Sir John Soane's Museum is a house museum, located next to Lincoln's Inn Fields in Holborn, London, which was formerly the home of neo-classical architect John Soane. It holds many drawings and architectural models of Soane's projects and a large collection of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and antiquities that he acquired over many years. The museum was established during Soane's own lifetime by a private Act of Parliament in 1833, which took effect on his death in 1837.[3] Soane engaged in this lengthy parliamentary campaign in order to disinherit his son, whom he disliked intensely. The act stipulated that on Soane's death, his house and collections would pass into the care of a board of trustees acting on behalf of the nation, and that they would be preserved as nearly as possible exactly in the state they were at his death. The museum's trustees remained completely independent, relying only on Soane's original endowment, until 1947. Since then, the museum has received an annual Grant-in-Aid from the British Government via the Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

| |

| Established | 1837 |

|---|---|

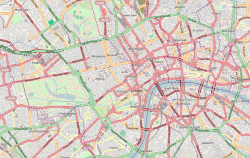

| Location | Lincoln's Inn Fields London, WC2 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°31′01″N 0°07′03″W / 51.516998°N 0.117402°W |

| Collection size | 45,000 objects, approx. 30,000 architectural drawings[1] |

| Visitors | 107,903 (2011–2012)[2] |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

From 1988 onwards, a programme of restoration was carried out, with spaces such as the drawing rooms, picture room, study and dressing room, picture room recess and others, restored to their original colour schemes and in most cases having their original sequences of objects reinstated. Soane's three courtyards were also restored with his pasticcio (a column of architectural fragments) being reinstated in the monument court at the heart of the museum. In 1997, the trustees purchased the main house at No. 14 with the help of the Heritage Lottery Fund. The house was restored and has enabled the museum to expand its educational activities, to re-locate its research library, and create a Robert Adam Study Centre where Soane's collection of 9,000 Robert Adam drawings is housed.

Some of Soane's paintings include works by Canaletto, Hogarth, three works by his friend J. M. W. Turner, Thomas Lawrence, Antoine Watteau, Joshua Reynolds, Augustus Wall Callcott, Henry Fuseli, William Hamilton and 15 drawings by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, many of which are framed and displayed in the museum. There are over 30,000 architectural drawings in the collection, along with various Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, including the Sarcophagus of Seti I. Owing to the narrow passages in the house, all decked with Soane's extensive collections, only 90 visitors are allowed in the museum at any given time, and a formation of queue outside for entry is not unusual. Labels are few and lighting is discreet; there is no information desk or café. In the year ending March 2019, the museum received 131,459 visitors.[4]

History

editHouses

editSoane demolished and rebuilt three houses in succession on the north side of Lincoln's Inn Fields. He began with No. 12 (between 1792 and 1794), externally a plain brick house. After becoming Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy in 1806, Soane purchased No. 13, the house next door, today the museum, and rebuilt it in two phases in 1808–09 and 1812.

In 1808–09, Soane constructed his drawing office and "museum" on the site of the former stable block at the back, using primarily top lighting. In 1812, he rebuilt the front part of the site, adding a projecting Portland stone façade to the basement, ground and first floor levels and the centre bay of the second floor. Originally, this formed three open loggias, but Soane glazed the arches during his lifetime. Once he had moved into No. 13, Soane rented out his former home at No. 12 (on his death it was left to the nation along with No. 13, the intention being that the rental income would fund the running of the museum).

After completing No.13, Soane set about treating the building as an architectural laboratory, continually remodelling the interiors. In 1823, when he was over 70, he purchased a third house, No. 14, which he rebuilt in 1823–24. This project allowed him to construct a picture gallery, linked to No.13, on the former stable block of No. 14. The front main part of this third house was treated as a separate dwelling and let as an investment; it was not internally connected to the other buildings. When he died, No. 14 was bequeathed to his family and passed out of the museum's ownership.

Museum

edit| Sir John Soane's Museum Act 1833 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| Citation | 3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 4 |

The museum was established during Soane's own lifetime by a private Act of Parliament (3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 4) in 1833, which took effect on Soane's death in 1837. The act required that No. 13 be maintained "as nearly as possible" as it was left at the time of Soane's death, and that has largely been done. The act was necessary because Sir John had a living direct male heir, his son George, with whom he had had a "lifelong feud" due to George's debts, refusal to engage in a trade, and his marriage, of which Sir John disapproved. He also wrote an "anonymous, defamatory piece for the Sunday papers about Sir John, calling him a cheat, a charlatan and a copyist".[5] Since under contemporary inheritance law George would have been able to lay claim to Sir John's property on his death, Sir John engaged in a lengthy parliamentary campaign to disinherit his son via a private Act, setting out to "reverse the fundamental laws of hereditary succession"[6] according to some. The Soane Museum Act was passed in April 1833 and stipulated that on Soane's death his house and collections would pass into the care of a board of trustees, on behalf of the nation, and that they should be preserved as nearly as possible exactly as they were left at his death.[7]

Towards the end of the 19th century (1889–90) a break-through was made to re-connect the rear rooms of No. 12 (north of the courtyard) through to the museum in No. 13 and since 1969 No. 12 has been run by the trustees as part of the museum, housing the research library (until 2009), offices and, since 1995, the Eva Jiřičná-designed 'Soane Gallery' for temporary exhibitions (until Summer 2011). The museum's trustees remained completely independent, relying only on Soane's original endowment, until 1947. Since that date the museum has received an annual Grant-in-Aid from the British Government (this now comes via the Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport).

Restoration projects

editThe Soane Museum is now a national centre for the study of architecture. From 1988 to 2005, a programme of restoration within the museum was carried out under Peter Thornton and then Margaret Richardson with spaces such as the drawing rooms, picture room, study and dressing room, picture room recess and others being put back to their original colour schemes and in most cases having their original sequences of objects reinstated; Soane's three courtyards were also restored with his pasticcio (a column of architectural fragments) being reinstated in the monument court at the heart of the museum. (Much of the cost of the work was financed by the Sir John Soane's Museum Foundation, in New York.)[8]

In 1997, the trustees purchased the main house at No. 14 with the help of the Heritage Lottery Fund.[7] The house was restored (2006–09) and has enabled the museum to expand its educational activities, to re-locate its Research Library into that house, and to create a Robert Adam Study Centre where Soane's collection of 9,000 Robert Adam drawings is housed in purpose-designed new cabinets by Senior and Carmichael.

Opening up the Soane project, 2011–2016

editThe acquisition of No. 14 enabled the museum under its new director Tim Knox to complete the restoration of the museum's historic spaces,[7][9] for about £7 million, funded by the Monument Trust, the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Soane Foundation in New York, and other private trusts.[10] The museum's architects are Julian Harrap Architects.

Phase 1 began in March 2011 and was completed in 2013.[11] It included the re-configuration of No. 12, moving the temporary exhibition gallery up to the first floor (with new showcases etc. designed by Caruso St John), and new reception facilities and a shop on the ground floor. It also included new conservation studios, named the John and Cynthia Fry Gunn Conservation Centre, and the installation of lifts to provide disabled access for the first time.

Phase 2 saw the restoration of Soane's private apartments on the second floor (bedroom, book room, model room, oratory and Mrs Soane's morning room)[9][12] and opened to public tours in summer 2015.[9][13] Lost rooms recreated include Soane's own bedroom and bathroom, which he showed to the public in his lifetime.[12][14]

Phase 3 provided a new Study Room at the back of No. 12 for the public to learn more about Soane, and restoration of Soane's ground-floor Ante Room with almost 200 works of art and the catacombs beneath it.[15] The final Phase 3 of the programme was completed in summer 2016.[16]

Architecture

editThe most famous spaces in the house are those at the rear of the museum – the dome area, colonnade and museum corridor. These are mostly toplit and provide some idea in miniature form of the ingenious lighting contrived by Soane for the toplit banking halls at the Bank of England. The ingeniously designed Picture Gallery has walls composed of large 'moveable planes' (like large cupboard doors) that allow it to house three times as many items as a space of this size could normally accommodate (the original hang in this room was reinstated in January 2011). When visiting, it is necessary to request the planes to be opened and wait for a group to gather before this is done.

The more domestic rooms of No. 13 are at the front of the house, many of them highly unusual, but often in subtle ways. The domed ceiling of the Breakfast Room, inset with convex mirrors, has influenced architects from around the world. The Library-Dining Room reflects the influence of Etruscan tombs and perhaps even gothic design in its repertoire of small pendants like those in fan vaulting. It is decorated in a rich 'Pompeian' red. The Study contains a collection of Roman architectural fragments and the two external courtyards, the Monument Court and Monk's Yard contain an array of architectural fragments, Classical in the Monument Court with its central column or 'pasticcio' representing Architecture and Gothic in the Monk's Yard, filled with medieval stonework from the Palace of Westminster.

Collections

editAntiquities, medieval and non-western objects

editAs his practice prospered, Soane was able to collect objects worthy of the British Museum, including the Sarcophagus of Seti I, covered in Egyptian hieroglyphs, discovered by Giovanni Battista Belzoni, bought on 12 May 1824 for £2000 (equivalent to £222,000 in 2023)—Soane's most expensive art work.[17]

After the Seti sarcophagus arrived at his house in March 1825, Soane held a three-day party, to which 890 people were invited, the basement where the sarcophagus was housed was lit by over one hundred lamps and candelabra, refreshments were laid on and the exterior of the house was hung with lamps.[18] Among the guests were the then Prime Minister Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool and his wife, Robert Peel, Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, J.M.W. Turner, Sir Thomas Lawrence, Charles Long, 1st Baron Farnborough, Benjamin Haydon as well as many foreign dignitaries.[19]

Other antiquities include: Greek and Roman bronzes, including ones from Pompeii, cinerary urns, fragments of Roman mosaics, Greek vases many displayed above the bookcases in the library, Greek and Roman busts, heads from statues and fragments of sculpture and architectural decoration, examples of Roman glass.[20]

Medieval objects include: architectural fragments, mainly from the Old Palace of Westminster (acquired after the 1834 fire), tiles and stained glass.[20] Soane acquired 44 examples of 18th-century Chinese ceramics as well as 12 examples of Peruvian pottery.[21] Soane also purchased four ivory chairs and a table, believed to be made in Murshidabad for Tipu Sultan's palace at Srirangapatna.[22]

Sculpture

editFrancis Leggatt Chantrey carved a white marble bust of Soane that is still in the museum, in the 'Dome' overlooking the Seti sarcophagus.[23] Soane also acquired Sir Richard Westmacott's plaster model for Nymph unclasping her Zone, displayed at the back of the recess in the Picture Room.[24] Other acquisitions include: the plaster model of John Flaxman's memorial sculpture of William Pitt the Younger.[25] The model of Thomas Banks's monument to Penelope Boothby.[26]

Of ancient sculptures a miniature copy of the famous sculpture of Diana of Ephesus is one of the most important in the collection.[27] After the death of his teacher Henry Holland, Soane bought part of his collection of ancient marble fragments of architectural decoration, these were purchased by Charles Heathcote Tatham for Holland in Rome in 1794–96.[28]

Plastercasts of famous antique sculptures include: Aphrodite of Cnidus,[25] Hercules Hesperides[29] & Apollo Belvedere.[30] Soane also acquired a plastercast of the Sulis Minerva sculpture found in Bath.[31]

Paintings and drawings

editSoane's paintings include: works by Canaletto entitled View of the Riva degli Schiavoni painted (1736) purchased in 1806 from William Thomas Beckford for 150 Guineas[32] plus three other works by the artist,[33] and paintings by Hogarth: the eight canvases of the A Rake's Progress, purchased from the collection of William Thomas Beckford, at auction for 570 Guineas in 1801,[34] the other Hogarth paintings Soane purchased were the four canvases of the Humours of an Election bought at auction at Christie's from David Garrick's widow for £1,732, 10s in June 1823.[35] Soane acquired three works by his friend J. M. W. Turner: the oil paintings Admiral Van Tromp's Barge entering the Texel and St Hugues Denouncing Vegeance on the Shepherd of Cormayer Val D'Aoust and the watercolour Kirkstall Abbey. Thomas Lawrence painted a three quarter length portrait of Soane, it is hung over the Dining Room fireplace in the museum.[36] Soane also has a painting by Antoine Watteau, a fête champêtre.[24] Soane owned one oil painting by Joshua Reynolds, entitled Love and Beauty, which hangs in the dining room over the sideboard.[37] Soane commissioned an oil painting from Augustus Wall Callcott c.1830, entitled The Passage Point -Italian Composition.[38] Other paintings include The Count of Revenna by Henry Fuseli, and The Landing of Richard II at Milford Haven by William Hamilton.[39] Soane acquired 15 drawings by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, many of which are framed and displayed in the museum.[21] Soane's friend John Flaxman, sketched Soane's wife, this is framed and displayed in the museum.[40] The collection also includes twenty-two works in gouache and bodycolour by Charles-Louis Clérisseau.[citation needed]

-

Canaletto – View of Venice, The Riva Degli Schiavoni, looking West, c. 1736

-

Canaletto – A View of the Rialto

Architectural drawings and architectural models

editThere are over 30,000 architectural drawings in the collection. Of Soane's drawings of his own designs (many are by his assistants and pupils, most notably Joseph Gandy), covering his entire career, most are bound in 37 volumes, 97 are framed on the museum walls, and the rest are 601 covering the Bank of England, 6,266 of his other works, and 1,080 prepared for the Royal Academy lectures.[41]

In 1817 George Dance the Younger gave Soane a gift of a book containing architectural drawings by Christopher Wren, including Hampton Court Palace & Royal Naval Hospital.[42] A major coup for Soane's collection was the purchase of the 57 volumes of 8,856 drawings by Robert Adam and James Adam in 1821 for £200.[43] Another important architectural book was John Thorpe's book of architecture, purchased at an auction held at Christie's on 3 April 1810 and costing Soane 27+1⁄2 Guineas;[44] the book contains nearly 300 plans and elevations of Elizabethan architecture and Jacobean architecture, mainly large mansions. George Dance the Younger died in 1825, and in 1836 Soane purchased both George Dance the Elder's 293 and George Dance the Younger's 1,303 surviving drawings from his son, which were housed in the museum in a specially designed cabinet;[45] Sir William Chambers 789 drawings; James Playfair 286 drawings; other architects and artists with drawings in the collection include: Matthew Brettingham, Thomas Sandby, Humphry Repton, Joseph Nollekens, Peter Scheemakers, John Michael Rysbrack, and others, in total 1,635 drawings.[41] There are a large number of Italian drawings, including an early 16th-century bound volume by Nicolette da Modena; the Codex Coner early 16th century of Roman buildings; 213 mid-16th century drawings by Giorgio Vasari; 3 volumes of 16th to 17th-century drawings by Giovanni Battista Montano; 17th-century drawings by Giovanni Battista Gisleni; two volumes of 18th-century drawings by Carlo Fontana; Drawings of Paestum dated 1768 by Thomas Major; Margaret Chinnery's volume of miscellaneous drawings; plus six other volumes of various drawings.[46]

The 252 architectural models in the collection are: 118 of Soane's own buildings including 44 of the Bank of England, covering details, façades, rooms as well as complete buildings,[21] models of ancient Roman and Greek buildings, 20 made from plaster and 14 of cork.[21] There are in addition 100 models of architectural details and ornaments.[21] The 20 plaster models are the work of Jean-Pierre Fouquet of Paris and were acquired by Soane in 1834 for £100,[47] these include: Erechtheion, Tower of the Winds, Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, Pantheon, Rome, Temple of Vesta, Tivoli, Temple of Antoninus and Faustina and the Temple of Portunus, the buildings are depicted as reconstructions not in their current ruined state.

Management

editAttendance

editTo this day only 90 visitors are allowed at a time, which often means a queue outside. Labels are few and lighting is discreet; there is no information desk or café. In 2010, the museum attracted 110,000 visitors.[48]

Staff

editSoane's will provided for there to be a curator, and an inspectress (the post was created for Soane's housekeeper and close family friend Mrs Sarah Conduitt). The architectural historian Sir John Summerson was curator of the museum from 1945 to 1984. He was assisted by Dorothy Stroud, who served as inspectress from 1945 to 1985.

Summerson was succeeded by Peter Thornton who moved from the Victoria and Albert Museum to take up the post. Thornton retired in 1995, and was followed by Margaret Richardson, the first woman to hold the title of curator. She had succeeded Stroud as inspectress in 1985, and served as curator until 2005, with Helen Dorey as inspectress). From 2005 the director of the museum was Tim Knox, previously head curator of the National Trust, under whose leadership the museum has embarked on the ambitious 'Opening up the Soane' project combining the restoration of Nos. 12 and 13, including a number of lost historic features, with improved visitor and conservation facilities. The 'Opening up the Soane' project also includes a programme of audience development, a new website and on-line catalogues of the collections. In 2013, the Victoria and Albert Museum's design and architecture curator Abraham Thomas was named director of the Sir John Soane's Museum.[49] Thomas was succeeded in the post in 2016 by Bruce Boucher, former director of the Fralin Museum of Art.[50] It was announced on 4 August 2023 that Will Gompertz will take over as Director from January 2024.[51]

See also

edit- Soane's country retreat Pitzhanger Manor, in Ealing

- The Dulwich Picture Gallery designed by Soane in 1811 is the archetype for modern art galleries from the Sainsbury Wing at London's National Gallery to the new Getty Center in California.

- With its eclectic collection idiosyncratically displayed in a domestic town house, the Soane museum shares many qualities with the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

- Sir John Soane should not be confused with Sir Hans Sloane, whose collections formed the foundation of the British Museum, the British Library and Natural History Museum.

- James William Wild curator in the 1880s.

- Sir John Soane's mausoleum is located at the St. Pancras Old Church.

- List of single-artist museums

Notes

edit- ^ "Collections". soane.org. 14 July 2015.

- ^ "Reports and accounts for the year ended 31 March 2012" (PDF). Soane Museum. 17 July 2012. p. 30. Retrieved 2 June 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Our History". Sir John Soane's Museum. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ "Sir John Soane's Museum Registered Charity No. 313609 THE ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1 APRIL 2018 TO 31 MARCH 2019" (PDF). soane.org. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Biographies: Sir John Soane (1753–1837)". Berkshire History. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "SIR JOHN SOANE'S MUSEUM". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 1 April 1833. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Soane Museum.org: "What is the 'Opening up the Soane' Project?" Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine . accessed 9 September 2015.

- ^ Paula Deitz (13 April 1995), Sir John Soane's New Tricks The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Architectural Record, "Sir John Soane at Home," September 2015, pgs. 39-40.

- ^ "Soane Museum.org: Donors to the OUTS project". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015.

- ^ "Soane Museum.org: OUTS Phase I, No.12 Lincoln's Inn Fields". Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Soane Museum.org: OUTS Phase II, Soane's Private Apartments". Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ Soane Museum.org: Tours Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Private Apartments and Model Room Toura . accessed 9 September 2015.

- ^ The Guardian: "Sir John Soane museum's lost gallery is flushed out", Maev Kennedy (14 February 2011).

- ^ "Soane Museum.org: OUTS Phase III, The Ante-Room, catacombs, Curved Link Passage and the Foyle Project Space". Archived from the original on 27 December 2014.

- ^ Soane Museum.org: Accessibility ("Please note" section) accessed 9 September 2015.

- ^ Darley 1999, p. 274

- ^ Darley 1999, p. 275

- ^ Darley 1999, p. 276

- ^ a b Soane Museum 1991, p. 84

- ^ a b c d e Soane Museum 1991, p. 85

- ^ Knox 2009, p. 122

- ^ Stroud 1984, p. 113

- ^ a b Knox 2009, p. 93

- ^ a b Knox 2009, p. 70

- ^ Knox 2009, p. 83

- ^ Knox 2009, p. 66

- ^ Knox 2009, p. 60

- ^ Knox 2009, p. 78

- ^ Knox 2009, p. 120

- ^ Knox 2009, p. 73

- ^ Stroud 1984, p. 60

- ^ Stroud 1984, p. 32

- ^ Darley 1999, p. 148

- ^ Darley 1999, p. 271

- ^ Stroud 1984, p. 109

- ^ Knox 2009, p. 57

- ^ Stroud 1984, p. 86

- ^ Sir John Soane's Museum (2018). Sir John Soane's Museum: A Complete Description. Sir John Soane's Museum. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-9932041-6-6.

- ^ Stroud 1984, p. 101

- ^ a b Soane Museum 1991, p. 86

- ^ Darley 1999, p. 253

- ^ Tait 2008, p. 11

- ^ Summerson 1966, p. 15

- ^ Lever 2003, p. 10

- ^ Soane Museum 1991, pp. 85–86

- ^ Soane Museum 1991, p. 65

- ^ Richard Dorment (1 March 2011), Sir John Soane's Museum: the museum that time forgot The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Pac Pobric (24 July 2013), Design curator to lead Soane's Museum Archived 26 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

- ^ "New Soane Museum Director Appointed". Sir John Soane's Museum. 16 February 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ "Will Gompertz to take over as Director of the Sir John Soane's Museum". ianVisits. 4 August 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

Bibliography

edit- Darley, Gillian (1999). John Soane: An Accidental Romantic. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08165-7.

- A New Description of Sir John Soane's Museum: 9th Revised Edition. The Trustees of the Sir John Soane's Museum. 1991.

- Knox, Tim (2009). Sir John Soane's Museum London. Merrell. ISBN 978-1-85894-475-3.

- Lever, Jill (2003). Catalogue of the Drawings of George Dance the Younger (1741–1825) and of George Dance the Elder (1695–1768) from the Collection of Sir John Soane's Museum. Azimuth Editions. ISBN 978-1-898592-25-9.

- Stroud, Dorothy (1984). Sir John Soane Architect. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-13050-4.

- Summerson, John (1966). "The Book of John Thorpe in Sir John Soane's Museum". The Fortieth Volume of the Walpole Society 1964–1965. The Walpole Society.

- Tait, A. A. (2008). The Adam Brothers in Rome: Drawings from the Grand Tour. Scala Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85759-574-1.

Further reading

edit- Reynolds, Nicole (2010). "Sir John Soane's House-Museum and Romantic Nostalgia". Building Romanticism: Literature and Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Britain. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11731-4.

- Stourton, James (2012). Great Houses of London. Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3366-9.

- Waterfield, Giles, ed. (1996). Soane and Death. Dulwich Picture Gallery. ISBN 978-1-898519-08-9.