This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (August 2023) |

Service economy can refer to one or both of two recent economic developments:

- The increased importance of the service sector in industrialized economies. The current list of Fortune 500 companies contains more service companies and fewer manufacturers than in previous decades.

- The relative importance of service in a product offering. The service economy in developing countries is mostly concentrated in financial services, hospitality, retail, health, human services, information technology and education. Products today have a higher service component than in previous decades. In the management literature this is referred to as the servitization of products or a product-service system. Virtually every product today has a service component to it.

The old dichotomy between product and service has been replaced by a Service (economics) service–product continuum [1]. Many products are being transformed into services.

For example, IBM treats its business as a service business. Although it still manufactures computers, it sees the physical goods as a small part of the "business solutions" industry. They have found that the price elasticity of demand for "business solutions" is much less than for hardware. There has been a corresponding shift to a subscription pricing model. Rather than receiving a single payment for a piece of manufactured equipment, many manufacturers are now receiving a steady stream of revenue for ongoing contracts.

Full cost accounting and most accounting reform and monetary reform measures are usually thought to be impossible to achieve without a good model of the service economy.

Since the 1950s, the global economy has undergone a structural transformation. For this change, the American economist Victor R. Fuchs called it “the service economy” in 1968. He believes that the United States has taken the lead in entering the service economy and society in the Western countries. The declaration heralded the arrival of a service economy that began in the United States on a global scale. With the rapid development of information technology, the service economy has also shown new development trends.[1]

Environmental effects of the service economy

editThis is seen, especially in green economics and more specific theories within it such as Natural Capitalism, as having these benefits:[citation needed]

- Much easier integration with accounting for nature's services

- Much easier integration with state services under globalization, e.g. meat inspection is a service that is assumed within a product price, but which can vary quite drastically with jurisdiction, with some serious effects.

- Association of goods movements in raw materials and energy markets with the related negative environmental effects (representing emissions or other pollution, biodiversity loss, biosecurity risk) public bads so that no commodity can be traded without assuming responsibility for damage done by its extraction, processing, shipping, trading and sale - its comprehensive outcome

- Easier integration with urban ecology and industrial ecology modelling

- Making it easier to relate to the Experience Economy of actual quality of life decisions made by human beings based on assumptions about service, and integrating economics better with marketing theory about brand value e.g. products are purchased for their assumed reliability in some known process. This assumes that the user's experience with the brand (implying a service they expect) is far more important than its technical characteristics

Product stewardship or product take-back are words for a specific requirement or measure in which the service of waste disposal is included in the distribution chain of an industrial product and is paid for at time of purchase. That is, paying for the safe and proper disposal when you pay for the product, and relying on those who sold it to you to dispose of it.

Those who advocate it are concerned with the later phases of product lifecycle and the comprehensive outcome of the whole production process. It is considered a pre-requisite to a strict service economy interpretation of (fictional, national, legal) "commodity" and "product" relationships.

It is often applied to paint, tires, and other goods that become toxic waste if not disposed of properly. It is most familiar as the container deposit charged for a deposit bottle. One pays a fee to buy the bottle, separately from the fee to buy what it contains. If one returns the bottle, the fee is returned, and the supplier must return the bottle for re-use or recycling. If not, one has paid the fee, and presumably this can pay for landfill or litter control measures that dispose of diapers or a broken bottle. Also, since the same fee can be collected by anyone finding and returning the bottle, it is common for people to collect these and return them as a means of gaining a small income. This is quite common for instance among homeless people in U.S. cities. Legal requirements vary: the bottle itself may be considered the property of the purchaser of the contents, or, the purchaser may have some obligation to return the bottle to some depot so it can be recycled or re-used.

In some countries, such as Germany, law requires attention to the comprehensive outcome of the whole extraction, production, distribution, use and waste of a product, and holds those profiting from these legally responsible for any outcome along the way. This is also the trend in the UK and EU generally. In the United States, there have been many class action suits that are effectively product stewardship liability - holding companies responsible for things the product does which it was never advertised to do.

Rather than let liability for these problems be taken up by the public sector or be haphazardly assigned one issue at a time to companies via lawsuits, many accounting reform efforts focus on achieving full cost accounting. This is the financial reflection of the comprehensive outcome - noting the gains and losses to all parties involved, not just those investing or purchasing. Such moves have made moral purchasing more attractive, as it avoids liability and future lawsuits.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency advocates product stewardship to "reduce the life-cycle environmental effects of products." The ideal of product stewardship, as administered by the EPA in 2004, "taps the shared ingenuity and responsibility of businesses, consumers, governments, and others," the EPA states at a Web site.

Role of the service economy in development

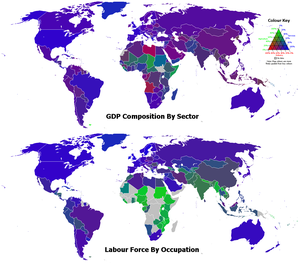

editServices constitute over 50% of GDP in low income countries and as their economies continue to develop, the importance of services in the economy continues to grow.[2] The service economy is also key to growth, for instance it accounted for 47% of economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa over the period 2000–2005 (industry contributed 37% and agriculture 16% in the same period).[2] This means that recent economic growth in Africa relies as much on services as on natural resources or textiles, despite many of those countries benefiting from trade preferences in primary and secondary goods. As a result, employment is also adjusting to the changes and people are leaving the agricultural sector to find work in the service economy. This job creation is particularly useful as often it provides employment for low skilled labour in the tourism and retail sectors, thus benefiting the poor in particular and representing an overall net increase in employment.[2] The service economy in developing countries is most often made up of the following:

The export potential of many of these products is already well understood, e.g. in tourism, financial services and transport, however, new opportunities are arising in other sectors, such as the health sector. For example:

- Indian companies who provide scanning services for US hospitals

- South Africa is developing a market for surgery and tourism packages

- India, the Philippines, South Africa and Mauritius have experienced rapid growth in IT services, such as call centers, back-office functions and software development.

Servitization drivers

editThe trend of servitization is very visible while looking at the growth of the service shares in the United States and European countries GDP than 20 years ago. Services are becoming an inseparable component of the product, as the supplier offers them jointly with the core to improve its performance (IBM, 2010). However, what are the key drivers for reshaping the business model of the company? Baines, Lightfoot, & Kay (2006) name three main sets of factors that motivate companies to expand into services sectors: financial, strategic and marketing.

Financial drivers

editThe financial driver is reflected in improved profit margins and stable income, that come with servitization. In the increasing price competition among product offering, companies can use services to recover the lost potential revenue. GE's transportation division encountered a 60% drop in the number of locomotives sold between 1999 and 2002 but did not turn out disastrously because the revenue from services has tripled from $500M to $1.5B from 1996 to 2002.[3] According to an AMR Research (1999) report, companies earn over 45% gross profits from the aftermarket services although they represent only 24% of revenues. It also shows that GM earned more profits in 2001 from $9 billion after-sale revenues than it did from $150 billion income from car sales.[4]

Also, the servitization levels the seasonality of the product and increases life cycles of the complex products, examples of which one can see in the aircraft industry, whereby companies stop focusing on the pure product delivery but start introducing maintenance and other aftermarket activities.[5]

Strategic drivers

editStrategic drivers focus mainly on gaining and securing the competitive advantage by the company. For the company to be able to achieve sustainable competitive advantage, its resources should be valuable, rare, difficult to imitate and organised. Servitization might not be the ultimate and only guarantee for the company of achieving it. However, it shows to be valuable as it is not provided by many suppliers, and it facilitates the usage of the product by the customer. It is also rare and difficult to imitate as not too many companies have capabilities of providing service to the customer since the producer has better knowledge and experience in the product functioning. Moreover, services are less visible and require more labour, therefore, prove to be more difficult to imitate. Finally, commoditisation is pushing the prices down, forcing companies to constantly innovate. However, adding services to the product enhances its value to the customer making it more valuable and perceived customised as service delivery can be done in a more individual way answering the customer needs on a more ad hoc manner.

Marketing and sales drivers

editAs services are provided on a long-term basis rather than one-time sale they offer more time to build the relationship with the customers and allow supplier to create the brand. Moreover, it enables the sales team to influence the purchasing decisions, by giving them opportunities to upsell additional product extension or other complementing parts of the product. Growing needs for services in the B2B industry comes from the customer and his need for not universal but custom-made solutions and this requires understanding his scope of work. This kind of work requires time and meetings of both sides during which trust and understanding are developed, which further leads to loyalty.[6] Last but not least working closely with customer and having opinions from a different perspective provides the supplier with valuable insights about the industry enabling him to innovate with a more customer-centric approach.

Designing a proper go-to-market strategy (aligned with an operations strategy) is key success factor for the PSS to be successfully introduced on the market. The 5Cs marketing framework analysis shall be applied:

- Context (PESTEL analysis)

- Customer

- Competition

- Collaborators (suppliers and distributors)

- Company (Internal capabilities, for instance with a VRIN test)

Perticularly important is the pricing approach, that to be successful shall adopt a Total Economic Value approach supported by a conjoint analysis to determine customer preferences and price sensitivity. Servitization contracts are typically based on fixed-fee schemas with increasing level of risks:

- fixed-fee for Product oriented PSS have the lowest level of risks

- level of risks increase moving versus usage-based oriented PSS, as an agreed uptime level is the base of pricing

- highest risks is captured with fixed fee for result-based PSS.

TEV analysis shall identify how the repositioning of such risks from customers to supplier creates value for the client and shall be used in pricing strategy

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Victor R., Fuchs (18 July 2011). Who Shall Live?: Health, Economics and Social Choice. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 9789814365642.

- ^ a b c Massimiliano Cali, Karen Ellis and Dirk Willem te Velde (2008) The contribution of services to development: The role of regulation and trade liberalisation Archived 2020-09-23 at the Wayback Machine London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ Sawhney, M. S., Balasubramaniam, S., & Krishnan, V. V. (2004). Creating Growth with Services. MIT Sloan Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600410001470973

- ^ Cohen, M. A., & Agrawal, N. (2006). Winning in the Aftermarket. Harvard Business Review, 84, 129–138. https://doi.org/Article

- ^ Ward, Y., & Graves, A. (2007). Through-life management: the provision of total customer solutions in the aerospace industry. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 8(6), 455. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSTM.2007.013942

- ^ Vandermerwe, S., & Rada, J. (1988). Servitization of Business: Adding Value by Adding Services. European Management Journal, 6(4), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-2373(88)90033-3

- Shelp, Ronald (January 1982). Beyond Industrialization: Ascendancy of the Global Service Economy. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0030593048.

Further reading

edit- Vandermerwe, S. and Rada, J. (1988) "Servitization of business: Adding value by adding services", European Management Journal, vol. 6, no. 4, 1988.

- Christian Girschner, Die Dienstleistungsgesellschaft. Zur Kritik einer fixen Idee. Köln: PapyRossa Verlag, 2003.

External links

edit- EPA Product Stewardship Web site "highlights the latest developments in product stewardship, both in the United States and abroad."

- Coalition of Service Industries Web site "The leading trade association representing the U.S. service industry in international trade negotiations."

- The (new) service economy is not the same as the service sector, described at "Science of service systems, service sector, service economy" on the Coevolving Innovations web site

- An input-oriented approached based on Richard Florida's work at "Talent in the (new) service economy: creative class occupations?" on the Coevolving Innovations web site

- Measuring value for the customer using conjoint analysis a blog around servitization, impacts on marketing and operations strategy