The History of Sir Charles Grandison, commonly called Sir Charles Grandison, is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson first published in February 1753. The book was a response to Henry Fielding's The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, which parodied the morals presented in Richardson's previous novels.[1] The novel follows the story of Harriet Byron who is pursued by Sir Hargrave Pollexfen. After she rejects Pollexfen, he kidnaps her, and she is only freed when Sir Charles Grandison comes to her rescue. After his appearance, the novel focuses on his history and life, and he becomes its central figure.

Background

editThe exact relationship between Fielding's The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling and Richardson's The History of Sir Charles Grandison cannot be known, but the character Charles Grandison was designed as a morally "better" hero than the character Tom Jones. In 1749, a friend asked Richardson "to give the world his idea of a good man and fine gentleman combined".[2]: 140–2 Richardson hesitated to begin such a project, and he did not work on it until he was prompted the next year (June 1750) by Anne Donnellan and Miss Sutton, who were "both very intimate with one Clarissa Harlowe: and both extremely earnest with him to give them a good man".[2]: 142 Near the end of 1751, Richardson sent a draft of the novel to Miss Donnellan, and the novel was being finalised in the middle of 1752.[2]: 144

While Thomas Killingbeck, a compositor, and Peter Bishop, a proofreader, were working for Richardson in his print shop during 1753, Richardson discovered that printers in Dublin had copies of The History of Sir Charles Grandison and began printing the novel before the English edition was to be published. Richardson suspected that they were involved with the unauthorized distribution of the novel and promptly fired them. Immediately following the firing, Richardson wrote to Lady Bradshaigh, 19 October 1753: "the Want of the same Ornaments, or Initial Letters [factotums], in each Vol. will help to discover them [if exported into England], although they should put the Booksellers Names that I have affixed. I have got some Friends to write down to Scotland, to endeavour to seize their Edition, if offered to be imported".[3]: 26, 251–2 There were four Dublin presses used to make unauthorized copies of the novel, but none of them were able to add the ornaments that could effectively mimic Richardson's own. However, there were still worries about the unlicensed copies, and Richardson relied on seven additional printers to speed up the production of Grandison.[3]: 29, 252

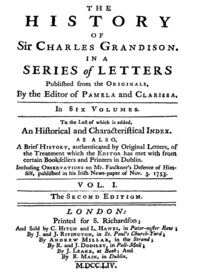

In November 1753, Richardson ran an ad in The Gentleman's Magazine to announce the "History of Sir Charles Grandison: in a Series of Letters published from the Originals, – By the Editor of Pamela and Clarissa, London: Printed for S. Richardson, and sold by Dodsley in Pall Mall and others."[2]: 145 The first four volumes were published on 13 November 1753 and the next two volumes appeared in December. The final volume was published in March to complete a seven volume series while a six volume set was simultaneously published.[2]: 146 Richardson held the sole copyright to Grandison, and, after his death, twenty-fourth shares of Grandison were sold for 20 pounds each.[3]: 90 Posthumous editions were published in 1762 (including revisions by Richardson) and 1810.[1]

Plot summary

editAs with his previous novels, Richardson prefaced the novel by claiming to be merely the editor, saying, "How such remarkable collections of private letters fell into the editor's hand he hopes the reader will not think it very necessary to enquire".[2]: 146 However, Richardson did not keep his authorship secret and, on the prompting of his friends like Samuel Johnson, dropped this framing device from the second edition.[2]: 146

The novel begins with the character of Harriet Byron leaving the house of her uncle, George Selby, to visit Mr. and Mrs. Reeves, her cousins, in London. She is an orphan who was educated by her grandparents, and, though she lacks parents, she is heir to a fortune of fifteen thousand pounds, which causes many suitors to pursue her. In London, she is pursued by three suitors: Mr. Greville, Mr. Fenwick, and Mr. Orme. This courtship is followed by more suitors: Mr. Fowler, Sir Rowland Meredith, and Sir Hargrave Pollexfen. The final one, Pollexfen, pursues Byron vigorously, which causes her to criticise him over a lack of morals and decency of character. However, Pollexfen does not end his pursuits of Byron until she explains that she could never receive his visits again.

Pollexfen, unwilling to be without Byron, decides to kidnap her while she attended a masquerade ball at the Haymarket. She is then imprisoned at Lisson Grove with the support of a widow and two daughters. While he keeps her prisoner, Pollexfen makes it clear to her that she shall be his wife, and that anyone who challenges that will die by his hand. Byron attempts to escape from the house, but this fails. To prevent her from trying to escape again, Pollexfen transports Byron to his home at Windsor. However, he is stopped at Hounslow Heath, where Charles Grandison hears Byron's pleas for help and immediately attacks Pollexfen. After this rescue, Grandison takes Byron to Colnebrook, the home of Grandison's brother-in-law, the "Earl of L.".

After Pollexfen recovers from the attack, he sets out to duel Grandison. However, Grandison refuses on the grounds that dueling is harmful to society. After explaining why obedience to God and society are important, Grandison wins Pollexfen over and obtains his apology to Byron for his actions. She accepts his apology, and he follows with a proposal to marriage. She declines because she, as she admits, is in love with Grandison. However, a new suitor, the Earl of D, appears, and it emerges that Grandison promised himself to an Italian woman, Signorina Clementina della Porretta. As Grandison explains, he was in Italy years before and rescued the Barone della Porretta and a relationship developed between himself and Clementina, the baron's only daughter. However, Grandison could not marry her, as she demanded that he, an Anglican Protestant, become a Catholic, and he was unwilling to do so.

After he left, she grew ill out of despair, and the Porrettas were willing to accept his religion, if he would return and make Clementina happy once more. Grandison, feeling obligated to do what he can to restore Clementina's happiness, returns to Italy; however, Clementina determines she can never marry a "heretic", and so Grandison returns to England and Harriet who accepts him. They are married. Shortly after their marriage, they receive news from the Poretta family that Clementina has fled Italy to avoid their further pressuring her to marry the Count of Belvedere, one of her suitors. The family believes that she has fled to England. Sir Charles finds her and shelters her while her family arrives in England to reconcile with her. Sir Charles negotiates a reconciliation on the terms that the family will leave it up to Clementina, without further pressure or urging, whether she will marry on the condition that she will abandon her plans to join a nunnery. While she is staying in England, Clementina becomes good friends with Harriet.

At the end of the novel, both of Sir Charles' sisters have recently had healthy babies. Sir Charles vivacious sister Charlotte's marriage has improved because she is showing her husband more respect and is excelling in her role as a mother, something she had originally dreaded. It is suggested that Harriet is pregnant. The Poretta family returns to Italy with Clementina saying she will take a year to collect her thoughts and then will decide whether to marry the Count of Belvedere. Sir Charles and Harriet say they will visit Italy in a year (presumably after Harriet has given birth). The novel ends with the death of Sir Hargrave Pollenfax, who dies miserably of wounds he suffered while behaving with iniquity toward another woman. He laments throwing his life away through immoral behavior and leaves Harriet a large amount of his estate to make up for his abuse of her. Thus, everyone is accorded their just deserts.

In a "Concluding Note" to Grandison, Richardson writes: "It has been said, in behalf of many modern fictitious pieces, in which authors have given success (and happiness, as it is called) to their heroes of vicious if not profligate characters, that they have exhibited Human Nature as it is. Its corruption may, indeed, be exhibited in the faulty character; but need pictures of this be held out in books? Is not vice crowned with success, triumphant, and rewarded, and perhaps set off with wit and spirit, a dangerous representation?"[4]: 149 In particular, Richardson is referring to novels of Fielding, his literary rival.[4]: 149 This note was published with the final volume of Grandison in March 1754, a few months before Fielding left for Lisbon.[4]: 149 Before Fielding died in Lisbon, he included a response to Richardson in his preface to Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon.[4]: 149

Structure

editThe epistolary form unites The History of Sir Charles Grandison with Richardson's Pamela and Clarissa, but Richardson uses the form in a different way for his final work. In Clarissa, the letters emphasise the plot's drama, especially when Lovelace alters Clarissa's letters. However, the dramatic mood is replaced in Grandison with a celebration of Grandison's moral character. In addition to this lack of dramatic emphasis, the letters of Grandison do not serve to develop character, as the moral core of each character is already complete at the outset.[5]: 236, 58

In Richardson's previous novels, the letters operated as a way to express internal feelings and describe the private lives of characters; however, the letters of Grandison serve a public function.[5]: 258 The letters are not kept to individuals, but forwarded to others to inform a larger community of the novel's action. In return, letters share the recipients' responses to the events detailed within the letters.[6] This sharing of personal feelings transforms the individual responders into a chorus that praises the actions of Grandison, Harriet, and Clementina. Furthermore, this chorus of characters emphasises the importance of the written word over the merely subjective, even saying that "Love declared on paper means far more than love declared orally".[5]: 258

Themes

edit20th-century literary critic Carol Flynn characterises Sir Charles Grandison as a "man of feeling who truly cannot be said to feel".[5]: 47 Flynn claims that Grandison is filled with sexual passions that never come to light, and he represents a perfect moral character in regards to respecting others. Unlike Richardson's previous novel Clarissa, there is an emphasis on society and how moral characteristics are viewed by the public. As such, Grandison stresses characters acting in the socially accepted ways instead of following their emotional impulses. The psychological realism of Richardson's earlier work gives way to the expression of exemplars. In essence, Grandison promises "spiritual health and happiness to all who follow the good man's exemplary pattern".[5]: 47–9 This can be taken as a sort of "political model of the wise ruler", especially with Charles's somewhat pacifist methods of achieving his goals.[7]: 111

Although Flynn believes that Grandison represents a moral character, she finds Grandison's "goodness" "repellent".[5]: 260 Richardson's other characters, like Clarissa, also exhibit high moral characters, but they are capable of changing over time. However, Grandison is never challenged in the way that Clarissa is, and he is a static, passive character. Grandison, in all situations, obeys the dictates of society and religion, fulfilling obligations rather than expressing personality. However, a character like Harriet is able to express herself fully, and it is possible that Grandison is prohibited from doing likewise because of his epistolary audience, the public.[5]: 261–2

In terms of religious responsibility, Grandison is unwilling to change his faith, and Clementina initially refuses to marry him over his religion. Grandison attempts to convince her to reconsider by claiming that "her faith would not be at risk".[8]: 70 Besides his dedication to his own religion, and his unwillingness to prevent Clementina from being dedicated to her own, he says that he is bound to helping the Porretta family. Although potentially controversial to the 18th century British public, Grandison and Clementina compromise by agreeing that their sons would be raised as Protestants and their daughters raised as Catholics.[8]: 71–2 In addition to the religious aspects, the work gives "the portrait of how a good marriage should be created and sustained".[9]: 128 To complement the role of marriage, Grandison opposes "sexual deviance" in the 18th century.[9]: 131

Critical response

editRichardson shared drafts of the novel with Dorothy Lady Bradshaigh who had contacted him anonymously when Clarissa was part published. He met her in March 1750 and she would make comments on his drafts of The History of Sir Charles Grandison and he would make amendments. Richardson wrote that his book was "owing to you … more than to any one Person besides". Richardson valued her opinions and he planned to reissue Pamela and Clarissa based on her comments. Dorothy identified herself with the character of Charlotte in The History of Sir Charles Grandison.[10]

Samuel Johnson was one of the first to respond to the published novel, but he focused primarily on the preface: "If you were to require my opinion which part [in the preface] should be changed, I should be inclined to the supression of that part which seems to disclaim the composition. What is modesty, if it deserts from truth? Of what use is the disguise by which nothing is concealed? You must forgive this, because it is meant well."[2]: 146–7 Sarah Fielding, in her introduction to The Lives of Cleopatra and Octavia, claims that people have an "insatiable Curiosity for Novels or Romances" that tell of the "rural Innocence of a Joseph Andrews, or the inimitable Virtues of Sir Charles Grandison".[11] Andrew Murphy, in the Gray's Inn Journal, emphasised the history of the production when he wrote:

Mr. Richardson, Author of the celebrated Pamela, and the justly admired Clarissa... an ingenuous Mind must be shocked to find, that Copies of very near all this Work, from which the Public may reasonable expect both Entertainment and Instruction, have been clandestinely and fraudulently obtained by a Set of Booksellers in Dublin, who have printed of the same, and advertised it in the public Papers.... I am not inclined to cast national Reflections, but I must avow, that I looked up this to be a more flagrant and atrocious Proceeding than any I have heard of for a long Time.[2]: 167

Sir Walter Scott, who favoured the bildungsroman and open plots, wrote in his "Prefatory Memoir to Richardson" to The Novels of Samuel Richardson (1824):

In his two first novels, also, he shewed much attention to the plot; and though diffuse and prolix in narration, can never be said to be rambling or desultory. No characters are introduced, but for the purpose of advancing the plot; and there are but few of those digressive dialogues and dissertations with which Sir Charles Grandison abounds. The story keeps the direct road, though it moves slowly. But in his last work, the author is much more excursive. There is indeed little in the plot to require attention; the various events, which are successively narrated, being no otherwise connected together, than as they place the character of the hero in some new and peculiar point of view. The same may be said of the numerous and long conversations upon religious and moral topics, which compose so great a part of the work, that a venerable old lady, whom we well knew, when in advanced age, she became subject to drowsy fits, chose to hear Sir Charles Grandison read to her as she sat in her elbow-chair, in preference to any other work, 'because,' said she, 'should I drop asleep in course of the reading, I am sure, when I awake, I shall have lost none of the story, but shall find the party, where I left them, conversing in the cedar-parlour.' – It is probable, after all, that the prolixity of Richardson, which, to our giddy-paced times, is the greatest fault of his writing, was not such an objective to his contemporaries.[12]

Although Scott is antipathetic towards Richardson's final novel, not everyone was of the same opinion; Jane Austen was a devotee of the novel, which was part of her mental furniture to the point where she could claim to describe "all that was ever said or done in the cedar parlour".[13] She would for example casually compare a flower in a new cap she got to the white feather described by Harriet Byron as being in hers.[14]: 220, 419 Nevertheless, throughout her life she also subjected Grandison to much affectionate, even satirical mockery[15] – adapting it into a dramatic lampoon (not published until 1980) around 1800.[16] Her juvenilia also included a heroine who guyed Harriet Byron's frequent fainting, through being "in such a hurry to have a succession of fainting fits, that she had scarcely patience enough to recover from one before she fell into another".[17] As late as 1813, she would respond to a long letter from her sister Cassandra by exclaiming "Dear me!...Like Harriet Byron I ask, what am I to do with my Gratitude".[14]: 234, 423

Later critics believed that it is possible that Richardson's work failed because the story deals with a "good man" instead of a "rake", which prompted Richardson's biographers Thomas Eaves and Ben Kimpel to claim, this "might account for the rather uneasy relationship between the story of the novel and the character of its hero, who is never credible in his double love – or in any love."[18] Flynn agrees that this possibility is an "attractive one", and conditions it to say that "it is at least certain that the deadly weighted character of Sir Charles stifles the dramatic action of the book."[5]: 48 John Mullan suggests that the problem stems from Grandison's role as a hero when he says, "his hero is able to display his virtue in action; as a consequence, Sir Charles Grandison presents its protagonist without the minutely analyzed reflexes of emotion that brought his heroines to life."[19]: 243

Some critics, such as Mark Kinkead-Weekes[20]: 291, 4 and Margaret Doody,[21] like the novel and emphasise the importance of the moral themes that Richardson takes up. In a 1987 article, Kinkead-Weekes admits that the "novel fails at the [moral] crisis" and "it must be doubtful whether it could hope for much life in the concluding volumes".[8]: 86 However, Jean Howard Hagstrum states that "Richardson's last novel is considerably better than can be easily imagined by those who have only heard about it. But admittedly it represents a falling off after Clarissa".[9]: 127 Morris Golden simply claims that the novel is a book for old men.[22]

References

edit- ^ a b Harris, Jocelyn (1972). "Introduction". Sir Charles Grandison. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-281745-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dobson, Austin (2003). Samuel Richardson. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 9781410208040. OCLC 12127114.

- ^ a b c Sale, William M (1950). "Samuel Richardson: Master Printer". Cornell Studies in English. 37. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISSN 0070-0045. OCLC 575888.

- ^ a b c d Sabor, Peter (2004). "Richardson, Henry Fielding, and Sarah Fielding". In Keymer, Thomas; Mee, Jon (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to English Literature 1740–1830. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80974-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Flynn, Carol (1982). Samuel Richardson: A Man of Letters. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-06506-3.

- ^ McKillop, A. D. (1969). "Epistolary Technique in Richardson's Novels". In Carroll, John J. (ed.). Samuel Richardson; a collection of critical essays. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0-13-791160-2.

- ^ Doody, Margaret Anne (1998). "Samuel Richardson: fiction and knowledge". In Richetti, John (ed.). Companion to the Eighteenth Century Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–119. ISBN 0-521-41908-5.

- ^ a b c Kinkead-Weekes, Mark (1987). "Crisis, Resolution, and the Family of the Heart". In Bloom, Harold (ed.). Modern Critical Views: Samuel Richardson. New York: Chelsea House. ISBN 1-55546-286-3.

- ^ a b c Hagstrum, Jean (1987). "Sir Charles Grandison: The Enlarged Family". In Bloom, Harold (ed.). Modern Critical Views: Samuel Richardson. New York: Chelsea House. ISBN 1-55546-286-3.

- ^ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (23 September 2004), "Dorothy Bradshaigh", The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39721, retrieved 6 August 2023

- ^ Fielding, Sarah (1994). Johnson, Christopher (ed.). The Lives of Cleopatra and Octavia. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-8387-5257-8.

- ^ Scott, Walter (1824). "Prefatory Memoir to Richardson". The Novels of Samuel Richardson. Vol. 1. London: Hurst, Robinson & Co. pp. xlv–vi. OCLC 230639389. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Sutherland, Kathryn (2004). "Jane Austen and the serious modern novel". In Keymer, Thomas; Mee, Jon (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to English Literature 1740–1830. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 248. ISBN 0-521-80974-6.

- ^ a b Le Faye, Deirdre, ed. (1997). Jane Austen's Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192832979.

- ^ Rawson, C. J. (1991). Introduction. Persuasion. By Austen, Jane. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. xv. ISBN 9780192827593.

- ^ Doody, Margaret Anne (September 1983). "Jane Austen's 'Sir Charles Grandison'". Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 38 (2). University of California Press: 200–224. ISSN 0029-0564. JSTOR 3044791.

- ^ Nokes, David (1997). Jane Austen: A Life. University of California Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780520216068.

- ^ Eaves, Thomas; Kimpel, Ben (1971). Samuel Richardson: a Biography. Oxford: Clarendon. p. 367. ISBN 9780198124313. OCLC 31889992.

- ^ Mullan, John (1998). "Sentimental novels". In Richetti, John (ed.). Companion to the Eighteenth Century Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 236–254. ISBN 0-521-41908-5.

- ^ Kinkead-Weekes, Mark (1973). Samuel Richardson: Dramatic Novelist. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 291, 4. ISBN 0-8014-0777-X.

- ^ Doody, Margaret Anne (1974). A Natural Passion: a Study of the Novels of Samuel Richardson. Oxford: Clarendon. p. 304. ISBN 9780198120292. OCLC 300901429.

- ^ Golden, Morris (1963). Richardson's Characters. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 181. OCLC 166541.

Add to the references: Sylvia Kasey Marks, Sir Charles Grandison: The Compleat Conduct Book. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press, 1986.

Notes

edit- In Anthony Trollope's novel The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867) Chapter XXXIX a character refers to Charles Grandison as a model of gallantry.

Further reading

edit- Townsend, Alex, Autonomous Voices: An Exploration of Polyphony in the Novels of Samuel Richardson, 2003, Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt/M., New York, Wien, 2003, ISBN 978-3-906769-80-6 / US-ISBN 978-0-8204-5917-2

External links

edit- The History of Sir Charles Grandison, at The University of Adelaide eBooks@Adelaide

- Sir Charles Grandison, Volume 4 (of 7) at Gutenberg

- Sir Charles Grandison, Volume 1 through 7 at HathiTrust

- Entry in the Literary Encyclopedia