The Arabian leopard (Panthera pardus nimr) is the smallest leopard subspecies. It was described in 1830 and is native to the Arabian Peninsula, where it was widely distributed in rugged hilly and montane terrain until the late 1970s. Today, the population is severely fragmented and thought to decline continuously. In 2008, an estimated 45–200 individuals in three isolated subpopulations were restricted to western Saudi Arabia, Oman and Yemen. However, as of 2023, it is estimated that 100–120 in total remain, with 70-84 mature individuals, in Oman and Yemen, and it is possibly extinct in Saudi Arabia. The current population trend is suspected to be decreasing.[1]

| Arabian leopard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leopard at Ein Gedi, Israel | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. p. nimr

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera pardus nimr | |

| |

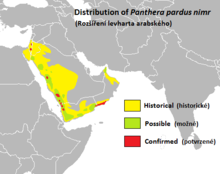

| Distribution of the Arabian leopard | |

| Synonyms | |

|

P. p. jarvisl Pocock, 1932 | |

Taxonomic history

editFelis pardus nimr was the scientific name proposed by Wilhelm Hemprich and Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg in 1830 for a leopard from Arabia.[2] Panthera pardus jarvisi, proposed by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1932, was based on a leopard skin from the Sinai Peninsula.[3]

In the early 1990s, a phylogeographic analysis was carried out based on tissue samples from Asian and African leopards. P. p. jarvisi was provisionally grouped with Panthera pardus tulliana, as tissue samples were not available.[4] Genetic analysis of a single wild leopard from South Arabia appeared most closely related to the African leopard, and Molecular biologists tentatively proposed in 2001 to group the Sinai leopard with the Arabian leopard, as again tissue samples were not available.[5]

Characteristics

editThe Arabian leopard's fur varies from pale yellow to deep golden, tawny or grey and is patterned with rosettes.[6] Males have a total length of 182–203 cm (72–80 in) including 77–85 cm (30–33 in) long tails and weigh about 30 kg (66 lb); females are 160–192 cm (63–76 in) long including 67–79 cm (26–31 in) long tails and weigh around 20 kg (44 lb).[7] It is the smallest leopard subspecies.[8] It is however the largest cat in the Arabian Peninsula.[9][10]

Distribution and habitat

editThe geographic range of the Arabian leopard is poorly understood but generally considered to be limited to the Arabian Peninsula, including Egypt's Sinai Peninsula.[11] It lives in mountainous uplands and hilly steppes, but seldom moves to open plains, desert or coastal lowlands.[10] Since the late 1990s, leopards were not recorded in Egypt.[7] One individual was killed in the Elba Protected Area in 2014.[12]

Until the late 1960s, the Arabian leopard was widely distributed in the mountains along both the coasts of the Red Sea and Arabian Sea.[9] In Saudi Arabia, leopard habitat is estimated to have decreased by around 90% since the beginning of the 19th century. Of 19 reports obtained from informants between 1998 and 2003, only four are confirmed including sightings in one location in the Hijaz Mountains and three locations in the Asir Mountains, with the most recent record in 2002 south of Biljurashi. No leopard was recorded during a camera trapping survey conducted from 2002 to 2003. Although the leopard is officially protected in the country, its remaining range is not encompassed by protected areas.[13]

In the United Arab Emirates, the Arabian leopard was first sighted in 1949 by Wilfred Thesiger in Jebel Hafeet.[14] The exact status of the leopard in the country is unclear. It is either extinct or very rare in the eastern region, with occasional sightings being reported in places like Wadi Wurayah.[15] Before the end of the 20th century, sightings were reported in the areas of Jebel Hafeet and Al-Hajar Mountains.[7][16]

In Oman, leopards were reported to have occurred in the Hajar Mountains until the late 1970s.[7] The largest confirmed sub-population inhabits the Dhofar Mountains in the country's southeast. In the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve, 17 individual adult leopards were identified between 1997 and 2000 using camera traps.[17] Leopards were also sighted in the Musandam Peninsula,[7] particularly Ras Musandam.[9] The home range of Arabian leopards in this reserve is roughly estimated at 350 km2 (140 sq mi) for males and 250 km2 (97 sq mi) for females.[16] The Dhofar mountain range is considered the best habitat for leopards in the country. This rugged terrain provides shelters, shade and trapped water, and harbors a wide variety of prey species, in particular in escarpments and narrow wadis.[18]

In Yemen, leopards formerly ranged in all mountainous areas of the country, including the western and southern highlands eastwards to the border with Oman. Since the early 1990s, leopards are considered rare and close to extinction due to direct persecution by local people and depletion of wild prey.[19]

There was a small population in Israel's Negev desert, estimated at 20 individuals in the late 1970s.[20] Leopards were hunted until the early 1960s. By 2002, fewer than 11 isolated individuals were estimated to survive. Six males, three females and two unsexed individuals were identified in the country, based on genetic analysis of 268 scats collected. About five individuals were thought to survive in the Judaean Desert as of 2005.[21] The last wild leopard in the Negev desert was sighted near Sde Boker in 2007, which was in a poor and weak shape; and the last leopard in the northern Arabah Valley was sighted in 2010–11.[22]

In Jordan, the last confirmed sighting of a leopard dates to 1987.[23]

Ecology and behaviour

editArabian leopards are predominantly nocturnal, but are sometimes also seen in daylight.[10] They seem to concentrate on small to medium prey species, and usually store carcasses of large prey in caves or lairs but not in trees.[24] Scat analyses revealed that the main prey species comprise Arabian gazelle, Nubian ibex, Cape hare, rock hyrax, porcupine, Ethiopian hedgehog, small rodents, birds, and insects. Since local people reduced ungulates to small populations, leopards are forced to alter their diet to smaller prey and livestock such as goats, sheep, donkeys and young camels.[13]

Information about ecology and behaviour of Arabian leopards in the wild is very limited.[16] A leopard from the Judean desert is reported to have come into heat in March. After a gestation period of 13 weeks, females give birth to two to four cubs in a cave amidst boulders or in a burrow.[10]

Leopard cubs are born with closed eyes that open four to nine days later.[25] Captive-born Arabian leopard cubs emerged from their den for the first time at the age of one month.[26] Cubs are weaned at the age of about three months, and remain with their mother for up to two years.[25]

Threats

editThree confirmed separate subpopulations remain on the Arabian Peninsula with fewer than an estimated 200 leopards.[27][28] The Arabian leopard is threatened by habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation; prey depletion caused by unregulated hunting; trapping for the illegal wildlife trade and retaliatory killing in defense of livestock.[7][13]

The leopard population has decreased drastically in Arabia as shepherds and villagers kill leopards in retaliation for attacks on livestock. In addition, hunting of leopard prey species such as hyrax and ibex by local people and habitat fragmentation, especially in the Sarawat Mountains, made the continued survival of the leopard population uncertain. Other reasons for killing leopards are for personal satisfaction and pride, traditional medicine and hides. Some leopards are killed accidentally when eating poisoned carcasses intended for Arabian wolf and striped hyena.[29] Among the products sold in the tent city of Mina, Saudi Arabia after the Hajj of 2010, skins of Arabian leopards that were poached in Yemen were offered.[30]

The leopard population in Saudi Arabia is affected by the decrease of natural prey species so that leopards increasingly prey on livestock. Local people therefore consider leopards a threat and kill them either by using poison or snares. The leopard population is close to extinction in the country.[31]

The Israeli West Bank Barrier, built by the Israeli government in the mid-2000s, disrupts the migration of all terrestrial land animals between Israel and Palestine, therefore reducing animals' natural habitats and causing gene pools to be significantly shallower, which results in inbreeding and infertility.[32]

In the 1950s, the Arabian leopard population was already decreasing drastically due to habitat degradation and fragmentation, and killing of leopards and prey species.[33]

Conservation

editThe 4,500 km2 (1,700 sq mi) Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve was established in 1997 after camera trap records of leopards were obtained; in the following decade, 17 individual adult leopards and one cub were identified.[17] Leopards were also radio-collared and tracked in this Nature Reserve.[34]

At least ten wild leopards were live-captured in Yemen since the early 1990s and sold to zoos; some have been placed in conservation breeding centers in the UAE and Saudi Arabia.[19]

A detailed study of leopard distribution and habitat requirement is needed for the management of the species. The ecological information needed include data on feeding behavior, range use and reproduction. This information is of great importance to the survival of the species. There are many sites already surveyed and considered to be suitable for preservation for leopards in the plan adopted by the national commission for wildlife conservation and development. These areas include Jebel Fayfa, Jebel Al-Qahar, Jebel Shada, which has already been gazetted as a protected area, Jebel Nees, Jebel Wergan, Jebel Radwa and Harrat Uwayrid. The formal establishment of some of these areas is now urgent.[1]

A successful conservation strategy must promote the awareness of the importance of leopard conservation, employing the media and perhaps other sources for basic education programs. The support and involvement of people living close to leopard habitats are vital in such efforts. This is true not only because they might affect the conservation of the leopard in one way or another, but also because they depend on their livestock which could be killed occasionally by leopards. Although it is not always practical, compensation for lost livestock from leopard predation should be considered.[35]

Revenue from sources such as hunting rights and ecotourism, services such as roads and school employment in protected areas would encourage local residents to participate in leopard conservation. Furthermore, well-managed protected areas will ensure the continued survival of the species until other factors enhancing its survival become effective. Public awareness, fruitful consideration of the needs of local people and ecological studies may take years to be useful.[36]

In Yemen, efforts are underway to conserve leopards at two sites, including Hawf Protected Area.[37] In Saudi Arabia, authorities have undertaken efforts to create Sharaan Nature Reserve, a wildlife sanctuary for the leopard in the area of Al-`Ula.[38][39]

In captivity

editThe first Arabian leopards were captured in southern Oman and registered in the studbook in 1985. Captive breeding was initiated in 1995 at the Oman Mammal Breeding Centre and is operated at a regional level on the Arabian Peninsula. Since 1999, the regional studbook is coordinated and managed by personnel of the Breeding Centre for Endangered Arabian Wildlife, Sharjah.[40] As of 2010[update], nine institutions participated in the breeding programme and kept 42 males, 32 females, and three unsexed leopards, of which 19 were wild caught. This captive population comprised 14 founders that have an unequal number of descendants.[41] In 2016, the leopards and other fauna were transferred from the breeding centre in Sharjah to Al Hefaiyah Conservation Centre in the eastern area of Kalba.[42]

In Yemen, leopards were kept at Ta'izz and Sana'a Zoos.[43] Two cubs were born on 26 April 2019 at the Prince Saud Al-Faisal Wildlife Research Center in Ta'if.[44]

Arabian Leopard Day

editIn February 2022, Saudi Council of Ministers declared February 10 as the "Arabian Leopard Day" in an effort to protect the species and raise awareness of their conservation status.[45] In June 2023, The United Nations voted to adopt a resolution to officially designate February 10 as an international day for Arabian Leopards.[46]

On the second Arabian Leopard Day, which took place in February 2023, The Royal Commission of Al Ula created a $25 million fund to promote conservation efforts and signed a 10-year deal with Panthera worth $20 million.[47]

See also

edit- Leopard subspecies

References

edit- ^ a b c Al Hikmani, H.; Spalton, A.; Zafar-ul Islam, M.; al-Johany, A.; Sulayem, M.; Al-Duais, M.; Almalki, A. (2024) [amended version of 2023 assessment]. "Panthera pardus ssp. nimr". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2024: e.T15958A259040222. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Hemprich, W.; Ehrenberg, C. G. (1830). "Felis, pardus?, nimr". In Dr. C. G. Ehrenberg (ed.). Symbolae Physicae, seu Icones et Descriptiones Mammalium quae ex Itinere per Africam Borealem et Asiam Occidentalem Friderici Guilelmi Hemprich et Christiani Godofredi Ehrenberg. Decas Secunda. Zoologica I. Mammalia II. Berolini: Officina Academica. pp. Plate 17.

- ^ Pocock, R. I. (1932). "The Leopards of Africa". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 543−591. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1932.tb01085.x.

- ^ Miththapala, S.; Seidensticker, J.; O'Brien, S. J. (1996). "Phylogeographic Subspecies Recognition in Leopards (P. pardus): Molecular Genetic Variation". Conservation Biology. 10 (4): 1115–1132. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10041115.x.

- ^ Uphyrkina, O.; Johnson, W. E.; Quigley, H.; Miquelle, D.; Marker, L.; Bush, M. & O'Brien, S. (2001). "Phylogenetics, genome diversity and origin of modern leopard, Panthera pardus" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 10 (11): 2617–2633. Bibcode:2001MolEc..10.2617U. doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01350.x. PMID 11883877. S2CID 304770. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-28. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ Seidensticker, J. & Lumpkin, S. (1991). Great Cats. London: Merehurst.

- ^ a b c d e f Spalton, J. A.; Al Hikmani, H. M. (2006). "The Leopard in the Arabian Peninsula – Distribution and Subspecies Status" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 1): 4–8. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Biquand, S. (1990). "Short review of the status of the Arabian leopard, Panthera pardus nimr, in the Arabian Peninsula". In Shoemaker, A. (ed.). International Leopard Studbook. Columbia: Riverbanks Zoological Park. pp. 8−10.

- ^ a b c Nader, I. A. (1989). "Rare and endangered mammals of Saudi Arabia" (PDF). In Abu-Zinada, A. H.; Goriup, P. D.; Nader, I. A (eds.). Wildlife conservation and development in Saudi Arabia. 3. Riyadh: National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development Publishing. pp. 226–228.

- ^ a b c d Harrison, D. L. & Bates, P. J. J. (1991). The mammals of Arabia (PDF). Vol. 354. Sevenoaks, UK: Harrison Zoological Museum. pp. 167–170.

- ^ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 73–75.

- ^ Soultan, A.; Attum, O.; Hamada, A.; Hatab, E.-B.; Ahmed, S. E.; Eisa, A.; Sharif, I. A.; Nagy, A.; Shohdi, W. (2017). "Recent observation for leopard Panthera pardus in Egypt". Mammalia. 81 (1): 115–117. doi:10.1515/mammalia-2015-0089. S2CID 90676105.

- ^ a b c Judas, J.; Paillat, P.; Khoja, A.; Boug, A. (2006). "Status of the Arabian leopard in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 1): 11–19.

- ^ Thesiger, W. (1949). "A Further Journey across the Empty Quarter". The Geographical Journal. 113 (113): 21–44. Bibcode:1949GeogJ.113...21T. doi:10.2307/1788902. JSTOR 1788902.

- ^ "Arabian Tahr gets royal protection". WWF. 2009. Archived from the original on 2018-09-13. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ^ a b c Edmonds, J.-A.; Budd, K. J.; Al Midfa, A. & Gross, C. (2006). "Status of the Arabian Leopard in United Arab Emirates" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 1): 33–39.

- ^ a b Spalton, A.; Hikmani, H. D. a.; Willis, D. & Said, A. S. B. (2006). "Critically endangered Arabian leopards Panthera pardus nimr persist in the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve, Oman". Oryx. 40 (3): 287–294. doi:10.1017/S0030605306000743.

- ^ Mazzolli, M. (2009). "Arabian Leopard Panthera pardus nimr status and habitat assessment in northwest Dhofar, Oman (Mammalia: Felidae)". Zoology in the Middle East 47: 3–12. doi:10.1080/09397140.2009.10638341. S2CID 53510526.

- ^ a b Al Jumaily, M.; Mallon, D. P.; Nasher, A. K. & Thowabeh, N. (2006). "Status Report on Arabian Leopard in Yemen". Cat News. Special Issue 1: 20–25.

- ^ Nowell, K. & Jackson, P. (1996). "Leopard Panthera pardus". Wild cats: status survey and conservation action plan. Gland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. Archived from the original on 2013-02-23. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ Perez, I.; Geffen, E. & Mokady, O. (2006). "Critically Endangered Arabian leopards Panthera pardus nimr in Israel: estimating population parameters using molecular scatology". Oryx. 40 (3): 295–301. doi:10.1017/s0030605306000846.

- ^ Granit, B. (2016). "Once there were Leopards". BirdLife Israel.

- ^ Qarqaz, M. & Abu Baker, M. (2006). "The Leopard in Jordan". Cat News. Special Issue 1: 9–10.

- ^ Kingdon, J. (1990). Arabian Mammals. London: Academic Press Ltd.

- ^ a b Sunquist, M. E.; Sunquist, F. (2002). Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-77999-8.

- ^ Budd, K. (2001). "Arabian Leopards: New Hope is Born". Arabian Wildlife. 2000/2001: 8–9.

- ^ Breitenmoser, U. (2006). 7th Conservation Workshop for the Fauna of Arabia 19–22 February: Workshop report. Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: Breeding Center for Endangered Arabian Wildlife.

- ^ Mallon, D.P.; Budd, K. (2011). "Arabian Leopard Panthera pardus nimr (Hemprich & Ehrenberg, 1833)" (PDF). Regional Red List status of carnivores in the Arabian Peninsula. Gland and Sharjah, UAE: IUCN. pp. 13–15.

- ^ Environment and Protected Areas Authority (2002). Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) for the threatened fauna of Arabia's Mountain Habitat. Final Report. Sharjah, UAE: EPAA.

- ^ Anonymous (2010). "Wildlife skins for sale after Haj – Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Wildlife Times. 27: 13–14.

- ^ Zafar-ul Islam, M.; Boug, A.; Judas, J.; As-Shehri, A. (2018). "Conservation challenges for the Arabian Leopard (Panthera pardus nimr) in the Western Highlands of Arabia". Biodiversity. 19 (3–4): 188–197. Bibcode:2018Biodi..19..188Z. doi:10.1080/14888386.2018.1507008. S2CID 134163948.

- ^ "The environmental impacts of the Israeli West Bank Barrier" by Michael L. Thomas and Karen E. Jenni.

- ^ Sanborn, C.; Hoogstral, H. (1953). "Some mammals of Yemen and their parasites". Fieldiana Zoology. 34: 229–.

- ^ Rushby, K. (2011). Saving the Leopard (Documentary). Qatar: Al Jazeera.

- ^ Anderson, D.; Grove, A. (1989). Conservation of Africa: People, Politics and Practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bailey, T. N. (1993). The African leopard: Ecology and Behavior of a Solitary Felid. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ "Arabian leopard conservation project in Yemen". Rewilding Foundation. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Shirka, H. (2019). "Al Ula conservation project can help Arabian leopards come roaring back". The National. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Al-Khudair, D. (2019). "$20 million deal signed to save Arabian leopard population". Arab News. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Edmonds, J. A.; Budd, K. J.; Vercammen, P. & al Midfa, A. (2006). "History of the Arabian leopard Captive Breeding Programme". Cat News. Special Issue 1: 40–43.

- ^ Budd, J.; Leus, K. (2011). "The Arabian Leopard Panthera pardus nimr conservation breeding programme". Zoology in the Middle East. 54 (Supplement 3): 141–150. doi:10.1080/09397140.2011.10648905.

- ^ "Sharjah's new wildlife centre opens to tourists". Sharjah Update. 2016. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ De Haas van Dorsser, F. J.; Thowabeh, N. S.; Al Midfa, A. A.; Gross, C. (2001). Health status of zoo animals in Sana'a and Ta'izz, Republic of Yemen (PDF) (Report). Sana'a, Yemen: Breeding Centre for Endangered Arabian Wildlife, Sharjah; Environment Protection Authority. pp. 66–69. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- ^ "Successful birth of Arabian leopard cubs 'new beacon of hope' in Saudi bid to save species from extinction: Culture minister". Arab News. 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Read, Johanna (2022-02-09). "It's Arabian Leopard Day And AlUla, Saudi Arabia Is Working To Rewild The Endangered Species". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ KOSSAIFY, EPHREM (2023-06-22). "UN recognition of Arabian Leopard Day a 'major triumph for KSA,' conservationist says". Arab News. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ "Arabian Leopard Day: Saudi Arabia's $25m fund will rewild critically-endangered species". The National News. 2023-02-09. Retrieved 2024-01-19.