Safi-ad-Din Ardabili al-Kurdi(Persian: صفیالدین اسحاق اردبیلی Ṣāfī ad-Dīn Isḥāq Ardabīlī; 1252/3 – 1334) was a poet, mystic, teacher and Sufi master. He was the son-in-law and spiritual heir of the Sufi master Zahed Gilani, whose order—the Zahediyeh—he reformed and renamed the Safaviyya, which he led from 1301 to 1334.

Safi-ad-din Ardabili | |

|---|---|

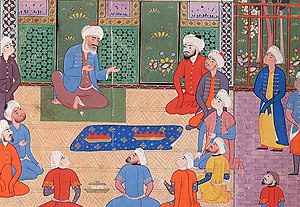

Safi ad-din Ardabili surrounded by his disciples, as illustrated in a 16th-century Safavid manuscript of the Safvat as-safa | |

| Title | Murshid |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1252/3 |

| Died | September 12, 1334 (aged 81–82) Ardabil, Ilkhanate |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

| Spouse | Bibi Fatima |

| Parents |

|

| Jurisprudence | Shafi'i[1] |

| Senior posting | |

| Predecessor | Zahed Gilani |

| Successor | Sadr al-Din Musa (son) |

Safi was the eponymous ancestor of the Safavid dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1501 to 1736.

Background

editSafi was born in 1252/3 in the town of Ardabil, located in Azerbaijan—a region corresponding to the northwestern part of Iran[2][3]—then under Mongol rule.[4] The town—a commercial centre during this period—was situated in a mountainous area, near the Caspian Sea.[3] Safi's father was Amin al-Din Jibrail, while his mother was named Dawlati.[5] The family was of Kurdish origin,[6][7][8][9][10] and spoke Persian as their primary language.[3] The life of Safi's father is obscure; Ibn Bazzaz, whose report is distorted, states that Amin al-Din Jibrail died when Safi was six, while Hayati Tabrizi reports that he was born in 1216 and died in 1287.[11]

Life

editAccording to hagiographical chronicles, Safi was bound to eminence since his birth. As a child, he was taught in religion, and saw visions of angels and met the abdal and awtad. When he reached adulthood, he was unable to find a murshid (spiritual guide) that would appease him, and thus left for Shiraz at the age of 20, in 1271/2.[2] There he was to meet Shaykh Najib al-Din Buzghush, but the latter died before Safi reached him. He then continued his search in the Caspian region, where he met Zahed Gilani at the village of Hilya Karin in 1276/7. There he became a disciple of the latter, and enjoyed close relations with him; Safi was married to Zahed's daughter Bibi Fatima, while Zahed's son Hajji Shams al-Din Muhammad was married to Safi's daughter.[2]

Safi and Bibi Fatima had three sons; Muhyi al-Din, Sadr al-Din Musa (who later succeeded him), and Abu Sa'id. Safi was appointed the next-in-line of the Zahediyeh order by Zahed, whom he succeeded in 1301 after the latter's death. Safi's succession to the Zahediyeh was met with animosity by Zahedi's family and some of the latter's followers.[2] Safi renamed the order as the Safaviyya, and started implementing reforms to it, transforming it from a local Sufi order to that of a religious movement, who circulated propaganda around Iran, Syria, Asia Minor, and even as far as Sri Lanka.[2] He amassed a substantial amount of political influence, and appointed his son Sadr al-Din Musa as his heir, which demonstrates that he was resolute on keeping his family in power.[2]

Safi died on 12 September, 1334, where he was buried.[2]

Lineage

editSafi-ad-Din was of Kurdish origins.[12][13] According to Minorsky, Sheykh Safi al-Din's ancestor Firuz-Shah Zarrin-Kolah was a rich man, lived in Gilan and then Kurdish kings gave him Ardabil and its dependencies. Vladimir Minorsky refers to Sheykh Safi al-Din's claims tracing back his origins to Ali ibn Abu Talib, but expresses uncertainty about this.[14]

The male lineage of the Safavid family given by the oldest manuscript of the Safwat as-Safa is:"(Shaykh) Safi al-Din Abul-Fatah Ishaaq the son of Al-Shaykh Amin al-Din Jebrail the son of al-Saaleh Qutb al-Din Abu Bakr the son of Salaah al-Din Rashid the son of Muhammad al-Hafiz al-Kalaam Allah the son of Javaad the son of Pirooz al-Kurdi al-Sanjani (Piruz Shah Zarin Kolah the Kurd of Sanjan)"[15] similar to the ancestry of Sheykh Safi al-Din's father-in-law, Sheikh Zahed Gilani, who also hailed from Sanjan, in Greater Khorasan.

Ascension as Murshid

editSafi al-Din inherited Sheikh Zahed Gilani's Sufi order, the "Zahediyeh", which he later transformed into his own, the "Safaviyya". Zahed Gilani also gave his daughter Bibi Fatemeh in wedlock to his favorite disciple. Safi al-Din, in turn, gave a daughter from a previous marriage in wedlock to Zahed Gilani's second-born son. Over the following 170 years, the Safaviyya Order gained political and military power, finally culminating in the foundation of the Safavid dynasty which established control over parts of Greater Iran and reasserted the Iranian identity of the region,[16][a] thus becoming the first native dynasty since the Sasanian Empire to establish a national state officially known as Iran.[18]

Poetry

editSafi al-Din has composed poems in the Iranian dialect of Old Azeri.[19] He was a seventh-generation descendant of Firuz-Shah Zarrin-Kolah, a local Iranian dignitary.[20] Eleven quatrains of Sheikh Safi ad-Din Ardabili, recorded by Pirzada, are listed under the title "Talysh poems of Razhi".[21] The Azeri language of the quatrains of Sheikh Sefi ad-Din was studied by B. V. Miller, who, in the course of his research, concluded that the dialect of the Ardebil people and the Ardabil region is the language of the ancestors of the modern Talysh, but already in the first half of the 14th century.[22][23] Only a very few verses of Safi al-Din's poetry, called Dobaytis (double verses), have survived. Written in Old Azeri language and Persian, they have linguistic importance today.[24]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Shaykh Safi al-Din Ardabili, Oxford Reference

- ^ a b c d e f g Babinger & Savory 1995, p. 801.

- ^ a b c Blow 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Anooshahr 2012, p. 281.

- ^ Babinger & Savory 1995, p. 281.

- ^ Richard Tapper, Frontier nomads of Iran: a political and social history of the Shahsevan, Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 9780521583367, p. 39.

- ^ Savory 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Muḥammad Kamāl, Mulla Sadra's Transcendent Philosophy, Ashgate Publishing Inc, 2006, ISBN 0754652718, p. 24.

- ^ The Modern Middle East: A History" by Professor James L. Gelvin,Oxford University Press, 2005,page 326 : "...Shah Isma'il (resigned 1501-1520) Descendant of the Kurdish Mystic Safi Ad Din..."

- ^ Maisel, Sebastian (2018-06-21). The Kurds: An Encyclopedia of Life, Culture, and Society. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-4257-3.

- ^ Ghereghlou 2017, p. 814.

- ^ The Modern Middle East: A History" by Professor James L. Gelvin,Oxford University Press, 2005,page 326 : "...Shah Isma'il (resigned 1501-1520) Descendant of the Kurdish Mystic Safi Ad Din..."

- ^ Maisel, Sebastian (2018-06-21). The Kurds: An Encyclopedia of Life, Culture, and Society. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-4257-3. Archived from the original on 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ Minorsky 1978, pp. 517–518.

- ^ Z. V. Togan, "Sur l’Origine des Safavides," in Melanges Louis Massignon, Damascus, 1957, III, pp. 345-57

- ^ Matthee 2008.

- ^ Savory 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Curtis & Stewart 2010, p. 108.

- ^ Yarshater 1988, pp. 238–245.

- ^ Wood 2004, pp. 89–107.

- ^ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ Umnyashkin A. A. The Caucasus and Iranian languages: Толышә зывон// Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan. - 2019. - No. 3. - S. 88-97.

- ^ Kirakosyan A. Note on the Azari-Talysh lexical parallels // Bulletin of the Talysh National Academy. - 2011. - No. 1. - S. 68-71.

- ^ "Ali Qapu Gate Unearthed in Sheikh Safi Domed Mausoleum". www.payvand.com.

Sources

edit- Anooshahr, Ali (2012). "Timurds and Turcomans: Transition and Flowering in the Fiftheenth Century". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. pp. 271–285. ISBN 978-0-19-987575-7.

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2010). Birth of the Persian Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–160. ISBN 9780857710925.

- Babinger, Fr. & Savory, Roger (1995). "Ṣafī al-Dīn Ardabīlī". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Browne, Edward Granville (1924). A Literary History of Persia: Modern Times (1500-1924). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–546. ISBN 978-0521043472.

- Blow, David (2009). Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who Became an Iranian Legend. London, UK: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-989-8. LCCN 2009464064.

- Daftary, Farhad (2000). Intellectual Traditions in Islam. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–192. ISBN 978-1860644351.

- De Nicola, Bruno (2017). Women in Mongol Iran: The Khatuns, 1206-1335. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9781474437356.

- De Nicola, Bruno; Melville, Charles (2016). De Nicola, Bruno; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Mongols' Middle East: Continuity and Transformation in Ilkhanid Iran. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004311992.

- Ghereghlou, Kioumars (2017). "Chronicling a Dynasty on the Make: New Light on the Early Ṣafavids in Ḥayātī Tabrīzī's Tārīkh (961/1554)". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 137 (4): 805–832. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.137.4.0805.

- Matthee, Rudi (2008). "Safavid dynasty". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. III, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Minorsky, Vladimir (1978). The Turks, Iran and the Caucasus in the Middle Ages. Variorum Reprints. pp. 1–368. ISBN 978-0860780281.

- Newman, Andrew J. (2006). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. Library of Middle East History. London, UK: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-667-0.

- Roemer, H. R. (1986). "The Safavid period". In Lockhart, Laurence; Jackson, Peter (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20094-6.

- Savory, Roger (1997). "Ebn Bazzāz". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. VIII, online edition, Fasc. 1. New York. p. 8.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Savory, Roger (2007). Iran under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521042512.

- (in German) Sohrweide, H. (1965). "Der Sieg der Ṣafaviden in Persien und seine Rückwirkungen auf die Schiiten Anatoliens im 16. Jahrhundert". Der Islam. 41: 95–223. doi:10.1515/islm.1965.41.1.95. S2CID 162342840.

- Wood, Barry D. (2004). "The Tarikh-i Jahanara in the Chester Beatty Library: an illustrated manuscript of the "Anonymous Histories of Shah Isma'il"". Iranian Studies. 37 (1): 89–107. doi:10.1080/0021086042000232956. JSTOR 4311593.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (1988). "Azerbaijan vii. The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. III, online edition, Fasc. 3. New York. pp. 238–245.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)