The United States has inherited sodomy laws which constitutionally outlawed a variety of sexual acts that are deemed to be illegal, illicit, unlawful, unnatural and/or immoral from the colonial-era based laws in the 17th century.[1] While they often targeted sexual acts between persons of the same sex, many sodomy-related statutes employed definitions broad enough to outlaw certain sexual acts between persons of different sexes, in some cases even including acts between married persons.

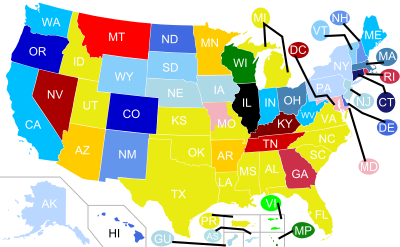

Through the mid to late 20th century, the gradual decriminalization of American sexuality law led to the elimination of anti-sodomy laws in most U.S. states. During this time, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of its sodomy laws in Bowers v. Hardwick in 1986. However, in 2003, the Supreme Court came to a new opinion and reversed the decision with Lawrence v. Texas, invalidating all sodomy laws in the remaining 14 states: Alabama, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Utah and Virginia.

History

editUp to Lawrence v. Texas

editColin Talley argues that the sodomy statutes in colonial America in the 17th century were largely unenforced. The reason he argues is that male-male eroticism did not threaten the social structure or challenge the gendered division of labor or the patriarchal ownership of wealth.[2] There were gay men on General Washington's staff and among the leaders of the new republic,[3] even though in Virginia there was a maximum penalty of death for sodomy. In 1779, Thomas Jefferson tried to reduce the maximum punishment to castration.[4] It was rejected by the Virginia legislature.[5] Justice Anthony Kennedy authoring the majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas stated that American laws targeting same-sex couples did not develop until the last third of the 20th century and also wrote that:[6]

Early American sodomy laws were not directed at homosexuals as such but instead sought to prohibit nonprocreative sexual activity more generally, whether between men and women or men and men. Moreover, early sodomy laws seem not to have been enforced against consenting adults acting in private. Instead, sodomy prosecutions often involved predatory acts against those who could not or did not consent: relations between men and minor girls or boys, between adults involving force, between adults implicating disparity in status, or between men and animals.

In 1950, New York enacted a new statute that divided the crime of sodomy into 3 degrees. First degree sodomy, with a maximum penalty of 20 years imprisonment, is defined as being done by force as in rape, or an act with an animal or a dead body. Second degree sodomy, with a maximum penalty of 10 years imprisonment, includes acts per os or per anum by a person over 21 years old with a person under 18 years old. Third degree sodomy, which is a misdemeanor with a maximum of 6 months in prison, is any act per os or per anum not amounting to first or second degree sodomy. With this new law, New York became the first state to reduce the crime of sodomy from a felony to a misdemeanor. A psychopathic offender law was included with this statute, but covered only sexual acts with minors or with the use of force or threats. In 1950, the Attorney General issued an opinion that the governing sodomy law covered both participants in an act of fellatio, the wording of the law being broader for oral sex than for anal. This opinion would be affirmed by a court interpretation more than a decade later.

In 1965, New York enacted a new statute repealing the crime of sodomy. Due to opposition to repealing the crime of sodomy, New York enacted a new statute at the same time that criminalized sodomy and reduced the maximum penalty from 6 months to 3 months, along with excluded married couples. It created the category of sexual misconduct, defined as engaging in sexual intercourse with another person without such person's consent and engaging in sexual conduct with an animal or a dead human body, which became a class A misdemeanor. Since the new statute repealing the crime of sodomy would only be effective on September 1, 1967, it never took effect.

Prior to 1962, sodomy was a felony in every state punished by a lengthy term of imprisonment or hard labor. In that year, the Model Penal Code (MPC) — developed by the American Law Institute to promote uniformity among the states as they modernized their statutes — struck a compromise that removed consensual sodomy from its criminal code while making it a crime to solicit for sodomy. In 1962, Illinois adopted the recommendations of the Model Penal Code and thus became the first state to remove criminal penalties for consensual sodomy from its criminal code,[7] almost a decade before any other state. Over the years, many of the states that did not repeal their sodomy laws had enacted legislation reducing the penalty.

On March 12, 1971, the Idaho House of Representatives voted was 55-5 in favor of House Bill 161, which enacted the entire Model Penal Code (MPC) in Idaho, which included repealing common-law crimes and the "crime against nature" law. The bill passed the Idaho Senate on March 25, 1971 and the vote was 34-1. It was signed on April 9, 1971 by Governor Cecil Andrus. It took effect on January 1, 1972. On January 25, 1972, the Idaho House voted was 44-28 in favor of House Bill 101, which repealed the provisions of House Bill 161, which had adopted the MPC. The bill passed the Idaho Senate on March 27, 1972 and the vote was 30-5. It was signed on March 27, 1972 by Governor Cecil Andrus. It took effect on April 1, 1972. On March 22, 1972, the Idaho House voted was 49-15 in favor of House Bill 59, which restored a criminal code framework after the repeal of House Bill 161, which included reinstating common-law crimes and reintroduced the felony "crime against nature" law, which included a minimum five-year penalty with no maximum limit. The bill passed the Idaho Senate on February 1, 1972 and the vote was 34-1. It was signed on February 18, 1972 by Governor Cecil Andrus. It took effect on April 1, 1972.

At the time of the Lawrence decision in 2003, the penalty for violating a sodomy law varied widely from jurisdiction to jurisdiction among those states retaining their sodomy laws. The harshest penalties were in Idaho, where a person convicted of sodomy could earn a life sentence. Michigan followed, with a maximum penalty of 15 years' imprisonment while repeat offenders got life.[8] By 2002, 36 states had repealed their sodomy laws or their courts had overturned them. By the time of the 2003 Supreme Court decision, the laws in most states were no longer enforced or were enforced very selectively. The continued existence of these rarely enforced laws on the statute books, however, are often cited as justification for discrimination against gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals.

On June 26, 2003, the United States Supreme Court struck down in the Lawrence v. Texas decision the following jurisdictions (14 US states, 1 US territory and the Uniform Code of Military Justice) that statutes criminalized consensual sodomy: Alabama, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri (rest of the state outside of the Missouri Court of Appeals, Western District), North Carolina, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, United States Armed Forces, Utah and Virginia. On June 26, 2003, at the time of the Lawrence v. Texas decision, the following jurisdictions (20 US states, 1 US territory and the Uniform Code of Military Justice) had statutes criminalizing consensual sodomy: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, United States Armed Forces, Utah and Virginia.

Post Lawrence v. Texas

editIn 2005, Puerto Rico repealed its sodomy law, and in 2006, Missouri repealed its law against "homosexual conduct". In 2013, Montana removed "sexual contact or sexual intercourse between two persons of the same sex" from its definition of deviate sexual conduct, Virginia repealed its lewd and lascivious cohabitation statute, and sodomy was legalized in the US armed forces. In 2005, basing its decision on Lawrence, the Supreme Court of Virginia in Martin v. Ziherl invalidated § 18.2-344, the Virginia statute making fornication between unmarried persons a crime.[9]

On January 31, 2013, the Senate of Virginia passed a bill repealing § 18.2-345, the lewd and lascivious cohabitation statute enacted in 1877. On February 20, 2013, the Virginia House of Delegates passed the bill by a vote of 62 to 25 votes. On March 20, 2013, Governor Bob McDonnell signed the repeal of the lewd and lascivious cohabitation statute from the Code of Virginia.[10] On March 12, 2013, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit struck down § 18.2-361, the crimes against nature statute. On March 26, 2013, Attorney General of Virginia Ken Cuccinelli filed a petition to have the case reheard en banc, but the Court denied the request on April 10, 2013, with none of its 15 judges supporting the request.[11] On June 25, Cuccinelli filed a petition for certiorari asking the U.S. Supreme Court to review the Court of Appeals decision, which was rejected on October 7.[12][13]

On February 7, 2014, the Virginia Senate voted 40-0 in favor of revising the crimes against nature statute to remove the ban on same-sex sexual relationships. On March 6, 2014, the Virginia House of Delegates voted 100-0 in favor of the bill. On April 7, the Governor submitted a slightly different version of the bill. It was enacted by the legislature on April 23, 2014. The law took effect upon passage.[14] On February 26, 2019, the Utah legislature voted to eliminate the crime of sodomy between consenting adults.[15] Governor Gary Herbert signed the bill into law on March 26, 2019.[16][17]

On May 23, 2019, the Alabama House of Representatives passed, with 101 voting yea and 3 absent, Alabama Senate Bill 320, repealing the ban on "deviate sexual intercourse". On May 28, 2019, the Alabama State Senate passed Alabama Senate Bill 320, with 32 yea and 3 absent. The bill took effect on September 1, 2019.[18][19] Alabama is the southernmost continental state to repeal their sodomy law as of 2023.

On March 18, 2020, the Maryland legislature voted to repeal its sodomy law. The bill became law in May 2020 without the signature of Governor Larry Hogan.[20] While the original text of the bill intended to repeal both the state's sodomy law and unnatural or perverted sexual practice law, amendments from the Maryland Senate urged to solely repeal the sodomy law.[21] On March 31, 2023, the Maryland legislature voted to repeal the unnatural and perverted sexual practice law. The bill was sent to Governor Wes Moore for signature. As he did not veto the bill within 30 days of passage, Moore allowed for the bill to become law without his signature, and the repeal took effect on October 1, 2023.[22]

In March 2022, Idaho repealed its sodomy law.[23] The repeal was a result of a lawsuit brought on in September 2020 by a plaintiff known as John Doe. John Doe alleged his constitutional rights were violated when he was forced to register as a sex offender upon moving to Idaho due to a conviction for "oral sex" 2 decades prior.[24] On May 17, 2023, the Minnesota legislature passed an Omnibus Judiciary and Public Safety Bill that included provisions repealing the state's sodomy, adultery, fornication, and abortion laws. On May 19, Governor Tim Walz signed the bill into law. It took effect the following day.[25]

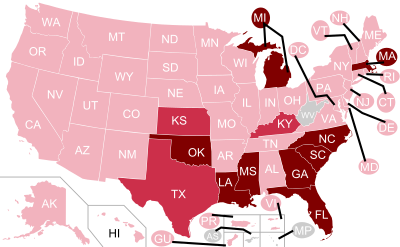

As of October 1, 2023, the following jurisdictions (12 US states) had statutes criminalizing consensual sodomy: Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Texas. These statutes penalties are not enforceable due to the binding precedent of Lawrence v. Texas, meaning consensual sodomy cannot be prosecuted.[26]

- Florida (Fld. Stat. 800.02.)

- Georgia (O.C.G.A. § 16-6-2)

- Kansas (Kan. Stat. 21-3505.)

- Kentucky (KY Rev Stat § 510.100.)

- Louisiana (R.S. 14:89.)

- Massachusetts (MGL Ch. 272, § 34.) (MGL Ch. 272, § 35.) – 2023 repeal bill

- Michigan (MCL § 750.158.) (MCL § 750.338.) (MCL § 750.338a.) (MCL § 750.338b.) – 2023 partial repeal bill

- Mississippi (Miss. Code § 97-29-59.)

- North Carolina (G.S. § 14-177.)

- Oklahoma (§21-886.)

- South Carolina (S.C. Code § 16-15-60.)

- Texas (Tx. Penal Code § 21.06.)

Sodomy laws by jurisdiction in the United States of America

editBelow is a table of sodomy laws in the jurisdictions in United States of America and penalties as applicable to the binding precedent of Lawrence v. Texas.[27][28] The most recent jurisdiction to repeal its sodomy ban is Maryland.

| Jurisdiction | Date statute struck down | Date statute repealed | Covered by statute | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bestiality | Opposite-sex intercourse | Same-sex intercourse | ||||||||||

| Anal sex | Married intercourse | Oral sex | Unmarried intercourse | Anal sex | Oral sex | |||||||

| Alabama | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

2019 | Ala. Code 1975 § 13A-6-220 - 221 | |||||||||

| Alaska | N/A | 1980 (sodomy) 1971 |

A.S. 11.61.140 | |||||||||

| American Samoa | 1979 | N/A | ||||||||||

| Arizona | 2001 | A.R.S. § 13-1411 | ||||||||||

| Arkansas | 2001 (Jegley v. Picado)[29] |

2005

1975 |

A.C.A. § 5-14-122 | |||||||||

| California | N/A | 1976 | Cal. Penal Code § 286.5 | |||||||||

| Colorado | 1972 | C. R. S. A. § 18-9-202 | ||||||||||

| Connecticut | 1971 | C. G. S. A. § 53a-73a | ||||||||||

| Delaware | 1973 | 11 Del.C. § 775 | ||||||||||

| District of Columbia | 1993 | D.C. Code § 22–1012.01. | ||||||||||

| Florida | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas; unnatural and lascivious act) 1971 |

1974 (crimes against nature) |

West's F. S. A. 828.126 | West's F. S. A. 800.02 | ||||||||

| Georgia | 1998 (Powell v. Georgia) |

N/A | O.C.G.A. § 16-6-6 | O.C.G.A. § 16-6-2 | ||||||||

| Guam | N/A | 1978 | 9 GCA § 70.40. | |||||||||

| Hawaii | 1973 | HRS § 711-1109.8 | ||||||||||

| Idaho | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

2022

1971 |

I.C. § 18-6602 | |||||||||

| Illinois | N/A | 1962 | 720 I.L.C.S. 5/12-35 | |||||||||

| Indiana | 1976 | I.C. 35-46-3-14 | ||||||||||

| Iowa | 1978 | I.C.A. § 717C.1 | ||||||||||

| Kansas | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

1969 (opposite-sex intercourse) |

K.S.A. 21-5504 | K.S.A. 21-5504 | ||||||||

| Kentucky | 1992 (Kentucky v. Wasson) |

1974 (opposite-sex intercourse) |

KRS § 525.137 | KRS § 510.100 | ||||||||

| Louisiana | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

N/A | LSA-R.S. 14:89.3 | LSA-R.S. 14:89 | ||||||||

| Maine | N/A | 1976 | 17 M.R.S.A. § 1031 | |||||||||

| Maryland | 1999 (Williams v. Glendening; anal sex) 1998 1990 |

2023 (unnatural and perverted sexual practice)[32] 2020 |

MD Code, Criminal Law, § 10-606. | |||||||||

| Massachusetts | 1974 (Commonwealth v. Balthazar)[34] |

N/A | M.G.L.A. 272 § 77

|

M.G.L.A. 272 § 34

| ||||||||

| Michigan | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) 1990 |

M.C.L.A. 750.158 | M.C.L.A. 750.158

| |||||||||

| Minnesota | 2001 (Doe v. Ventura) |

2023 | M.S.A. § 609.294 | |||||||||

| Mississippi | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

N/A | Miss. Code Ann. § 97-29-59 | |||||||||

| Missouri | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas; rest of the state outside of the Missouri Court of Appeals, Western District) 1999 |

2006 | V.A.M.S. 566.111 | |||||||||

| Montana | 1997 (Gryczan v. State)[37] |

2013 (same-sex intercourse)[38][39] 1974 |

MCA 45-8-218 | |||||||||

| Nebraska | N/A | 1978 | Neb. Rev. St. § 28-1010

| |||||||||

| Nevada | 1993 | N. R. S. 201.455 | ||||||||||

| New Hampshire | 1975 | N.H. Rev. Stat. § 644:8g | ||||||||||

| New Jersey | 1978 | N. J. S. A. 4:22-17 | ||||||||||

| New Mexico | 1975 | NMSA § 30-9A-3 | ||||||||||

| New York | 1980 (New York v. Onofre; excluded the New York National Guard) |

2000 | McKinney's Penal Law § 130.20 | |||||||||

| North Carolina | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

N/A | N.C.G.S.A. § 14-177 | |||||||||

| Northern Mariana Islands | N/A | 1983 | N/A | |||||||||

| North Dakota | 1973 | NDCC, § 12.1-20-12 | ||||||||||

| Ohio | 1974 | R.C. § 959.21 | ||||||||||

| Oklahoma | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas; same-sex intercourse) 1988 |

N/A | 21 Okl. St. Ann. § 886 | |||||||||

| Oregon | N/A | 1972 | O. R. S. § 167.333 | |||||||||

| Pennsylvania | 1980 (Commonwealth v. Bonadio)[40] |

1995 (unmarried opposite-sex intercourse and same-sex intercourse) 1972 |

18 Pa.C.S.A. § 3129 | |||||||||

| Puerto Rico | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

2006 (opposite-sex anal sex and same-sex anal and oral sex) 1974 |

P.R. Laws tit. 33, § 4773 | |||||||||

| Rhode Island | N/A | 1998 | Gen.Laws 1956, § 11-10-1 | |||||||||

| South Carolina | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

N/A | Code 1976 § 16-15-120 | Code 1976 § 16-15-120 | ||||||||

| South Dakota | N/A | 1977 | SDCL § 22-22-42 | |||||||||

| Tennessee | 1996 (Campbell v. Sundquist) |

1996 (same-sex intercourse)[41] 1989 |

T. C. A. § 39-14-214 | |||||||||

| Texas | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) 1970 |

1974 (opposite-sex anal and oral sex[43]) |

V. T. C. A., Penal Code § 21.09 | V. T. C. A., Penal Code § 21.06 | ||||||||

| United States Armed Forces | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

2013 (sodomy) |

10 U.S. Code § 934 - Art. 134. | |||||||||

| United States of America | N/A | |||||||||||

| Utah | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

2019

1971 |

U.C.A. 1953 § 76-9-301.8 | |||||||||

| Vermont | N/A | 1977 | 13 V.S.A. § 352 | |||||||||

| Virgin Islands of the United States | 1985 | 14 V.I.C. § 2062 | ||||||||||

| Virginia | 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

2014 (anal and oral sex)[44] 2013 |

Va. Code Ann. § 18.2-361 | |||||||||

| Washington | N/A | 1976 | West's RCWA 16.52.205 | |||||||||

| West Virginia | 1976 | N/A | ||||||||||

| Wisconsin | 1983 | W.S.A. 944.18 | ||||||||||

| Wyoming | 1977 | W.S.1977 § 6-4-601 | ||||||||||

Federal law

editSodomy laws in the United States were largely a matter of state rather than federal jurisdiction, except for laws governing the District of Columbia and the U.S. Armed Forces.

District of Columbia

editIn 1801, the 6th United States Congress enacted the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, a law that continued all criminal laws of Maryland and Virginia, with those of Maryland applying to the portion of the District ceded from Maryland and those of Virginia applying to the portion ceded from Virginia. As a result, in the Maryland-ceded portion, sodomy was punishable with up to seven years' imprisonment for free persons and with the death penalty for enslaved persons, whereas in the Virginia-ceded portion it was punishable between one and ten years' imprisonment for free persons and with the death penalty for enslaved persons. Maryland repealed the death penalty for slaves in 1809 and modified the penalty for all persons to match Virginia's terms of imprisonment. In 1847, the Virginia-ceded portion was given back to Virginia, thus only the Maryland law had effect in the district.[45] In 1871, Congress enacted the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871, a law that reorganized the district government and granted it home rule. All existing laws were retained unless and until expressly altered by the new city council. Direct rule was reinstated in 1874. The criminal status of sodomy became ambiguous until 1901, when Congress passed legislation recognizing common law crimes, punishable with up to five years' imprisonment or a fine of $1,000.[45]

In 1935, Congress made it a crime in the district to solicit a person "for the purpose of prostitution, or any other immoral or lewd purpose". In 1948, Congress enacted the first law specific to sodomy in the district, which established a penalty of up to ten years in prison or a fine of up to $1,000, regardless of sexuality. Oral sex was included in the law's application. Also included with this law was a psychopathic offender law and a law "to provide for the treatment of sexual psychopaths".[45] The metropolitan police department eventually had several officers whose sole job was to "check on homosexuals". Multiple court cases dealt with the issue in the following years. Many of the published sodomy and solicitation cases during the 1950s and 1960s reveal clear entrapment policies by the local police, some of which were disallowed by reviewing courts. In 1972, settling the case of Schaefers et al. v. Wilson, the D.C. government announced its intention not to prosecute anyone for private, consensual adult sodomy, an action disputed by the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia. The action came as part of a stipulation agreement in a court challenge to the sodomy law brought by four gay men.[45]

In 1973, Congress again granted the district home rule through the District of Columbia Home Rule Act. It provided for a new city council that could pass its own laws. However laws regarding certain topics, such as changes to the criminal code, were restricted until 1977. All laws passed by the D.C. government are subject to a mandatory 30-day "congressional review" by Congress. If they are not blocked, then they become law.[46] In 1981, the D.C. government enacted a law that repealed the sodomy law, as well as other consensual acts, and made the sexual assault laws gender neutral. However, the Congress overturned the new law.[47] A successful legislative repeal of the law followed in 1993. This time, Congress did not interfere.[48][45] In 1995, all references to sodomy were completely removed from the criminal code, and in 2004, the D.C. government repealed an outdated law against fornication.[49]

Military

editAlthough the U.S. military discharged soldiers for homosexual acts throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century, U.S. military law did not expressly prohibit homosexuality or homosexual conduct until February 4, 1921.[50]

On March 1, 1917, the Articles of War of 1916 were implemented. This included a revision of the Articles of War of 1806, the new regulations detail statutes governing U.S. military discipline and justice. Under the category Miscellaneous Crimes and Offences, Article 93 states that any person subject to military law who commits "assault with intent to commit sodomy" shall be punished as a court-martial may direct.[51]

On June 4, 1920, Congress modified Article 93 of the Articles of War of 1916. It was changed to make the act of sodomy itself a crime, separate from the offense of assault with intent to commit sodomy.[51] It went into effect on February 4, 1921.[52]

On May 5, 1950, the Uniform Code of Military Justice was passed by Congress and was signed into law by President Harry S. Truman, and became effective on May 31, 1951. Article 125 forbids sodomy among all military personnel, defining it as "any person subject to this chapter who engages in unnatural carnal copulation with another person of the same or opposite sex or with an animal is guilty of sodomy. Penetration, however slight, is sufficient to complete the offence."[51]

As for the U.S. Armed Forces, the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces has ruled that the Lawrence v. Texas decision applies to Article 125, severely narrowing the previous ban on sodomy. In both United States v. Stirewalt and United States v. Marcum, the court ruled that the "conduct [consensual sodomy] falls within the liberty interest identified by the Supreme Court,"[53] but went on to say that despite the application of Lawrence to the military, Article 125 can still be upheld in cases where there are "factors unique to the military environment" that would place the conduct "outside any protected liberty interest recognized in Lawrence."[54] Examples of such factors include rape, fraternization, public sexual behavior, or any other factors that would adversely affect good order and discipline. Convictions for consensual sodomy have been overturned in military courts under Lawrence in both United States v. Meno[55] and United States v. Bullock.[56]

Repeal

editOn December 26, 2013, President Barack Obama signed into law the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014, which repealed the Article 125 ban on consensual sodomy.[57]

References

edit- ^ Eskridge, William N. (2009). Gaylaw: Challenging the Apartheid of the Closet. Harvard University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780674036581.

- ^ Colin L. Talley, "Gender and male same-sex erotic behavior in British North America in the seventeenth century." Journal of the History of Sexuality (1996): 385-408. online

- ^ William E Benemann, Male-Male Intimacy in Early America: Beyond Romantic Friendships (2006).

- ^ "Amendment VIII: Thomas Jefferson, A Bill for Proportioning Crimes and Punishments". Press-pubs.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-02-04. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ^ Patricia S. Ticer. "Virginia". Glapn.org. Archived from the original on 2011-10-04. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- ^ Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003).

- ^ Canaday, Margot (September 3, 2008). "We Colonials: Sodomy Laws in America". The Nation. Archived from the original on January 26, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ "Section 750.158 - Crime against nature or sodomy; penalty, Mich. Comp. Laws § 750.158 | Casetext Search + Citator". casetext.com.

- ^ Google Scholar: Martin v.Ziherl, accessed April 9, 2011

- ^ "SB 969". Open:States. 20 February 2013. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ "Ken Cuccinelli Loses Petition To Uphold Anti-Sodomy Law". The Huffington Post. 10 April 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-04-13. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- ^ "Ken Cuccinelli Appeals To Defend Virginia's Anti-Sodomy Law At Supreme Court". Huffington Post. June 25, 2013. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013.

- ^ "Court won't hear Va. appeal over sodomy law". USA Today. October 7, 2013. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017.

- ^ "LIS > Bill Tracking > SB14 > 2014 session". Leg1.state.va.us. Archived from the original on 2014-03-10. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ "Adultery and sodomy among consenting adults closer to being legal in Utah". 26 February 2019.

- ^ Bennett, Craig (March 26, 2019). "Governor Signs Bill Making Adultery and Sodomy Legal Between Consenting Adults". News Talk KDXU.

- ^ "Adultery and sodomy among consenting adults are no longer illegal in Utah". 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Act 2019-465, SB320" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-06-30.

- ^ AL SB 320

- ^ "Maryland Legislation HB0081". mgaleg.maryland.gov.

- ^ "Maryland HB81 | 2020 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "Bill to repeal Md. sodomy law to take effect without governor's signature". The Washington Blade. May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ "Idaho S1325 | 2022 | Regular Session".

- ^ Boone, Rebecca (September 24, 2020). "Idaho man sues over state's anti-sodomy law". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 23, 2021.

- ^ "SF 2909 Status in the Senate for the 93rd Legislature (2023 - 2024)". www.revisor.mn.gov. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ Sulzberger, A.G. (21 Jan 2012), "Kansas Law on Sodomy Stays on Books Despite a Cull", The New York Times, nytimes.com, archived from the original on January 22, 2012, retrieved 21 Jan 2012

- ^ "United States Sodomy Laws". Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ GLAPN - Case Law: "Case law". Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "Jegley v. Picado 80 S.W.3d 332". Apa.org. Archived from the original on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ^ "800.02 Unnatural and lascivious act. A person who commits any unnatural and lascivious act with another person commits a misdemeanor of the second degree". Archive.flsenate.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- ^ Google Scholar: Stephen Adam Schochet v. State of Maryland, October 9, 1990, accessed March 11, 2011

- ^ "Legislation - SB0054". mgaleg.maryland.gov.

- ^ "Maryland HB81 | 2020 | Regular Session".

- ^ Massachusetts Cases: Commonwealth v. Richard L. Balthazar, 366 Mass. 298 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 11, 2011

- ^ Michigan Organization for Human Rights v. Kelley, No. 88–815820 CZ slip op. (Mich. 3rd Cir. Ct. July 9, 1990).

- ^ Gay Times: Michigan Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Montana Kills Sodomy Law". Thetaskforce.org. 1997-07-04. Archived from the original on 2011-08-04. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- ^ "Montana governor signs bill to strike down obsolete sodomy law – LGBTQ Nation". Lgbtqnation.com. 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-10-25. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ "LAWS Detailed Bill Information Page". Laws.leg.mt.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-10-22. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Appellant, v. Michael BONADIO, Patrick Gagliano, Shane Wimbel, and Dawn Delight a/k/a Mildred I. Kannitz, Appellees

- ^ Gonzalez, Tony (November 14, 2016). "Nashville Man Cleared Of 1995 'Homosexual Acts' Conviction, But Cases Linger For 41 Others". wpln.org.

- ^ "The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States - Tennessee". Glapn.org. Archived from the original on 2013-04-24. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ "The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States - Texas". Glapn.org. Archived from the original on 2011-10-04. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- ^ Weiner, Rachel (6 March 2014). "Virginia lawmakers repeal sodomy ban". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Painter, George (2005-01-31). "The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States - District of Columbia". Gay and Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ "Chronology of the District of Columbia's Denial of Democracy". D.C. Vote. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ "H.Res.208 - A resolution disapproving the action of the District of Columbia Council in approving the District of Columbia Sexual Assault Reform Act of 1981". Congress.gov. United States Congress. Archived from the original on 2021-06-18. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ Sanchez, Rene (1993-04-08). "D.C. Repeals Sodomy Law". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ^ "D.C. Sodomy Law". Human Rights Campaign. 2007-03-08. Archived from the original on 2016-11-15. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

- ^ "United States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Key Dates in US Policy on Gay Men and Women in the United States Military". usni.org. Archived from the original on 2014-03-23. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- ^ "HyperWar: The Articles of War, Approved June 4, 1920". October 4, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-10-04.

- ^ U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces: U.S. v. Stirewalt, September 29, 2004 Archived May 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, accessed August 16, 2010

- ^ U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces: U.S. v. Marcum, August 23, 2004 Archived April 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, accessed August 16, 2010

- ^ United States v. Webster M. Smith, USCG CMG0224 (United States Coast Guard Court of Criminal Appeals 2008), archived from the original on 2012-09-25.

- ^ United States v. Bullock, Army 20030534 (United States Army Court of Criminal Appeals 2004), archived from the original on 2017-02-02.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (December 20, 2013). "Defense bill contains gay-related provisions". Washington Blade. Archived from the original on December 22, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

Further reading

edit- Ellen Ann Andersen, Out of the Closets and Into the Courts: Legal Opportunity Structure and Gay Rights Litigation (University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0-472-11397-6, Ch. 4 "Sodomy Reform from Stonewall to Bowers," Ch. 5 "Sodomy Reform from Bowers to Lawrence", accessed June 2, 2022

- Carlos A. Ball, From the Closet to the Courtroom: Five LGBT Rights Lawsuits that have Changed our Nation (Beacon Press, 2010), accessed June 2, 2022 ISBN 0-8070-0078-7

- Patricia A. Cain, Rainbow Rights: The Role of Lawyers and Courts in the Lesbian and Gay Civil Rights Movement (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2000), ISBN 0-8133-2618-4, Ch. 4 "Private Rights: 1950-1985", accessed June 2, 2022

- William N. Eskridge, Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861-2003 (NY: Viking, 2008), ISBN 0-670-01862-7

- Leslie Moran, The Homosexual(ity) of Law (NY: Routledge, 1996)

- Martha C. Nussbaum, From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and Constitutional Law (NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), ISBN 0-19-530531-0

- Jason Pierceson, Courts, Liberalism, and Rights: Gay Law and Politics in the United States and Canada (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), accessed June 2, 2022

- Daniel R. Pinello, Gay Rights and American Law (Cambridge University Press, 2003), accessed August 26, 2010

- Jerald Sharum "Controlling Conduct: The Emerging Protection of Sodomy in the Military" in Albany Law Review, vol. 69, No. 4, 2006