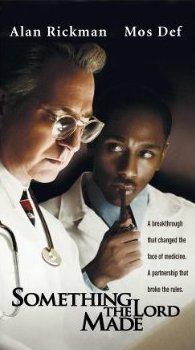

Something the Lord Made is a 2004 American made-for-television biographical drama film about the black cardiac pioneer Vivien Thomas (1910–1985) and his complex and volatile partnership with white surgeon Alfred Blalock (1899–1964), the "Blue Baby doctor" who pioneered modern heart surgery. Based on the National Magazine Award-winning Washingtonian magazine article "Like Something the Lord Made" by Katie McCabe,[1][2] the film was directed by Joseph Sargent and written by Peter Silverman and Robert Caswell.

| Something the Lord Made | |

|---|---|

| |

| Written by | Peter Silverman Robert Caswell |

| Directed by | Joseph Sargent |

| Starring | Mos Def Alan Rickman Kyra Sedgwick Gabrielle Union Mary Stuart Masterson |

| Original language | English |

| Production | |

| Producers | Robert W. Cort David Madden Eric Hetzel Julian Krainin Mike Drake |

| Cinematography | Donald M. Morgan |

| Editor | Michael Brown |

| Running time | 110 mins |

| Production companies | HBO Films Nina Saxon Film Design |

| Original release | |

| Network | HBO |

| Release | May 30, 2004 |

Plot

editSomething the Lord Made tells the story of the 34-year partnership that begins in Depression Era Nashville in 1930 when Blalock (Alan Rickman) hires Thomas (Mos Def) as an assistant at his Vanderbilt University lab, expecting him to perform janitorial work. But Thomas' remarkable manual dexterity and intellectual acumen confound Blalock's expectations, and Thomas rapidly becomes indispensable as a research partner to Blalock in his forays into heart surgery.

The film traces the two men's work when they move in 1943 from Vanderbilt to Johns Hopkins, an institution where the only black employees are janitors and where Thomas must enter by the back door. Together, they attack the congenital heart defect of Tetralogy of Fallot, also known as Blue Baby Syndrome, and in so doing they open the field of heart surgery.

Helen Taussig (Mary Stuart Masterson), the pediatrician/cardiologist at Johns Hopkins, challenges Blalock to come up with a surgical solution for her Blue Babies. She needs a new ductus for them to oxygenate their blood.

The duo is seen experimenting on stray dogs they got from the local dog pound, deliberately giving the dogs the heart defect and trying to solve it. The outcome looks good and they are excited to operate on a baby with the defect, but in a dream, Thomas sees the baby grown up and crying because she's dying. Thomas asks why she's dying in the dream and she says it's because she has a baby heart. Blalock interprets it as the fact that their sewing technique didn't work because the sutures didn't grow with the heart, and worked on a new version that would work.

The film dramatizes Blalock's and Thomas' fight to save the dying Blue Babies. Blalock praises Thomas' surgical skill as being "like something the Lord made", and insists that Thomas coach him through the first Blue Baby surgery over the protests of Hopkins administrators. Yet outside the lab, they are separated by the prevailing racism of the time. Blalock makes a mistake once by accidentally cutting an artery at the wrong place, but eventually, along with Thomas, succeeds. As word quickly spreads of their success, parents all over the country flock to the hospital with their sick children, hoping the surgery will cure them. Also doctors from around the world start attending Thomas's surgery in order to learn how to do the surgery themselves so they can treat their own patients. Thomas attends Blalock's parties as a bartender, moonlighting for extra income, and when Blalock is honored for the Blue Baby work at the segregated Belvedere Hotel, Thomas is not among the invited guests. Instead, he watches from behind a potted palm at the rear of the ballroom. From there, he listens to Blalock give credit to the other doctors who assisted in the work but make no mention of Thomas or his contributions. The next day, Thomas reveals that he saw the ceremony, and quits from his lab. However, his heart is with the work he left behind so much that he is unhappy in other endeavors. He therefore decides to overlook Blalock's lack of acknowledgement and return to the lab.

In 1964, one day before Blalock dies, he sees Thomas, now a professional surgeon and trainer in the open heart surgery wing. After Blalock's death, Thomas continued his work at Johns Hopkins training surgeons. At the end of the film, in a formal ceremony in 1976, Hopkins recognized Thomas' work and awarded him an honorary doctorate. A portrait of Thomas was placed on the walls of Johns Hopkins next to Blalock's portrait, which had been hung there years earlier. A brief montage shows 'DR. ALFRED BLALOCK 1899-1964' over Blalock's portrait, and 'DR. VIVIEN THOMAS: 1910-1985' over Thomas's.

Cast

edit- Alan Rickman as Alfred Blalock

- Mos Def as Vivien Thomas

- Kyra Sedgwick as Mary Blalock

- Gabrielle Union as Clara Thomas

- Merritt Wever as Mrs. Saxon

- Clayton LeBouef as Harold Thomas

- Charles S. Dutton as William Thomas

- Mary Stuart Masterson as Helen B. Taussig

Film background

editA man who in life avoided the limelight, Thomas remained virtually unknown outside the circle of Hopkins surgeons he trained. Thomas' story was first brought to public attention by Washington writer Katie McCabe, who learned of his work with Blalock on the day of his death in a 1985 interview with a prominent Washington, D.C. surgeon who described Thomas as "an absolute legend." McCabe's 1989 Washingtonian magazine article on Thomas, "Like Something the Lord Made",[1] generated widespread interest in the story and inspired the making of a 2003 public television documentary on Thomas and Blalock, "Partners of the Heart."[3] A Washington, D.C. dentist, Irving Sorkin, discovered McCabe's article and brought it to Hollywood, where it was developed into the film.[4][5]

Awards and nominations

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b McCabe, Katie (August 1989). "Like Something the Lord Made". The Washingtonian. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ "Like Something the Lord Made". 2014-11-10. Archived from the original on 2014-11-10. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ Mary Ann Ayd (February 2003). "Almost A Miracle". Dome. Vol. 54, no. 1. The Johns Hopkins University. Archived from the original on 2012-03-02.

- ^ Matt Schudel (November 11, 2007). "Dentist Had Hankering for Show Business". The Washington Post.

- ^ Dennis McLellan (October 25, 2007). "Irving Sorkin, 88; dentist saw Hollywood dream come true as award-winning producer". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "2004 Artios Awards". www.castingsociety.com. Retrieved October 12, 2004.

- ^ "8th Annual TV Awards (2004)". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Something the Lord Made". Emmys.com. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ "American Cinema Editors (ACE) Announces Nominees for 55th Annual ACE Eddie Awards". PRWeb. January 14, 2005. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2004". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "2005 BET Awards Nominees". Billboard. May 16, 2005. Archived from the original on July 17, 2017.

- ^ "Black Reel Awards – Past Winners". Black Reel Awards. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". IMDb. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 2004". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ "57th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Something the Lord Made – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Vivica A. FOX , Omar Epps, Hill Harper, Essence Atkins and Ananda Lewis Join Naacp Executives to Announce the '36th Naacp Image Awards' Nominations". The Futon Critic. Retrieved January 19, 2005.

- ^ "Something the Lord Made". Peabody Awards. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ King, Susan (January 6, 2005). "Producers' '04 nominees". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners – Satellite™ Awards 2005 (9th Annual Satellite™ Awards)". International Press Academy. Satellite Awards. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ "Alphabet tops TCA nominations". Variety. June 2, 2005. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ "Writers Guild Awards Winners: 2005-1996". Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2012.