Skull symbolism is the attachment of symbolic meaning to the human skull. The most common symbolic use of the skull is as a representation of death.

Humans can often recognize the buried fragments of an only partially revealed cranium even when other bones may look like shards of stone. The human brain has a specific region for recognizing faces,[1] and is so attuned to finding them that it can see faces in a few dots and lines or punctuation marks; the human brain cannot separate the image of the human skull from the familiar human face. Because of this, both the death and the now-past life of the skull are symbolized.

Hindu temples and depiction of some Hindu deities have displayed association with skulls.

Moreover, a human skull with its large eye sockets displays a degree of neoteny, which humans often find visually appealing—yet a skull is also obviously dead, and to some can even seem to look sad due to the downward facing slope on the ends of the eye sockets. A skull with the lower jaw intact may also appear to be grinning or laughing due to the exposed teeth. As such, human skulls often have a greater visual appeal than the other bones of the human skeleton, and can fascinate even as they repel. Societies predominantly associate skulls with death and evil.

Unicode reserves character U+1F480 (💀) for a human skull pictogram.

Examples

editThroughout the centuries skulls symbolized either warnings of various threats or as reminder of the vanity of earthly pleasures in contrast with our own mortality. Nevertheless, the skull seems to be omnipresent in the first decade of the twenty-first century, appearing on jewelry, bags, clothing and in the shape of various decorative items. However, the increasing use of the skull as a visual symbol in popular culture reduces its original meaning as well as its traditional connotation.[2][3]

Literature

editOne of the best-known examples of skull symbolism occurs in Shakespeare's Hamlet, where the title character recognizes the skull of an old friend: "Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio; a fellow of infinite jest..." Hamlet is inspired to utter a bitter soliloquy of despair and rough ironic humor.

Compare Hamlet's words "Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft" to Talmudic sources: "...Rabi Ishmael [the High Priest]... put [the severed head of a martyr] in his lap... and cried: oh sacred mouth!...who buried you in ashes...!". The skull was a symbol of melancholy for Shakespeare's contemporaries.[4]

An old Yoruba folktale tells of a man who encountered a skull mounted on a post by the wayside. To his astonishment, the skull spoke. The man asked the skull why it was mounted there. The skull said that it was mounted there for talking. The man then went to the king, and told the king of the marvel he had found, a talking skull. The king and the man returned to the place where the skull was mounted; the skull remained silent. The king then commanded that the man be beheaded, and ordered that his head be mounted in place of the skull.[5]

The skull speaks in the catacombs of the Capuchin brothers beneath the church of Santa Maria della Concezione in Rome,[6] where disassembled bones and teeth and skulls of the departed Capuchins have been rearranged to form a rich Baroque architecture of the human condition, in a series of anterooms and subterranean chapels with the inscription, set in bones:

- Noi eravamo quello che voi siete, e quello che noi siamo voi sarete.

- "We were what you are; and what we are, you will be."

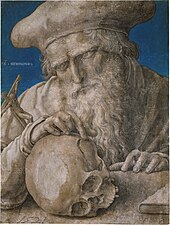

Art

editThe Serpent crawling through the eyes of a skull is a familiar image that survives in contemporary Goth subculture. The serpent is a chthonic god of knowledge and of immortality, because he sloughs off his skin. The serpent guards the Tree in the Greek Garden of the Hesperides and, later, a Tree in the Garden of Eden. The serpent in the skull is always making its way through the socket that was the eye: knowledge persists beyond death, the emblem says, and the serpent has the secret.

The late medieval and Early Renaissance Northern and Italian painters place the skull where it lies at the foot of the Cross at Golgotha (Aramaic for the place of the skull). But for them it has become quite specifically the skull of Adam.

In Elizabethan England, the Death's-Head Skull, usually a depiction without the lower jawbone, was emblematic of bawds, rakes, sexual adventurers and prostitutes; the term Death's-Head was actually parlance for these rakes, and most of them wore half-skull rings to advertise their station, either professionally or otherwise. The original Rings were wide silver objects, with a half-skull decoration not much wider than the rest of the band; This allowed it to be rotated around the finger to hide the skull in polite company, and to reposition it in the presence of likely conquests.[citation needed]

Venetian painters of the 16th century elaborated moral allegories for their patrons, and memento mori was a common theme. The theme carried by an inscription on a rustic tomb, "Et in Arcadia ego"—"I too [am] in Arcadia", if it is Death that is speaking—is made famous by two paintings by Nicolas Poussin, but the motto made its pictorial debut in Guercino's version, 1618–22 (in the Galleria Barberini, Rome): in it, two awestruck young shepherds come upon an inscribed plinth, in which the inscription ET IN ARCADIA EGO gains force from the prominent presence of a wormy skull in the foreground.

In C. Allan Gilbert's much-reproduced lithograph of a lovely Gibson Girl seated at her fashionable vanity table, an observer can witness its transformation into an alternate image. A ghostly echo of the worldly Magdalene's repentance motif lurks behind this turn-of-the-20th century icon. The skull becomes an icon itself when its painted representation becomes a substitute for the real thing. Simon Schama chronicled the ambivalence of the Dutch to their own worldly success during the Dutch Golden Age of the first half of the 17th century in The Embarrassment of Riches.

The possibly frivolous and merely decorative nature of the still life genre was avoided by Pieter Claesz in his Vanitas: Skull, opened case-watch, overturned emptied wineglasses, snuffed candle, book: "Lo, the wine of life runs out, the spirit is snuffed, oh Man, for all your learning, time yet runs on: Vanity!" The visual cues of the hurry and violence of life are contrasted with eternity in this somber, still and utterly silent painting.

The skull speaks. It says "Et in Arcadia ego" or simply "Vanitas." In a first-century mosaic tabletop from a Pompeiian triclinium (now in Naples), the skull is crowned with a carpenter's square and plumb-bob, which dangles before its empty eyesockets (Death as the great leveler), while below is an image of the ephemeral and changeable nature of life: a butterfly atop a wheel—a table for a philosopher's symposium.

Similarly, a skull might be seen crowned by a chaplet of dried roses, a carpe diem, though rarely as bedecked as Mexican printmaker José Guadalupe Posada's Catrina.

In Mesoamerican architecture, stacks of skulls (real or sculpted) represented the result of human sacrifices.

Pirates

editThe pirate death's-head epitomizes the pirates' ruthlessness and despair; their usage of death imagery might be paralleled with their occupation challenging the natural order of things.[7] "Pirates also affirmed their unity symbolically", Marcus Rediker asserts, remarking the skeleton or skull symbol with bleeding heart and hourglass on the black pirate ensign, and asserting "it triad of interlocking symbols—death, violence, limited time—simultaneously pointed to meaningful parts of the seaman's experience, and eloquently bespoke the pirates' own consciousness of themselves as preyed upon in turn. Pirates seized the symbol of mortality from ship captains who used the skull 'as a marginal sign in their logs to indicate the record of a death'"[8]

Religion

editSkull art is found in depictions of some Hindu Gods. Shiva has been depicted as carrying skull.[10] Goddess Chamunda is described as wearing a garland of severed heads or skulls (Mundamala). Kedareshwara Temple, Hoysaleswara Temple, Chennakeshava Temple, Lakshminarayana Temple are some of the Hindu temples that include sculptures of skulls and Goddess Chamunda.[11] The temple of Kali is veneered with skulls, but the goddess Kali offers life through the welter of blood.

In Vajrayana Buddhist iconography, skull symbolism is often used in depictions of wrathful deities and of dakinis.

In some Korean life replacement narratives, a person discovers an abandoned skull and worships it. The skull later gives advice on how to cheat the gods of death and prevent an early death.

Political symbol

editA skull was worn as a trophy on the belt of the Lombard king Alboin, it was a constant grim triumph over his old enemy, and he drank from it. In the same way a skull is a warning when it decorates the palisade of a city, or deteriorates on a pike at a Traitor's Gate. The Skull Tower, with the embedded skulls of Serbian rebels, was built in 1809 on the highway near Niš, Serbia, as a stark political warning from the Ottoman government. In this case the skulls are the statement: that the current owner had the power to kill the former. "Drinking out of a skull the blood of slain (sacrificial) enemies is mentioned by Ammianus and Livy,[12] and Solinus describes the Irish custom of bathing the face in the blood of the slain and drinking it."[13] The rafters of a traditional Jívaro medicine house in Peru, or in New Guinea.[14]

When the skull appears in Nazi SS insignia, the death's-head (Totenkopf) represents loyalty unto death.

Holidays

editSkulls and skeletons are the main symbol of the Day of the Dead, a Mexican holiday. Skull-shaped decorations called calaveras are a common sight during the festivities.

Other uses

editWhen tattooed on the forearm its apotropaic power is thought to help an outlaw biker cheat death.[15]

The skull and crossbones signify "Poison" when they appear on a glass bottle containing a white powder, or any container in general.

The skull that is often engraved or carved on the head of early New England tombstones might be merely a symbol of mortality, but the skull is also often backed by an angelic pair of wings, lofting mortality beyond its own death.

In pop culture

edit-

Zombie Cocktail in a skull-shaped glass

Skulls and memento mori, as for example the diamond-studded skull For the Love of God by Damien Hirst,[16] have become a popular trend in pop culture.

In fashion

edit-

Young African American boy with skull-jacket

-

Dog with skull fashion

-

Skull jacket made from fox-fur Locarno (2013)

-

Sneakers Crampons (photo: Tgiros)

-

Outfit at Whitby Goth Weekend, 2008

-

Bikers wore skull-bandanas before it became a fashion trend

Skulls have been also found on clothing items for men, women and children.[2] Some sources credited Alexander McQueen for introducing skulls as a fashion trend with stylized skulls, starting with skull-decorated bags and scarves. The trend is extant by the early 2010s.[17][18]

See also

edit- Danse macabre

- Death (personification)

- Death's head (disambiguation)

- Jolly Roger

- Life replacement narratives, Korean myths in which a skull saves a person who worships it

- Memento mori

- Punisher's skull emblem

- Skull and Bones

- Skull and crossbones (disambiguation)

- Skull art

- Skull cup, the use of a defeated enemy's skull as a drinking cup

- Symbols of death

- The Ambassadors (Holbein)

- Totenkopf, the German word for death's head

- Tzompantli, a type of wooden rack or palisade documented in several Mesoamerican civilizations, which was used for the public display of human skulls

- Vanitas

References

editFootnotes

edit- ^ (University of Wales, Bangor) "New function identified for an area of the brain" Archived December 6, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kearl, Michael C. (2 January 2015). "The proliferation of skulls in popular culture: a case study of how the traditional symbol of mortality was rendered meaningless". Mortality. 20 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/13576275.2014.961004.

- ^ Marche, Stephen (3 July 2008). "Have You Been Noticing a Lot of Skulls Lately?". Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ See Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia.

- ^ Bascom, William R. (11 March 1991), Ifá Divination: Communication Between Gods and Men in West Africa, Indiana UP, ISBN 0-253-20638-3

- ^ The Crypt: Church of the Immaculate. Official site of the Capuchins Archived July 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "In Virginia in 1720 one of the six pirates facing the gallows "called for a Bottle of Wine, and taking a Glass of it, he drank Damnation to the Governour and Confusion to the Colony", which the Rest pledg'd". (Marcus Rediker, "Under the Banner of King Death": The Social World of Anglo-American Pirates, 1716 to 1726" The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 38.2 (April 1981:203–227) p. 219.

- ^ Rediker 1981:221, and 223, quoting S. Charles Hill, "Episodes of piracy in Eastern waters", Indian Antiquary 49 (1920:37).

- ^ Andrews, Stefan (March 29, 2019). "Santa Muerte – The Story Behind the World's Most Popular Saint of Death". The Vintage News. Retrieved 2021-12-01.

- ^ Devdutt Pattanaik (2006). Shiva to Shankara: Decoding the Phallic Symbol. Indus Source. p. 49. ISBN 9788188569045.

- ^ Chugh, Lalit (23 May 2017). Karnataka's Rich Heritage – Temple Sculptures & Dancing Apsaras: An Amalgam of Hindu Mythology, Natyasastra and Silpasastra. Notion Press. p. 524. ISBN 9781947137363.

- ^ MacCulloch is referring to Livy xxiii.24, of events of 216 BCE: "Postumius died there fighting with all his might not to be captured alive. The Gauls stripped him of all his spoils and the Boii took his severed head in a procession to the holiest of their temples.There it was cleaned and the bare skull was adorned with gold, as is their custom. It was used thereafter as a sacred vessel on special occasions and as a ritual drinking-cup by their priests and temple officials."

- ^ J.A. MacCulloch, The Religion of the Ancient Celts 1911:239f.

- ^ F.W. Up De Graff. Head hunters of the Amazon: Seven Years of Exploration and Adventure, New York: Garden City 1925 pp. 273–283 Archived March 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Margo DeMello, Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community, (Duke University Press) 2000, ch. "Creation of Meaning" explores the semiotics of modern tattooing.

- ^ Hirst, Damien. "For the Love of God, 2007". Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Vaidyanathan, Rajini (12 February 2010). "Six ways Alexander McQueen changed fashion". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Gibson, Crystal. "Defend the Trend:Skulls". Retrieved 17 June 2013.

General

edit- Ariès, Philippe, L'Homme devant la mort: (Seuil, 1985), 2 vol. ISBN 2-02-008944-0, ISBN 2-02-008945-9

- Veyne, Paul (1987). A History of Private Life : 1. From Pagan Rome to Byzantium ( p. 208 illustrates the skull mosaic from Pompeii)