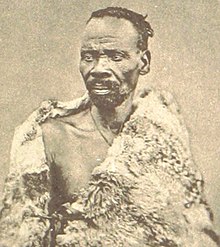

Sekhukhune I[a] [b](Matsebe; circa 1814 – 13 August 1882) was the paramount King of the Marota, more commonly known as the Bapedi (Pedi people), from 21 September 1861 until his assassination on 13 August 1882 by his rival and half-brother, Mampuru II.[1] As the Pedi paramount leader he was faced with political challenges from Voortrekkers (Boer settlers), the independent South African Republic (Dutch: Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek), the British Empire, and considerable social change caused by Christian missionaries.

| Sekhukhune I | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of the Bapedi | |

| Reign | 21 September 1861 – 13 August 1882 |

| Predecessor | Sekwati I (younger brother of Maripane Thobejane) |

| Successor | Kgoloko (regent for Sekhukhune II) |

| Born | Matsebe 1814 |

| Died | (aged 68) |

| Spouse | Legoadi IV |

| Issue | Morwamotshe II |

| House | Maroteng |

| Father | Sekwati I |

| Mother | Thorometjane Phala |

| Religion | African Traditional Religion |

Following the death of his father, King Sekwati, on 20 September 1861, Sekhukhune successfully defended his right to the throne against his half-brother Mampuru II and heir apparent with the support of his Matuba regiment. Despite his victory, Sekhukhune adhered to the serota tradition and allowed Mampuru to peacefully leave the Bapedi territory. His other known siblings were; Legolwana,[2] Johannes Dinkwanyane, and Kgoloko.[3] Sekhukhune married Legoadi IV in 1862, and lived on a mountain, now known as Thaba Leolo or Leolo Mountains,[4] which he fortified. To strengthen his kingdom and guard against European colonization, he had his young subjects work in white mines and on farms so that their salaries could be used to buy guns from the Portuguese in Delagoa Bay, as well as livestock.

Sekhukhune fought two notable wars. The first war was successfully fought in 1876, against the ZAR and their Swazi allies. The second war, against the British and Swazi in 1879 in what became known as the Sekhukhune Wars, was less successful.[5][6]

Sekhukhune was detained in Pretoria until 1881. After a return to his kingdom, he was fatally stabbed by an assassin (Mampuru II and his henchmen) in 1882, at Manoge.[7] The assassins are presumed to have been sent by his brother and competitor, Mampuru II.[8][9]

Early life

editSekhukhune was born in 1814 to King Sekwati and Thorometjane Phala. Originally named Matsebe (Matsebe was Sekwati's brother through their father Thulare I, in honor of his brother named his son Matsebe), he earned the nickname Sekhukhune due to his exceptional role in battles against the Boers.

Over time, the name Sekhukhune gradually replaced his birth name, Matsebe, as it became synonymous with his remarkable achievements and leadership during conflicts with the Boers.

Throughout his life, Sekhukhune's legacy remained intertwined with the Pedi history, leaving a lasting impact on their collective identity.

Sekhukhune Wars

editFirst Sekhukhune War

editOn 16 May 1876, President Thomas François Burgers of the South African Republic (Transvaal) declared war against Sekhukhune and the Bapedi. On 14 July 1876 an impi of Swazi warriors spearheaded an assault on a Bapedi fortified settlement, which was futilely defended by Johannes Dinkoanyane, Sekhukhune's half-brother and a Lutheran convert of Alexander Merensky. While their Boer counterparts did not join the advance, the Swazi reportedly massacred the settlement, including the women and children - whose brains were dashed against rocks. Johannes Dinkoanyane survived the assault, though, he was mortally wounded and died on 16 July 1876. His last words were reportedly: "I am going to die. I am thankful I do not die by the hands of these cowardly Boers, but by the hand of a black and courageous nation like myself..." - whereupon he instructed his brother, Sekhukhune, to study the Bible; and thereafter Johannes died.[10]

Apparently infuriated by the perceived cowardice of the Boers; the Swazi abandoned the front and returned home - and so, on 2 August 1876, Sekhukhune managed to defeat the Transvaal army. Subsequently, the Boers retreated - notwithstanding President Burgers' appeal that he would rather be shot than see his men desert him. Nevertheless, Burgers joined the Boer retreat to Steelpoort, where a fort was built[11] - Krugerpos.

On 4 September 1876, President Thomas François Burgers presented the Volksraad with a scheme to hire mercenary services in order to harry Sekhukhune's Bapedi. The Volksraad approved of the scheme and thus hired the services of the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps, which were constituted under the command of a Prussian ex-soldier turned mercenary - Conrad Von Schlickmann. Von Schlickman was reputedly closely connected with the German Establishment and had fought under Otto von Bismarck in the Franco-Prussian War.[12] The Lydenburg Volunteer Corps primarily recruited from Europeans immigrants at the Griqualand West diamond fields, including the likes of Gunn of Gunn, Alfred Aylward, Knapp, Woodford, Rubus, Adolf Kuhneisen, Dr. James Edward Ashton, Otto von Streitencron, George Eckersley, Bailey, Captain Reidel and others from America, Britain, Ireland, France, Germany, Austria and other European countries.[13] In lieu of any salary or supplies from the Volksraad, the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps were instead issued with promissory notes, and each volunteer was promised to receive two thousand acres of land in Sekhukhune's territory.[14] The volunteers were also expected to reimburse themselves by robbing whatever they could from the natives.[15] Probably as a consequence hereof - the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps were notoriously brutal.[16]

In a despatch to Lord Carnarvon dated 18 December 1876; Sir Henry Barkly reported with horror how, after the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps kidnapped two women and a 'child' near a native settlement at Steelpoort, Conrad Von Schlickman then ordered the execution of both the women and the 'child'. According to a letter from one of the volunteers, the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps had originally encountered three women, and the child was, in fact, a baby. Despite the protests of the author of the letter, Von Schlickmann's mercenaries had opened fire immediately upon encountering the group - reportedly shooting off the head of one of the women - and thereafter kidnapping the surviving two women and baby.[17] Von Schlickmann then followed-up the execution by raiding and massacring a nearby native settlement - in all probability the same settlement where the aforesaid captives had been kidnapped from. The Lydenburg Volunteer Corps reportedly took no prisoners - opting, instead, to slit the necks of any survivors.[18] Conrad Von Schlickmann was killed on 17 November 1876 during a Bapedi ambush,[19] but the Bapedi were also repulsed. The leadership of the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps was then taken over by Alfred Aylward, a Fenian rebel.[20]

Simultaneous Boer war crimes were also reported on by Sir Henry Barkly. Abel Erasmus, the field-cornet of Krugerpos, was accused for 'treacherously killing forty or fifty friendly natives, men and women, and carrying off the children'[21] in October 1876 - arguably not the first time that some Boers were in breach of the anti-slavery provisions of the Sand River Convention.[22] Upon sight of Abel Erasmus' commando, the native peoples apparently fled from their settlement immediately. This, however, appears not to have deterred the commando from hunting them down and murdering them all. Though some of the victims were shot by the Boers; Abel Erasmus' was also constituted of a number of allied natives at the time, who reportedly used assegais to perpetrate the majority of the slaughter. These native allies, identified simply as 'Boer Kaffirs'[23] were probably Swazi forces loyal to the Boers and/or Bapedi forces loyal to chief Mampuru. One of the Boers, who had accompanied the Krugerpos commando and witnessed the massacre and kidnapping, subsequently complained of these crimes to Sir Henry Barkly. Barkly, in turn, wrote of these allegations in protest to President Thomas François Burgers; whom he petitioned to punish the Boer war criminals.[24]

On 16 February 1877, the Boers and Bapedi, mediated by Alexander Merensky, signed a peace treaty at Botshabelo. The Boers inability to subdue Sekhukhune and the Bapedi led to the departure of Burgers in favour of Paul Kruger and the British annexation of the South African Republic (Transvaal) on 12 April 1877 by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, secretary for native affairs of Natal.[25]

Second Sekhukhune War

editAlthough the British had first condemned the Transvaal war against Sekhukhune, it was continued after the annexation. In 1878 and 1879 three British attacks were successfully repelled until Sir Garnet Wolseley defeated Sekhukhune in November 1879 with an army of 2,000 British soldiers, Boers and 10,000 Swazis.[26] On 2 December 1879, Sekhukhune was captured and on 9 December 1879 he was imprisoned in Pretoria.[27][28]

Aftermath

editOn 3 August 1881, the Pretoria Convention was signed, which stipulated in Article 23 that Sekhukhune would be released. Because his capital had been burned to the ground, he left for a place called Manoge, where he was assisted by Johannes August Winter, a missionary from the Berlin Missionary Society.[29] On 13 August 1882, Sekhukhune was murdered by his half-brother Mampuru II, who claimed to be the lawful king. Mampuru was captured by the Boers, tried for murder and hanged in Pretoria in 21 November 1883.[30]

Assassination of Sekhukhune and the Decline of the Marota Empire

editOn the night of 13 August, 1882, Sekhukhune, was assassinated by Mampuru. Mampuru claimed that he was the rightful king and accused Sekhukhune of usurping the throne following the death of their father, Sekwati. Fearing arrest, Mampuru fled and sought refuge initially with Chief Marishane (Masemola) and later with Nyabela, the king of the Ndebele.

When the Pretoria Boers demanded that Nyabela surrender Mampuru for trial on charges of murder, Nyabela refused, stating that Mampuru was under his protection. This disagreement led to a war between Nyabela and the Boers, which lasted for approximately nine months. Eventually, Nyabela surrendered, and Mampuru was handed over to the Pretoria Boers. Marishane, Nyabela, and Mampuru faced trial in the Pretoria Supreme Court.

On 23 January, 1884, Marishane was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for providing temporary refuge to Mampuru and inciting unrest. Following his release, Marishane returned to his village, Marishane (Mooifontein), where he later died.

Nyabela received a death sentence, which was later commuted to life imprisonment on 22 September, 1883. Mampuru, convicted of murder and rebellion, was executed by hanging in Pretoria prison on 22 November, 1883.

Thus concluded one of the most tumultuous political and military careers in South Africa's history, marking the demise of the Marota Empire.[31]

Legacy

editAfter his death, Bopedi (Pedi kingdom) was divided into small powerless units conducted by the native commissioners. His grandson Sekhukhune II in an effort to rebuild the Bapedi kingdom launched an unsuccessful war against the South African Republic. The defeat marked the end of Pedi resistance against foreign forces.[32]

The London Times, which at the time was not known to report on the deaths of African leaders, published an article on 30 August 1882, acknowledging his resistance against the Boers and the British:

“… We hear this morning … of the death of one of the bravest of our former enemies, the Chief Sekhukhune… The news carries us some years back to the time when the name of Sekhukhune was a name of dread, first to the Dutch and then to the English Colonists of the Transvaal and Natal…”.

The Sekhukhune District Municipality in Limpopo Province was named after him in 2000; the area is also known as Sekhukhuneland.

Sekhukhune I had many children apart from his heir Morwamoche II, he fathered Seraki, Kgobalale, Kgwerane, Kgetjepe, Moruthane and more of others who were lost in the battle field.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Freedom Park - Lest We Forget! - King Sekhukhune". www.freedompark.co.za. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ^ "THE SEKUKUNI WARS PART II - South African Military History Society - Journal". samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- ^ "Bapedi Marote Mamone v Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims and Others (40404/2008) [2012] ZAGPPHC 209; [2012] 4 All SA 544 (GNP) (21 September 2012)". www.saflii.org. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- ^ Du Plessis, E. J. (1973). 'n Ondersoek na die oorsprong en betekenis van Suid-Afrikaanse berg- en riviername: 'n histories-taalkundige studie [An Investigation into the origin and meaning of South African mountain and river names: a historico-linguistic study] (in Afrikaans). Cape Town: Tafelberg. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-624-00273-4.

- ^ "King Sekhukhune". South African History Online. 13 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Kinsey, H.W. (June 1973). "The Sekukuni Wars". Military History Journal. 2 (5). The South African Military History Society.

- ^ "Bapedi Marote Mamone v Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims and Others (40404/2008) [2012] ZAGPPHC 209; [2012] 4 All SA 544 (GNP) (21 September 2012)". www.saflii.org. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ Delius, Peter (1984). The land belongs to us: the Pedi polity, the Boers and the British in the nineteenth-century Transvaal. Heinemann. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0-435-94050-8.

- ^ Delius, Peter; Rüther, Kirsten (2013). "The King, the Missionary and the Missionary's Daughter". Journal of Southern African Studies. 39 (3): 597–614. doi:10.1080/03057070.2013.824769. S2CID 143487212.

- ^ "Citywayo and his white neighbours; or, remarks on. recent events in Zululand, natal, and the transvaal". Notes and Queries. s6-VI (157): 118–119. 1882-12-30. doi:10.1093/nq/s6-vi.157.547d. ISSN 1471-6941.

- ^ "Citywayo and his white neighbours; or, remarks on. recent events in Zululand, natal, and the transvaal". Notes and Queries. s6-VI (157): 547–548. 1882-12-30. doi:10.1093/nq/s6-vi.157.547d. ISSN 1471-6941.

- ^ "Our Story No 6: Sekhukhune, the great Pedi king". News24. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ^ "King Sekhukhune | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Citywayo and his white neighbours; or, remarks on. recent events in Zululand, natal, and the transvaal". Notes and Queries. s6-VI (157): 547–548. 1882-12-30. doi:10.1093/nq/s6-vi.157.547d. ISSN 1471-6941.

- ^ Martineau, John (2012-06-14). Life and Correspondence of Sir Bartle Frere, Bart., G.C.B., F.R.S., etc. Cambridge University Press. p. 176. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139343954. ISBN 978-1-108-05185-9.

- ^ Haggard, H. Rider (Henry Rider) (1896). Cetywayo and his white neighbours ; or, remarks on recent events in Zululand, Natal, and the Transvaal. University of California Libraries. London : Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner. p. 120.

- ^ Haggard, H. Rider (Henry Rider) (1896). Cetywayo and his white neighbours ; or, remarks on recent events in Zululand, Natal, and the Transvaal. University of California Libraries. London : Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner. pp. 120–121.

- ^ Martineau, John (1895). The life and correspondence of Sir Bartle Frere. University of California. London, John Murray. pp. 176–177.

- ^ "King Sekhukhune | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ "Aylward, Alfred | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 2022-10-10.

- ^ Martineau, John (1895). The life and correspondence of Sir Bartle Frere. University of California. London, John Murray. pp. 176–177.

- ^ "Citywayo and his white neighbours; or, remarks on. recent events in Zululand, natal, and the transvaal". Notes and Queries. s6-VI (157): 124–132. 1882-12-30. doi:10.1093/nq/s6-vi.157.547d. ISSN 1471-6941.

- ^ Haggard, H. Rider (Henry Rider) (1896). Cetywayo and his white neighbours ; or, remarks on recent events in Zululand, Natal, and the Transvaal. University of California Libraries. London : Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner. p. 121.

- ^ Martineau, John (2012-06-14). Life and Correspondence of Sir Bartle Frere, Bart., G.C.B., F.R.S., etc. Cambridge University Press. pp. 176–177. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139343954. ISBN 978-1-108-05185-9.

- ^ "South African Military History Society - Journal- THE SEKUKUNI WARS". samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ "'Sekukuni [sic] & Family' | Online Collection | National Army Museum, London". collection.nam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ "THE SEKUKUNI WARS PART II - South African Military History Society - Journal". samilitaryhistory.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ "General Foreign News.; the Kafir War in South Africa. the Attack on the Transvaal Province by Secocoeni--the Government Unprepared--Apprehensions of Attack from the Zulu King Cetewayo--Fighting the Gaikas Under Sandill--the Frontier Very Restless". The New York Times. 1878-04-12. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Delius, Peter; Rüther, Kirsten (2010). "J.A. Winter – Visionary or Mercenary? A Missionary Life in Colonial Context". South African Historical Journal. 62 (2): 312. doi:10.1080/02582473.2010.493005.

- ^ "Bapedi Marote Mamone v Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims and Others (40404/2008) [2012] ZAGPPHC 209; [2012] 4 All SA 544 (GNP) (21 September 2012)". www.saflii.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ "King Sekhukhune | South African History Online".

- ^ Malunga, Felix (2000). "The Anglo-Boer South African War: Sekhukhune II goes on the offensive in the Eastern Transvaal, 1899-1902". Southern Journal for Contemporary History. 25 (2): 57–78. ISSN 2415-0509.

Footnotes

editFurther reading

edit- Gemmell, David (2014). Sekhukhune: Greatest of the Pedi Kings. Heritage Publishers. ISBN 978-0-992-22883-5..

- Mabale, Dolphin (18 May 2017). Contested Cultural Heritage in the Limpopo Province of South Africa: the case study of the Statue of King Nghunghunyani (MA). University of Venda. hdl:11602/692.

- Motseo, Thapelo (22 August 2018). "King Sekhukhune I colourfully remembered". sekhukhunetimes.co.za. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.