Thomas Slade Gorton III (January 8, 1928 – August 19, 2020) was an American lawyer and politician from Washington. A member of the Republican Party, he served as a member of the United States Senate from 1981 to 1987, and again from 1989 to 2001. He held both of the state's U.S. Senate seats in his career and was narrowly defeated for reelection twice, first in 1986 by Brock Adams and again in 2000 by Maria Cantwell following a recount, becoming the last Republican senator to date for each seat.

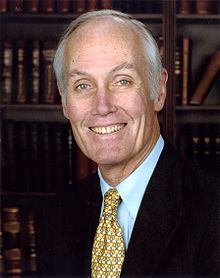

Slade Gorton | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Washington | |

| In office January 3, 1989 – January 3, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel J. Evans |

| Succeeded by | Maria Cantwell |

| In office January 3, 1981 – January 3, 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Warren Magnuson |

| Succeeded by | Brock Adams |

| 14th Attorney General of Washington | |

| In office January 15, 1969 – January 1, 1981 | |

| Governor | Daniel J. Evans Dixy Lee Ray |

| Preceded by | John O'Connell |

| Succeeded by | Ken Eikenberry |

| Majority Leader of the Washington House of Representatives | |

| In office January 9, 1967 – January 13, 1969 | |

| Preceded by | John L. O'Brien |

| Succeeded by | Stewart Bledsoe |

| Member of the Washington House of Representatives from the 46th district | |

| In office January 12, 1959 – January 13, 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Alfred E. Leland |

| Succeeded by | George W. Scott |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Slade Gorton III January 8, 1928 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | August 19, 2020 (aged 92) Clyde Hill, Washington, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Sally Jean Clark

(m. 1958; died 2013) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Nathaniel M. Gorton (brother) |

| Education | Dartmouth College (BA) Columbia University (JD) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1945–1946 (Army) 1953–1956 (Air Force) 1956–1980 (Reserve) |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | United States Air Force Reserve |

Early life and education

editGorton was born in Chicago, on January 8, 1928, and raised in the suburb of Evanston, Illinois, the son of Ruth (Israel) and Thomas Slade Gorton, Jr., descendant of one of the founders of the companies that would become Gorton's of Gloucester, and himself the founder that year of Slade Gorton & Co., another fish supplier.[1][2][3][4] His younger brother is Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts. He attended and graduated from Dartmouth College and subsequently from Columbia Law School. Gorton served in the United States Army from 1945 to 1946 and the United States Air Force from 1953 until 1956. He continued to serve in the Air Force Reserve Command until 1980 when he retired as a colonel.[2][citation needed]

Early career

editGorton practiced law and entered politics in 1958, being elected to the Washington House of Representatives, in which he served from 1959 until 1969, becoming one of its highest-ranking members.[5][2] He then served as Attorney General of Washington[2] from 1969 until he entered the United States Senate in 1981. During his three terms as attorney general, Gorton was recognized for taking the unusual step of appearing personally to argue the state's positions before the Supreme Court of the United States, and for prevailing in those efforts.[citation needed]

In 1970, Attorney General Gorton sued Major League Baseball for a violation of anti-trust laws after the loss of the Seattle Pilots, who were moved to Milwaukee after the league declined a bid from local ownership group. He hired trial lawyer William Lee Dwyer to oversee the case and eventually withdrew following the league's approval of a second expansion team—the Seattle Mariners, who began play in 1977.[6][7]

Years later, he approached Nintendo President Minoru Arakawa and Chairman Howard Lincoln in his search to find a buyer for the Mariners. Arakawa's father-in-law, Nintendo President Hiroshi Yamauchi, agreed to buy a majority stake in the team, preventing a potential move to Tampa.[8][9] Gorton later helped broker a deal between King County officials and Mariners ownership on what is now called T-Mobile Park.[10]

U.S. Senate campaigns

edit1980

editIn 1980, Gorton defeated longtime incumbent U.S. Senator and state legend Warren Magnuson by a 54% to 46% margin.

1986

editGorton was narrowly defeated by former U.S. Representative and United States Secretary of Transportation Brock Adams.[2]

1988

editGorton ran for the state's other Senate seat, which was being vacated by political ally Daniel J. Evans, in 1988 and won, defeating liberal Congressman Mike Lowry by a narrow margin.[2]

In the Senate, Gorton had a moderate-to-conservative voting record, and was derided for what some perceived as strong hostility towards Native tribes.[11][12][13] His reelection strategy centered on running up high vote totals in areas outside of left-leaning King County (home to Seattle).[14][15]

1994

editIn 1994, Gorton repeated the process, defeating then-King County Councilman Ron Sims by 56% to 44%.[2] He was an influential member of the United States Senate Committee on Armed Services as he was the only member of the committee during his tenure to have reached a senior command rank in the uniformed services (USAF).

Gorton campaigned in Oregon for Gordon H. Smith and his successful 1996 Senate run.[citation needed]

In 1999, Gorton was among ten Republican senators who voted against the charge of perjury during the Impeachment of Bill Clinton, although he voted for Clinton's conviction on the charge of obstruction of justice.[citation needed]

2000

editIn 2000, Democrat Maria Cantwell turned his "it's time for a change" strategy against him and won by 2,229 votes out of nearly 2.5 million cast.[16][17][2]

Furthermore, Washington's Native tribes strongly opposed Gorton in 2000 because he consistently tried to weaken Native sovereignty while in the Senate.[18]

Twice during his tenure in the Senate, Gorton sat at the Candy Desk.[citation needed]

Later career

editIn 2002, Gorton became a member of the 9/11 Commission, which issued its final report, the 9/11 Commission Report, in 2004.[19][2]

In 2005, Gorton became the chairman of the center-right Constitutional Law PAC, a political action committee formed to help elect candidates to the Washington State Supreme Court and Court of Appeals.[20]

Gorton was an advisory board member for the Partnership for a Secure America, a not-for-profit organization dedicated to recreating the bipartisan center in American national security and foreign policy. Gorton also served as a Senior Fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center.[21]

Gorton served on the board of trustees of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, which is a museum dedicated to the Constitution of the United States.[22]

Gorton represented Seattle in a lawsuit against Clay Bennett to prevent the Seattle SuperSonics relocation basketball franchise, in accordance to a contract that would keep the team in Climate Pledge Arena until 2010. The city settled with Bennett, allowing him to move the team to Oklahoma City for $45 million with the possibility for another $30 million.[23]

In 2010, the National Bureau of Asian Research founded the Slade Gorton International Policy Center. The Gorton Center is a policy research center, with three focus areas: policy research, fellowship and internship programs, and the Gorton History Program (archives).[24] In 2013 the Gorton Center was the secretariat for the ‘Commission on The Theft of American Intellectual Property’, in which Gorton was a commissioner.[25] Gorton was also a counselor at the National Bureau of Asian Research.[26]

In 2012, Gorton was appointed to the board of directors of Clearwire, a wireless data services provider.[27]

Gorton was a member of the board of the Discovery Institute, notable for its advocacy of the pseudoscience of intelligent design.

Gorton was also of counsel at K&L Gates LLP.[28]

Gorton opposed the candidacy of Donald Trump for President of the United States in 2016, instead writing in Independent candidate Evan McMullin.[29] He later supported the First impeachment of Donald Trump and urged other Republicans to join him.[30]

Personal life and death

editHe married the former Sally Jean Clark on June 28, 1958. They had three children, Sarah Nortz, Thomas Gorton, and Rebecca Dannaker. Sally Gorton died on July 20, 2013, one day before her 81st birthday.[31]

Gorton died after a brief illness with complications of Parkinson's disease on August 19, 2020 at the home of his daughter, Sarah Nortz in Clyde Hill, Washington, age 92.[32]

References

edit- ^ "Our Story". Slade Gorton & Co., Inc. Archived from the original on June 7, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gene Johnson (August 20, 2020). "Slade Gorton, former US senator, scion of fish stick family, dies at 92". Associated Press. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "Current Biography Yearbook". 1993.

- ^ Moritz, Charles (1962). Current Biography Yearbook. H. W. Wilson Company. ISBN 9780824201289.

- ^ "Former U.S. Senator Slade Gorton dies at age 92". king5.com. August 19, 2020. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Caldbick, John (February 12, 2013). "Seattle, King County, and State of Washington suspend lawsuit against baseball's American League on February 14, 1976, clearing way for Mariners". HistoryLink. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ Calkins, Matt (August 19, 2020). "Former U.S. Sen. Slade Gorton was there for the Mariners 'at every turn'". The Seattle Times. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ "Thiel: Strange saga of Slade Gorton and baseball – Sportspress Northwest". www.sportspressnw.com. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ "Guest: Hiroshi Yamauchi was Seattle's anchor to the Mariners". The Seattle Times. September 23, 2013. Archived from the original on December 17, 2022. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Brock, Corey. "Captain's Log: Remembering the man who thrice saved baseball in Seattle". The Athletic. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Westneat, Danny (September 14, 2008). "Where has McCain's honor gone?". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ "Senator Slade Gorton's bill is an assault on sovereignty". Indian Country Today (Lakota Times). May 1998. Retrieved September 15, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Kelley, Matt (April 30, 2000). "Tribes' Top Target in 2000: Sen. Slade Gorton". Los Angeles Times. pp. B6. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ Hendren, John (September 10, 2000). "Tough re-election race is nothing new to Gorton". The Seattle Times. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ Connelly, Joel (September 10, 2000). "Gorton is Already Lining Up Pieces for Re-election in 2000". The Seattle P-I. pp. A3. Retrieved September 15, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Balter, Joni (April 24, 2005). "Who is Maria Cantwell?". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2009. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ "Maria Cantwell (Dem)". The Washington Times. September 15, 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Getches, David H., Charles F. Wilkinson, Robert A. Williams, Jr. Cases and Materials on Federal Indian Law (2005). St. Paul: Thompson West. 5th ed. p. 29.

- ^ "National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States". 9-11commission.gov. August 21, 2004. Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Modie, Neil (November 24, 2005). "State PAC to push for right-wing judges". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ "Senior Fellows, Bipartisan policy Center". Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ^ "National Constitution Center, Board of Trustees". National Constitution Center Web Site. National Constitution Center. July 26, 2010. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Seattle, Bennett Slam Door on the Sonics". The Wall Street Journal. July 3, 2008. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ "Slade Gorton Policy Center Web site". Archived from the original on January 10, 2014.

- ^ "IP Commission Web Site". Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ "National Bureau of Asian Research Web Site". Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ "Clearwire Announces Appointment of Former U.S. Senator Slade Gorton to Company's Board of Directors (NASDAQ:CLWR)". Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ^ "K&L Gates Firm Bio". Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Strauss, Daniel (September 2, 2016). "Never Trump conservative McMullin makes Virginia ballot". Politico. Archived from the original on September 3, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Gorton, Slade (November 25, 2019). "My Fellow Republicans, Please Follow the Facts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ "Civic leader, political wife Sally Clark Gorton dies". The Seattle Times. July 22, 2013. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ "Former U.S. Sen. Slade Gorton, a towering figure in Washington state, dies at 92". Seattletimes.com. August 18, 2020. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

Further reading

edit- Hughes, John C., Slade Gorton: A Half Century in Politics (2011) (authorized biography) [ISBN missing]

External links

edit- Congressional Bio

- Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP ("K&L Gates") Lawyer Bio

- The Next Ten Years of Post-9/11 Security Efforts, Q&A with Slade Gorton (September 2011)

- Appearances on C-SPAN