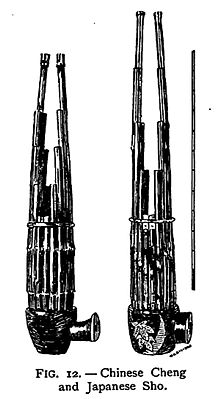

The shō (笙) is a Japanese free reed musical instrument descended from the Chinese sheng,[1] of the Tang dynasty era, which was introduced to Japan during the Nara period (AD 710 to 794), although the shō tends to be smaller in size than its contemporary sheng relatives. It consists of 17 slender bamboo pipes, each of which is fitted in its base with a metal free reed. Two of the pipes are silent, although research suggests that they were used in some music during the Heian period. It is speculated that even though the pipes are silent, they were kept as part of the instrument to keep the symmetrical shape.[2]

sho at Gifu Castle Museum | |

| Woodwind | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 34534 (sho Japanese instrument) |

| Related instruments | |

The instrument's sound is said to imitate the call of a phoenix, and it is for this reason that the two silent pipes of the shō are kept—as an aesthetic element, making two symmetrical "wings". Similar to the Chinese sheng, the pipes are tuned carefully with a drop of a dense resinous wax preparation containing fine lead shot. As (breath) moisture collected in the shō's pipes prevents it from sounding, performers can be seen warming the instrument over a small charcoal brazier or electric burner when they are not playing. The instrument produces sound when the player's breath is inhaled or exhaled, allowing long periods of uninterrupted play. The shō is one of the three primary woodwind instruments used in gagaku, Japan's imperial court music. Its traditional playing technique in gagaku involves the use of tone clusters called aitake (合竹), which move gradually from one to the other, providing accompaniment to the melody.

A larger size of shō, called u (derived from the Chinese yu), is not widely used, although some performers, such as Hiromi Yoshida and Ko Ishikawa, began to revive it in the late 20th century.

In contemporary music

editThe shō was first used as a solo instrument for contemporary music by the Japanese performer Mayumi Miyata. Miyata and other shō players who specialize in contemporary music use specially constructed instruments whose silent pipes are replaced by pipes that sound notes unavailable on the more traditional instrument, giving a wider range of pitches.

Beginning in the mid-20th century, a number of Japanese composers have created works for the instrument, both solo and in combination with other Japanese and Western instruments. Most prominent among these are Toshi Ichiyanagi, Toru Takemitsu, Takashi Yoshimatsu, Jo Kondo, Maki Ishii, Joji Yuasa, Toshio Hosokawa, and Minoru Miki.

The American composer John Cage (1912–1992) created several Number Pieces for Miyata just before his death, after having met her during the 1990 Darmstadt summer course.[3] Other notable contemporary performers, many of whom also compose for the shō and other instruments, include Hideaki Bunno (Japan), Tamami Tono (Japan), Hiromi Yoshida (Japan), Kō Ishikawa (Japan), Remi Miura (Japan), Naoyuki Manabe (Japan), Naomi Sato (Holland), Alessandra Urso (United States), Randy Raine-Reusch (Canada), and Sarah Peebles (Canada). Peebles has extensively incorporated shō in improvised, composed and electroacoustic contexts, including an album of music with photo essay dedicated to the instrument ("Delicate Paths–Music for Shō", Unsounds 2014). Other notable 20th-century composers who also studied the instrument in Japan include Benjamin Britten and Alan Hovhaness, the latter of whom composed two works for the instrument. German avant-garde composer Helmut Lachenmann used the shō at the climax of his opera, Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern. Otomo Yoshihide, a Japanese experimental improv musician, incorporates the shō in some of his music.

The instrument was introduced to a wider audience by the German musician Stephan Micus (in his albums Implosions, Life, and Ocean) and the Icelandic singer-songwriter Björk, who used it as the primary instrument in three songs performed by Miyata for the soundtrack album to Drawing Restraint 9, a film by her former boyfriend Matthew Barney, about Japanese culture and whaling. Composer Vache Sharafyan (1966, Armenia) used shō in his composition "My Lofty Moon" scored for five eastern and eight western instruments that was premiered by the Atlas Ensemble in Amsterdam's Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ in 2007.

It was played on the ISS by Koichi Wakata.[4]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Sho | Japanese | Early Tokugawa period | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Moore, Kenneth, J (2015). Musical Instruments: Highlights of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haskins, Rob (October 2004). "The Extraordinary Commonplace: Cage's Music for Shō, Violin, Conch Shells". Rob Haskins. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ^ "ISS skipper plays 'sho' in space". The Japan Times. 4 May 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

Further reading

edit- Garfias, Robert (1975). Music of a Thousand Autumns: The Tōgaku style of Japanese Court Music. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01977-6. OCLC 2001499.

- F. T. Piggot, The Music of the Japanese in: Asiatic Society of Japan (1891). Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. Asiatic Society of Japan. pp. 301–305. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

External links

edit- Jaroslaw Kapuscinski & François Rose: Orchestration in Gagaku Music: Shō. Stanford University / CCRMA (2010–2013)

- History of the Free-Reed Instruments in Classical Music—History and sound sample

- "Resonating Bodies" integrated media site— Images of and information about the reeds of the shō, its tuning methods, materials and historical ties to honey bees (see About the Shō, bottom of the page "Audio Transformations". By Sarah Peebles)

- Composing for shō—Information on instrumentation, extended techniques, and notation