Great and Little Kimble cum Marsh is a civil parish in central Buckinghamshire, England. It is located 5 miles (8 km) to the south of Aylesbury. The civil parish altogether holds the ancient ecclesiastical villages of Great Kimble, Little Kimble, Kimblewick and Marsh, and an area within Great Kimble called Smokey Row. The two separate parishes with the same name were amalgamated in 1885, but kept their separate churches, St Nicholas for Great Kimble on one part of the hillside and All Saints for Little Kimble on other side at the foot of the hill.

| Great and Little Kimble cum Marsh | |

|---|---|

Great Kimble Church | |

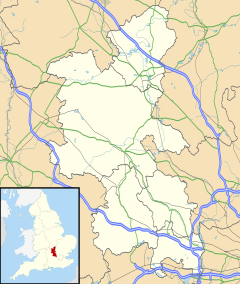

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Population | 1,026 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP824065 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | AYLESBURY |

| Postcode district | HP17 |

| Dialling code | 01296 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

They fall within the Hundred of Stone, which was originally one of the Three Hundreds of Aylesbury, later amalgamated into the Aylesbury Hundred. The parishes lie between Monks Risborough and Ellesborough and, like other parishes on the north side of the Chilterns, their topography are that of long and narrow strip parishes, including a section of the scarp and extending into the vale below. In length the combined parish extends for about 4+1⁄4 miles (6.8 km) from near the Bishopstone Road beyond Marsh to the far end of Pulpit Wood near the road from Great Missenden to Chequers but it is only a mile wide at the widest point. The village of Great Kimble lies about 5.5 miles (8.9 kilometres) south of Aylesbury and about 2.5 miles (4.0 kilometres) north east from Princes Risborough on the A4010 road.

The parishes of Kimble have first and foremost been a farming community for nearly two thousand years [2] and are something of a historical interest dating back chronologically to Celtic Ages. At the summit of Pulpit Hill in Great Kimble there is a prehistoric Hillfort. When Britain was taken over by Roman occupation a Roman villa was erected in Little Kimble and near St Nicholas's church is a tumulus or a burial mound commonly known as 'Dial Hill' from the same period. After the Norman Conquest of England the parishes were most likely considered too small for a stone fort, so they would have probably kept a motte and bailey castle that later developed into a moated site for a medieval dwellinghouse.

It was here that John Hampden refused to pay his ship-money in 1635, one of the incidents which led to the English Civil War.

The majority of the land surrounding the village and some local amenities such as the pub and the petrol station were once owned by the Russel family until they were lost many years ago to excessive gambling.

Origin and Toponym of Kimble

editThe exact origin of the name is unknown though there have been many competing theories.

The name 'Kimble' is said to have been first established around Anglo-Saxon times when it appeared with the name 'Cyne Belle', which corresponds to two Anglo-Saxon words. 'Cyne' (meaning royal) and 'Belle' (meaning 'bell')[3] though the exact reason for calling the place 'Cyne Belle' is not certain. The original theory was that the name 'Cyne Belle' originated from the Celtic leader Cunobeline though this has never been proved chronologically. The modern name Cymbeline originates from Shakespeare's play, his proper-spelt name at the time Cunobeline (Cunobelinus in Latin by the Romans) was King of the Celtic 'Cassivellauni' tribe from about 4 BC to about 41 AD. Cunobeline is most likely known to have owned the hillfort on Pulpit Hill. His tribe occupied part of southern Britain at that time, which was about 800 years before the Anglo-Saxon name 'Cyne Belle' first appeared, with 400 years of Roman occupation and several invasions from Europe in the intervening period.[4]

Mawer and Stenton, who published their book on the Place Names of Buckinghamshire in 1925, thought that 'belle' could have meant a hill and suggested that the conspicuous hill at Kimble (now known as Cymbeline's Castle or Cymbeline's Hill) would have impressed itself on the minds of the first settlers and might have called it 'royal' (or given it royal status) for being the largest visible hill in the locality, or that it earned the epithet by reason of some royal burial or other unknown event.[3] However the possibility of a 'royal burial' could have been that of Cunobeline's son Togodumnus who was a short-lived leader before the Roman Campaign, which by local legends has it, died at a battle in Kimble and might've been buried here.[5]

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names, first published in 1951, interpreted the name as "Royal bell-shaped hill" and the later Oxford Companion to Names (2002) also gives the same meaning.[6] The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place Names (2004) gives the translation "Royal Bell, the bell-shaped hill" and says that it is derived from the Old English cyne + belle, probably used as a place-name, and that the reference is to the prominent Pulpit Hill crowned with its hillfort, suggesting that 'royal' referred to Great Kimble for distinction from Little Kimble.[7]

Not all these explanations are completely convincing and there may be more to be said.[8] The precise nature of the Royal Bell in the minds of the inhabitants of Kimble in the 9th century or earlier remains something of a mystery. It must be remembered that Pulpit Hill (or part of it) might then have been unwooded open grassland,[9] which would have made the shape of the hill more apparent from below and the hillfort on the summit (already a thousand years old) would in that case have been clearly visible and impressive and might well have been thought to be a royal castle.

Prehistoric Hillfort on Pulpit Hill

editThis hillfort is in Pulpit Wood on the summit of Pulpit Hill in Great Kimble, about 3/4 of a mile south-east of St Nicholas' church.[10] It is 813 feet (248 m) above ordnance datum. It has never been excavated and its precise date is unknown, though almost certainly built during the 1st millennium B.C. Hillforts are usually attributed to the Iron Age, but there are a series of hillforts at intervals along the Chiltern ridge and that at Ivinghoe Beacon, which is not far away, has been excavated and found to have been built in the late Bronze Age.[11]

The Pulpit Hill fort follows the contours at the top of the hill and has an area of 0.9 hectares (2.2 acres). The boundary is roughly D-shaped (nearly square) with maximum internal dimensions of 104 by 98 metres (341 ft × 322 ft). There are still double ramparts and ditches on the North and South East sides, but on the North and South West sides, face very steep slopes down the hill. The outer rampart is hardly apparent and there is no sign of an outer ditch. The builders seem to have relied on the steep natural slopes on these sides, though the original ditches may have been eroded away. The entrance is on the South East side, where the ground is level. The ramparts remain imposing after (probably) about 2,500 years. Although now mere banks of earth, they would originally been revetted with timber and boxed in, so that the faces would have been vertical.[12]

The fort, though in a commanding location, was probably not primarily intended as a fortress in time of war. With its deep embedded location in Pulpit Wood, it is likely to have been either a hunting lodge or a place for storing agricultural produce and used to store grain and to enclose animals from farms in the district (perhaps as protection from cattle raids), as well as being a defensible site if and when the need arose.

There is also evidence that hillforts were used for ritual activities, possibly for religious purposes connected with agriculture. In similar terrain further south of Kimble appears Whiteleaf Cross which has been referenced as a phallic symbol.[13]

Roman Villa and burial mound

editAt Little Kimble on the east side of the church are indications of the site of a Roman villa. Foundations, wall plaster, tesselated floors, tiles, coins and pottery have been found there over the past two hundred years, but it has never been properly excavated in modern times.[14]

It would have been the dwelling of a substantial landowner, farming a fair-sized estate, probably surrounded by the principal farm buildings. Villas are more common on the south side of the Chilterns, but there are 7 or 8 along the north side below the scarp of which this is one. The reason for this was because back in the Mediterranean climate having a dwelling within the shadow of a hillside could be comfortable in the hot summer weather.[5] (There was another villa built on the north side at Saunderton). Surplus produce would have been sold at Verulamium (St Albans).[15]

A barrow or funeral mound lies on the west side of Great Kimble church of St Nicholas, adjoining the churchyard and fronting on Church Lane. It is known as Dial Hill (from the sundial formerly erected above it) and is believed to date from the Roman period, but has not been properly excavated. Although there were limited amateur investigations in 1887 and 1950. It is scheduled as an ancient monument by English Heritage and their description suggests that it might have held the body of the occupant of the Roman villa.[16]

Medieval and later times

editNorman Conquest and Domesday Book

editBefore the Norman conquest of England in 1066 both Great Kimble and Little Kimble were owned by royal Thegns, Sired at Great Kimble and Brictric at Little Kimble. Both were dispossessed by the new king, William of Normandy.

Great Kimble (Chenebelle in Domesday Book) was given to Walter Giffard, Lord of Longueville in Normandy, who received a total of 107 lordships of land in England, 48 of them in Buckinghamshire.[17] He passed Great Kimble to one of his own followers, sub-granting it to Hugh of Bolbec (a town in Normandy near the mouth of the Seine). Little Kimble (Chenebelle parva) went to Thurston son of Rolf, who sub-granted it to one Albert.

Great Kimble was assessed for taxation at 20 hides, while Little Kimble answered for only 10 hides. The information given in Domesday Book is summarised below. (Numbers of people refer only to the heads of families).[18]

| Great Kimble | Little Kimble | Marsh | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tax assessment | 20 hides | 10 hides | |

| Land for | 11 1/2 ploughs | 10 ploughs | |

| Ploughs on demesne land | 2 (+1 possible) | 2 (+2 possible) | |

| Villagers | 22 | 10 | |

| Smallholders | 8 | 1 | |

| Ploughs of Villagers & Smallholders | 8 1/2 ploughs | 3 ploughs +3 possible | |

| Slaves | 6 | 2 | |

| Meadow (for plough teams of 8 oxen) | 11 ploughs | 10 ploughs | |

| Other assets | Wood for fences | 1 mill at 16s. | |

| Value in 1066 & 1087 | £10 always | £5 (£6 before 1066) |

Motte and Bailey Castle

editBehind the church at Little Kimble to the east are mounds and banks in the grass which are all that remain of a motte and bailey castle, which would have been built at the order of the Normans soon after the conquest. These timber castles were built all over England and consisted of a high mound (the Motte), surmounted by a wooden tower, with subsidiary buildings surrounded by a rampart with palisades (the Bailey). At Little Kimble there was a motte, which is still 15 feet high, and two separate baileys, but the layout is not easy to recognise on the ground.[19]

Unlike large stone castles, which were built later at strategic points, these wooden forts were built for the local purposes of the manor rather than for military reasons. The Norman landholder, who was surrounded by hostile Englishmen, wanted a safe residence for himself.[20]

Later Manorial history

editThe later manorial history of Great Kimble is complicated because various sub-manors were created (known as Whitinghams Manor (or Fenels Grove), Uptons Manor and Marshals) and they each descended in different lines. By the 17th century they had come together again and the manor of Great Kimble was held by the Hampdens of Great Hampden and later sold, in 1730, to Sarah Dowager Duchess of Marlborough. Her successors sold it in 1803 to Scrope Bernard (later Sir Scrope Bernard-Morland, a Baronet), who had been lord of the manor of Little Kimble since 1792, He held both manors until his death in 1830 and they were then sold to Robert Greenhill Russell (created a Baronet in 1831). He lived at Chequers Court and already owned the neighbouring manor of Ellesborough in succession to Sir George Russell. The memory of Scrope Bernard and Sir George Russell was preserved in the names of two public houses, the §s at Great Kimble (now closed) and the Russell Arms at Butlers Cross in Ellesborough.[21]

Churches

editSt Nicholas Church, Great Kimble

editThis church in the 12th century probably consisted only of a nave without aisles and a small chancel. In the middle of the 13th century the north and south aisles were added with the nave arcades and the nave may have been lengthened by one bay. In the first half of the 14th century the chancel arch was added and the chancel rebuilt. The west tower and clerestorey were added later in that century. The nave was re-roofed in the 16th century.

The font (late 12th century) is a finely carved example of the local "Aylesbury" type.

The church was completely restored by J.P. Seddon in 1876–81. All the flint and stone exterior is of that date and the chancel and its aisles were rebuilt. A modern roof was built over the 16th century nave roof.[22]

All Saints Church, Little Kimble

editA church with chancel and nave existed before the mid-13th century, when the chancel was widened and the chancel arch inserted. The larger window and lowside window in the north wall of the chancel are early 14th century. The north and south porches and the doors and windows of the nave date from the early to mid 14th century.

There is a simple font of the late12th or early 13th century and in the chancel are 13th century medieval tiles of Chertsey Abbey type (possibly obtained from the ruins of Chertsey Abbey).

The interior is decorated with the remains of early 14th century wall paintings, most of which appear to have represented saints (the church is dedicated to All Saints). They include St Francis preaching to the birds and a large figure of St George, but not all can be identified. There seems to have been a doom on the west wall, where a devil is pushing two women into the mouth of Hell.[23]

Free Church

editThere is a small chapel in the Tudor style, built in 1922, to the west of the railway bridge at Little Kimble.[24]

St Faiths in Marsh was a small chapel and reading room. It was deconsecrated and became a private house in the twentieth century

Public Houses

editThe Swan in Great Kimble is the only surviving public house. The Prince of Wales, a thatched 1880's pub in Marsh, is in its original Grade II listed form, but currently closed. Mr Horace King was the last active landlord from 1964 to 2015.

Great Kimble previously had the Bernard Arms known for its connections to Chequers, the Prime Minister's country house nearby. It was the oldest public house in the parish, originally called the "Bear and Cross". It hosted Harold Wilson, John Major and Boris Yeltsin, the Russian President amongst other prominent visitors.

The Crown was on the Aylesbury Road, just beyond the railway bridge at Clanking. After a period as the Kimble Tandoori, it was demolished to make way for residential properties.

The Old Queens Head in Marsh suffered a similar fate.

John Hampden and Ship-money

editGreat Kimble has a special claim to fame as the parish where John Hampden refused to pay his ship-money in January 1635/6.[26] King Charles I, attempting to govern the country without a parliament, needed money to improve the navy and tried to raise it by levying "ship-money" from all the counties of England. Although the writ requiring the payments was worded as imposing an obligation on each county to provide a ship, in fact the money raised went straight to the treasurer of the Navy and was seen as being a tax.[27] It was a long established principle of the constitution that no tax could be raised by the king without the consent of parliament.

Each county had to raise a stated sum which was then divided between all the parishes in the county. Each parish appointed two Assessors to divide this liability between the individual landowners. John Hampden, who owned land in several parishes in Buckinghamshire, was assessed to £8.4s in his own parish of Great Hampden and he paid this and other assessments in full, showing that he was not objecting to the amount nor rejecting an obligation to defend his country. But in two parishes, where he owned less land, he refused payment on the point of principle and others followed his example. The two parishes where he refused payment were Great Kimble, where he was assessed to pay £1.11s.6d, and Stoke Mandeville, where his liability was £1.[27]

The Assessors for Great Kimble were required to prepare a list of persons failing to pay and this was issued at Great Kimble on 25 January 1635/6. At the head of the list is 'John Hampden 31s.6d.' followed by thirty other names assessed for smaller amounts including the two Assessors themselves and the two parish constables responsible to collect the money.[28]

People throughout the country were refusing payment and the king decided to select one man to be sued in a test case before all the judges in the Court of Exchequer Chamber. He selected John Hampden as the defendant in respect of the round sum of one pound assessed upon him at Stoke Mandeville. (The case did not mention the Great Kimble assessment).[29] Judgment was given for the King but only by a majority decision of seven judges to five, which was seen throughout the country as a moral defeat for the King and was followed by more refusals to pay.

Although the case referred only to Stoke Mandeville, Thomas Carlyle made Great Kimble famous with his description of what had happened, "there, in the cold weather, at the foot of the Chiltern Hills."[30]

Education

editGriffin House School, formerly Ladymede School, an independent co-educational school, is located in Little Kimble.[31] It has a capacity of just over 100 day students from ages 3–11.

Notable pupils of Ladymede School

editNotable people

editTransport

editThe main A4010 road runs through Great and Little Kimble cum Marsh, as does the Chiltern railway line between Aylesbury and Princes Risborough. Where the main road meets the railway is Little Kimble railway station, which has been in operation since 1872, although the station buildings are now a private dwelling. There is a level crossing at Marsh.

References

editBooks referred to in the notes

edit- Archaeology of the Chilterns from the Ice Age to the Norman Conquest. The; edited by Keith Branigan (Chess Valley Architectural & Historical Society. 1994)

- Armitage, Ella S.: The Norman Castles of the British Isles (London. 1912)

- Barker, Louise: Pulpit Hill, Great and Little Kimble, Buckinghamshire (English Heritage Archaeological Investigation Report series AI/16/2001) (English Heritage. 2001)

- Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names based on the collections of the English Place-Name Society, ed: Victor Watts (Cambridge University Press. 2004)

- Carlyle, Thomas: The Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell (London. 1904 edition, edited by S.C.Lomas) (originally published 1845)

- Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names, ed: Eilert Ekwal (Oxford University Press. 1951)

- Domesday Book vol 13 Buckinghamshire. Text & translation edited by John Morris (Phillimore, Chichester. 1978)

- Forde-Johnstone, James: Hillforts of the Iron Age in England & Wales. A survey of the surface evidence (Liverpool U.P. 1976)

- Lipscomb, George: The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham (2 volumes. London. 1847)

- Mawer, A. and Stenton, F.M: The Place Names of Buckinghamshire (Cambridge, 1925)

- Nugent, Lord: Some Memorials of John Hampden, his party and his times. 2 volumes (London. 1832)

- Oxford Companion to Names, ed:, Patrick Hanks, Flavia Hodges, A. D. Mills and Adrian Room (Oxford University Press. 2002)

- Pevsner, Nikolaus & Elizabeth Williamson: Buckinghamshire (The Buildings of England – Penguin Books. 2nd edition. 1994)

- RCHMB = Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England): An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Buckinghamshire, Volume 1 (1912)

- Russell, Conrad: Hampden, John (1595–1643) in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 24, pp. 975–984 (and in Online edition. 2008)

- VHCB = Victoria History of the County of Buckingham, Volume 2, ed: William Page F.S.A. (1908)

Notes

edit- ^ "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Roger Howgate: 'Kimble's Journey' 'in' The World of Piers the Ploughman pp. 02

- ^ a b Mawer & Stenton p. 13

- ^ Lipscomb Vol.2 p. 341 mentioned it as a conjecture in 1847

- ^ a b Roger Howgate: 'Kimble's Journey' 'in' The World of Piers the Ploughman pp. 04

- ^ Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names under 'Kimble' Oxford Dictionary of Names – Place Name Section – p. 1093

- ^ Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names under Kimble, Bucks

- ^ Mawer & Stenton (p. 13) thought certainty was not possible.

- ^ Barker p. 17

- ^ Louise Barker's report for English Heritage (2001) contains a full description and survey of the site, with plans and photographs.

- ^ Stewart Bryant: 'From Chiefdom to Kingdom' in Archaeology of the Chilterns, p. 52

- ^ On hillforts generally, see Forde-Johnstone

- ^ Stewart Bryant: 'From Chiefdom to Kingdom' in Archaeology of the Chilterns, pp. 52–53

- ^ RCHM Volume 1 p. 164,(3)

- ^ Keith Branigan: 'The Impact of Rome' in Archaeology of the Chilterns pp. 102–09

- ^ "English Heritage Home Page". English Heritage.

- ^ The Complete Peerage, ed. the Hon Vicary Gibbs, Volume II (1912) pp. 386–87

- ^ Domesday Book Vol.13: Land of Walter Giffard 14.2 & Land of Thurston son of Rolf 35

- ^ Pevsner & Williamson p. 439. The 1/2500 Ordnance Survey map shows the layout.

- ^ Armitage p. 85

- ^ For the manorial history of Great Kimble see VHCB pp. 298–302. For Little Kimble see VHCB pp. 303–04

- ^ RCHM vol.1 p. 164. Pevsner & Williamson p. 350

- ^ RCHM vol.1 pp. 166–67. Pevsner & Wiiliamson p. 439

- ^ Pevsner & Williamson p. 439

- ^ The facsimile is reproduced from Lord Nugent's book facing page 228 where it is stated to be derived from the original return which was among the papers of Sir Peter Temple at Stowe.

- ^ The date is often stated as January 1635. This is the Old Style (as would have been used at the time), when the year did not change until 25 March. Under the present New Style (when the year changes on 1 January) it would have been 1636.

- ^ a b Russell pp. 979–80

- ^ Nugent p. 229

- ^ The case is reported in full with the arguments of Counsel and the opinions of the judges in State Trials Volume 3, p. 825ff

- ^ Carlyle Vol.1, pp. 82–83

- ^ "Griffin House School - Home". www.griffinhouseschool.co.uk.

- ^ Howard-Gordon, Frances (22 December 2007). "Obituary: Arabella Churchill". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2010.