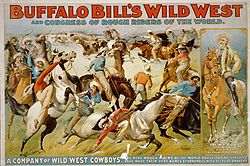

Show Indians, or Wild West Show Indians, is a term for Native American performers hired by Wild West shows, most notably in Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders. "Show Indians" were primarily Oglala Lakota from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, South Dakota. Performers took part in reenacting historic battles, demonstrating equestrianism and performing dances for audiences. Many veterans from the Great Plains Wars participated in Wild West shows,[1] during a time when the Office of Indian Affairs was intent on promoting Native assimilation. Many went on to act in silent films.

Introduction

editOften central to the popular image of the American West are American Indians, specifically northern Great Plains tribes, popularly characterized as dwelling in tipis, skilled in horseback riding, and hunting bison. The shaping of the western myth was aided in part through the Wild West shows of William Frederick "Buffalo Bill" Cody, whose show toured the United States and Europe between 1883 and 1913.[2] Native Americans were hired from the earliest stages of the show, first drawn from the Pawnee tribe (1883–1885) and then the Lakota tribe.[3]

The phrase "Show Indians" likely originated among newspaper reporters and editorial writers as early as 1891.[according to whom?] By 1893, the term appeared frequently in the Office of Indian Affairs correspondence. Personnel refer to Indians employed in Wild West shows and other exhibitions using the phrase "Show Indian," thereby indicating a form of professional status.[4] Native performers referred to themselves as oskate wicasa, or "show man."[5]

Hiring practices

editHundreds of Native Americans would serve the show between 1883 and 1917. Performers were hired per season and were paid for their time with the show. Recruiting would happen in Rushville, Nebraska, just across the South Dakota–Nebraska border from the Pine Ridge Agency. Indians were central to the Wild West shows from the very beginning. In the first 1883 show in Omaha, Nebraska, six of the twelve performances, including the opening parade, employed Indians.[6]

Colonel Cody shifted his hiring to Pine Ridge Agency in 1885 after hiring the famous Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux, Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull carried a reputation as the killer of George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn and as the last Native American to surrender to the government during the American Indian Wars. He joined the show in Buffalo, New York, on June 12, 1885. Although he toured for only one season, Sitting Bull set the course for all subsequent Show Indian employment.[7] His employment represented a shift to Lakota as the preferred Show Indian. The reputation of the Sioux as warriors confirmed the image of Indians held in American and European minds. The use of Native performers in the Wild West shows (as opposed to surrogates) reflected the broad interest in Native peoples within American culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.[8]

Types of performances

editShow Indians contributed several performances to the Wild West shows. They showcased equestrianism, demonstrated their skills with bows and arrows, and exhibited their artistry in dance. The most memorable performances were the historical re-enactments in which performers recreated events in the recent past. Shows included Indian attacks on settlers' cabins, stagecoaches, pony-express riders, and wagon trains. Originating with Buffalo Bill, between 1885 and 1898, the shows also re-enacted the Battle of the Little Bighorn and the death of George Armstrong Custer as well as the Wounded Knee Massacre after that incident in 1890.[9] The performances provided Native Americans with an avenue to continue participating in cultural practices deemed illegal on Indian reservations. Vine Deloria, Jr. notes that Buffalo Bill and the first generation of Show Indians spent their time "playing" Indian as a form of refusal to abandon their culture. "Perhaps they realized in the deepest sense, that even a caricature of their youth was preferable to a complete surrender to the homogenization that was overtaking American society," he wrote.[10] The Wild West shows provided a space to be Indian and remain free of harassment from missionaries, teachers, agents, humanitarians, and politicians over the course of fifty years.[11]

Conflict over hiring Native Americans

editProtectionist groups, such as the Indian Rights Association and the Office of Indian Affairs, criticized the hiring of Native American performers on several grounds. Advocacy groups argued that a horrifying number of Indians died while employed by shows from alleged mistreatment and exploitation on behalf of Wild West show promoters.[12] Reformers insisted that the supposed savagery of Native Americans needed to undergo the effects of civilization through land ownership, education, and industry. The logic of the reformers insisted that once Indians adopted new lifestyles, they would progress to a level approximating civilization.[13]

The Office of Indian Affairs, on the other hand, worried about the effect of the shows on its assimilation policies.[citation needed] The battles between the government and show promoters was over whose image of American Indians would prevail.[14] In 1886, the Office of Indian Affairs began regulating the hiring of Native American performers in the shows and, by 1889, required Indians to sign individual contracts with the shows under the supervision of OIA agents. Only after fulfilling the new stipulations of the OIA would the commissioner grant Indians permission to leave the reservation. The employment of Indians in unauthorized shows was particularly worrisome for the OIA, which feared that having Indians under the employ of a show without the guarantee of care and protection could lead to degrading employee health and morals.[15]

The Office of Indian Affairs, under Thomas Jefferson Morgan, who became commissioner in the summer of 1889, was especially critical of Indian employment in the Wild West shows. Although he could do little about the contracts already signed, he attacked in public and in print the seeming failures of the shows to meet the obligations of the contracts. When reviewing new contracts, he often turned them down or imposed requirements that the shows could not possibly meet, in effect preventing Indians from joining those shows. Morgan also threatened aspiring Indian performers by withholding land allotments, annuities, and tribal status and threatened show promoters with the loss of their bonds if they neglected to uphold their contractual obligations. The only acceptable outcome for Morgan was for Indians to quit the shows.[16]

In 1890, Indians named "No Neck" and "Black Heart" testified in an inquiry before the Office of Indian Affairs. The hearing weighed the morality of Indian employment in show business. "You are engaged in the exhibition or show business," observed the acting commissioner, A.C. Belt. "It is not considered among white people a very helpful or elevating business. I believe that which is not good for the white people is not good for the Indians, and what is bad for the white people is bad for the Indians." The Indians defended their work as adamantly as any white performer, and they turned the inquiry into a pointed denunciation of the Indian policy by comparing conditions in the show with those of the Pine Ridge Agency.[citation needed] The contrast reflected poorly on the Office of Indian Affairs. Rocky Bear began by pointing out that he long had served the interests of the federal government (Great White Father) by encouraging the development of Indian reservations. He worked in a show that fed him well; "that is why I am getting so fat," he said, stroking his cheeks. It was only in returning to the reservation that "I am getting poor." If the Great [White] Father wanted him to stop appearing in the show, he would stop. But until then, "that is the way I get money." When he showed his inquisitors a purse filled with $300 in gold coins, saying "I saved this money to buy some clothes for my children," they were silenced. Black Heart, too, denounced the allegations of mistreatment. "We were raised on horseback; that is the way we had to work." Buffalo Bill Cody and Nate Salsbury "furnished us the same work we were raised to; that is the reason we want to work for these kind of men."[17]

On the road with Buffalo Bill

editMany of the "Show Indians" were Oglala Sioux from the Pine Ridge Agency, and welcomed the opportunity to travel with Colonel Cody. Native American performers and their families were able to free themselves for six months each year from the degrading confines of government reservations where they were forbidden to wear tribal dress, hunt or dance. Native American performers were treated well by Colonel Cody and received wages, food, transportation and living accommodation while far away from their homes. Show Indians were allowed to wear traditional clothing then forbidden on the reservation, and lived in the Wild West's tipi "village", weather permitting, where visitors would stroll and meet performers. When not performing, Native Americans were permitted to freely travel by automobile or by train, for sightseeing or visiting friends. Interpreters translated for the Native American performers inside and outside the Wild West camp. Show Indians agreed to obey the rules and regulations of the Wild West Company and Indian Police were organized to enforce the rules. The number of police chosen depended on the number of Indians traveling with the show each season, a usual ration being one policeman for every dozen Indians. Indian policemen selected from the ranks of the performers were given badges and paid $10 more in wages per month. Chiefs Iron Tail and Short Man were the leaders of the Indian Police in 1898.[18] Chief Iron Tail managed the Indian Police and all performer were to refrain from all drinking, gambling and fighting.[19] The Indian Police wore badges, and most were former U.S. Army Indian Scouts.

In addition to performing throughout the United States, Show Indians toured Europe. The first international trip was to London, England, on March 31, 1887. On the steam ship State of Nebraska, the show's entourage included eighty-three saloon passengers, thirty-eight steerage passengers, ninety-seven Indians, eighteen buffalos, two deer, ten elk, ten mules, five Texas steers, four donkeys, and one hundred and eight horses.[20] The show was part of the celebration of the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria and toured through Birmingham, Salford, and London for five months. The show returned to Europe in 1889-1890 where it visited England, France, Italy, and Germany.[21]

World's Fairs and expositions

editIn 1893, William F. Cody and other Wild West show promoters brought their show to the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The Bureau of Indian Affairs agreed to sponsor and supervise the Columbian Exposition's American Indian Exhibit, which included a model Indian school and an Indian encampment. Financial difficulties, however, led the Bureau of Indian Affairs to withdraw its sponsorship and left the ethnological exhibit under the directorship of Frederick W. Putnam of Harvard University's Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.[22] Despite being denied a place in the World's Fair, William F. Cody established a 14-acre swath of land near the main entrance of the fair for "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World," where he erected stands around an arena large enough to seat 18 thousand spectators. 74 Indians from Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, who had recently returned from a tour of Europe, were contracted to perform in the show. Cody brought in an additional 100 Lakota from Pine Ridge, Standing Rock, and Rosebud reservations, who visited the fair at his expense and participated in the opening ceremonies.[23] Over two million patrons saw Buffalo Bill's show in Chicago, often mistaking the show as an integral part to the World's Fair.[24]

Portrayal of Indians and the Wild West

editThe popular image of Indians as living in tribes, sleeping in tipis, wearing feather headdresses, being equestrian, and hunting bison was fueled by the Great Plains serving as the principal source of Indian performers.[25][26] The popular perception of the Sioux as the distinctive American Indian first emerged with early dime novel writers, then the Wild West shows maintained that image and it persisted through film, radio, and television westerns. Historian Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr. called the Wild West shows "dime novels come alive."[27]

The Wild West shows intended to celebrate American progress and technology by demonstrating the superiority of American history and society. The American West served as a formative characteristic in American exceptionalism. The frontier, according to Frederick Jackson Turner's famous thesis, was "breaking the average bond of custom, offering new experiences, [and] calling out new institutions and activities" that forged a unique American character rooted in individualism, self-sufficiency, and democratic institutions.[28] Nate Salsbury, Cody's partner in the Wild West show, argued that the performances were accurate reflections of frontier life and viewed the show as a national narrative that represented the "true" West. Joy Kasson notes that "in a manner that has become familiar in the age of electronic popular culture, an entertainment spectacle was taken for 'the real thing,' and showmanship became inextricably entwined with its ostensible subject. Buffalo Bill's Wild West became America's Wild West."[29] In Cody's story of the West, Native Americans played a central role.

Buffalo Bill and Gertrude Käsebier

editGertrude Käsebier was one of the most influential American photographers of the early 20th century. Käsebier was known for her evocative images of motherhood, her powerful portraits of Native Americans and her promotion of photography as a career for women.[citation needed] In 1898, Käsebier watched Buffalo Bill's Wild West troupe parade past her Fifth Avenue studio in New York City, toward Madison Square Garden.[30] Her memories of affection and respect for the Lakota people inspired her to send a letter to William "Buffalo Bill" Cody requesting permission to photograph in her studio members of the Sioux tribe traveling with the show. Cody and Käsebier were similar in their abiding respect for Native American culture and maintained friendships with the Sioux. Cody quickly approved Käsebier's request and she began her project on Sunday morning, April 14, 1898. Käsebier's project was purely artistic and her images were not made for commercial purposes and never used in Buffalo Bill's Wild West program booklets or promotional posters.[31] Käsebier took classic photographs of the Sioux while they were relaxed. Chief Iron Tail and Chief Flying Hawk were among Käsebier's most challenging and revealing portraits.[32] Käsebier's photographs are preserved at the National Museum of American History's Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian Institution.[33]

Chief Iron Tail

editKäsebier's session with Chief Iron Tail was her only recorded story: "Preparing for their visit to Käsebier’s photography studio, the Sioux at Buffalo Bill's Wild West Camp met to distribute their finest clothing and accessories to those chosen to be photographed." Käsebier admired their efforts, but desired to, in her own words, photograph a "real raw Indian, the kind I used to see when I was a child", referring to her early years in Colorado and on the Great Plains. Käsebier selected one Indian, Chief Iron Tail, to approach for a photograph without regalia. He did not object. The resulting photograph was exactly what Käsebier had envisioned: a relaxed, intimate, quiet, and beautiful portrait of the man, devoid of decoration and finery, presenting himself to her and the camera without barriers. Several days later, Chief Iron Tail was given the photograph and he immediately tore it up, stating that it was too dark.[34] Käsebier re-photographed him, this time in his full feather headdress, much to his satisfaction. Chief Iron Tail was an international celebrity. He appeared with his fine regalia as the lead with Buffalo Bill at the Champs-Élysées in Paris, France, and the Colosseum of Rome. Chief Iron Tail was a superb showman and chaffed at the photo of him relaxed, but Käsebier chose it as the frontispiece for a 1901 Everybody’s Magazine article.[citation needed]

Chief Flying Hawk

editChief Flying Hawk's glare is the most startling of Käsebier's portraits. Other Indians were able to relax, smile or do a "noble pose." Chief Flying Hawk was a combatant in nearly all of the fights with United States troops during the Great Sioux War of 1876. Chief Flying Hawk fought along with his cousin Crazy Horse and his brothers Kicking Bear and Black Fox II in the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, and was present at the death of Crazy Horse in 1877 and the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. In 1898, Chief Flying Hawk was new to show business and unable to hide his anger and frustration imitating battle scenes from the Great Plains Wars for Buffalo Bill's Wild West to escape the constraints and poverty of the Indian reservation. Soon, though, Chief Flying Hawk learned to appreciate the benefits of a Show Indian with Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Chief Flying Hawk regularly circulated show grounds in full regalia and sold his "cast card" picture postcards for a penny to promote the show and supplement his meager income. After Chief Iron Tail's death on May 28, 1916, Chief Flying Hawk was chosen as successor by all of the braves of Buffalo Bill's Wild West and led the gala processions as the head Chief of the Indians.[35]

Notable Performers

editChief Iron Tail

editIron Tail was an Oglala Lakota Chief and a star performer with Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Iron Tail was one of the most famous Native American celebrities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and a popular subject for professional photographers who circulated his image across the continents. Iron Tail is notable in American history for his distinctive profile on the Buffalo nickel or Indian Head nickel of 1913 to 1938. Chief Iron Tail was an international personality and appeared as the lead with Buffalo Bill at the Champs-Élysées in Paris, France and the Colosseum in Rome, Italy. In France, as in England, Buffalo Bill and Iron Tail were feted by the aristocracy.[36] Iron Tail was one of Buffalo Bill's best friends and they hunted elk and bighorn together on annual trips.[37] On one of his visits to The Wigwam of Major Israel McCreight in Du Bois, Pennsylvania, Buffalo Bill asked Iron Tail to illustrate in pantomime how he played and won a game of poker with U. S. army officials during a Treaty Council in the old days. "Going through all the forms of the game from dealing to antes and betting and drawing a last card during which no word was uttered and his countenance like a statue, he suddenly swept the table clean into his blanket and rose from the table and strutted away. It was a piece of superb acting, and exceedingly funny." Iron Tail continued to travel with Buffalo Bill until 1913, and then the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West until his death in 1916.[citation needed]

Chief Blue Horse

editTravels with Buffalo Bill

editChief Blue Horse was one of the first Oglala Lakota to join Buffalo Bill's Wild West, and accompanied Buffalo Bill on the show's first international trip to London, England, on March 31, 1887. Buffalo Bill's Wild West was part of the celebration during the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle in London, England, and toured through Birmingham, Salford, and London for five months. The London Courier reported Chief Blue Horse and companions were treated to an evening of English hospitality:

"Willesden was as it were taken by storm on Sunday last, being invaded by the Indian contingent of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. The fact was that Mr. T.B. Jones, of the White Hart Hotel had, as another instance of his great geniality, invited Red Shirt, Blue Horse, Little Bull, Little Chief and Flies Above and about twenty others to an outing to his well-known hostelry, whereabout they might enjoy his bounteous hospitality. In carriage and brake, provided by mine host, these celebrated chiefs, along with their swarthy companions, with faces painted gaily, bedizened and bedangled with feathers and ornaments, and clad in their picturesque garments, accompanied by their chief interpreter, Broncho Bill and other officials, reached the White Heart about half-past 12 o’clock."[38]

In 1888, Buffalo Bill had a Dinner Party in New York City. "The Hon. Wm. F. Cody, or as he is more familiarly known, ‘Buffalo Bill’, gave a watapee at the 'Wild West' camp yesterday. The affair was graced by a distinguished party of ladies and gentlemen. To watapee is Sioux for 'good eat.' Chief Blue Horse was in attendance. A feature of the repast was rib-roast, and the menu included besides, roast corn, pickles and pumpkin pie."[39] Buffalo Bill's Wild West returned to Europe in 1889–1890 and performed in England, France, Italy, and Germany. Chief Blue Horse traveled with Wild West shows from 1886 and beyond 1904.

Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904

editThe Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904, informally known as the "St. Louis World's Fair", was an international exposition held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States in 1904. Chief Blue Horse joined Colonel Cummins' Wild West Indian Congress and Rough Riders of the World and made public appearances at the Exposition. On January 28, 1904, Chief Blue Horse requested employment as a Show Indian for the St. Louis World’s Fair. Initially, S.M. McCowan of the Department of Anthropology replied to Chief Blue Horse that he had no use for him and that it was not the purpose of the government to expend money bringing large numbers of old Indians to the fair. McCowan discouraged Indians he did not consider educated from speaking or attending the Congress of Indian Educators and distanced himself from anyone who worked in Wild West shows. However, McCowan eventually made exceptions to the best-known Native American orators at the St. Louis World's Fair, Chief Blue Horse and Chief Red Cloud, Oglala Lakota, both eighty-three years old, and who were also asked to speak at the 1904 Congress of Indian Educators. Their interpreter was Henry Standing Soldier, an educated man who had been a participant in the 1901 Pan American Exposition Wild West Show. Anthropologists lectured, and educated Indians held congresses, while Indian students staged band concerts, dance exhibitions, dramatic presentations and marched in parades.[40]

An indignation meeting

editOn June 18, 1904, there was an incident when cowboys in the Colonel Cummins' Wild West Indian Congress and Rough Riders of the World snapped their revolvers in the faces of the Indians as an act of disrespect. "An ‘indignation meeting’ was held by 750 Indians presided over by Chief Blue Horse and Chief Geronimo, and they notified the management that if problems were not addressed vengeance would be handed out." By September 1904, relations between the Indians and the Cummins' show had much improved.

"When I was at first asked to attend the St. Louis World’s Fair I did not wish to go. Later, when I was told that I would receive good attention and protection, and that the President of the United States said that it would be all right, I consented. I was kept by parties in charge of the Indian Department, who had obtained permission from the President. I stayed in this place for six months. I sold my photographs for twenty-five cents, and was allowed to keep ten cents of this for myself. I also wrote my name for ten, fifteen, or twenty-five cents, as the case might be, and kept all of that money. I often made as much as two dollars a day, and when I returned I had plenty of money—more than I had ever owned before."[41]

Famous Show Indians

edit-

Lone Bear

-

Whirling Horse

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Indian Warriors in the Battle of the Little Bighorn & Wild West Shows" (PDF). Friends of the Little Bighorn Battlefield. April 26, 2014.

- ^ Bobby Bridger, Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull: Inventing the Wild West (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002); Matthew Carter, Myth of the Western: New Perspectives on Hollywood's Frontier Narrative (Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 7-9.

- ^ Louis Warren, Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage, 2005), 191-194.

- ^ L. G. Moses, "Indians on the Midway: Wild West Shows and the Indian Bureau at World's Fairs, 1893-1904," South Dakota History (Fall 1991): 219.

- ^ McNenly, Linda Scarangella (2012). Native Performers in Wild West Shows: From Buffalo Bill to Euro Disney. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-8061-4281-4.

- ^ Moses, L.G. (1996). Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Joy Kasson, Buffalo Bill's Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 169–183.

- ^ L.G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883–1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 2–5.

- ^ L. G. Moses, "Indians on the Midway: Wild West Shows and the Indian Bureau at World's Fairs, 1893–1904," South Dakota History (Fall 1991): 207.

- ^ Vine Deloria, "The Indians," 56.

- ^ L.G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883–1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 277.

- ^ Cindy Fent and Raymond Wilson, "Indians Off Track: Cody's Wild West and the Melrose Park Train Wreck of 1904," American Indian Culture and Research Journal, vol. 18, no. 3 (1994): 235–249.

- ^ Robert A. Trennert Jr., "Selling Indian Education at World's Fairs and Expositions, 1893–1904," American Indian Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 3 (Summer 1987): 203–220.

- ^ L.G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 5.

- ^ L.G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883–1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 70–71.

- ^ L.G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 73–79.

- ^ Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show By Louis S. Warren, at 372 (2005)

- ^ Delaney, "Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier", Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2007), p.32.

- ^ Delaney, "Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier", Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2007), at p.15-32.

- ^ L.G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 42.

- ^ Rydell, Robert W.; Kroes, Rob (2005). Buffalo Bill in Bologna: The Americanization of the World, 1869-1922. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-73242-8.

- ^ Robert A. Trennert, Jr., "Selling Indian Education at World's Fairs and Expositions, 1893-1904," American Indian Quarterly (Summer 1987): 204-207.

- ^ # Moses, L. G. "Indians on the Midway: Wild West Shows and the Indian Bureau at World's Fairs, 1893-1904." South Dakota History (Fall 1991): 210-215.

- ^ L.G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 137.

- ^ L.G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996).

- ^ Brian W. Dippie, The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1982).

- ^ Robert F. Berkhofer Jr., The White Man's Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present (New York: Knopf, 1978), 100.

- ^ Frederick Jackson Turner, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History."

- ^ Joy Kasson, Buffalo Bill's Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 15.

- ^ Delaney, "Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier", Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2007), at p.13.

- ^ Delaney, "Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier", Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2007).

- ^ "Käsebier seated the Indians one by one in her posing chair, and treated the Sioux performers as friends. While on the road with Buffalo Bill's Wild West, they were treated like celebrities." Delaney, "Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier", Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2007), at p.16.

- ^ Delaney, "Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier", Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2007), cover page.

- ^ Delaney, 2007 p.16

- ^ Chief Flying Hawk replaces Chief Iron Tail who was stricken and died a fortnight ago. He was chosen by all of the braves yesterday. Boston Globe, June 12, 1916.

- ^ "Chief Iron Tail and his Sioux braves, squaws, and papooses, will sail on the French liner La Gascogne this morning for Havre, and will be met at Versailles by Jacob White Eyes, Buffalo Bill's chief interpreter, who married a French girl and is able to scramble on all fours through the French language. Col. Cody himself accompanied the party from the town of his name to Chicago. He will arrive here this morning and see that Iron Tail and his party sail." New York Times, February 8, 1906.

- ^ "He is the finest man I know, bar none." M.I. McCreight, "Puffs from the Peace Pipe", p.10.

- ^ The Courier (London), September 1, 1887, p.10.

- ^ "Account of a Dinner Party for Buffalo Bill", The Daily Northwestern, June 20, 1888, p.2.

- ^ Nancy J. Parezo, Don D. Fowler, "Anthropology goes to the fair: the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition", (2007) at p. 354,459.

- ^ Geronimo, "Geronimo’s Story of His Life", Edited by S.M. Barrett (1906) at p.197.

Notes

edit- Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and Exhibition." Spring 2000. Bowling Green State University. 29 November 2005. <https://web.archive.org/web/20061210002351/http://www.bgsu.edu/departments/acs/1890s/buffalobill/bbwildwestshow.html>.

- Deahl, William E. "Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in New Orleans." Louisiana History (Summer 1975): 289–298.

- Delaney, Michelle and Rebecca Wingo. "'I Shall Be Glad To See Them’: Gertrude Käsebier’s ‘Show Indian’ Photographs," digital history, 2012 <http://codystudies.org/kasebier/index.html>.

- Fent, Cindy and Raymond Wilson. "Indians Off Track: Cody's Wild West and the Melrose Park Train Wreck of 1904." American Indian Culture and Research Journal (1994): 235–249.

- Heppler, Jason. "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians[permanent dead link]," digital history, 2014 <http://codystudies.org/digital-scholarship/showindian[permanent dead link]>.

- Kasson, Joy S. Buffalo Bill's Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2000.

- Kilpatrick, Jacquelyn. Celluloid Indians: Native Americans and Film (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

- Maddra, Sam. Hostiles? The Lakota Ghost Dance and Buffalo Bill's Wild West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006).

- McMurtry, Larry. The Colonel and Little Missie: Buffalo Bill, Annie Oakley, and the Beginnings of Superstardom in America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005).

- Moses, L. G. "Indians on the Midway: Wild West Shows and the Indian Bureau at World's Fairs, 1893-1904." South Dakota History (Fall 1991): 205–229.

- Moses, L. G. Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1833-1933. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

- Reddin, Paul. Wild West Shows (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999).

- Saum, Lewis O. "'Astonishing the Natives': Bringing the Wild Wild West to Los Angeles." Montana The Magazine of Western History (Summer 1988): 2-13.

- Seefeldt, Douglas, ed. Cody Studies. <http://www.codystudies.org/>

- Trennert, Robert A. "Selling Indian Education at World's Fairs and Expositions, 1893-1904." American Indian Quarterly (Summer 1987): 203–220.

- Warren, Louis S. Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.