This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

The small-world experiment comprised several experiments conducted by Stanley Milgram and other researchers examining the average path length for social networks of people in the United States.[1] The research was groundbreaking in that it suggested that human society is a small-world-type network characterized by short path-lengths. The experiments are often associated with the phrase "six degrees of separation", although Milgram did not use this term himself.

Historical context of the small-world problem

editGuglielmo Marconi's conjectures based on his radio work in the early 20th century, which were articulated in his 1909 Nobel Prize address,[2][failed verification] may have inspired[3] Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy to write a challenge to find another person to whom he could not be connected through at most five people.[4] This is perhaps the earliest reference to the concept of six degrees of separation, and the search for an answer to the small world problem.

Mathematician Manfred Kochen and political scientist Ithiel de Sola Pool wrote a mathematical manuscript, "Contacts and Influences", while working at the University of Paris in the early 1950s, during a time when Milgram visited and collaborated in their research. Their unpublished manuscript circulated among academics for over 20 years before publication in 1978. It formally articulated the mechanics of social networks, and explored the mathematical consequences of these (including the degree of connectedness). The manuscript left many significant questions about networks unresolved, and one of these was the number of degrees of separation in actual social networks.

Milgram took up the challenge on his return from Paris, leading to the experiments reported in "The Small World Problem" in the May 1967 (charter) issue of the popular magazine Psychology Today, with a more rigorous version of the paper appearing in Sociometry two years later. The Psychology Today article generated enormous publicity for the experiments, which are well known today, long after much of the formative work has been forgotten.

Milgram's experiment was conceived in an era when a number of independent threads were converging on the idea that the world is becoming increasingly interconnected. Michael Gurevich had conducted seminal work in his empirical study of the structure of social networks in his MIT doctoral dissertation under Pool. Mathematician Manfred Kochen, an Austrian who had been involved in statist urban design, extrapolated these empirical results in a mathematical manuscript, Contacts and Influences, concluding that, in an American-sized population without social structure, "it is practically certain that any two individuals can contact one another by means of at least two intermediaries. In a [socially] structured population it is less likely but still seems probable. And perhaps for the whole world's population, probably only one more bridging individual should be needed."[citation needed] They subsequently constructed Monte Carlo simulations based on Gurevich's data, which recognized that both weak and strong acquaintance links are needed to model social structure. The simulations, running on the slower computers of 1973, were limited, but still were able to predict that a more realistic three degrees of separation existed across the U.S. population, a value that foreshadowed the findings of Milgram.

Milgram revisited Gurevich's experiments in acquaintanceship networks when he conducted a highly publicized set of experiments beginning in 1967 at Harvard University. One of Milgram's most famous works is a study of obedience and authority, which is widely known as the Milgram Experiment.[5] Milgram's earlier association with Pool and Kochen was the likely source of his interest in the increasing interconnectedness among human beings. Gurevich's interviews served as a basis for his small world experiments.

Milgram sought to develop an experiment that could answer the small world problem. This was the same phenomenon articulated by the writer Frigyes Karinthy in the 1920s while documenting a widely circulated belief in Budapest that individuals were separated by six degrees of social contact. This observation, in turn, was loosely based on the seminal demographic work of the Statists who were so influential in the design of Eastern European cities during that period. Mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, born in Poland and having traveled extensively in Eastern Europe, was aware of the Statist rules of thumb, and was also a colleague of Pool, Kochen and Milgram at the University of Paris during the early 1950s (Kochen brought Mandelbrot to work at the Institute for Advanced Study and later IBM in the U.S.). This circle of researchers was fascinated by the interconnectedness and "social capital" of social networks.

Milgram's study results showed that people in the United States seemed to be connected by approximately three friendship links, on average, without speculating on global linkages; he never actually used the phrase "six degrees of separation". Since the Psychology Today article gave the experiments wide publicity, Milgram, Kochen, and Karinthy all had been incorrectly attributed as the origin of the notion of "six degrees"; the most likely popularizer of the phrase "six degrees of separation" is John Guare, who attributed the value "six" to Marconi.

The experiment

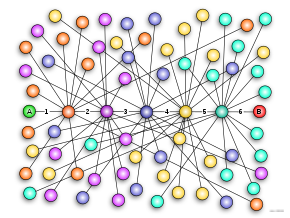

editMilgram's experiment developed out of a desire to learn more about the probability that two randomly selected people would know each other.[6] This is one way of looking at the small world problem. An alternative view of the problem is to imagine the population as a social network and attempt to find the average path length between any two nodes. Milgram's experiment was designed to measure these path lengths by developing a procedure to count the number of ties between any two people.

Basic procedure

edit- Though the experiment went through several variations, Milgram typically chose individuals in the U.S. cities of Omaha, Nebraska, and Wichita, Kansas, to be the starting points and Boston, Massachusetts, to be the end point of a chain of correspondence. These cities were selected because they were thought to represent a great distance in the United States, both socially and geographically.[4]

- Information packets were initially sent to "randomly" selected individuals in Omaha or Wichita. They included letters, which detailed the study's purpose, and basic information about a target contact person in Boston. It additionally contained a roster on which they could write their own name, as well as business reply cards that were pre-addressed to Harvard.

- Upon receiving the invitation to participate, the recipient was asked whether he or she personally knew the contact person described in the letter. If so, the person was to forward the letter directly to that person. For the purposes of this study, knowing someone "personally" was defined as knowing them on a first-name basis.

- In the more likely case that the person did not personally know the target, then the person was to think of a friend or relative who was more likely to know the target. They were then directed to sign their name on the roster and forward the packet to that person. A postcard was also mailed to the researchers at Harvard so that they could track the chain's progression toward the target.

- When and if the package eventually reached the contact person in Boston, the researchers could examine the roster to count the number of times it had been forwarded from person to person. Additionally, for packages that never reached the destination, the incoming postcards helped identify the break point in the chain.[citation needed]

Results

editShortly after the experiments began, letters would begin arriving to the targets and the researchers would receive postcards from the respondents. Sometimes the packet would arrive to the target in as few as one or two hops, while some chains were composed of as many as nine or ten links. However, a significant problem was that often people refused to pass the letter forward, and thus the chain never reached its destination. In one case, 232 of the 296 letters never reached the destination.[6]

However, 64 of the letters eventually did reach the target contact. Among these chains, the average path length fell around five and a half or six. Hence, the researchers concluded that people in the United States are separated by about six people on average. Although Milgram himself never used the phrase "six degrees of separation", these findings are likely to have contributed to its widespread acceptance.[4]

In an experiment in which 160 letters were mailed out, 24 reached the target in his home in Sharon, Massachusetts. Of those 24 letters, 16 were given to the target by the same person, a clothing merchant Milgram called "Mr. Jacobs". Of those that reached the target at his office, more than half came from two other men.[7]

The researchers used the postcards to qualitatively examine the types of chains that are created. Generally, the package quickly reached a close geographic proximity, but would circle the target almost randomly until it found the target's inner circle of friends.[6] This suggests that participants strongly favored geographic characteristics when choosing an appropriate next person in the chain.

Criticisms

editThere are a number of methodological criticisms of the small-world experiment, which suggest that the average path length might actually be smaller or larger than Milgram expected. Four such criticisms are summarized here:

- Judith Kleinfeld argues[8] that Milgram's study suffers from selection and non-response bias due to the way participants were recruited and high non-completion rates. First, the "starters" were not chosen at random, as they were recruited through an advertisement that specifically sought people who considered themselves well-connected. Another problem has to do with the attrition rate. If one assumes a constant portion of non-response for each person in the chain, longer chains will be under-represented because it is more likely that they will encounter an unwilling participant. Hence, Milgram's experiment should underestimate the true average path length. Several methods have been suggested to correct these estimates; one uses a variant of survival analysis in order to account for the length information of interrupted chains, and thus reduce the bias in the estimation of average degrees of separation.[9]

- One of the key features of Milgram's methodology is that participants are asked to choose the person they know who is most likely to know the target individual. But in many cases, the participant may be unsure which of their friends is the most likely to know the target. Thus, since the participants of the Milgram experiment do not have a topological map of the social network, they might actually be sending the package further away from the target rather than sending it along the shortest path. This is very likely to increase route length, overestimating the average number of ties needed to connect two random people. An omniscient path-planner, having access to the complete social graph of the country, would be able to choose a shortest path that is, in general, shorter than the path produced by a greedy algorithm that makes local decisions only.

- A description of heterogeneous social networks still remains an open question. Though much research was not done for a number of years, in 1998 Duncan Watts and Steven Strogatz published a breakthrough paper in the journal Nature. Mark Buchanan said, "Their paper touched off a storm of further work across many fields of science" (Nexus, p60, 2002). See Watts' book on the topic: Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age.

- Some communities, such as the Sentinelese, are completely isolated, disrupting the otherwise global chains. Once these people are discovered, they remain more "distant" from the vast majority of the world, as they have few economic, familial, or social contacts with the world at large; before they are discovered, they are not within any degree of separation from the rest of the population. However, these populations are invariably tiny, rendering them of low statistical relevance.

In addition to these methodological criticisms, conceptual issues are debated. One regards the social relevance of indirect contact chains of different degrees of separation. Much formal and empirical work focuses on diffusion processes, but the literature on the small-world problem also often illustrates the relevance of the research using an example (similar to Milgram's experiment) of a targeted search in which a starting person tries to obtain some kind of resource (e.g., information) from a target person, using a number of intermediaries to reach that target person. However, there is little empirical research showing that indirect channels with a length of about six degrees of separation are actually used for such directed search, or that such search processes are more efficient compared to other means (e.g., finding information in a directory).[10]

Influence

editThe social sciences

editThe Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell, based on articles originally published in The New Yorker,[11] elaborates on the "funneling" concept. Gladwell condenses sociological research, which argues that the six-degrees phenomenon is dependent on a few extraordinary people ("connectors") with large networks of contacts and friends: these hubs then mediate the connections between the vast majority of otherwise weakly connected individuals.

Recent work in the effects of the small world phenomenon on disease transmission, however, have indicated that due to the strongly connected nature of social networks as a whole, removing these hubs from a population usually has little effect on the average path length through the graph (Barrett et al., 2005).[citation needed]

Mathematicians and actors

editSmaller communities, such as mathematicians and actors, have been found to be densely connected by chains of personal or professional associations. Mathematicians have created the Erdős number to describe their distance from Paul Erdős based on shared publications. A similar exercise has been carried out for the actor Kevin Bacon and other actors who appeared in movies together with him — the latter effort informing the game "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon". There is also the combined Erdős-Bacon number, for actor-mathematicians and mathematician-actors. Players of the popular Asian game Go describe their distance from the great player Honinbo Shusaku by counting their Shusaku number, which counts degrees of separation through the games the players have had.[12]

Current research on the small-world problem

editThe small-world question is still a popular research topic today, with many experiments still being conducted. For instance, Peter Dodds, Roby Muhamad, and Duncan Watts conducted the first large-scale replication of Milgram's experiment, involving 24,163 e-mail chains and 18 targets around the world.[13]

Dodds et al. also found that the mean chain length was roughly six, even after accounting for attrition. A similar experiment using popular social networking sites as a medium was carried out at Carnegie Mellon University. Results showed that very few messages actually reached their destination. However, the critiques that apply to Milgram's experiment largely apply also to this current research.[citation needed]

Network models

editIn 1998, Duncan J. Watts and Steven Strogatz from Cornell University published the first network model on the small-world phenomenon. They showed that networks from both the natural and man-made world, such as power grids and the neural network of C. elegans, exhibit the small-world phenomenon. Watts and Strogatz showed that, beginning with a regular lattice, the addition of a small number of random links reduces the diameter—the longest direct path between any two vertices in the network—from being very long to being very short.[14] The research was originally inspired by Watts' efforts to understand the synchronization of cricket chirps, which show a high degree of coordination over long ranges as though the insects are being guided by an invisible conductor. The mathematical model which Watts and Strogatz developed to explain this phenomenon has since been applied in a wide range of different areas. In Watts' words:[15]

I think I've been contacted by someone from just about every field outside of English literature. I've had letters from mathematicians, physicists, biochemists, neurophysiologists, epidemiologists, economists, sociologists; from people in marketing, information systems, civil engineering, and from a business enterprise that uses the concept of the small world for networking purposes on the Internet.

Generally, their model demonstrated the truth in Mark Granovetter's observation that it is "the strength of weak ties"[16] that holds together a social network. Although the specific model has since been generalized by Jon Kleinberg[citation needed], it remains a canonical case study in the field of complex networks. In network theory, the idea presented in the small-world network model has been explored quite extensively. Indeed, several classic results in random graph theory show that even networks with no real topological structure exhibit the small-world phenomenon, which mathematically is expressed as the diameter of the network growing with the logarithm of the number of nodes (rather than proportional to the number of nodes, as in the case for a lattice). This result similarly maps onto networks with a power-law degree distribution, such as scale-free networks.

In computer science, the small-world phenomenon (although it is not typically called that) is used in the development of secure peer-to-peer protocols, novel routing algorithms for the Internet and ad hoc wireless networks, and search algorithms for communication networks of all kinds.

In popular culture

editSocial networks pervade popular culture in the United States and elsewhere. In particular, the notion of six degrees has become part of the collective consciousness. Social networking services such as Facebook, Linkedin, and Instagram have greatly increased the connectivity of the online space through the application of social networking concepts.

See also

edit- Bacon number – Parlor game on degrees of separation

- Dunbar's number – Suggested cognitive limit important in sociology and anthropology

- Erdős number – Closeness of someone's association with mathematician Paul Erdős

- Erdős–Bacon number – Closeness of someone's association with mathematician Paul Erdős and actor Kevin Bacon

- Percolation theory – Mathematical theory on behavior of connected clusters in a random graph

- Personal network – set of human contacts known to an individual

- Random walk – Process forming a path from many random steps

- Random graph – Graph generated by a random process

- Richard Gilliam – American writer

References

edit- ^ Milgram, Stanley (May 1967). "The Small World Problem". Psychology Today. Ziff-Davis Publishing Company.

- ^ Guglielmo Marconi, 1909, Nobel Lecture, Wireless telegraphic communication.

- ^ Evans, David C (2017). Six degrees of recommendation. Bottlenecks.

- ^ a b c Barabási, Albert-László Archived 2005-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. 2003. "Linked: How Everything is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life. Archived 2007-01-03 at the Wayback Machine" New York: Plume.

- ^ "Milgram Basics - Dr. Thomas Blass Presents: Stanley Milgram .com". Archived from the original on 2008-07-31. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ a b c Travers, Jeffrey; Milgram, Stanley (1969). "An Experimental Study of the Small World Problem". Sociometry. 32 (4): 425–443. doi:10.2307/2786545. JSTOR 2786545.

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm. "The Law of the Few". The Tipping Point. Little Brown. pp. 34–38.

- ^ Kleinfeld, Judith (March 2002). "Six Degrees: Urban Myth?". Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers, LLC. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ Schnettler, Sebastian. 2009. "A small world on feet of clay? A comparison of empirical small-world studies against best-practice criteria." Social Networks, 31(3), pp. 179-189, doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2008.12.005

- ^ Schnettler, Sebastian. 2009. "A structured overview of 50 years of small-world research" Social Networks, 31(3), pp. 165-178, doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2008.12.004

- ^ Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg Archived 2007-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Laird, Roy. "What's Your "Shusaku Number?" « American Go E-Journal". American Go Association. No. 24 July 2011. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ "An Experimental Study of Search in Global Social Networks". Science 8 August 2003: Vol. 301 no. 5634 pp. 827-829DOI:10.1126/science.1081058

- ^ Watts, Duncan J.; Strogatz, Steven H. (June 1998). "Collective dynamics of 'small-world' networks". Nature. 393 (6684): 440–442. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..440W. doi:10.1038/30918. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 9623998.

- ^ Shulman, Polly (1 December 1998). "From Muhammad Ali to Grandma Rose". DISCOVER magazine. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ^ Granovetter, Mark S. (1973). "The Strength of Weak Ties". American Journal of Sociology. 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469. JSTOR 2776392.

External links

edit- Planetary-Scale Views on an Instant-Messaging Network

- Theory tested for specific groups:

- The Oracle of Bacon at Virginia

- The Oracle of Baseball

- The Erdős Number Project

- The Oracle of Music

- CoverTrek - linking bands and musicians via cover versions

- Science Friday: Future of Hubble / Small World Networks

- "Knock, Knock, Knocking on Newton's Door" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-24. (223 KiB) – article published in Defense Acquisition University's journal Defense AT&L, proposing "small world / large tent" social networking model