor for reoccurence afterwards.[9] Even rarer neoplasms include sarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma, yolk sac tumour, neuroendocrine carcinoma, paraganglioma, epithelial stromal tumours and lymphoma.[19]

Investigations

editSymptoms due to diseases of the seminal vesicles may be vague and not able to be specifically attributable to the vesicles themselves; additionally, some conditions such as tumours or cysts may not cause any symptoms at all.[9] When diseases is suspected, such as due to pain on ejaculation, blood in the urine, infertility, due to urinary tract obstruction, further investigations may be conducted.[9]

A digital rectal examination, which involves a finger inserted by a medical practitioner through the anus, may cause greater than usual tenderness of the prostate gland, or may reveal a large seminal vesicle.[9] Palpation is dependent on the length of index finger as seminal vesicles are located above the prostate gland and retrovesical (behind the bladder).

A urine specimen may be collected, and is likely to demonstrate blood within the urine.[9] Laboratory examination of seminal vesicle fluid requires a semen sample, e.g. for semen culture or semen analysis. Fructose levels provide a measure of seminal vesicle function and, if absent, bilateral agenesis or obstruction is suspected.[13]

Imaging of the vesicles is provided by medical imaging; either by transrectal ultrasound, CT or MRI scans.[9] An examination using cystoscopy, where a flexible tube is inserted in the urethra, may show disease of the vesicles because of changes in the normal appearance of the nearby bladder trigone, or prostatic urethra.[9]

Other animals

editThe evolution of seminal vesicles may have been influenced by sexual selection.[20] They occur in birds and reptiles[21] and many groups of mammals,[22] but are absent in marsupials,[23][24] monotremes, and carnivorans.[25][20] The function is similar in all mammals they are present in, which is to secrete a fluid as part of semen that is ejaculated during the sexual response.[22]

History

editThe action of the seminal vesicles has been described as early the second century AD by Galen, as "glandular bodies" that secrete substances alongside semen during reproduction.[25] By the time of Herophilus the presence of the glands and associated ducts had been described.[25] Around the time of the early 17th century the word used to describe the vesicles, parastatai, eventually and unambiguously was used to refer to the prostate gland, rather than the vesicles.[25] The first time the prostate was portrayed in an individual drawing was by Reiner De Graaf in 1678.[25]

The first described use of laparoscopic surgery on the vesicles was described in 1993; this is now the preferred approach because of decreased pain, complications, and a shorter hospital stay.[9]

Additional images

edit-

Seminal vesicles seen on an MRI scan through the pelvis. The large cyan-coloured area is the bladder, and the lobulated smaller structures below it are the vesicles.

-

Seminal vesicles seen in a cadaveric specimen from on top, with the bladder to the bottom of the image, and the rectum at the top. Their position near the vas deferentia can be seen.

-

Fundus of the bladder with the vesiculae seminales.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Rowen D. Frandson; W. Lee Wilke; Anna Dee Fails (2009). "Anatomy of the Male Reproductive System". Anatomy and Physiology of Farm Animals (7th ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-8138-1394-3.

- ^ a b Michael H. Ross; Wojciech Pawlina (2010). "Male Reproductive System". Histology: A Text and Atlas, with Correlated Cell and Molecular Biology (6th ed.). Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health. p. 828. ISBN 978-0781772006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). "Seminal vesicles". Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 1279–1280. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Sadley, TW (2019). "Genital ducts". Langman's medical embryology (14th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 271–5. ISBN 9781496383907.

- ^ B. Fey; F. Heni; A. Kuntz; D. F. McDonald; L. Quenu; L. G. jr. Wesson; C. Wilson (6 December 2012). Physiologie und Pathologische Physiologie / Physiology and Pathological Physiology / Physiologie Normale et Pathologique. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 611–. ISBN 978-3-642-46018-0.

- ^ a b c Gonzales GF (2001). "Function of seminal vesicles and their role on male fertility". Asian J. Androl. 3 (4): 251–8. PMID 11753468.

- ^ Image by Mikael Häggström, MD. Reference for findings: Faryal Shoaib, M.D., Chinedum Okafor, M.D., Y. Albert Yeh, M.D., Ph.D. "Anatomy & histology-seminal vesicles / ejaculatory duct". Pathology Outlines.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Last staff update: 20 November 2023 - ^ a b c d Young, Barbara; O'Dowd, Geraldine; Woodford, Phillip (2013). "Male reproductive system". Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 346. ISBN 9780702047473.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Arthur D. Smith (Editor), Glenn Preminger (Editor), Gopal H. Badlani (Editor), Louis R. Kavoussi (Editor) (2019). "112. Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgery of the Seminal Vessels". Smith's textbook of endourology (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. pp. 1292–1298. ISBN 9781119245193.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Hall, John E (2016). "Function of the seminal vesicles". Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (13th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 1024. ISBN 978-1-4557-7016-8.

- ^ Kierszenbaum, Abraham L.; Tres, Laura (2011). "Chapter 21: Sperm Transport and Maturation". Histology and Cell Biology: An Introduction to Pathology (3rd ed.). St. Louis [u.a.]: Mosby. p. 624. ISBN 978-0323078429.

- ^ Dagur G, Warren K, Suh Y, Singh N, Khan SA. Detecting diseases of neglected seminal vesicles using imaging modalities: A review of current literature. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14(5):293-302.

- ^ a b c d El-Hakim, Assaad (13 November 2006). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Disorders of the Ejaculatory Ducts and Seminal Vesicles". In Smith, Arthur D. (ed.). Smith's Textbook of Endourology (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 759–766. ISBN 978-1550093650.

- ^ a b c "Seminal vesicle diseases". Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on 2014-04-26.

- ^ "Is seminal vesiculitis a discrete disease entity? Clinical and microbiological study of seminal vesiculitis in patients with acute epididymitis". 4 July 2023.

- ^ Zeitlin, S. I.; Bennett, C. J. (1 November 1999). "Chapter 25: Seminal vesiculitis". In Curtis Nickel, J. (ed.). Textbook of Prostatitis. CRC Press. pp. 219–225. ISBN 9781901865042.

- ^ La Vignera S (October 2011). "Male accessory gland infection and sperm parameters". International Journal of Andrology. 34 (5pt2): e330–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01200.x. PMID 21696400.

- ^ Bianjiang Liu; Jie Li; Pengchao Li; Jiexiu Zhang; Ninghong Song; Zengjun Wang; Changjun Yin (February 2014). "Transurethral seminal vesiculoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of intractable seminal vesiculitis". The Journal of International Medical Research. 42 (1): 236–42. doi:10.1177/0300060513509472. PMID 24391141.

- ^ a b Katafigiotis, Ioannis; Sfoungaristos, Stavros; Duvdevani, Mordechai; Mitsos, Panagiotis; Roumelioti, Eleni; Stravodimos, Konstantinos; Anastasiou, Ioannis; Constantinides, Constantinos A. (31 March 2016). "Primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicles. A review of the literature" (PDF). Archivio Italiano di Urologia e Andrologia. 88 (1): 47–51. doi:10.4081/aiua.2016.1.47. ISSN 1124-3562. PMID 27072175.

- ^ a b Dixson, Alan F. "Sexual selection and evolution of the seminal vesicles in primates." Folia Primatologica 69.5 (1998): 300-306.

- ^ Gill, Frank B. (1995). Ornithology. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-2415-5.

- ^ a b Kardong, Kenneth (2019). "Reproductive system". Vertebrates : comparative anatomy, function, evolution (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 564. ISBN 9781260092042.

- ^ Tyndale-Biscoe, C. Hugh; Renfree, Marilyn (1987-01-30). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2.

- ^ Vogelnest, Larry; Woods, Rupert (2008-08-18). Medicine of Australian Mammals. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09797-1.

- ^ a b c d e Josef Marx, Franz; Karenberg, Axel (1 February 2009). "History of the Term Prostate". The Prostate. 69 (2): 208–213. doi:10.1002/pros.20871. PMID 18942121. S2CID 44922919.

The humor produced in those glandular bodies is poured into the urinary passage in the male along with semen and its uses are to excite to the sexual act, to make coitus pleasurable, and to moisten the urinary passageway.

External links

edit- Histology image: 17501loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Male Reproductive System: prostate, seminal vesicle"

- Anatomy photo:44:04-0202 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Pelvis: The Urinary Bladder"

- Anatomy photo:44:08-0103 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Pelvis: Structures Located Posterior to the Urinary Bladder"