In Greek and Roman mythology, Sirius (/ˈsɪrɪəs/, SEE-ree-əss; Ancient Greek: Σείριος, romanized: Seírios, lit. 'scorching' pronounced [sěːrios]) is the god and personification of the star Sirius, also known as the Dog Star, the brightest star in the night sky and the most prominent star in the constellation of Canis Major (or the Greater Dog).[1] In ancient Greek and Roman texts, Sirius is portrayed as the scorching bringer of the summer heatwaves, the bright star who intensifies the Sun's own heat.

| Sirius | |

|---|---|

God of the star Sirius | |

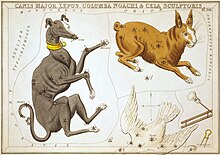

Canis Major and Lepus with Sirius as the dog's snout, as depicted in Urania's Mirror, a set of constellation cards c. 1825. | |

| Greek | Σείριος |

| Abode | Sky |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | |

| Siblings | the Stars |

| Consort | Opora |

Etymology

editThe ancient Greek word and proper noun Σείριος has been connected to the verb σείω (seíō), meaning to 'sparkle, to gleam' and has thus an Indo-European etymology; Furnée on the other hand compared it to the word τίριος (tírios), the Cretan word for summer, which, if correct, would mean that the word is pre-Greek instead.[2] From this name an ancient phrase was derived, σείριον πάθος (literally "sirian passion", meaning burning passion).[3]

Description

editSirius's divine parentage is not made entirely clear in ancient texts; in the Theogony the poet Hesiod names Eos (the dawn goddess) and her husband Astraeus (a star god) as the parents of all stars, although this usually referred to the 'wandering stars', that is the five planets.[4]

Sirius is first mentioned by name in Hesiod's Works and Days,[5][6] although he is also strongly alluded to in Homer's Iliad, with his brilliance used as a metaphor for the shiny bronze armors of the soldiers, and in another point he is presented as an ominous death star foreshadowing the fate of the doomed Hector in his fight against Achilles.[7] Apollonius of Rhodes calls him "brilliant and beautiful but full of menace for the flocks,"[8] and both Aratus and Quintus of Smyrna speak of his rise in conjunction to that of the Sun (the god Helios).[9] The Roman poet Statius says:

Tempus erat, caeli cum |

Twas the season when the vault |

In addition to that, "Sirius" was sometimes used as an epithet of Helios himself due to the Sun's great heat and warmth.[11][12]

Sirius and his appearance in the sky in July and August was associated with heat, fire and fever by the ancient Greeks from early on,[13] as was his association with dogs; as the chief star in the constellation Canis Major, he was referred to as 'the Dog', which also referred to the entire constellation.[14] The arrival of Sirius in the sky was seen as the cause behind the hot, dry days of summer; dogs were thought to be the most affected by Sirius's heat, causing them rapid panting and aggressive behaviour towards humans, who were in danger of contacting rabies from their bites.[15]

Sirius, a luminous star brighter than the Sun, is very often described as red in some ancient Greek and Roman texts, put in the same category as the red-shining Mars and Antares, although in reality it is a white-blue star.[16]

Mythology

editRomance with Opora

editIn a lesser known narrative, back when the stars walked the earth, Sirius was sent on a mission on land. There he met and fell madly in love with Opora, the goddess of fruit as well as the transition between summer and autumn. He was however unable to be with her, so in anger he began to burn even hotter.[17] The mortals started to suffer due to the immense heat, and pleaded to the gods.[18] Then the god of the north wind, Boreas, ordered his sons to bring Opora to Sirius, while he himself cooled off the earth with blasts of cold, freezing wind.[19] Sirius then went on to glow and burn hot every summer thereafter during harvest time in commemoration of this event and his great love, explaining the heat of the so-called dog days of summer, which was attributed to this star in antiquity.[20]

The story is generally believed to have originated from a lost play entitled Opora, by the Athenian playwright of Middle Comedy Amphis, and a work of the same name by Amphis's contemporary Alexis.[19] It also parallels the tale of young Phaethon, the son of the sun-god Helios who drove his father's sun chariot for a day and ended up burning the earth with it, prompting the entire nature to beg Zeus for salvation.[19] In Euripides's version of the story, Helios accompanies Phaethon in his journey riding on a steed named Sirius.[12]

Orion

editAfter the mortal hunter Orion was killed by the scorpion the earth-goddess Gaia sent to punish him, he was transported by the gods (usually either Artemis or Zeus) in the stars as the homonymous constellation, where he was ever accompanied by his faithful dog, who was represented by Sirius (and Canis Major) in their new celestial lives.[21][22] This belief seems to originate from the fact that the Dog forms a sky-picture with Orion, as the two hunt Lepus (the Hare) or the Teumessian fox through the sky.[20]

Maera

editSirius is also identified with Maera (Ancient Greek: Μαῖρα, romanized: Maira, lit. 'sparkler'), which was another name for the dog star in antiquity.[23] In mythology Maera was the hound of Icarius, an old Athenian an who was taught the art of wine-making by Dionysus. When Icarius shared the wine with the other Athenians he was accused of poisoning them (due to the wine's intoxicating properties which made them pass out) and he was thus killed in vengeance; his daughter Erigone, after being led to his corpse by Maera, took her own life by hanging.[24] Dionysus then transferred all three in the sky, with Maera becoming the star Canicula, which was the Romans' name for Sirius,[25][26] although Hyginus himself claimed that the Greeks used Procyon for Canicula.[27]

Other works

editIn second-century author Lucian's satire work A True Story, the people of Sirius, here presented as an inhabited world, send an army of Cynobalani (dog-faced men mounting gigantic winged acorns) to assist the Sun citizens in their war against the inhabitants of the Moon.[28] Sirius, associated with heat, is an appropriate ally for the kingdom of the Sun.[29]

Cult

editIn antiquity, Sirius might have been venerated on the island of Kea with summer sacrifices to his honour during the Hellenistic period,[15] though certain doubts have been cast on whether such cult did exist indeed; at any point, that cult surely did not predate the third century BC.[23] Keans would observe Sirius's rising from a hilltop; if the star rose clear and brilliant it was a good sign of health, but if it appeared faint or misty it was seen as ominous. Sirius was also represented on coinage from Kea.[15]

See also

edit- Orithyia of Athens

- Hou Yi and the Ten Suns

- Pyroeis, the star of Mars

References

edit- ^ Hinckley, Richard Allen (1899). Star-names and Their Meanings. New York: G. E. Stechert. pp. 117–129.

- ^ Beekes 2010, p. 1317.

- ^ Liddell & Scott 1940, s.v. σείριος.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 378

- ^ Hesiod, Works and Days 417

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 15.

- ^ Holberg 2007, pp. 17-18.

- ^ Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 3.958 ff

- ^ Aratus, Phaenomena 328; Quintus of Smyrna, Fall of Troy 8.30

- ^ Statius, Silvae 3.1.5. Transkation by John Henry Mozley.

- ^ Archilochus 61.3; Scholia on Euripides' Hecuba 1103

- ^ a b Diggle 1970, p. 138.

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Holberg 2007, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Holberg 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Kelley, David H.; Milone, Eugene F. (16 February 2011). Exploring Ancient Skies: A Survey of Ancient and Cultural Astronomy. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-1-4419-7623-9.

- ^ Schol. latinus Arati p. 78

- ^ Käppel, Lutz (2006). "Opora". In Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). Brill's New Pauly. Translated by Christine F. Salazar. Kiel: Brill Reference Online. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e832290. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c Arnott, William Geoffrey (1955). "A Note on Alexis' Opora". Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 98 (4): 312–15. JSTOR 41243800. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ a b Wright, M. Rosemary (September 2012). "A Dictionary of Classical Mythology: III The Constellations of the Southern Sky". mythandreligion.upatras.gr. University of Patras. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 26-29

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 561.

- ^ a b Reitz & Finkmann 2019, p. 1893.

- ^ Doniger 1999, s.v. Erigone.

- ^ "canicular". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ Pavlock 2009, p. 57.

- ^ Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.4.4

- ^ Lucian, A True Story 1.15

- ^ Georgiadou & Larmour 1998, p. 110.

Bibliography

edit- Apollonius Rhodius, The Argonautica translated by E. V. Rieu, Penguin Classics, April 1959. ISBN 978-0140440850.

- Aratus Solensis, Phaenomena translated by G. R. Mair. Loeb Classical Library Volume 129. London: William Heinemann, 1921. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (2010). Lucien van Beek (ed.). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series. Vol. ΙΙ. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill Publications. ISBN 978-90-04-17419-1.

- Diggle, James (1970). Euripides: Phaethon. Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries, Number 12. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521604246.

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999). "Erigone". Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions. Merriam-Webster. ISBN 0-87779-044-2.

- Gaius Julius Hyginus, De Astronomica from The Myths of Hyginus translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Georgiadou, Aristoula; Larmour, David H. J. (1998), Lucian's Science Fiction Novel True Histories: Interpretation and Commentary, Supplements to Mnemosyne, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004351509, ISBN 90-04-10667-7

- Hard, Robin (2004). The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology". Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415186360.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Works and Days, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Holberg, J. B. (2007). Sirius: Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing. ISBN 978-0-387-48941-4.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at perseus.tufts Library.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Online version at Perseus.tufts project.

- Lucian (1962), "A True Story", in Casson, Lionel (ed.), Selected Satires of Lucian, New York: W. W. Norton & Co., pp. 13–57, doi:10.4324/9781315129105-4, ISBN 0-393-00443-0

- Pavlock, Barbara (May 21, 2009). The Image of the Poet in Ovid's Metamorphoses. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-23140-8.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy, translated by Arthur S. Way, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1913. Internet Archive.

- Reitz, Christiane; Finkmann, Simone (December 16, 2019). Structures of Epic Poetry. Vol. I: Foundations, II: Classification and Genre. de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-049200-2.

- Statius, Silvae, translated by John Henry Mozley, London, W. Heinemann, Ltd.; New York, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1928. Available on Internet Archive.