Sophiatown /soʊˈfaɪətaʊn/, also known as Sof'town or Kofifi, is a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa. Sophiatown was a poor multi-racial area and a black cultural hub that was destroyed under apartheid. It produced some of South Africa's most famous writers, musicians, politicians and artists, like Father Huddleston, Can Themba, Bloke Modisane, Es'kia Mphahlele, Arthur Maimane, Todd Matshikiza, Nat Nakasa, Casey Motsisi, Dugmore Boetie, and Lewis Nkosi.

Sophiatown

Sof'town, Kofifi, Triomf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 26°10′36″S 27°58′54″E / 26.1767°S 27.9816°E | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | Gauteng |

| Municipality | City of Johannesburg |

| Main Place | Johannesburg |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.95 km2 (0.37 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

• Total | 5,371 |

| • Density | 5,700/km2 (15,000/sq mi) |

| Racial makeup (2011) | |

| • Black African | 26.8% |

| • Coloured | 25.8% |

| • Indian/Asian | 5.1% |

| • White | 41.4% |

| • Other | 0.8% |

| First languages (2011) | |

| • Afrikaans | 44.5% |

| • English | 31.9% |

| • Tswana | 4.7% |

| • Zulu | 4.5% |

| • Other | 14.4% |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (SAST) |

| Postal code (street) | 2092 |

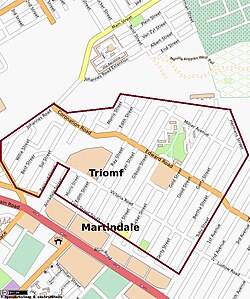

Rebuilt as a whites-only area under the name of Triomf ("Triumph") in the 1960s, in 2006 it was officially returned to its original name. Sophiatown was one of the oldest black areas in Johannesburg and its destruction represented some of the excesses of South Africa under apartheid.[2]

History

editSophiatown was originally part of the Waterfall farm. Over time it included the neighbouring areas of Martindale and Newclare. It was purchased by a speculator, Hermann Tobiansky, in 1897. He acquired 237 acres four miles or so west of the centre of Johannesburg.[3] The private leasehold township was surveyed in 1903 and divided into almost 1700 small stands. The township was named after Tobiansky's wife, Sophia, and some of the streets were named after his children Toby, Gerty, Bertha and Victoria.[4] Before the enactment of the Natives Land Act, 1913, black South Africans also had freehold rights in the area, and bought properties in the suburb. The distance from the city centre was seen as disadvantageous, and after the City of Johannesburg built a sewage plant nearby, the area seemed even less attractive.[5] Most of the wealthy people had moved out by 1920. By the late 1940s Sophiatown had a population of nearly 54,000 Africans, 3,000 Coloureds, 1,500 Indians and 686 Chinese, both owners and renters.[4] As the land never belonged to the Johannesburg municipality, it was never developed through municipal housing schemes, which in black areas usually involved row upon row of "matchbox" houses, based on uniformity and lack of character.[13]

Forced removals

editIt was adjacent to white working-class areas, such as Westdene and Newlands, and known for high levels of crime and poverty. The seregationist state viewed it as a slum, and believed that it was too close to white areas. From 1944, i.e., even before apartheid, the Johannesburg City Council planned to move the non-white population out of the Western Areas of Johannesburg, including Sophiatown. After the election victory of the National Party in 1948, relocation plans were debated at the level of national politics.[4] Under the Group Areas Act and the Immorality Amendment Act, both of 1950, as well as the Natives Resettlement Act of 1954, the national state was empowered to stop people of different races residing together. This allowed systematic urban segregation and the destruction of mixed areas .[6]

When the Sophiatown removals scheme was promulgated, Sophiatown residents united to protest against the forced removals, creating the slogan "Ons dak nie, ons phola hier" (roughly, "we won't move"). Figures like Nelson Mandela were key to the resistance. Some whites, like Father Trevor Huddleston, Helen Joseph and Ruth First also played an important role.[7] On 9 February 1955, 2,000 policemen, armed with handguns, rifles, and clubs known as knobkierries, forcefully moved the first batch of black families from Sophiatown to Meadowlands, Soweto. In the years that followed, other blacks were removed, and the Coloured evicted to Eldorado Park outside of Johannesburg, in addition to Westbury, Noorgesig and other coloured townships; the Indians were moved to Lenasia; and the Chinese moved to central Johannesburg.[6] Over eight years Sophiatown was flattened and removed from the maps of Johannesburg.[7]

Triomf

editAfter the forced removals and demolition, the area was rebuilt as renamed "Triomf" —Afrikaans for Triumph—by the government.[8] The social engineers of apartheid tried to create a suburb for the white working-class, and Triomf was predominantly populated by poorer working-class Afrikaners.[9] Marlene van Niekerk's award-winning novel Triomf focuses on the daily lives of a family of poor whites in this era.[9]

Restoration of the name Sophiatown

editThe Johannesburg City Council took the decision in 1997 to reinstate the old name Sophiatown for the suburb. On 11 February 2006, the process finally came to fruition when Mayor Amos Masondo changed the name of Triomf back to Sophiatown.[10] Today, Sophiatown again has a racially mixed population.

Geography and geology

editSophiatown is located on one of Johannesburg's ridges called Melville Koppies. Melville Koppies lies on the Kaapvaal craton, which dates from three billion years ago. The Koppies lie at the base of lithified sediments in the form of conglomerate, quartzite, shale, and siltstone. It represents the first sea shores and shallow beds of an ancient sea. It also forms part of the lowest level of one of the world's most well known geological features, the Witwatersrand Supergroup. Several fairly narrow layers of gravel, deposited quite late in the sequence, and bearing heavy elements, made the Witwatersrand Supergroup famous. These are the gold-bearing conglomerates of the main reefs. Melville Koppies represents in microcosm most of the features of the Witwatersrand Supergroup. What it does not have is gold-bearing rock. The gold occurs millions of years later, and several kilometres higher up, in the sequence.[11] In the last 1,000 years, black Iron Age immigrants arrived and remains of their kraal walls can be found in the area.[12]

The Melville Koppies Nature Reserve is a Johannesburg City Heritage Site.

Culture

editEarly life in Sophiatown

editSophiatown, unlike other townships in South Africa, was a freehold township, which meant that it was one of the rare places in South African urban areas where blacks were allowed to own land. This was land that never belonged to the Johannesburg municipality, and so it never developed through municipal housing schemes.[13] The houses were built according to people's ability to pay, tastes, and cultural background. Some houses were built of brick and had four or more rooms; some were much smaller. Others were built like homes in the rural areas; others still were single room shacks put together with corrugated iron and scrap sheet metal. The majority of the families living in Sophiatown were tenants and sub-tenants. Eight or nine people lived in a single room and the houses hid backyards full of shanties built of cardboard and flattened kerosene cans,[14] since many Black property owners in Sophiatown were poor. In order to pay back the mortgages on their properties, they had to take in paying tenants.[13]

Sophiatown residents had a determination to construct a respectable lifestyle in the shadow of a state that was actively hostile to such ambitions. A respectable lifestyle rested on the three pillars of religious devotion, reverence for formal education, and a desire for law and order.[15]

People struggled to survive together starvation was a serious problem, and a rich culture based on shebeens (informal and mostly illegal pubs), mbaqanga music, and beer-brewing developed. The shebeens were one of the main forms of entertainment. People came to the shebeens not only for skokiaan or baberton (illegally self-made alcoholic beverages), but to talk about their daily worries, their political ideas and their fears and hopes. In these shebeens the politicians tried to influence others and get them to conform to their form of thinking. If one disagreed he immediately became suspect and was classified as a police informer.[16]

These two conflicting images of Sophiatown stand side by side – the romantic vision of a unique community juxtaposed with a seedy and violent township with dangers lurking at every corner.[13]

Arts and literature

editThe cultural process was somehow intensified in Sophiatown, as in Soho, the Greenwich Village, the Quartier Latin or Kreuzberg. It was akin to what Harlem was to New York in the 1920s Harlem Renaissance[3] and is sometimes referred to as the Sophiatown renaissance.

The musical King Kong, sponsored by the Union of South African Artists, is described as the ultimate achievement and final flowering of Sophiatown multi-racial cultural exploits in the 1950s. King Kong is based on the life of Sophiatown legend Ezekiel Dlamini, who gained popularity as a famous boxer, notorious extrovert, a bum, and a brawler.[17] The King Kong musical depicted the street life, the illicit shebeens, the violence, and something approximating the music of the township: jazz, penny whistles and the work songs of the black miners. When King Kong premiered in Johannesburg, Miriam Makeba the vocalist of the Manhattan Brothers, played in the female lead role. The musical later went to London's West End for two years.[3]

One of the boys, Hugh Masekela at St Peter's School, told Father Huddleston of his discovery of the music of Louis Armstrong. Huddleston found a trumpet for him and as the interest in making music caught on among the other boys, the Huddleston Jazz Band was formed. Masekela did not stay very long in Sophiatown. He was in the orchestra of King Kong and then made his own international reputation.[16]

Images of Sophiatown were initially built up in literature by a generation of South African writers: Can Themba, Bloke Modisane, Es'kia Mphahlele, Arthur Maimane, Todd Matshikiza, Nat Nakasa, Casey Motsisi, Dugmore Boetie, and Lewis Nkosi who all lived in Sophiatown at various stages during the 1950s. They all shared certain elements of a common experience: education at St Peter's School and Fort Hare University, living in Sophiatown, working for Drum magazine, exile, banning under the Suppression of Communism Act and for many the writing of an autobiography.[18]

Later, images of Sophiatown could be found in Nadine Gordimer's novels, Miriam Makeba's ghostwritten autobiography and Trevor Huddleston's Naught for your comfort.[19] Alan Paton also details the social, cultural and political trajectory of Sophiatown in his 1983 novel, Ah, but Your Land Is Beautiful.[20]

Marlene van Niekerk's novel Triomf focuses on the suburb Triomf and recounts the daily lives of a family of poor white Afrikaners.[9] The book has been turned into a movie called Triomf, which won the Best South African Movie award in 2008.[21]

Crime and gangsterism

editCrime and violence were a reality of urban life and culture in Sophiatown. The poverty, misery, violence and lawlessness of the city led to the growth of many gangs. Sections of society frowned on gangsterism as anti-social behaviour and gangsters like Kortboy and Don Mattera were despised by many as "anti social", but were also sometimes perceived as “social bandits” that were part of the resistance to apartheid.[22]

After the Second World War, there was a large increase in the number of gangs in Sophiatown. Part of the reason for this was that there were about 20,000 African teenagers in the city who were not at school and did not have jobs. Township youths were unable to find jobs easily. Employers were reluctant to employ teenagers as they did not have any work experience, and many of them were not able to read or write. They also considered them to be undisciplined and weak.[22]

In Johannesburg in the 1950s, crime was a day-to-day reality, and Sophiatown was the nucleus of all reef crimes. Gangsters were city-bred and spoke a mixture of Afrikaans and English, known as tsotsitaal. Some of the more well-known gangs in Sophiatown were the Russians, the Americans, the Gestapo, the Berliners and the Vultures. The names the Gestapo and the Berliners reflect their admiration for Hitler, whom they saw as some kind of hero, for taking on the whites of Europe.[22] The best known gang from this period, and also best studied, was the Russians. They were a group of Basotho migrant workers who banded together in the absence of any effective law enforcement by either mine owners or the state. The primary goal of this gang was to protect members from the tsotsis and from other gangs of migrant workers, and to acquire and defend resources they found desirable - most notably women, jobs and the urban space necessary for the parties and staged fights that formed the bulk of their weekend entertainment.[23]

One of the more successful community campaigns emerged in the early 1950s when informal policing initiatives known as the Civic Guards were mobilized to combat rising crime. This attempt to restore law and order attracted widespread support prior to a series of bloody clashes with the migrant criminal society from the poorer enclave of Newclare. This provided the state with an excuse to ban the Guard groups which they eyed with suspicion because of their ANC and Communist Party connections. These supposed arbiters of law and order engaged in a series of brutal street battles with members of the "Russians" gang in the early 1950s.[24]

The representation of gangsters in the literature (Drum magazine) went through very different stages during the 1950s and early 1960s. The first representation is characterized by consistent condemnations of crime as an urban phenomenon that threatens the rural identity of tribal blacks. The second is almost a complete turn-around from the first, as gangsters are portrayed as urban survivors who are able to achieve a standard of living normally denied to blacks. The final period is an extended period of nostalgia for the shebeen culture that all but disappeared with the destruction of Sophiatown.[25]

Landmarks

editThe Church of Christ the King

editOne of the few tangible reminders of the old Sophiatown is the Anglican Church of Christ the King in Ray Street. The architect was Frank Flemming, who designed 85 churches throughout South Africa.[26] The church was constructed in 1933. The bell tower was added in 1936. So little money was made available for the construction that the architect called it a "Holy Barn".[27] The church's distinctive feature was a mural that is no longer visible. It was painted between 1939 and 1941 by Sister Margaret.[26] The church was an icon of the liberation struggle in South Africa. In 1940 Trevor Huddleston was appointed Rector. He was an outspoken opponent of apartheid. In 1955 during the forced removals, Huddleston was recalled to England. His ashes reside next to his former church. On the north-eastern side of the church there is a mural depicting Huddleston walking the dusty streets of Sophiatown. This mural was painted by 12 apprentice students under patronage of the Gerard Sekoto Foundation. It shows two children tugging at his cassock as well as Sekoto's famous yellow houses.[28] The entire Sophiatown community was removed by the end of 1963; the church was deconsecrated in 1964 and sold to the Department of Community Development in 1967. In the 1970s it was bought by the Nederduitsch Hervormde Kerk, which used it for Sunday School. The church changed hands again and the Pinkster Protestantse Kerk bought the building and altered it significantly. The nave was enclosed, a large font was built and wooden panelling and false organ pipes changed the look of the interior. In 1997 the Anglicans bought the church back and it was reconsecrated; the changes were reversed and the building was largely restored to its former self. However, the hall and gallery the Pinkster Protestantse Kerk had built were retained.[29]

Dr A. B. Xuma's house

editDr A. B. Xuma was a medical doctor who had trained in the United States and the United Kingdom. He was a local celebrity, President of the African National Congress and Chairperson of the Western Areas Anti-Expropriation and Proper Housing Committee. His house was a landmark in Sophiatown (73 Toby Street) and was declared a National Heritage Monument on 11 February 2006. Currently, the house is the location of the Sophiatown Heritage and Cultural Centre.[30] This is one of two houses to escape the destruction of Sophiatown by the government in the late 1950s. It was built in 1935 and named Empilweni. Xuma and his second wife Madie Hall Xuma lived there until 1959.[27] The writer, actor and journalist Bloke Modisane reminisces that among all those modest, run-down buildings, could stand the palatial home of Dr A. B. Xuma with its two garages. Modisane remembers how he and his widowed mother, who ran a shebeen, had looked to Xuma and his house for a model of the good life, i.e. separate bedrooms, a room for sitting, another for eating, and a room to be alone, for reading or thinking, to shut out South Africa and not be black.[31]

Good Street

editGood Street was significant in the life of Sophiatown. It was described as a "Street of Shebeens". The writer Can Themba's house, called the House of Truth, was on Good Street, as well as Fatty Phyllis Peterson's 39 Steps. To get to the 39 Steps, one had to walk up a flight of steps, which looked by all accounts very dingy. One was then met by Fatty, who sold about every type of drink: whisky, brandy, gin, beer, wine, etc. Sometimes she even supplied cigars.[32] Good Street was also renowned for its Indian, Chinese and Jewish shops, and for being a street of criminals and gangsters.[30]

St Joseph's Home for Children

editThe Home opened its doors in 1923. It was built as a diocesan memorial to the Coloured men who paid the ultimate sacrifice for their country. It was run by the Anglican nuns, the Order of St Margaret, East Grinstead, who remained in charge until 1978, when they left South Africa in protest against apartheid. The Main Block, Boys' House and Priests' House were designed by the diocesan architect F. L. H. Flemming. The Church successfully opposed removal of the Home because the property was on farm land and not part of a proclaimed township.[27]

The Odin Cinema

editThere were two cinemas in Sophiatown. The larger was the Odin, which at the time was also the largest in Africa and could seat 1,200 people. The other cinema, Balansky's, was a lower-class, rougher movie-house, while the Odin Cinema was more up-market. The Odin was the pride of Sophiatown. It was owned by a white couple, the Egnoses, who were known as Mr and Mrs Odin. Not only did they provide much loved entertainment, but also made the Odin available for political meetings, parties and stage performances. Some international acts played to multi-racial audiences at the Odin.[33] It was also the site of a series of "Jazz at the Odin" jam sessions featuring white and black musicians. Also at a meeting at the Odin, the ultimately unsuccessful resistance to the destruction of Sophiatown began to coalesce.[16]

Freedom Square

editFreedom Square was located on the corner of Victoria and Morris Streets. It was famous in the 1950s for the political meetings held there. It was utilised by the African National Congress (ANC) and the Transvaal Congress Party. Many of the meetings were chaired by Trevor Huddleston. Freedom Square facilitated the cooperation between the aforementioned political parties. Here parties worked together against the apartheid regime.[30] Freedom Square in Sophiatown should not be confused with Freedom Square in Kliptown, Soweto, where the Freedom Charter was adopted by the ANC in 1955. It was in this Freedom Square in Sophiatown that Nelson Mandela made his first public allusion to violence and armed resistance as a legitimate tool for change. This earned him a reprimand from Albert Luthuli who by then replaced Dr A.B. Xuma as president of the ANC.[34] Current remnants of Freedom Square may be found beneath a school playing field alongside the Christ the King Church.[35]

St Cyprian's Missions School

editThis primary school was the site of religious and educational significance in Sophiatown. It was an Anglican Mission school located in Meyer Street and was established in 1928. St Cyprian's was the largest primary school in Sophiatown.[30] Oliver Tambo and Trevor Huddleston taught here, as both were passionate about education.[36] It was also the St Cyprian's School boys who a dug out the pool behind the house of the Community of the Resurrection in order to have a swimming pool. The school boys of St Cyprian's later went to Father Ross or Father Raynes or Father Huddleston who tried to get them bursaries to go to St Peter's School, then Fort Hare University and later even the University of the Witwatersrand. The idea was that they should come back as doctors.[37]

Oak tree in Bertha Street

editThe tree gained a sinister reputation as the "Hanging Tree" when two people hanged themselves from its branches, both due to being subjected to the forced removals.[30] The tree was designated as of the first Champion Tree of South Africa. Champion trees are trees in South Africa that are of exceptional importance, and deserve national protection.[38]

Notable residents

editSee also

edit- Sophiatown, a 2003 film about Sophiatown

- Drum, a 2004 film about Sophiatown

- Come Back, Africa, a film shot underground in Sophiatown in the 1950s by Lionel Rogosin with writing credits by Bloke Modisane, Lewis Nkosi, and Lionel Rogosin.

- "The Suit", a short story by Sophiatown-resident Can Themba, set in 1950s Sophiatown.

- The Suit (2016 film), a short film adaptation of the Can Themba short story set in Sophiatown, written and directed by Jarryd Coetsee.

References

edit- ^ a b c d "Sub Place Sophiatown". Census 2011.

- ^ Otzen, Ellen (11 February 2015). "The town destroyed to stop black and white people mixing". BBC News. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Hannerz, Ulf (June 1994). "Sophiatown: The view from afar". Journal of Southern African Studies. 20 (2): 184. doi:10.1080/03057079408708395.

- ^ a b c Brink, Elzabe (2010). University of Johannesburg: The University for a new Generation. Johannesburg: Division of Institutional Advancement, University of Johannesburg. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-86970-689-3.

- ^ Hannerz, Ulf (June 1994). "Sophiatown: The view from afar". Journal of Southern African Studies. 20 (2): 185. doi:10.1080/03057079408708395.

- ^ a b "1955 Sophiatown Forced Removals". National Digital Repository. National Digital Repository. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ a b Sindane, Lucky; Davie, Lucille (9 February 2005). "Remembering Sophiatown". Joburg.org.za. City of Johannesburg. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Giliomee, Herman (2003). The Afrikaners. Cape Town: Tafelberg. p. 507. ISBN 0-624-03884-X.

- ^ a b c Viljoen, Louise (Winter 1996). "Postcolonialism and recent woman's writing in Afrikaans" (PDF). World Literature Today. 70 (1): 63–72. doi:10.2307/40151854. JSTOR 40151854. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ Davie, Lucille (14 February 2006). "Sophiatown again, 50 years on". City of Johannesburg. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Melville Koppies Geology". Friends of Melville Koppies. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Melville Koppies". Friends of Melville Koppies. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ a b c "Life in Sophiatown". South African History Online. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Martin, Peter Bird (26 November 1955). "Cities of the World No. 14: Johannesburg". The Saturday Evening Post.

- ^ Kynoch, Gary (2005). "Book Review of: Respectability and Resistance: A History of Sophiatown by David Goodhew". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 38 (1). Boston University African Studies Center: 135. JSTOR 40036478.

- ^ a b c Hannerz, Ulf (June 1994). "Sophiatown: The view from afar". Journal of Southern African Studies. 20 (2): 187. doi:10.1080/03057079408708395.

- ^ Gready, Paul (March 1990). "The Sophiatown writers of the fifties: The unreal reality of their world". Journal of Southern African Studies. 16 (1): 9. doi:10.1080/03057079008708227.

- ^ Gready, Paul (March 1990). "The Sophiatown writers of the fifties: The unreal reality of their world". Journal of Southern African Studies. 16 (1): 4. doi:10.1080/03057079008708227.

- ^ Hannerz, Ulf (June 1994). "Sophiatown: The view from afar". Journal of Southern African Studies. 20 (2): 181. doi:10.1080/03057079408708395.

- ^ Paton, Alan. Ah, but Your Land is Beautiful. Penguin Books. 1983. pp. 111-116.

- ^ Raeburn, Michael. "Triomf". Archived from the original on 7 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ a b c "Gangsterism in Sophiatown". South African History Online. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ Fenwick, Mac (1996). "'Tough guy, eh?': The gangster-figure in Drum". Journal of Southern African Studies. 22 (4): 623. doi:10.1080/03057079608708515. JSTOR 2637160.

- ^ Kynoch, Gary (2005). "Book Review of: Respectability and Resistance: A History of Sophiatown by David Goodhew". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 38 (1). Boston University African Studies Center: 135–136. JSTOR 40036478.

- ^ Fenwick, Mac (1996). "'Tough guy, eh?': The gangster-figure in Drum". Journal of Southern African Studies. 22 (4): 618. doi:10.1080/03057079608708515. JSTOR 2637160.

- ^ a b Davie, Lucille (10 February 2005). "Sophiatown: recalling the loss". City of Johannesburg. IMC. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c "Joburg Heritage: Plaques". Johannesburg Heritage. 3 December 2011. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008.

- ^ Davie, Lucille (1 November 2004). "Sophiatown unveils Sekoto mural". SouthAfrica.info. Originally published by the City of Johannesburg. Archived from the original on 29 August 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Great churches and temples of Joburg". City of Johannesburg. 13 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Sophiatown Heritage and Cultural Centre. Posters at the Sophiatown Heritage and Cultural Centre.

- ^ Modisane, Bloke (1986). Blame me on history. Ad. Donker. pp. 27, 36. ISBN 0-86852-098-5.

- ^ Themba, Can (2006). Requiem for Sophiatown (PDF). Penguin Books. p. 50. ISBN 0-14-318548-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Music and culture as forms of resistance". South African History Online. 3 December 2011. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Harrison, Philip (2012). South Africa's Top Sites: The Struggle. p. 48.

- ^ Davie, Lucille (17 September 2004). "Plan aims to excavate Sophiatown memories". Johannesburg News Agency (www.joburg.org.za). Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Welcome". The Trevor Huddleston Memorial Centre. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Themba, Can (2006). Requiem for Sophiatown (PDF). Penguin Books. p. 51. ISBN 0-14-318548-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Davie, Lucille (8 September 2004). "SA's first champion tree proclaimed in Sophiatown". Johannesburg News Agency (www.joburg.org.za). Retrieved 4 December 2011.

External links

edit| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Clip from an interviewed Victor Mokhini, an ex-resident of Sophiatown |

- South African History Online: Sophiatown

- South African History Online: The Destruction of Sophiatown

- Come Back, Africa by Lionel Rogosin on YouTube

- The Official Lionel Rogosin website

- Come Back, Africa, Lionel Rogosin & Peter Davis, STE Publishers, ISBN 1-919855-17-3 (The book of the film)

- 1955 Time magazine article - Toby Street Blues about the forced removals