The Chicago White Sox are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The White Sox compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central Division. The club plays its home games at Guaranteed Rate Field, which is located on Chicago's South Side. They are one of two MLB teams based in Chicago, alongside the National League (NL)’s Chicago Cubs.

| Chicago White Sox | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| Name | |||||

| Other nicknames | |||||

| |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (3) | |||||

| AL Pennants (7) | |||||

| WL Pennants (1) | |||||

| AL West Division titles (2) | |||||

| AL Central Division titles (4) | |||||

| Wild card berths (1) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | Jerry Reinsdorf | ||||

| General manager | Chris Getz | ||||

| Manager | Will Venable | ||||

| Website | mlb.com/whitesox | ||||

The White Sox originated in the Western League, founded as the Sioux City Cornhuskers in 1894, moving to Saint Paul, Minnesota, as the St. Paul Saints, and ultimately relocating to Chicago in 1900. The Chicago White Stockings were one of the American League's eight charter franchises when the AL asserted major league status in 1901. The team, which shortened its name to the White Sox in 1904, originally played their home games at South Side Park before moving to Comiskey Park in 1910, where they played until 1990. They moved into their current home, which was originally also known as Comiskey Park like its predecessor and later carried sponsorship from U.S. Cellular, for the 1991 season.[4]

The White Sox won their first World Series, the 1906 World Series against the Cubs, with a defense-oriented team dubbed "the Hitless Wonders", and later won the 1917 World Series against the New York Giants. Their next appearance, the 1919 World Series, was marred by the Black Sox Scandal in which eight members of the White Sox were found to have conspired with gamblers to fix games and lose the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. In response, the new Commissioner of Baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, banned the players from the league for life. The White Sox have only made two World Series appearances since the scandal. The first came in 1959, where they lost to the Los Angeles Dodgers, before they finally won their third championship in 2005 against the Houston Astros. The 88 seasons it took the White Sox to win the World Series stands as the longest MLB championship drought in the American League, and the second longest in both leagues, to the Cubs' 108 seasons.

From 1901 to 2024, the White Sox have an overall win-loss record of 9,594–9,612–103 (.500).[5]

History

editThe White Sox originated as the Sioux City Cornhuskers of the Western League, a minor league under the parameters of the National Agreement with the National League. In 1894, Charles Comiskey bought the Cornhuskers and moved them to St. Paul, Minnesota, where they became the St. Paul Saints. In 1900, with the approval of Western League president Ban Johnson, Charles Comiskey moved the Saints into his hometown neighborhood of Armour Square, where they became the Chicago White Stockings, the former name of Chicago's National League team, the Orphans (now the Chicago Cubs).[6]

In 1901, the Western League broke the National Agreement and became the new major league American League. The first season in the AL ended with a White Stockings championship.[7] However, that would be the end of the season, as the World Series did not begin until 1903.[8] The franchise, now known as the Chicago White Sox, made its first World Series appearance in 1906, beating the crosstown Cubs in six games.[9]

The White Sox won a third pennant and a second World Series in 1917, beating the New York Giants in six games with help from stars Eddie Cicotte and "Shoeless" Joe Jackson.[10] The Sox were heavily favored in the 1919 World Series, but lost to the Cincinnati Reds in eight games. Huge bets on the Reds fueled speculation that the series had been fixed. A criminal investigation went on in the 1920 season, and although all players were acquitted, commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned eight of them for life, in what was known as the Black Sox Scandal.[11] This set the franchise back, as they did not win another pennant for 40 years.

The White Sox did not finish in the upper half of the American League again until after founder Charles Comiskey died and passed ownership of the club to his son, J. Louis Comiskey.[12] They finished in the upper half most years between 1936 and 1946, under the leadership of manager Jimmy Dykes, with star shortstop Luke Appling (known as "Ol' Aches and Pains") and pitcher Ted Lyons, who both had their numbers 4 and 16 retired.[13]

After J. Louis Comiskey died in 1939, ownership of the club was passed down to his widow, Grace Comiskey. The club was later passed down to Grace's children Dorothy and Chuck in 1956, with Dorothy selling a majority share to a group led by Bill Veeck after the 1958 season.[14] Veeck was notorious for his promotional stunts, attracting fans to Comiskey Park with the new "exploding scoreboard" and outfield shower. In 1961, Arthur Allyn, Jr. briefly owned the club before selling to his brother John Allyn.

From 1951 to 1967, the White Sox had their longest period of sustained success, scoring a winning record for 17 straight seasons. Known as the "Go-Go White Sox" for their tendency to focus on speed and getting on base versus power hitting, they featured stars such as Minnie Miñoso,[15] Nellie Fox,[16] Luis Aparicio,[17] Billy Pierce,[18] and Sherm Lollar.[19] From 1957 to 1965, the Sox were managed by Al López. The Sox finished in the upper half of the American League in eight of his nine seasons, including six years in the top two of the league.[20] In 1959, the White Sox ended the New York Yankees' dominance over the American League, and won their first pennant since the ill-fated 1919 campaign.[21] Despite winning game one of the 1959 World Series 11–0, they fell to the Los Angeles Dodgers in six games.[22]

During the late 1960s and 1970s, the White Sox struggled to win games and attract fans. The team played a total of 20 home games at Milwaukee County Stadium in the 1968 and 1969 seasons. Allyn and Bud Selig agreed to a handshake deal that would give Selig control of the club and move them to Milwaukee, but it was blocked by the American League.[23] Selig instead bought the Seattle Pilots and moved them to Milwaukee, where they would become the Milwaukee Brewers, putting enormous pressure on the American League to place a team in Seattle. A plan was in place for the Sox to move to Seattle and for Charlie Finley to move his Oakland A's to Chicago. However, the city had a renewed interest in the Sox after the 1972 season, and the American League instead added the expansion Seattle Mariners. The 1972 White Sox had the lone successful season of this era, as Dick Allen wound up winning the American League MVP award.[24] Bill Veeck returned as owner of the Sox in 1975, and despite not having much money, they managed to win 90 games in 1977, with a team known as the "South Side Hitmen".

However, the team's fortunes plummeted afterwards, plagued by 90-loss teams and scarred by the notorious 1979 Disco Demolition Night promotion.[25] Veeck was forced to sell the team, rejecting offers from ownership groups intent on moving the club to Denver and eventually agreeing to sell it to Ed DeBartolo, the only prospective owner who promised to keep the White Sox in Chicago. However, DeBartolo was rejected by the owners, and the club was then sold to a group headed by Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn. The Reinsdorf era started off well, with the team winning their first division title in 1983, led by manager Tony La Russa[26] and stars Carlton Fisk, Tom Paciorek, Ron Kittle, Harold Baines, and LaMarr Hoyt.[27] During the 1986 season, La Russa was fired by announcer-turned-general manager Ken Harrelson. La Russa went on to manage in six World Series (winning three) with the Oakland A's and St. Louis Cardinals, ending up in the Hall of Fame as the second-winningest manager of all time.[28]

The White Sox struggled for the rest of the 1980s, as Chicago fought to keep them in town. Reinsdorf wanted to replace the aging Comiskey Park, and sought public funds to do so. When talks stalled, a strong offer was made to move the team to Tampa, Florida.[29] Funding for a new ballpark was approved in an 11th-hour deal by the Illinois State Legislature on June 30, 1988, with the stipulation that it had to be built on the corner of 35th and Shields, across the street from the old ballpark, as opposed to the suburban ballpark the owners had designed.[23] Architects offered to redesign the ballpark to a more "retro" feel that would fit in the city blocks around Comiskey Park; however, the ownership group was set on a 1991 open date, so they kept the old design.[30] The new ballpark opened in 1991 under the name new Comiskey Park. The park, renamed in 2003 as U.S. Cellular Field and in 2016 as Guaranteed Rate Field, underwent many renovations in the early 2000s to give it a more retro feel.

The White Sox were fairly successful in the 1990s and early 2000s, with 12 winning seasons from 1990 to 2005. First baseman Frank Thomas became the face of the franchise, ending his career as the White Sox's all-time leader in runs, doubles, home runs, total bases, and walks.[31] Other major players included Robin Ventura, Ozzie Guillén, Jack McDowell, and Bobby Thigpen.[32] The Sox won the West division in 1993, and were in first place in 1994, when the season was canceled due to the 1994 MLB Strike.

In 2004, Ozzie Guillén was hired as manager of his former team.[33] After finishing second in 2004, the Sox won 99 games and the Central Division title in 2005, behind the work of stars Paul Konerko, Mark Buehrle, A. J. Pierzynski, Joe Crede, and Orlando Hernández.[34] They started the playoffs by sweeping the defending champion Boston Red Sox in the ALDS, and beat the Angels in five games to win their first pennant in 46 years, due to four complete games by the White Sox rotation.[35] The White Sox went on to sweep the Houston Astros in the 2005 World Series, giving them their first World Championship in 88 years.[36]

Guillén had marginal success during the rest of his tenure, with the Sox winning the Central Division title in 2008 after a one-game playoff with the Minnesota Twins.[37] Guillén left the White Sox after the 2011 season and was replaced by former teammate Robin Ventura. The White Sox finished the 2015 season, their 115th in Chicago, with a 76–86 record, a three-game improvement over 2014.[38] The White Sox recorded their 9,000th win in franchise history by the score of 3–2 against the Detroit Tigers on September 21, 2015. Ventura returned in 2016, with a young core featuring José Abreu, Adam Eaton, José Quintana, and Chris Sale.[39] Ventura resigned after the 2016 season, in which the White Sox finished 78–84. Rick Renteria, the 2016 White Sox bench coach, was promoted to the role of manager.

Prior to the start of the 2017 season, the White Sox traded Sale to the Boston Red Sox and Eaton to the Washington Nationals for prospects including Yoán Moncada, Lucas Giolito and Michael Kopech, signaling the beginning of a rebuilding period. During the 2017 season, the White Sox continued their rebuild when they made a blockbuster trade with their crosstown rival, the Chicago Cubs, in a swap that featured the Sox sending pitcher José Quintana to the Cubs in exchange for four prospects headlined by outfielder Eloy Jiménez and pitcher Dylan Cease. This was the first trade between the White Sox and Cubs since the 2006 season.[40]

During the 2018 season, relief pitcher Danny Farquhar suffered a brain hemorrhage while he was in the dugout between innings.[41] Farquhar remained out of action for the rest of the season and just recently got medically cleared to return to baseball, despite some doctors doubting that he would make a full recovery.[42] Also occurring during the 2018 season, the White Sox announced that the club would be the first Major League Baseball team to entirely discontinue use of plastic straws, in ordinance with the "Shedd the Straw" campaign by Shedd Aquarium.[43] The White Sox broke an MLB record during their 100-loss campaign of 2018, but broke the single-season strikeout record in only a year after the Milwaukee Brewers broke the record in the 2017 season.[44] On December 3, 2018, head trainer Herm Schneider retired after 40 seasons with the team; his new role will be as an advisor on medical issues pertaining to free agency, the amateur draft and player acquisition. Schneider will also continue to be a resource for the White Sox training department, including both the major and minor league levels.[45]

On August 25, 2020, Lucas Giolito recorded the 19th no-hitter in White Sox history, and the first since Philip Humber's Perfect Game in 2012. Giolito struck out 13 and threw 74 of 101 pitches for strikes. He only allowed one baserunner, which was a walk to Erik González in the fourth inning. In 2020, the White Sox clinched a playoff berth for the first time since 2008, with a record 35–25 in the pandemic-shortened season, but lost to the Oakland Athletics in three games during the Wild Card Series. The White Sox also made MLB history by being the first team to go undefeated against left-handed pitching, with a 14–0 record.[46] At the end of the season, Renteria and longtime pitching coach Don Cooper were both fired.[47] Jose Abreu became the 4th different White Sox player to win the AL MVP joining Dick Allen, Nellie Fox, and Frank Thomas.[48] During the 2021 offseason, the White Sox brought back Tony La Russa as their manager for 2021.[49] At the age of 76 when hired, La Russa became the oldest active manager in MLB.

On April 14, 2021, pitching against the Cleveland Indians, Carlos Rodon recorded the team's 20th no-hitter. Rodon retired the first 25 batters he faced and was saved by an incredible play at first base by first baseman Jose Abreu to get the first out in the 9th before hitting Roberto Pérez which was the only baserunner Rodon allowed. Rodon struck out seven and threw 75 of 114 pitches for strikes. On June 6, 2021, the White Sox beat the Detroit Tigers 3–0. This also had Tony La Russa winning his 2,764th game as manager passing John McGraw for 2nd on the all-time managerial wins list. On August 12, 2021, the White Sox faced New York Yankees in the first ever Field of Dreams game in Dyersville, Iowa. The White Sox won the game 9–8 on a walk-off two-run Home Run by Tim Anderson. The homer was the 15th walk-off home run against the Yankees in White Sox history; the first being Shoeless Joe Jackson on July 20, 1919, whose character featured in the movie Field of Dreams. On September 23, 2021, the White Sox clinched the American League Central Division for the first time since 2008 against the Cleveland Indians.

In 2024, the White Sox tied a 14-game losing streak, then proceeded to have a 21-game losing streak from July 10 to August 5. They became the 7th team all time, and the first since the 1988 Baltimore Orioles to lose 20 consecutive games.[50] On September 1, the White Sox set a new franchise record for losses at 107 following a 2–0 loss to the New York Mets. They are also the first team since the 1965 Mets to have 3 separate 10 or more game losing streaks in one season. [51] On September 27, the White Sox lost their 121st game of the season, surpassing the 1962 Mets for the most losses in modern MLB history.[52]

Ballparks

editIn the late 1980s, the franchise threatened to relocate to Tampa Bay (as did the San Francisco Giants), but frantic lobbying on the part of the Illinois governor James R. Thompson and state legislature resulted in approval (by one vote) of public funding for a new stadium.[53] Designed primarily as a baseball stadium (as opposed to a "multipurpose" stadium), the new Comiskey Park (redubbed U.S. Cellular Field, often nicknamed "The Cell", in 2003 and Guaranteed Rate Field in 2016, after mortgage company Guaranteed Rate) was built in a 1960s style, similar to Dodger Stadium and Kauffman Stadium. There were ideas for other stadium designs[54] submitted to bring a more neighborhood feel, but ultimately they were not selected. The park opened in 1991 to positive reaction, with many praising its wide-open concourses, excellent sight lines, and natural grass (unlike other stadiums of the era, such as Rogers Centre in Toronto). The park's inaugural season drew 2,934,154 fans — at the time, an all-time attendance record for any Chicago baseball team.

In recent years, money accrued from the sale of naming rights to the field has been allocated for renovations to make the park more aesthetically appealing and fan-friendly. Notable renovations of early phases included reorientation of the bullpens parallel to the field of play (thus decreasing slightly the formerly symmetrical dimensions of the outfield); filling seats in up to and shortening the outfield wall; ballooning foul-line seat sections out toward the field of play; creating a new multitiered batter's eye, allowing fans to see out through one-way screens from the center-field vantage point, and complete with concession stand and bar-style seating on its "fan deck"; and renovating all concourse areas with brick, historic murals, and new concession stand ornaments to establish a more friendly feel. The stadium's steel and concrete were repainted dark gray and black. In 2016, the scoreboard jumbotron was replaced with a new Mitsubishi Diamondvision HDTV screen.[55]

The top quarter of the upper deck was removed in 2004, and a black wrought-metal roof was placed over it, covering all but the first eight rows of seats. This decreased seating capacity from 47,098 to 40,615; 2005 also had the introduction of the Scout Seats, redesignating (and reupholstering) 200 lower-deck seats behind home plate as an exclusive area, with seat-side waitstaff and a complete restaurant located underneath the concourse. The most significant structural addition besides the new roof was 2005's FUNdamentals Deck, a multitiered structure on the left-field concourse containing batting cages, a small Tee Ball field, speed pitch, and several other children's activities intended to entertain and educate young fans with the help of coaching staff from the Chicago Bulls/Sox Training Academy. This structure was used during the 2005 American League playoffs by ESPN and the Fox Broadcasting Company as a broadcasting platform.

Designed as a seven-phase plan, the renovations were completed before the 2007 season with the seventh and final phase. The most visible renovation in this final phase was replacing the original blue seats with green seats. The upper deck already had new green seats put in before the beginning of the 2006 season. Beginning with the 2007 season, a new luxury-seating section was added in the former press box. This section has amenities similar to those of the Scout Seats section. After the 2007 season, the ballpark continued renovation projects despite the phases being complete. In July 2019, the White Sox extended the netting to the foul pole.

Previous ballparks

editThe St. Paul Saints first played their games at Lexington Park.[56] When they moved to Chicago's Armour Square neighborhood, they began play at the South Side Park. Previously a cricket ground, the park was located on the north side of 39th Street (now called Pershing Road) between South Wentworth and South Princeton Avenues.[57] Its massive dimensions yielded few home runs, which was to the advantage of the White Sox's Hitless Wonders teams of the early 20th century.[58]

After the 1909 season, the Sox moved five blocks to the north to play in the new Comiskey Park, while the 39th Street grounds became the home of the Chicago American Giants of the Negro leagues. Billed as the Baseball Palace of the World, it originally held 28,000 seats and eventually grew to hold over 50,000.[59] It became known for its many odd features, such as the outdoor shower and the exploding scoreboard. When it closed after the 1990 season, it was the oldest ballpark still in Major League Baseball.

Spring-training ballparks

editThe White Sox have held spring training in:[60]

- Excelsior Springs, Missouri (1901–1902)

- Mobile, Alabama (1903);

- Marlin Springs, Texas (1904)

- New Orleans (1905–1906)

- Mexico City, Mexico (1907)

- Los Angeles (1908)

- San Francisco (Recreation Park, 1909–1910)

- Mineral Wells, Texas (1911, 1916–1919)

- Waco, Texas (1912, 1920);

- Paso Robles, California (1913–1915)

- Waxahachie, Texas (1921)

- Seguin, Texas (1922–1923)

- Winter Haven, Florida. (1924)

- Shreveport, Louisiana (1925–1928)

- Dallas (1929)

- San Antonio (1930–1932)

- Pasadena, California (1933–1942, 1946–1950)

- French Lick, Indiana (1943–1944)

- Terre Haute, Indiana (1945)

- Palm Springs, California (Palm Springs Stadium, 1951)

- El Centro, California (1952–1953);

- Tampa, Florida (1954–1959, Plant Field, 1954, Al Lopez Field 1955–1959)

- Sarasota, Florida (1960–1997; Payne Park Ed Smith Stadium 1989–97).

- Tucson, Arizona (Tucson Electric Park, 1998–2008, Cactus League, shared with Arizona Diamondbacks)[61]

- Phoenix, Arizona (Camelback Ranch, 2009–present)

On November 19, 2007, the cities of Glendale and Phoenix, Arizona, broke ground on a new Cactus League spring-training facility. Camelback Ranch, the $76 million, two-team facility, is the home of both the White Sox and the Los Angeles Dodgers for their spring training, featuring state-of-the-art baseball facilities and an over 10,000-seat stadium.[62] The facility is also home to amenities such as 118,000 sq ft. of clubhouse space, 13 full fields, citrus groves, and a large lake and river system stocked with fish running throughout the complex.[63]

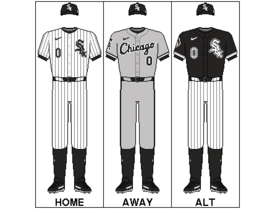

Logos and uniforms

editOver the years, the White Sox have become noted for many of their uniform innovations and changes. In 1960, they became the first team in the major sports to put players' last names on jerseys for identification purposes.

In 1912, the White Sox debuted a large "S" in a Roman-style font, with a small "O" inside the top loop of the "S" and a small "X" inside the bottom loop. This is the logo associated with the 1917 World Series championship team and the 1919 Black Sox. With a couple of brief interruptions, the dark-blue logo with the large "S" lasted through 1938 (but continued in a modified block style into the 1940s). Through the 1940s, the White Sox team colors were primarily navy blue trimmed with red.

The White Sox logo in the 1950s and 1960s (actually beginning in the 1949 season) was the word "SOX" in Gothic script, diagonally arranged, with the "S" larger than the other two letters. From 1949 through 1963, the primary color was black (trimmed with red after 1951). This is the logo associated with the Go-Go Sox era.

In 1964, the primary color went back to navy blue, and the road uniforms changed from gray to pale blue. In 1971, the team's primary color changed from royal blue to red, with the color of their pinstripes and caps changing to red. The 1971–1975 uniform included red socks.

In 1976, the team's uniforms changed again. The team's primary color changed back from red to navy. The team based their uniforms on a style worn in the early days of the franchise, with white jerseys worn at home, and blue on the road. The team brought back white socks for the last time in team history. The socks featured a different stripe pattern every year. The team also had the option to wear blue or white pants with either jersey. Additionally, the team's "SOX" logo was changed to a modern-looking "SOX" in a bold font, with "CHICAGO" written across the jersey. Finally, the team's logo featured a silhouette of a batter over the words "SOX".

The new uniforms also featured collars and were designed to be worn untucked — both unprecedented. Yet by far, the most unusual wrinkle was the option to wear shorts, which the White Sox did for the first game of a doubleheader against the Kansas City Royals in 1976. The Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League had previously tried the same concept, but it was also poorly received. Apart from aesthetic issues, as a practical matter, shorts are not conducive to sliding, due to the likelihood of significant abrasions.

Upon taking over the team in 1980, new owners Eddie Einhorn and Jerry Reinsdorf announced a contest where fans were invited to create new uniforms for the White Sox. The winning entries, submitted by a fan, had the word "SOX" written across the front of the jersey in the same font as the cap, inside of a large blue stripe trimmed with red. The red and blue stripes were also on the sleeves, and the road jerseys were gray to the home whites. In those jerseys, the White Sox won 99 games and the AL West championship in 1983, the best record in the majors.

After five years, those uniforms were retired and replaced with a more basic uniform that had "White Sox" written across the front in script, with "Chicago" on the front of the road jersey. The cap logo was also changed to a cursive "C", although the batter logo was retained for several years.

For a midseason 1990 game at Comiskey Park, the White Sox appeared once in a uniform based on that of the 1917 White Sox. They then switched their regular uniform style once more. In September, for the final series at the old Comiskey Park, the White Sox rolled out a new logo, a simplified version of the 1949–63 Gothic "SOX" logo. They also introduced a uniform with black pinstripes, also similar to the Go-Go Sox era uniform. The team's primary color changed back to black, this time with silver trim. The team also introduced a new sock logo—a white silhouette of a sock centered inside a white outline of a baseball diamond—which appeared as a sleeve patch on the away uniform until 2010 (switched to the "SOX" logo in 2011), and on the alternate black uniform since 1993. With minor modifications (i.e., occasionally wearing vests, black game jerseys), the White Sox have used this style ever since.

During the 2012 and 2013 seasons, the White Sox wore their throwback uniforms at home every Sunday, starting with the 1972 red-pinstriped throwback jerseys worn during the 2012 season, followed by the 1982–86 uniforms the next season. In the 2014 season, the "Winning Ugly" throwbacks were promoted to full-time alternate status, and are now worn at home on Sundays. In one game during the 2014 season, the Sox paired their throwbacks with a cap featuring the batter logo instead of the wordmark "SOX"; this is currently their batting-practice cap prior to games in the throwback uniforms. After the 2023 season, the Sunday throwback uniforms were quietly taken off the team's uniform rotation.

In 2021, to commemorate the Field of Dreams game, the White Sox wore special uniforms honoring the 1919 team. That same year, the White Sox wore "City Connect" alternate uniforms introduced by Nike, featuring an all-black design with silver pinstripes, and "Southside" wordmark in front.

Awards and accolades

editWorld Series championships

edit| Season | Manager | Regular season record | World Series opponent | World Series record | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1906 | Fielder Jones | 93–58 | Chicago Cubs | 4–2 | [64] | |

| 1917 | Pants Rowland | 100–54 | New York Giants | 4–2 | [65] | |

| 2005 | Ozzie Guillén | 99–63 | Houston Astros | 4–0 | [66] | |

| 3 World Championships | ||||||

American League championships

editNote: American League Championship Series began in 1969

| Season | Manager | Regular season record | AL Runner-Up/ALCS opponent | Games ahead/ALCS record | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | Charles Comiskey | 82–53 | Milwaukee Brewers | 2.0 | [67] | |

| 1901 | Clark Griffith | 83–53 | Boston Americans | 4.0 | [68] | |

| 1906 | Fielder Jones | 93–58 | New York Highlanders | 3.0 | [64] | |

| 1917 | Pants Rowland | 100–54 | Boston Red Sox | 9.0 | [65] | |

| 1919 | Kid Gleason | 88–52 | Cleveland Indians | 3.5 | [69] | |

| 1959 | Al López | 94–60 | Cleveland Indians | 5.0 | [70] | |

| 2005 | Ozzie Guillén | 99–63 | Los Angeles Angels | 4–1 | [66] | |

| 7 American League Championships | ||||||

Award winners

edit- 1959 – Nellie Fox

- 1972 – Dick Allen

- 1993 – Frank Thomas

- 1994 – Frank Thomas

- 2020 - Jose Abreu

- 1959 – Early Wynn (MLB)

- 1983 – LaMarr Hoyt (AL)

- 1993 – Jack McDowell (AL)

- 1951 – Orestes "Minnie" Miñoso (Sporting News)

- 1956 – Luis Aparicio

- 1963 – Gary Peters

- 1966 – Tommie Agee

- 1983 – Ron Kittle

- 1985 – Ozzie Guillén

- 2014 – José Abreu

- 1983 – Tony La Russa

- 1990 – Jeff Torborg

- 1993 – Gene Lamont

- 2000 – Jerry Manuel

- 2005 – Ozzie Guillén

Team captains

edit- Willie Kamm 1927–1928[71]

- Art Shires 1929[72]

- Luke Appling 1930–1950

- Ozzie Guillén 1990–1997

- Carlton Fisk 1990–1993

- Paul Konerko 2006–2014

Retired numbers

editThe White Sox have retired a total of 12 jersey numbers: 11 worn by former White Sox and number 42 in honor of Jackie Robinson.[73]

|

Luis Aparicio's No. 11 was issued at his request for 11-time Gold Glove winner shortstop Omar Vizquel (because No. 13 was used by manager Ozzie Guillén; Vizquel, like Aparicio and Guillen, play(ed) shortstop and all share a common Venezuelan heritage). Vizquel played for team in 2010 and 2011.[74]

Also, Harold Baines had his No. 3 retired in 1989; it has since been 'unretired' 3 times in each of his subsequent returns.

Out of circulation, but not retired

edit- 6: Since Charley Lau's death in 1984, no White Sox player or coach (except Lau disciple Walt Hriniak, the Chicago White Sox's hitting coach from 1989 to 1995) has worn his No. 6 jersey, although it has not been officially retired.

- 13: Since Ozzie Guillén left as manager of the White Sox, no Sox player or coach has worn his No. 13 jersey, although it is not officially retired.

Baseball Hall of Famers

edit| Chicago White Sox Hall of Famers |

|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum |

|

Ford C. Frick Award recipients

edit| Chicago White Sox Ford C. Frick Award recipients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Players and personnel

editRoster

editFront office and key personnel

edit| Chicago White Sox key personnel | |||||

| Chairman | Jerry Reinsdorf | ||||

| Senior Executive Vice President | Howard Pizer | ||||

| General Manager | Chris Getz | ||||

| Assistant General Manager | Jeremy Haber | ||||

| Senior Director of Baseball Operations | Dan Fabian | ||||

| Director of Baseball Analytics | Matt Koenig | ||||

| Director of Baseball Operations | Daniel Zien | ||||

| Senior Vice President, Administration | Tim Buzard | ||||

| Senior Vice President, Stadium Operations | Terry Savarise | ||||

| Senior Vice President, Communications | Scott Reifert | ||||

| Senior Vice President, Sales and Marketing | Brooks Boyer | ||||

| Vice President, General Counsel | John Corvino | ||||

| Head Groundskeeper | Roger Bossard | ||||

| Spanish Language Interpreter | Billy Russo [75] | ||||

| Public Address Announcer | Gene Honda | ||||

| Organist | Lori Moreland | ||||

- Source:[76]

Culture

editNicknames

editThe White Sox were originally known as the White Stockings, a reference to the original name of the Chicago Cubs.[77] To fit the name in headlines, local newspapers such as the Chicago Tribune abbreviated the name alternatively to Stox and Sox.[78] Charles Comiskey would officially adopt the White Sox nickname in the club's first years, making them the first team to officially use the "Sox" name. The Chicago White Sox are most prominently nicknamed "the South Siders", based on their particular district within Chicago. Other nicknames include the synonymous "Pale Hose";[79] "the ChiSox", a combination of "Chicago" and "Sox", used mostly by the national media to differentiate them between the Boston Red Sox (BoSox); and "the Good Guys", a reference to the team's one-time motto "Good guys wear black", coined by broadcaster Ken Harrelson. Most fans and Chicago media refer to the team as simply "the Sox". The Spanish language media sometimes refer to the team as Medias Blancas for "White Socks."

Several individual White Sox teams have received nicknames over the years:

- The 1906 team was known as the Hitless Wonders due to their .230 batting average, worst in the American League.[80] Despite their hitting woes, the Sox would beat the crosstown Cubs for their first world title.

- The 1919 White Sox are known as the Black Sox after eight players were banned from baseball for fixing the 1919 World Series.

- The 1959 White Sox were referred to as the Go-Go White Sox due to their speed-based offense. The period from 1951 to 1967, in which the White Sox had 17 consecutive winning seasons, is sometimes referred to as the Go-Go era.[81]

- The 1977 team was known as the South Side Hitmen as they contended for the division title after finishing last the year before.

- The 1983 White Sox became known as the Winning Ugly White Sox in response to Texas Rangers manager Doug Rader's derisive comments that the White Sox "...weren't playing well. They're winning ugly."[82] The Sox went on to win the 1983 American League West division on September 17.

Mascots

editFrom 1961 until 1991, lifelong Chicago resident Andrew Rozdilsky performed as the unofficial yet popular mascot "Andy the Clown" for the White Sox at the original Comiskey Park. Known for his elongated "Come on you White Sox" battle cry, Andy got his start after a group of friends invited him to a Sox game in 1960, where he decided to wear his clown costume and entertain fans in his section. That response was so positive that when he won free 1961 season tickets, he decided to wear his costume to all games.[83] Comiskey Park ushers eventually offered free admission to Rozdilsky.[84] Starting in 1981, the new ownership group led by Jerry Reinsdorf introduced a twosome, called Ribbie and Roobarb, as the official team mascots, and banned Rozdilsky from performing in the lower seating level. Ribbie and Roobarb were very unpopular, as they were seen as an attempt to get rid of the beloved Andy the Clown.[85]

In 1988, the Sox got rid of Ribbie and Roobarb; Andy the Clown was not permitted to perform in the new Comiskey Park when it opened in 1991. In the early 1990s, the White Sox had a cartoon mascot named Waldo the White Sox Wolf that advertised the "Silver and Black Pack", the team's kids' club at the time. The team's current mascot, SouthPaw, was introduced in 2004 to attract young fans.[1][86]

Fight and theme songs

editNancy Faust became the White Sox organist in 1970, a position she held for 40 years.[87] She was one of the first ballpark organists to play pop music, and became known for her songs playing on the names of opposing players (such as Iron Butterfly's "In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida" for Pete Incaviglia).[88] Her many years with the White Sox established her as one of the last great stadium organists. Since 2011, Lori Moreland has served as the White Sox organist.[89]

Similar to the Boston Red Sox with "Sweet Caroline" (and two songs named "Tessie"), and the New York Yankees with "Theme from New York, New York", several songs have become associated with the White Sox over the years. They include:

- "Let's Go Go Go White Sox" by Captain Stubby and the Buccaneers – A tribute to the "Go-Go White Sox" of the late 1950s, this song serves as the unofficial fight song of the White Sox. In 2005, scoreboard operator Jeff Szynal found a record of the song and played it for a "Turn Back the Clock" game against the Los Angeles Dodgers, whom the Sox played in the 1959 World Series.[90] After catcher A. J. Pierzynski hit a walk-off home run, they kept the song around, as the White Sox went on to win the 2005 World Series.

- "Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye" by Steam – Organist Nancy Faust played this song during the 1977 pennant race when a Kansas City Royals pitcher was pulled, and it became an immediate hit with White Sox fans.[88] Faust is credited with making the song a stadium anthem and saving it from obscurity. To this day, the song remains closely associated with the White Sox, who play it when the team forces a pitching change, and occasionally on Sox home runs and victories.[91]

- "Sweet Home Chicago" – The Blues Brothers version of this Robert Johnson blues standard is played after White Sox games conclude.

- "Thunderstruck" by AC/DC – One of the most prominent songs for the White Sox player introductions, the team formed a bond with AC/DC's hit song in 2005 and it has since become a staple at White Sox home games.[92] The White Sox front office has tried replacing the song several times in an attempt to "shake things up", but White Sox fans have always showed their displeasure with new songs and have successfully gotten the front office to keep the fan-favorite song.[93]

- "Don't Stop Believin'" by Journey – During the 2005 season, the White Sox adopted the 1981 Journey song as their rally song after catcher A.J. Pierzynski suggested it be played through U.S. Cellular Field's speakers. During the 2005 World Series, the White Sox invited Journey's lead singer, Steve Perry, to Houston and allowed him to celebrate with the team on the field after the series-clinching sweep of the Houston Astros.[94] Perry also performed the song with members of the team during the team's victory parade in Chicago.

- "Don't Stop the Party" by Pitbull – After every White Sox home run at Guaranteed Rate Field, Pitbull's "Don't Stop the Party" played over the loudspeakers.

Rivalries

editThis section possibly contains original research. (August 2008) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

Crosstown Classic

editThe Chicago Cubs are the crosstown rivals of the White Sox, a rivalry that some made fun of prior to the White Sox's 2005 title because both of them had extremely long championship droughts. The nature of the rivalry is unique; with the exception of the 1906 World Series, in which the White Sox upset the favored Cubs, the teams never met in an official game until 1997, when interleague play was introduced. In the intervening time, the two teams sometimes met for exhibition games. The White Sox currently led the regular-season series 48–39, winning the last four consecutive seasons. The BP Crosstown Cup was introduced in 2010 and the White Sox won the first three seasons (2010–2012) until the Cubs first won the Cup in 2013 by sweeping the season series. The White Sox won the Cup the next season and retained the Cup the following two years (series was a tie - Cup remains with defending team in the event of a tie). The Cubs took back the Cup in 2017. Two series sweeps have occurred since interleague play began, both by the Cubs in 1998 and 2013.

An example of this volatile rivalry is the game played between the White Sox and the Cubs at U.S. Cellular Field on May 20, 2006. White Sox catcher A. J. Pierzynski was running home on a sacrifice fly by center fielder Brian Anderson and smashed into Cubs catcher Michael Barrett, who was blocking home plate. Pierzynski lost his helmet in the collision, and slapped the plate as he rose. Barrett stopped him, and after exchanging a few words, punched Pierzynski in the face, causing a melee to ensue. Brian Anderson and Cubs first baseman John Mabry got involved in a separate confrontation, although Mabry was later determined to be attempting to be a peacemaker. After 10 minutes of conferring following the fight, the umpires ejected Pierzynski, Barrett, Anderson, and Mabry. As Pierzynski entered his dugout, he pumped his arms, causing the sold-out crowd at U.S. Cellular Field to erupt in cheers. When play resumed, White Sox second baseman Tadahito Iguchi blasted a grand slam to put the White Sox up 5–0 on their way to a 7–0 win over their crosstown rivals.[95] While other major league cities and metropolitan areas have two teams co-exist, all of the others feature at least one team that began playing there in 1961 or later, whereas the White Sox and Cubs have been competing for their city's fans since 1901.

Historical

editA historical regional rival was the St. Louis Browns. Through the 1953 season, the two teams were located fairly close to each other (including the 1901 season when the Browns were the Milwaukee Brewers), and could have been seen as the American League equivalent of the Cardinals–Cubs rivalry, being that Chicago and St. Louis have for years been connected by the same highway (U.S. Route 66 and now Interstate 55). The rivalry has been somewhat revived at times in the past, involving the Browns' current identity, the Baltimore Orioles, most notably in 1983.

The current Milwaukee Brewers franchise were arguably the White Sox's main and biggest rival, due to the proximity of the two cities (resulting in large numbers of White Sox fans who would regularly be in attendance at the Brewers' former home, Milwaukee County Stadium), and with the teams competing in the same American League division for the 1970 and 1971 seasons and then again from 1994 to 1997. The rivalry has since cooled off, however, when the Brewers moved to the National League in 1998. However, with the start of the 2023 season, all teams will play each other at least once a year, leading to the Brewers-White Sox series to return on a yearly basis.

Divisional

editMinnesota Twins

editThe rivalry between the White Sox and Minnesota Twins developed during the 2000s, as the two teams consistently battled for the AL Central Crown. The Twins won the division in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006, and 2009, with the Sox winning in 2000, 2005, and 2008, many of those years their rival was the division runner-up. The teams met in the 2008 American League Central tie-breaker game, which was necessitated by the two clubs finishing the season with identical records. The White Sox won this game 1–0 on a Jim Thome home run. The rivalry re-emerged in the 2020s, with the Twins winning the AL Central in 2020 by a single game over the White Sox and Cleveland Indians, and the Sox and Twins have continued to compete for the division title since that point.

Detroit Tigers

editThe series between the White Sox and Detroit Tigers is one of the oldest active rivalries in the league today. Both teams joined the American League in 1901 after being charter members of the original Western League.[96] Both have actively played one another annually for over 120 seasons. As is often the case between professional sports teams located Chicago or Detroit; there usually exists a rivalry as such with the Bulls-Pistons rivalry of the NBA. Despite playing one another for over 2,200 games; both teams have yet to meet in the postseason in their 122-year series.[97][98][99]

Community Outreach

editIn 1990, then new White Sox owners Eddie Einhorn and Jerry Reinsdorf began Chicago White Sox Charities, a 501(c) (3) charitable organization that is the team's philanthropic arm, donating over $27 million over time to a plethora of Chicago organizations. White Sox Charities began centering on early childhood literacy programs, then expanded to focusing on encouraging high school graduation and college matriculation so the team can monitor its success. It also supports children at risk as well as promotes wellness and health.[100]

Home attendance

editComiskey Park

edit| Home attendance at Comiskey Park | ||||

| Year | Total attendance | Game average | League rank | Ref |

| 2000 | 1,947,799 | 24,047 | 20th | [101] |

| 2001 | 1,766,172 | 21,805 | 26th | [102] |

| 2002 | 1,676,911 | 20,703 | 23rd | [103] |

U.S. Cellular Field

edit| Home attendance at U.S. Cellular Field | ||||

| Year | Total attendance | Game average | League rank | Ref |

| 2003 | 1,939,524 | 23,945 | 21st | [104] |

| 2004 | 1,930,537 | 23,834 | 21st | [105] |

| 2005 | 2,342,833 | 28,924 | 17th | [106] |

| 2006 | 2,957,414 | 36,511 | 9th | [107] |

| 2007 | 2,684,395 | 33,141 | 15th | [108] |

| 2008 | 2,500,648 | 30,496 | 16th | [109] |

| 2009 | 2,284,163 | 28,200 | 16th | [110] |

| 2010 | 2,194,378 | 27,091 | 17th | [111] |

| 2011 | 2,001,117 | 24,705 | 20th | [112] |

| 2012 | 1,965,955 | 24,271 | 24th | [113] |

| 2013 | 1,768,413 | 21,832 | 24th | [114] |

| 2014 | 1,650,821 | 20,381 | 28th | [115] |

| 2015 | 1,755,810 | 21,677 | 27th | [116] |

| 2016 | 1,746,293 | 21,559 | 26th | [117] |

Guaranteed Rate Field

edit| Home attendance at Guaranteed Rate Field | ||||

| Year | Total attendance | Game average | League rank | Ref |

| 2017 | 1,629,470 | 20,117 | 27th | [118] |

| 2018 | 1,608,817 | 19,862 | 25th | [119] |

| 2019 | 1,649,775 | 20,622 | 24th | [120] |

| 2020 | –[d] | – | – | [121] |

| 2021 | 1,596,385[e] | 19,708 | 13th | [124] |

| 2022 | 2,009,359 | 24,087 | 19th | [125] |

| 2023 | 1,669,628 | 20,613 | 24th | [126] |

Broadcasting

editRadio

editThe White Sox did not sell exclusive rights for radio broadcasts from radio's inception until 1944, instead having local stations share rights for games, and after WGN (720) was forced to abdicate their rights to the team in the 1943 after 16 seasons due to children's programming commitments from their network, Mutual.[127][128] The White Sox first granted exclusive rights in 1944, and bounced between stations until 1952, when they started having all games broadcast on WCFL (1000).[129] Throughout this period of instability, one thing remained constant, the White Sox play-by-play announcer, Bob Elson. Known as the "Commander", Elson was the voice of the Sox from 1929 until his departure from the club in 1970.[130] In 1979, he was the recipient of the Ford Frick Award, and his profile is permanently on display in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

After the 1966 season, radio rights shifted from WCFL to WMAQ (670). An NBC-owned and -operated station until 1988 when Westinghouse Broadcasting purchased it after NBC's withdrawal from radio, it was the home of the Sox until the 1996 season, outside of a team nadir in the early '70s, where it was forced to broker time on suburban La Grange's WTAQ (1300) and Evanston's WEAW-FM (105.1) to have their play-by-play air in some form (though WEAW transmitted from the John Hancock Center, FM radio was not established as a band for sports play-by-play at the time),[127] and a one-season contract on WBBM (780) in 1981. After Elson's retirement in 1970, Harry Caray began his tenure as the voice of the White Sox, on radio and on television. Although best remembered as a broadcaster for the rival Cubs, Caray was very popular with White Sox fans, pining for a "cold one" during broadcasts.[131] Caray often broadcast from the stands, sitting at a table set up amid the bleachers. It became a badge of honor among Sox fans to "Buy Harry a beer..." By game's end, one would see a large stack of empty beer cups beside his microphone. This only endeared him to fans that much more. In fact, he started his tradition of leading the fans in the singing of "Take Me Out To The Ballgame" with the Sox.[132] Caray, alongside color analyst Jimmy Piersall, was never afraid to criticize the Sox, which angered numerous Sox managers and players, notably Bill Melton and Chuck Tanner. He left to succeed Jack Brickhouse as the voice of the Cubs in 1981, where he became a national icon.

The White Sox shifted through several announcers in the 1980s, before hiring John Rooney as play-by-play announcer in 1989. In 1992, he was paired with color announcer Ed Farmer. In 14 seasons together, the duo became a highly celebrated announcing team, even being ranked by USA Today as the top broadcasting team in the American League.[133] Starting with Rooney and Farmer's fifth season together, Sox games returned to the 1000 AM frequency for the first time in 30 years. By then, it had become the ESPN owned and operated WMVP. The last game on WMVP was game 4 of the 2005 World Series, with the White Sox clinching their first World Series title in 88 years. That also was Rooney's last game with the Sox, as he left to join the radio broadcast team of the St. Louis Cardinals.

In 2006, radio broadcasts returned to 670 AM, this time on the sports radio station WSCR owned by CBS Radio (WSCR took over the 670 frequency in August 2000 as part of a number of shifts among CBS Radio properties to meet market ownership caps). Ed Farmer became the play-by-play man after Rooney left, joined in the booth by Chris Singleton from 2006 to 2007 and then Steve Stone in 2008. In 2009, Darrin Jackson became the color announcer for White Sox radio, where he remains today.[134] Farmer and Jackson were joined by pregame/postgame host Chris Rogney.

The Chicago White Sox Radio Network currently has 18 affiliates in three states.[135] As of recently, White Sox games are also broadcast in Spanish with play-by-play announcer Hector Molina joined in the booth by Billy Russo.[136] Formerly broadcasting on ESPN Deportes Radio via WNUA, games are now broadcast in Spanish on WRTO (1200).[137][138]

In the 2016 season, the play-by-play rights shifted to Cumulus Media's WLS (890) under a five-year deal, when WSCR acquired the rights to Cubs games after a one-year period on WBBM. However, by all counts, the deal was a disaster for the White Sox, as WLS's declining conservative talk format, associated ratings, and management/personnel issues (including said hosts barely promoting the team and its games), and a signal that is weak in the northern suburbs and into Wisconsin, was not a good fit for the team. Cumulus also had voluminous financial issues, and by the start of 2018, looked to both file Chapter 11 bankruptcy and restructure their play-by-play deals or depart them, both with local teams and nationally through their Westwood One/NFL deal.[139][127]

The White Sox and Tribune Broadcasting (which has since merged with Nexstar Media Group) then announced a three-year deal for WGN Radio to become the White Sox flagship as of February 14, 2018, just in time for spring training. Ed Farmer and Darrin Jackson continued to be on play-by-play, with Andy Masur taking over pregame/postgame duties.[140] Ed Farmer died suddenly on April 1, 2020, a long-term battle with polycystic kidney disease, but the team waited to announce his successor due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the uncertainty of the 2020 season going forward.[141] On June 30 with the season's structure announced, Masur was confirmed as Farmer's successor for the season.[142]

Under Nexstar's new management, WGN decided to pursue a thriftier programming direction, and made no moves to renew the deal at the end of the 2020 season. The team thus returned to WMVP (now managed by Good Karma Brands, which also owns Brewers flagship WTMJ) for a multi-year agreement to start with the 2021 season.[143] In a surprising turn of events, WMVP and the team announced on December 4, 2020, that Len Kasper, the longtime television play-by-play voice of the Cubs, would move to the South Side and become the radio play-by-play voice of the White Sox. The agreement has flexibility which allows Kasper to do some television games on NBC Sports Chicago on days when Jason Benetti has other national commitments.[144]

Television

editWhite Sox games appeared sporadically on television throughout the first half of the 20th century, most commonly announced by Jack Brickhouse on WGN-TV (channel 9). Starting in 1968, Jack Drees took play-by-play duties as the Sox were broadcast on WFLD (channel 32).[145] After 1972, Harry Caray (joined by Jimmy Piersall in 1977) began double duty as a TV and radio announcer for the Sox, as broadcasts were moved to channel 44, WSNS-TV, from 1972 to 1980, followed by one year on WGN-TV.

Don Drysdale became the play-by-play announcer in 1982, as the White Sox began splitting their broadcasts between WFLD and the new regional cable television network, Sportsvision. Ahead of its time, Sportsvision had a chance to gain huge profits for the Sox. However, few people would subscribe to the channel after being used to free-to-air broadcasts for many years, along with Sportsvision being stunted by the city of Chicago's wiring for cable television taking much longer than many markets because of it being an area where over-the-air subscription services were still more popular, resulting in the franchise losing around $300,000 a month.[146] While this was going on, every Cubs game was on WGN, with Harry Caray becoming the national icon he never was with the White Sox. The relatively easy near-national access to Cubs games versus Sox games in this era, combined with the popularity of Caray and the Cubs being owned by the Tribune Company, is said by some to be the main cause of the Cubs' advantage in popularity over the Sox.

Three major changes to White Sox broadcasting occurred in 1989-1991: in 1989, with the city finally fully wired for cable service, Sportsvision was replaced by SportsChannel Chicago (itself eventually turning into Fox Sports Net Chicago), which varied over its early years as a premium sports service and basic cable channel. In 1990, over-the-air broadcasts shifted back to WGN. And in 1991, Ken Harrelson became the play-by-play announcer of the White Sox.[147] One of the most polarizing figures in baseball, "Hawk" has been both adored and scorned for his emotive announcing style. His history of calling out umpires has earned him reprimands from the MLB commissioner's office, and he has been said to be the most biased announcer in baseball.[148] However, Harrelson has said that he is proud of being "the biggest homer in baseball", saying that he is a White Sox fan like his viewers.[149] The team moved from FSN Chicago to the newly launched NBC Sports Chicago in March 2005, as Jerry Reinsdorf looked to control the rights for his team rather than sell rights to another party; Reinsdorf holds a 40% interest in the network, with 20% of that interest directly owned by the White Sox corporation.

Previously, White Sox local television broadcasts were split between two channels: the majority of games were broadcast on cable by NBC Sports Chicago, and remaining games were produced by WGN Sports and were broadcast locally on WGN-TV. WGN games were also occasionally picked up by local stations in Illinois, Iowa, and Indiana. In the past, WGN games were broadcast nationally on the WGN America superstation, but those broadcasts ended after the 2014 season as WGN America began its transition to a standard cable network.[150] WGN Sports-produced White Sox games not carried by WGN-TV were carried by WCIU-TV (channel 26) until the 2015 season, when they moved to MyNetworkTV station WPWR (channel 50).[151] That arrangement ended on September 1, 2016, when WGN became an independent station.

Prior to 2016, the announcers were the same no matter where the games were broadcast: Harrelson provided play-by-play, and Steve Stone provided color analysis since 2009.[152] Games that are broadcast on NBC Sports Chicago feature pregame and postgame shows, hosted by Chuck Garfein with analysis from Bill Melton and occasionally Frank Thomas. In 2016, the team announced an official split of the play-by-play duties, with Harrelson calling road games and the Crosstown Series and Jason Benetti calling home games.[153] In 2017, the team announced that the 2018 season will be Harrelson's final in the booth. He will call 20 games over the course of the season, after which Benetti will take over full-time play-by-play duties.[154]

On January 2, 2019, the White Sox (along with the Chicago Bulls and Chicago Blackhawks) agreed to an exclusive multiyear deal with NBC Sports Chicago, ending the team's broadcasts on WGN-TV following the 2019 season.[155]

Prior to the 2024 season, the White Sox named John Schriffen as its new lead television play-by-play announcer, after Benetti departed to join the Detroit Tigers broadcast team.[156]

Minor league affiliates

editThe Chicago White Sox farm system consists of six minor league affiliates.[157]

| Class | Team | League | Location | Ballpark | Affiliated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triple-A | Charlotte Knights | International League | Charlotte, North Carolina | Truist Field | 1999 |

| Double-A | Birmingham Barons | Southern League | Birmingham, Alabama | Regions Field | 1986 |

| High-A | Winston-Salem Dash | South Atlantic League | Winston-Salem, North Carolina | Truist Stadium | 1997 |

| Single-A | Kannapolis Cannon Ballers | Carolina League | Kannapolis, North Carolina | Atrium Health Ballpark | 2001 |

| Rookie | ACL White Sox | Arizona Complex League | Glendale, Arizona | Camelback Ranch | 2014 |

| DSL White Sox | Dominican Summer League | Boca Chica, Santo Domingo | Baseball City Complex | 1999 |

Silver Chalice subsidiary

editSilver Chalice is a digital and media investment subsidiary of the White Sox with Brooks Boyer as CEO.[158]

Silver Chalice was co-founded by Jerry Reinsdorf, White Sox executive Brooks Boyer, Jason Coyle and John Burris in 2009.[158][159] The company first invested in 120 Sports, a digital sports channel, that launched in June 2014.[159] Chalice then partnered with IMG on Campus Insiders, a college sports digital channel, in 2015.[158] These two efforts merged with Sinclair Broadcasting Group's American Sports Network into the new multi-platform network Stadium in September 2017.[160]

In May 2023, Sinclair sold its controlling interest in Stadium to Silver Chalice.[161][162]

Notes

edit- ^ The team's official colors are black and silver, according to the team's mascot (Southpaw)'s official website.[1]

- ^ Select games only.

- ^ The American League was still considered a minor league in 1900, subject to the National Agreement with the older National League.

- ^ No spectators were allowed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- ^ Due to the aforementioned pandemic, Guaranteed Rate Field had capacity restrictions until June 10; 20% capacity from the beginning of the season to June 10,[122] and finally full capacity on June 11.[123]

References

edit- ^ a b "About Southpaw". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ "Logos and Uniforms". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Ritchie, Matthew (September 26, 2023). "How an MLB rebrand shook up the hip-hop world". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved December 10, 2023.

Drawing on the classic Yankees "pinstripes" uniforms, they adopted white jerseys with black pinstripes for home games, and utilized the silver and black color scheme for the away and alternate jerseys.

- ^ "Stathead.com".

- ^ "Chicago White Sox Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball Reference. Baseball Info Solutions. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Bova, George (February 26, 2002). "Sox Fans' Guide to Sox Uniforms". FlyingSock.Com. White Sox Interactive. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "1901, after having won in the minor league American League in 1900. American League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Stezano, Martin (October 24, 2012). "6 Things You May Not Know About the World Series". History. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "1906 World Series". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "1917 World Series". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "The Black Sox". Chicago Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "J. Louis Comiskey". Baseballbiography.com. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ "Retired Numbers". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "All-Time Owners". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Minnie Miñoso". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Nellie Fox". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Luis Aparicio". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Billy Pierce". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Sherm Lollar". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Al López". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "1959 Chicago White Sox season". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "1959 World Series". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ a b Bova, George. "Save Our Sox!". FlyingSock.com. White Sox Interactive. Archived from the original on December 22, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ "Dick Allen". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Vettel, Phil. "Steve Dahl's Disco Demolition at Comiskey Park". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Tony La Russa". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "1983 Chicago White Sox Season". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Garfein, Chuck (February 4, 2013). "Hawk Opens Up on Firing La Russa". CSN Chicago. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Sullivan, Paul Francis (June 21, 2011). "The Franchise moves that never happened". The Hardball Times. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Bova, George. "A Conversation with Phillip Bess". FlyingSock.com. White Sox Interactive. Archived from the original on March 8, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Frank Thomas". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "1993 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Guillen Back with White Sox as Manager". ESPN. November 5, 2003. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ "2005 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "2005 ALCS". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "White Sox end 88-year drought, sweep Astros to win World Series". ESPN. October 27, 2005. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Merkin, Scott (October 1, 2008). "White Sox claim AL Central Crown". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ van Schouwen, Daryl (October 4, 2015). "White Sox blanked in fitting finish to 2015". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- ^ "2014 Chicago White Sox season". Baseball Reference. Sport Reference. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "White Sox, Cubs cold war is over with Jose Quintana trade". USA TODAY. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "White Sox Reliever Danny Farquhar Has Brain Hemorrhage During Game". The New York Times. April 21, 2018. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ "Danny Farquhar: Clears final hurdle". CBSSports.com. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ Kane, Colleen. "White Sox are 1st MLB team to ditch single-use plastic straws". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ "White Sox batters break season strikeout record". ESPN.com. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "Herm Schneider to become head athletic trainer emeritus in 2019 after 40 seasons". MLB.com. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "White Sox go undefeated against left-handed pitching". Janice Scurio. September 29, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ Duber, Vinnie. "Sox part ways with Renteria and Cooper, will have new manager in 2021". NBC Sports Chicago.

- ^ "Abreu overcome by first career MVP Award". MLB.com. November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ "White Sox announce Tony La Russa as team's new manager". October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ "White Sox losing streak: Chicago becomes 7th MLB team, first since 1988, to lose 20 games in a row". August 4, 2024. Retrieved August 4, 2024.

- ^ "White Sox fall to Mets, set franchise record with 107th loss". September 1, 2024. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Nadkarni, Rohan (September 27, 2024). "Chicago White Sox lose 121st game this season, most in baseball history, passing the 1962 New York Mets with 120 losses". NBC News. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ Kass, John (May 12, 1988). "Thompson: Sox Vow To Stay If Bill Passes". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Perry, Dayn (April 10, 2018). "The White Sox ballpark in Chicago that never was and could have changed history". CBS Sports. CBS Interactive. CBS Sports Digital. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Kane, Colleen (January 28, 2016). "White Sox believe scoreboard project 'will change game experience'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Thornley, Stew (2004). "Twin Cities Ballparks". stewthornley.net. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Cellular Field History". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ Healey, Paul. "South Side Park". Project Ballpark. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ Fletcher, David J. "Never on a Friday". Chicago Baseball Museum. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ "Chicago White Sox Spring Training".

- ^ "Chicago White Sox: Spring Training History". Spring Training Online. August Publications. Archived from the original on September 4, 2005. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ "Let's Play Ball!". Glendale AZ. June 26, 2007. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ "About Camelback Ranch". MLB. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ a b "1906 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "1917 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "2005 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ "1900 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "1901 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ "1919 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ "1959 Chicago White Sox". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ^ "Major League Squads Work Out Under Hot Sun; Holdouts Coming In". Daily Illini. March 2, 1927. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ Lynch, Mike. "Art Shires". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ "Retired Numbers". Chicago White Sox. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ "White Sox Un-Retire Aparicio's Number, Vizquel to Wear No. 11 During 2010 Season". Press release. WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. February 8, 2010. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ "His childhood dream turned into a career with the Chicago White Sox". NPR.org.

- ^ "Chicago White Sox Front Office". Official Site of the Chicago White Sox. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ "Chicago Cubs Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ Engber, Daniel (October 25, 2015). "X Marks The Baseball team". Explainer. Slate. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ DeFord, Frank (May 18, 2005). "The Finest Nickname in Baseball". National Public Radio. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ "1906: The Hitless Wonders". This Great Game. Archived from the original on April 3, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ Secter, Bob. "The 1959 'Go-Go' White Sox and the air-raid sirens". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ Evans, Sean (April 25, 2012). "The 25 Greatest Moments in White Sox History". Complex. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Singer, Stacey (September 24, 1995). "Andrew Rozdilsky, 77, Clown for Sox". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Ley, Tom (January 14, 2014). "A Brief History of Terrible Chicago Mascots". Deadspin. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ "White Sox History: The sad story of Ribbie and Roobarb". South Side Sox. SBNation. March 16, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Padilla, Doug (January 23, 2014). "Sox: 'No grief about our mascot'". ESPNChicago.com. ESPN Internet Ventures, LLC. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Crouse, Karen (September 17, 2010). "Ballpark Farewell, Played Adagio". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Vickery, Hal. "Flashing Back with Nancy Faust". FlyingSock.com. White Sox Interactive. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Austen, Jake (June 30, 2011). "An organist transplant for the White Sox". Chicago Reader. Sun-Times Media. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Theiser, Kelly (October 18, 2005). "Go-Go song revival a hit with fans". White Sox official website. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on April 13, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Brown, David (October 24, 2011). "Goodbye, Paul Leka: Writer of sports anthem 'Na Na Hey Hey' dies". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ bravewords.com. "AC/DC - 'Thunderstruck' Builds Fever Pitch For Chicago White Sox". bravewords.com. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Samuelson, Kristin. "Cris Quintana brings back 'Thunderstruck' after Twitter shade from White Sox fans". RedEye Chicago. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "ESPN: The Worldwide Leader in Sports". ESPN.com. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ "Cubs' Barrett slugs Pierzynski, leads to melee". ESPN.com. May 20, 2006. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ "Midwest Masscre: A Look at The Chicago/Detroit Rivalry". Bleacher Report.

- ^ Stavenhagen, Cody. "The Tigers-White Sox drama might just foreshadow a budding AL Central rivalry". The Athletic.

- ^ "Detroit Tigers seek 'competitive rivalry' with Chicago White Sox for AL Central".

- ^ "Tigers' Javier Baez sends White Sox stern message as AL Central rivalry reconvenes". April 9, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Darrell J. (Spring 2017). "Giving Back". Leaders. New York NY: Leaders Magazine LLC.

- ^ "2000 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2001 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2002 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2003 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2004 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2005 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2006 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2007 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2008 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2009 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2010 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2011 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2012 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2013 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2014 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2015 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2016 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2017 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2018 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2019 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "2020 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Reichard, Kevin (March 9, 2021). "Which MLB ballparks are hosting fans in 2021? Here's the list". Ballpark Digest. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ "Wrigley Field, Guaranteed Rate Field set for 100% capacity". June 3, 2021. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "2021 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ "2022 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ "2023 Major League Baseball Attendance & Team Age". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c Castle, George (February 14, 2018). "WGN-Radio and 720 signal best possible 2018 home for White Sox". Chicago Baseball Museum. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ "All-Time Broadcasters". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on February 26, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Right on Q: A brief history of the White Sox on the radio". South Side Sox. SB Nation. May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ "1979 Ford Frick Award Winner Bob Elson". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "1989 Ford Frick Award Winner Harry Caray". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Bohn, Matt. "Harry Caray". SABR.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Gardner, Steve (July 26, 2005). "Rooney, Farmer give White Sox AL's top radio team". USA Today. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ "Broadcasters". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Radio Affiliates". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on February 25, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "White Sox Announce new Spanish radio broadcasters". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. March 28, 2012. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ "2015 Broadcast Schedule". Official Site of the Chicago White Sox. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ Hart, Rob (May 17, 2014). "Right on Q: A brief history of the White Sox on the radio". South Side Sox. SBNation. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Rosenthal, Phil (January 18, 2018). "WLS-AM parent company asks court to end 'unprofitable' White Sox, Bulls deals". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Feder, Robert (February 14, 2018). "Play ball! WGN Radio picks up White Sox". Robert Feder blog. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Merkin, Scott (April 2, 2020). "White Sox announcer Ed Farmer, 70, dies". MLB.com. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ Rosenthal, Phil (June 30, 2020). "Andy Masur: New Chicago White Sox radio voice - Chicago Tribune". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Feder, Robert (November 12, 2020). "Done deal: White Sox radio broadcasts return to ESPN 1000". Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Feder, Robert (December 4, 2020). "Cubs TV announcer Len Kasper named radio voice of White Sox on ESPN 1000". Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "All-Time Broadcasters- Television". WhiteSox.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on February 26, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "White Sox History: The story of SportsVision". South Side Sox. SB Nation. November 30, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Edelman, Alexander. "Ken Harrelson". SABR.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Selig reprimands Harrelson for rant against umpire". Chicago Tribune. June 1, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (September 26, 2012). "How Biased Is Your Announcer?". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Feder, Robert (December 15, 2014). "WGN America comes home to Chicago". Robert Feder. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Sherman, Ed (February 19, 2015). "White Sox add WPWR-Ch. 50 to station rotation". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ Berger, Ralph. "Steve Stone". SABR.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ Van Schouwen, Daryl (June 24, 2016). "White Sox adding Jason Benetti to play-by-play team". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Kane, Colleen (May 31, 2017). "Ken 'Hawk' Harrelson to retire in 2018 after 'greatest ride of my life'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ "NBC Sports Chicago Announces New Pact With White Sox, Bulls, and Blackhawks". WMAQ-TV. January 2, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ "White Sox name John Schriffen new television play-by-play voice". MLB.com. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Chicago White Sox Minor League Affiliates". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c Sherman, Ed (April 21, 2014). "Executive Profile: Brooks Boyer". Chicago Tribune. pp. 1–3. Retrieved August 17, 2016.