1960 South African republic referendum

A referendum on becoming a republic was held in South Africa on 5 October 1960. The Afrikaner-dominated right-wing National Party, which had come to power in 1948, was avowedly republican and regarded the position of Queen Elizabeth II as the South African monarch as a relic of British imperialism.[1] The National Party government subsequently organised the referendum on whether the then Union of South Africa should become a republic. The vote, which was restricted to whites—the first such national election in the union—was narrowly approved by 52.29% of the voters.[2][3] The Republic of South Africa was constituted on 31 May 1961.

Background

editAfrikaner republicanism

editDespite the defeat of the two Boer Republics, the South African Republic (also known as the Transvaal) and the Orange Free State, republican sentiment remained strong in the Union of South Africa among Afrikaners.[4] D. F. Malan broke with the National Party of Prime Minister J. B. M. Hertzog when it merged with the South African Party of Jan Smuts to form a Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party (or "Purified National Party") which advocated a South African republic under Afrikaner control. This had the support of the secretive Afrikaner Broederbond organisation, whose chairman, L J du Plessis declared:

National culture and national welfare cannot unfold fully if the people of South Africa do not also constitutionally sever all foreign ties. After the cultural and economic needs, the Afrikaner will have to devote his attention to the constitutional needs of our people. Added to that objective must be an entirely independent genuine, Afrikaans form of government for South Africa... a form of government which through its embodiment in our own personal head of state, bone of our bone, flesh of our flesh, will inspire us to irresistible unity and strength.[5]

In 1940, Malan, along with Hertzog, founded the Herenigde Nasionale Party (or "Reunited National Party") which pledged to fight for "a free independent republic, separated from the British Crown and Empire", and "to remove, step by step, all anomalies which hamper the fullest expression of our national freedom".[6]

That year, a Commission appointed by the Broederbond, met to draft a constitution for a republic; this included future National Party ministers, such as Hendrik Verwoerd, Albert Hertzog and Eben Dönges.[7]

In 1942, details of a draft republican constitution were published in Afrikaans-language newspapers Die Burger and Die Transvaler, which provided for a State President, elected by white citizens known as Burgers only, who would be "only responsible to God... for his deeds in the fulfilment of his duties", aided by a Community Council with exclusively advisory powers, while Afrikaans would be the first official language, with English as a supplemental language.[8]

On the matter of continued Commonwealth membership, the Broederbond's view was that "departure from the Commonwealth as soon as possible remains a cardinal aspect of our republican aim".[9]

During the visit to South Africa by King George VI and his family in 1947, the Afrikaans-language newspaper Die Transvaler, of which Verwoerd was editor, ignored the royal tour, making reference only to "busy streets" in Johannesburg.[10] By contrast, the newspaper of the far-right Ossewa Brandwag openly denounced the tour, proclaiming that "in the name of this monarchy, 27 000 Boer women and children were murdered for the sake of gold and their fatherland".[11]

National Party in government

editIn 1948, the National Party, now led by D. F. Malan, came to power, although it did not campaign for a republic during the election, instead favouring remaining in the Commonwealth, thereby appealing to Afrikaners who otherwise might have voted for the United Party of Jan Smuts.[12] This decision to downplay the republic question and focus on race issues was influenced by N C Havenga, the leader of the Afrikaner Party, which was in alliance with the National Party in the election.[13]

Malan's successor as Prime Minister, J G Strijdom, also downplayed the republic issue, stating that no steps would be taken towards that end before 1958.[14] However, he later reaffirmed his party's commitment to a republic, as well as a single national flag.[15] Strijdom stated that the matter of whether South Africa would be a republic inside or outside the Commonwealth would be decided "with a view to circumstances then prevailing".[16] Like his precessor, Strijdom declared the party's belief that a republic could only be proclaimed on the basis "of the broad will of the people".[17]

On becoming Prime Minister in 1958, Verwoerd gave a speech to Parliament in which he declared that:

This has indeed been the basis of our struggle all these years: nationalism against imperialism. This has been the struggle since 1910: a republic as opposed to the monarchical connection... We stand unequivocally and clearly for the establishment of the republic in the correct manner and at the appropriate time.[18]

In 1960, Verwoerd announced plans to hold a whites-only referendum on the establishment of a republic, with a bill to that effect being introduced in Parliament on 23 April of that year.[19] The Referendum Act received assent on 3 June 1960.[20] He stated that a simple majority in favour of the change would be decisive, although minimal changes would be made to the existing constitutional structures.[21]

Before he was succeeded by Verwoerd as Prime Minister in 1958, Strijdom had lowered the voting age for whites from 21 to 18.[22] Afrikaners, who were more likely to favour the National Party than English-speaking whites, were also on average younger than them, with a higher birth rate.[13] Also included on the electoral roll were white voters in South West Africa, now Namibia.[23] As in South Africa, the Afrikaners and ethnic Germans in the territory outnumbered English-speaking whites, and were strong supporters of the National Party.[24] In addition, Coloureds were no longer enfranchised as voters and were not eligible to vote in the referendum.[25]

In hopes of winning the support of those opposed to a republic, not only English-speaking whites but Afrikaners still supporting the United Party, Verwoerd proposed that constitutional changes would be minimal, with the Queen simply being replaced as head of state by a State President, the office of which would be a ceremonial post rather than an executive one.[26]

Wind of Change speech

editEarlier, in February of that year, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had given a speech to the Parliament in Cape Town, in which he spoke of the inevitability of decolonisation in Africa, and appeared critical of South Africa's apartheid policies.[27] This prompted Verwoerd to declare in the House of Assembly:

It was not the Republic of South Africa that was told, 'We are not going to support you in this respect.' Those words were addressed to the monarchy of South Africa, and yet we have the same monarch as this person from Britain who addressed these words to us. It was a warning given to all of us, English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking, republican and anti-republican. It was clear to all of us that as far as these matters are concerned, we shall have to stand on our own feet.[28]

Many English-speaking whites, who had regarded Britain as their spiritual home, felt disillusionment and a sense of loss, including Douglas Edgar Mitchell, the United Party's leader in Natal.[29] Despite his opposition to Verwoerd's plans for a republic, Mitchell spoke in vehement opposition to many points of Macmillan's speech.[30]

Opposition to republic in Natal

editIn Natal, the only province with an English-speaking majority of whites, there was strong anti-republican sentiment; in 1955, the small Federal Party issued a pamphlet The Case Against the Republic, while the Anti-Republican League organised public demonstrations.[32] The League, founded by Arthur Selby, the Federal Party's chairman, launched the Natal Covenant in opposition to the plans for a republic, signed by 33,000 Natalians.[31] Drawing cheering crowds of 2,000 people in Durban and 1,500 in Pietermaritzburg, the League became the largest political organisation in Natal, with 28 branches across the province, with Selby calling for 80,000 signatories to the Covenant.[33] Inspired by the Ulster Covenant of 1912, the Natal Covenant read:

Being convinced in our consciences that a republic would be disastrous to the material well-being of Natal as well as of the whole of South Africa, subversive of our freedom and destructive of our citizenship, we, whose names are underwritten, men and women of Natal, loyal subjects of Her Gracious Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, do hereby pledge ourselves in solemn covenant, throughout this our time of threatened calamity, to stand by one another in defending the Crown, and in using all means which may be found possible and necessary to defeat the present intention to set up a republic in South Africa. And in the event of a republic being forced upon us, we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority. In sure confidence that God will defend the right, we hereto subscribe our names. GOD SAVE THE QUEEN.[31]

On the day of the referendum, the Natal Witness, the province's daily English-language newspaper warned its readers that:

Not to vote against the Republic is to help those who would cut us loose from our moorings, and set us adrift in a treacherous and uncharted sea, at the very time that the winds of change are blowing up to hurricane force.[34]

Between May 1956 and June 1958, the anti-republican Freedom Radio, set up by John Lang, broadcast from the Natal Midlands, later resuming broadcasts shortly before the referendum in October 1960 until the proclamation of the republic in May 1961.[35]

Black South African opinion

editBlack South Africans, who were denied a vote in the referendum, were not against the establishment of a republic per se, but saw the new constitution as a direct rejection of the principle of one person, one vote, as expressed in the Freedom Charter, drafted by the African National Congress and its allies in the Congress Alliance.[36] Despite its opposition to the monarchy and the Commonwealth, the ANC sought to mobilise white and black opposition to the republic, seeing it as an attempt by Verwoerd to consolidate the white grip on power.[37]

Campaign

edit"Yes" campaign

editThe pro-republic campaign focused on the need for white unity in the face of British decolonisation in Africa, and the eruption of the former Belgian Congo into bloody civil war following independence, which Verwoerd warned might give rise to similar chaos in South Africa.[40] It also argued that South Africa's links with the British monarchy led to confusion about the country's status, with one advertisement proclaiming: "Let us become a real republic now rather than remain betwixt and between".[41]

One campaign poster used the slogan "To re-unite and keep South Africa white, a republic now" on posters in English, while in Afrikaans, the slogan was Ons republiek nou, om Suid-Afrika blank te hou ("Our republic now, to keep South Africa white").[42] Another poster featured two clasped hands, with the slogan "Your people, my people, our republic", which would sometimes be vandalised by painting one of the hands black, producing the emblem of the non-racial Liberal Party.[43]

"No" campaign

editThe opposition United Party actively campaigned for a 'No' vote, arguing that South Africa's membership of the Commonwealth, with which it had privileged trade links, would be threatened and lead to greater isolation.[44] One advertisement pointed out that access to Commonwealth markets was worth £200 000 000 a year.[45] Another proclaimed "You need friends. Don't let Verwoerd lose them all".[46] Sir De Villiers Graaff, the party's leader, called on voters to reject a republic "so we can remain in the British [sic] Commonwealth and have its protection against Communism and hot-eyed African nationalism".[47]

The smaller Progressive Party appealed to supporters of the proposed change to 'reject this republic', arguing that such a weighted electorate could not provide a valid test of opinion.[23] An advertisement appealing to voters who might support a republic declared: "The issue is not monarchy or republic but democracy or dictatorship".[48]

Results

edit| Choice | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| For | 850,458 | 52.29 | |

| Against | 775,878 | 47.71 | |

| Total | 1,626,336 | 100.00 | |

| Valid votes | 1,626,336 | 99.52 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 7,904 | 0.48 | |

| Total votes | 1,634,240 | 100.00 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 1,800,426 | 90.77 | |

| Source: Government Gazette | |||

By province

edit| Province | For | Against | Invalid/ blank |

Total | Registered voters |

Turnout | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||||

| Cape of Good Hope | 271,418 | 50.15 | 269,784 | 49.85 | 2,881 | 544,083 | 591,298 | 92.02 |

| Natal | 42,299 | 23.78 | 135,598 | 76.22 | 688 | 178,585 | 193,103 | 92.48 |

| Orange Free State | 110,171 | 76.72 | 33,438 | 23.28 | 798 | 144,407 | 160,843 | 89.78 |

| South-West Africa | 19,938 | 62.39 | 12,017 | 37.61 | 280 | 32,235 | 37,135 | 86.80 |

| Transvaal | 406,632 | 55.58 | 325,041 | 44.42 | 3,257 | 734,930 | 818,047 | 89.84 |

| Source: Government Gazette Extraordinary (6557) | ||||||||

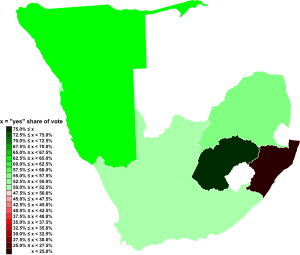

By electoral division

editOf the 156 House of Assembly parliamentary constituencies, a majority voted for a republic in 104 (all 103 won by the National Party in the 1958 general election, plus the United Party-held seat of Sunnyside in Pretoria), while a majority voted against in the other 52 (all held by the United Party or the Progressive Party).[49]

| Province | Constituency | For | Against | Invalid/ blank |

Total | Registered voters[a] |

Turnout | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||||

| Cape of Good Hope | Albany | 2,448 | 23.02 | 8,184 | 76.98 | 47 | 10,679 | 11,606 | 92.01 |

| Aliwal | 5,243 | 58.14 | 3,775 | 41.86 | 53 | 9,071 | 9,583 | 94.66 | |

| Beaufort West | 6,223 | 77.81 | 1,775 | 22.19 | 45 | 8,043 | 8,919 | 90.18 | |

| Bellville | 8,387 | 62.73 | 4,984 | 37.27 | 57 | 13,428 | 14,548 | 92.30 | |

| Ceres | 6,596 | 77.00 | 1,970 | 23.00 | 53 | 8,619 | 9,416 | 91.54 | |

| Constantia | 1,638 | 13.60 | 10,405 | 86.40 | 30 | 12,073 | 13,277 | 90.93 | |

| Cradock | 5,615 | 66.76 | 2,796 | 33.24 | 41 | 8,452 | 9,140 | 92.47 | |

| De Aar—Colesberg | 5,846 | 70.60 | 2,434 | 29.40 | 52 | 8,332 | 9,052 | 92.05 | |

| Fort Beaufort | 4,910 | 55.46 | 3,943 | 44.54 | 52 | 8,905 | 9,327 | 95.48 | |

| George | 7,842 | 76.83 | 2,365 | 23.17 | 51 | 10,258 | 10,969 | 93.52 | |

| Gordonia | 5,925 | 70.72 | 2,453 | 29.28 | 71 | 8,449 | 9,289 | 90.96 | |

| Graaff-Reinet | 5,576 | 68.55 | 2,558 | 31.45 | 66 | 8,200 | 8,876 | 92.38 | |

| Green Point | 1,784 | 16.52 | 9,018 | 83.48 | 39 | 10,841 | 12,350 | 87.78 | |

| Hottentots-Holland | 5,688 | 56.19 | 4,434 | 43.81 | 57 | 10,179 | 10,876 | 93.59 | |

| Humansdorp | 6,269 | 65.04 | 3,369 | 34.96 | 52 | 9,690 | 10,298 | 94.10 | |

| Cape Town Gardens | 3,706 | 31.08 | 8,217 | 68.92 | 47 | 11,970 | 13,467 | 88.88 | |

| Kimberley North | 6,438 | 59.89 | 4,312 | 40.11 | 12 | 10,762 | 11,885 | 90.55 | |

| Kimberley South | 6,067 | 54.33 | 5,099 | 45.67 | 87 | 11,253 | 12,292 | 91.55 | |

| King William’s Town | 3,104 | 29.20 | 7,525 | 70.80 | 27 | 10,656 | 11,294 | 94.35 | |

| Kuruman | 6,225 | 69.11 | 2,782 | 30.89 | 50 | 9,057 | 9,747 | 92.92 | |

| Maitland | 3,866 | 35.48 | 7,029 | 64.52 | 44 | 10,939 | 12,099 | 90.41 | |

| Malmesbury | 7,463 | 74.44 | 2,562 | 25.56 | 92 | 10,117 | 10,790 | 93.76 | |

| Moorreesburg | 6,636 | 74.54 | 2,267 | 25.46 | 67 | 8,970 | 9,738 | 92.11 | |

| Mossel Bay | 6,939 | 75.02 | 2,311 | 24.98 | 71 | 9,321 | 9,984 | 93.36 | |

| Namakwaland | 6,686 | 76.51 | 2,053 | 23.49 | 140 | 8,879 | 9,912 | 89.58 | |

| East London North | 2,294 | 18.95 | 9,812 | 81.05 | 116 | 12,222 | 12,993 | 94.07 | |

| East London City | 2,662 | 23.85 | 8,499 | 76.15 | 53 | 11,214 | 12,391 | 90.50 | |

| Oudtshoorn | 7,342 | 78.05 | 2,065 | 21.95 | 73 | 9,480 | 10,438 | 90.82 | |

| Paarl | 7,314 | 69.08 | 3,273 | 30.92 | 81 | 10,668 | 11,498 | 92.78 | |

| Parow | 9,300 | 75.73 | 2,980 | 24.27 | 68 | 12,348 | 13,582 | 90.91 | |

| Pinelands | 2,143 | 18.26 | 9,593 | 81.74 | 16 | 11,752 | 12,687 | 92.63 | |

| Piketberg | 7,385 | 86.04 | 1,198 | 13.96 | 48 | 8,631 | 9,286 | 92.95 | |

| Port Elizabeth North | 7,143 | 57.67 | 5,244 | 42.33 | 61 | 12,448 | 13,586 | 91.62 | |

| Port Elizabeth Central | 4,149 | 36.30 | 7,280 | 63.70 | 43 | 11,472 | 12,576 | 91.22 | |

| Port Elizabeth South | 2,645 | 21.63 | 9,583 | 78.37 | 33 | 12,261 | 13,217 | 92.77 | |

| Port Elizabeth West | 3,926 | 28.17 | 10,009 | 71.83 | 55 | 13,990 | 14,734 | 94.95 | |

| Prieska | 5,209 | 61.12 | 3,313 | 38.88 | 45 | 8,567 | 9,154 | 93.59 | |

| Queenstown | 5,257 | 49.43 | 5,378 | 50.57 | 14 | 10,649 | 11,112 | 95.83 | |

| Rondebosch | 1,622 | 13.43 | 10,456 | 86.57 | 36 | 12,114 | 13,301 | 91.08 | |

| Sea Point | 1,077 | 9.01 | 10,877 | 90.99 | 38 | 11,992 | 12,798 | 93.70 | |

| Simonstown | 2,591 | 21.92 | 9,229 | 78.08 | 57 | 11,877 | 13,017 | 91.24 | |

| Somerset East | 6,025 | 68.87 | 2,723 | 31.13 | 101 | 8,849 | 9,375 | 94.39 | |

| Salt River | 1,936 | 20.85 | 7,349 | 79.15 | 64 | 9,349 | 10,610 | 88.11 | |

| Stellenbosch | 8,086 | 67.82 | 3,836 | 32.18 | 27 | 11,949 | 13,194 | 90.56 | |

| Swellendam | 5,602 | 59.77 | 3,771 | 40.23 | 70 | 9,443 | 10,103 | 93.47 | |

| Transkeian Territories | 2,316 | 25.93 | 6,616 | 74.07 | 103 | 9,035 | 9,698 | 93.16 | |

| Uitenhage | 8,938 | 65.98 | 4,609 | 34.02 | 77 | 13,624 | 14,624 | 93.16 | |

| False Bay | 6,517 | 58.42 | 4,638 | 41.58 | 42 | 11,197 | 12,408 | 90.24 | |

| Vasco | 7,138 | 63.41 | 4,119 | 36.59 | 56 | 11,313 | 12,660 | 89.36 | |

| Vryburg | 6,408 | 68.57 | 2,937 | 31.43 | 59 | 9,404 | 10,303 | 91.27 | |

| Worcester | 6,793 | 66.63 | 3,402 | 33.37 | 20 | 10,215 | 11,287 | 90.50 | |

| Wynberg | 2,480 | 22.85 | 8,375 | 77.15 | 22 | 10,877 | 11,932 | 91.16 | |

| Natal | Drakensberg | 3,801 | 41.54 | 5,349 | 58.46 | 50 | 9,200 | 9,956 | 92.41 |

| Durban—Berea | 1,010 | 8.34 | 11,098 | 91.66 | 22 | 12,130 | 12,916 | 93.91 | |

| Durban—Musgrave | 823 | 6.93 | 11,053 | 93.07 | 42 | 11,918 | 12,769 | 93.34 | |

| Durban North | 1,282 | 10.09 | 11,426 | 89.91 | 27 | 12,735 | 13,507 | 94.28 | |

| Durban Point | 1,554 | 12.33 | 11,049 | 87.67 | 28 | 12,631 | 14,156 | 89.23 | |

| Durban Central | 1,445 | 13.16 | 9,538 | 86.84 | 21 | 11,004 | 12,120 | 90.79 | |

| Durban-Umbilo | 1,766 | 15.62 | 9,537 | 84.38 | 45 | 11,348 | 12,386 | 91.62 | |

| Durban Umlazi | 2,706 | 23.15 | 8,983 | 76.85 | 32 | 11,721 | 12,675 | 92.47 | |

| Natal South Coast | 1,669 | 17.70 | 7,761 | 82.30 | 14 | 9,444 | 10,206 | 92.53 | |

| Newcastle | 5,793 | 59.98 | 3,865 | 40.02 | 54 | 9,712 | 10,446 | 92.97 | |

| Pietermaritzburg District | 1,890 | 17.84 | 8,705 | 82.16 | 84 | 10,679 | 11,496 | 92.89 | |

| Pietermaritzburg City | 3,689 | 29.12 | 8,978 | 70.88 | 84 | 12,751 | 13,866 | 91.96 | |

| Pinetown | 1,705 | 15.90 | 9,016 | 84.10 | 46 | 10,767 | 11,520 | 93.46 | |

| Umhlatuzana | 3,887 | 29.05 | 9,495 | 70.95 | 50 | 13,432 | 14,473 | 92.81 | |

| Vryheid | 5,613 | 63.87 | 3,175 | 36.13 | 55 | 8,843 | 9,554 | 92.56 | |

| Zululand | 3,666 | 35.81 | 6,570 | 64.19 | 34 | 10,270 | 11,057 | 92.88 | |

| Orange Free State | Bethlehem | 7,689 | 82.56 | 1,624 | 17.44 | 87 | 9,400 | 10,400 | 90.38 |

| Bloemfontein District | 8,773 | 84.33 | 1,630 | 15.67 | 29 | 10,432 | 11,803 | 88.38 | |

| Bloemfontein East | 8,390 | 68.12 | 3,926 | 31.88 | 23 | 12,339 | 14,438 | 85.46 | |

| Bloemfontein West | 8,468 | 65.35 | 4,490 | 34.65 | 22 | 12,980 | 14,551 | 89.20 | |

| Fauresmith—Boshof | 7,174 | 82.08 | 1,566 | 17.92 | 45 | 8,785 | 9,333 | 94.13 | |

| Harrismith | 6,969 | 82.04 | 1,526 | 17.96 | 43 | 8,538 | 9,195 | 92.85 | |

| Heilbron | 8,328 | 78.42 | 2,292 | 21.58 | 85 | 10,705 | 11,751 | 91.10 | |

| Kroonstad | 7,913 | 79.11 | 2,090 | 20.89 | 54 | 10,057 | 11,057 | 90.96 | |

| Ladybrand | 6,315 | 76.25 | 1,967 | 23.75 | 146 | 8,428 | 9,154 | 92.07 | |

| Odendaalsrus | 8,517 | 75.11 | 2,823 | 24.89 | 44 | 11,384 | 13,277 | 85.74 | |

| Smithfield | 6,997 | 81.10 | 1,631 | 18.90 | 58 | 8,686 | 9,247 | 93.93 | |

| Vredefort | 7,343 | 81.08 | 1,713 | 18.92 | 45 | 9,101 | 10,158 | 89.59 | |

| Welkom | 9,437 | 67.01 | 4,647 | 32.99 | 50 | 14,134 | 16,147 | 87.53 | |

| Winburg | 7,858 | 83.85 | 1,513 | 16.15 | 67 | 9,438 | 10,332 | 91.35 | |

| South-West Africa | Etosha | 3,692 | 70.82 | 1,521 | 29.18 | 55 | 5,268 | 6,004 | 87.74 |

| Karas | 2,933 | 58.37 | 2,092 | 41.63 | 44 | 5,069 | 5,533 | 91.61 | |

| Middelland | 3,347 | 61.09 | 2,132 | 38.91 | 36 | 5,515 | 6,247 | 88.28 | |

| Namib | 2,911 | 59.35 | 1,994 | 40.65 | 51 | 4,956 | 5,600 | 88.50 | |

| Omaruru | 3,341 | 65.79 | 1,737 | 34.21 | 45 | 5,123 | 6,063 | 84.50 | |

| Windhoek | 3,714 | 59.38 | 2,541 | 40.62 | 49 | 6,304 | 7,688 | 82.00 | |

| Transvaal | Alberton | 8,154 | 68.48 | 3,753 | 31.52 | 32 | 11,939 | 13,457 | 88.72 |

| Benoni | 4,400 | 40.38 | 6,497 | 59.62 | 36 | 10,933 | 12,266 | 89.13 | |

| Bethal-Middelburg | 5,977 | 66.35 | 3,031 | 33.65 | 54 | 9,062 | 9,897 | 91.56 | |

| Bezuidenhout | 2,279 | 21.44 | 8,352 | 78.56 | 35 | 10,666 | 12,031 | 88.65 | |

| Boksburg | 6,871 | 54.22 | 5,801 | 45.78 | 63 | 12,735 | 13,798 | 92.30 | |

| Brakpan | 6,796 | 61.72 | 4,215 | 38.28 | 22 | 11,033 | 12,496 | 88.29 | |

| Brits | 7,038 | 77.67 | 2,023 | 22.33 | 81 | 9,142 | 10,018 | 91.26 | |

| Christiana | 6,760 | 73.17 | 2,479 | 26.83 | 68 | 9,307 | 9,931 | 93.72 | |

| Edenvale | 7,265 | 59.26 | 4,994 | 40.74 | 46 | 12,305 | 13,932 | 88.32 | |

| Ermelo | 5,745 | 64.30 | 3,190 | 35.70 | 100 | 9,035 | 9,907 | 91.20 | |

| Florida | 4,808 | 40.00 | 7,212 | 60.00 | 16 | 12,036 | 12,823 | 93.86 | |

| Geduld | 7,640 | 64.07 | 4,284 | 35.93 | 40 | 11,964 | 13,520 | 88.49 | |

| Germiston | 6,848 | 66.87 | 3,393 | 33.13 | 53 | 10,294 | 11,940 | 86.21 | |

| Germiston District | 3,972 | 33.11 | 8,026 | 66.89 | 62 | 12,060 | 13,353 | 90.32 | |

| Groblersdal | 7,129 | 79.98 | 1,784 | 20.02 | 56 | 8,969 | 9,811 | 91.42 | |

| Heidelberg | 7,072 | 72.95 | 2,622 | 27.05 | 39 | 9,733 | 10,880 | 89.46 | |

| Hercules | 9,502 | 84.92 | 1,687 | 15.08 | 30 | 11,219 | 13,095 | 85.67 | |

| Hillbrow | 1,285 | 11.64 | 9,757 | 88.36 | 33 | 11,075 | 12,683 | 87.32 | |

| Hospital | 2,162 | 23.78 | 6,929 | 76.22 | 30 | 9,121 | 11,012 | 82.83 | |

| Houghton | 1,153 | 9.85 | 10,555 | 90.15 | 31 | 11,739 | 12,721 | 92.28 | |

| Innesdal | 8,283 | 72.70 | 3,110 | 27.30 | 26 | 11,419 | 12,566 | 90.87 | |

| Jeppes | 3,259 | 33.54 | 6,459 | 66.46 | 47 | 9,765 | 11,647 | 83.84 | |

| Johannesburg North | 1,488 | 12.26 | 10,652 | 87.74 | 23 | 12,163 | 13,067 | 93.08 | |

| Kempton Park | 8,577 | 66.97 | 4,231 | 33.03 | 68 | 12,876 | 14,276 | 90.19 | |

| Kensington | 1,824 | 16.54 | 9,207 | 83.46 | 15 | 11,046 | 12,130 | 91.06 | |

| Klerksdorp | 9,452 | 70.17 | 4,018 | 29.83 | 19 | 13,489 | 15,192 | 88.79 | |

| Krugersdorp | 7,107 | 63.95 | 4,007 | 36.05 | 66 | 11,180 | 12,787 | 87.43 | |

| Langlaagte | 6,853 | 61.76 | 4,244 | 38.24 | 50 | 11,147 | 12,340 | 90.33 | |

| Lichtenburg | 7,333 | 79.55 | 1,885 | 20.45 | 31 | 9,249 | 10,094 | 91.63 | |

| Losberg | 6,231 | 63.87 | 3,525 | 36.13 | 73 | 9,829 | 10,864 | 90.47 | |

| Lydenburg—Barberton | 5,589 | 65.35 | 2,964 | 34.65 | 130 | 8,683 | 9,558 | 90.85 | |

| Maraisburg | 7,412 | 70.81 | 3,055 | 29.19 | 41 | 10,508 | 12,332 | 85.21 | |

| Marico | 5,756 | 68.56 | 2,640 | 31.44 | 39 | 8,435 | 9,073 | 92.97 | |

| Mayfair | 6,278 | 65.49 | 3,308 | 34.51 | 74 | 9,660 | 11,256 | 85.82 | |

| Nelspruit | 6,359 | 66.21 | 3,246 | 33.79 | 18 | 9,623 | 10,548 | 91.23 | |

| Nigel | 6,883 | 64.74 | 3,749 | 35.26 | 29 | 10,661 | 11,660 | 91.43 | |

| North East Rand | 2,875 | 24.29 | 8,959 | 75.71 | 32 | 11,866 | 12,805 | 92.67 | |

| North West Rand | 6,700 | 57.42 | 4,969 | 42.58 | 37 | 11,706 | 12,711 | 92.09 | |

| Orange Grove | 889 | 7.42 | 11,086 | 92.58 | 51 | 12,026 | 12,671 | 94.91 | |

| Parktown | 1,038 | 8.89 | 10,640 | 91.11 | 29 | 11,707 | 12,491 | 93.72 | |

| Pietersburg | 6,925 | 74.67 | 2,349 | 25.33 | 71 | 9,345 | 10,440 | 89.51 | |

| Potchefstroom | 8,288 | 74.13 | 2,893 | 25.87 | 77 | 11,258 | 12,767 | 88.18 | |

| Pretoria District | 7,086 | 65.28 | 3,768 | 34.72 | 33 | 10,887 | 11,845 | 91.91 | |

| Pretoria East | 9,834 | 69.65 | 4,286 | 30.35 | 44 | 14,164 | 15,537 | 91.16 | |

| Pretoria—Rissik | 5,664 | 44.89 | 6,954 | 55.11 | 26 | 12,644 | 13,848 | 91.31 | |

| Pretoria Central | 6,958 | 71.46 | 2,779 | 28.54 | 14 | 9,751 | 11,607 | 84.01 | |

| Pretoria—Sunnyside | 7,774 | 57.59 | 5,724 | 42.41 | 42 | 13,540 | 15,080 | 89.79 | |

| Pretoria West | 8,453 | 75.12 | 2,799 | 24.88 | 54 | 11,306 | 13,324 | 84.85 | |

| Prinshof | 7,709 | 67.28 | 3,749 | 32.72 | 35 | 11,493 | 13,540 | 84.88 | |

| Randfontein | 6,918 | 64.37 | 3,830 | 35.63 | 77 | 10,825 | 11,911 | 90.88 | |

| Roodepoort | 8,074 | 66.18 | 4,126 | 33.82 | 49 | 12,249 | 13,314 | 92.00 | |

| Rosettenville | 2,631 | 22.95 | 8,833 | 77.05 | 46 | 11,510 | 12,834 | 89.68 | |

| Rustenburg | 6,398 | 68.26 | 2,975 | 31.74 | 45 | 9,418 | 10,323 | 91.23 | |

| Soutpansberg | 6,859 | 73.52 | 2,470 | 26.48 | 74 | 9,403 | 10,332 | 91.01 | |

| Springs | 4,525 | 39.08 | 7,053 | 60.92 | 73 | 11,651 | 12,790 | 91.09 | |

| Standerton | 6,003 | 64.00 | 3,376 | 36.00 | 66 | 9,445 | 10,286 | 91.82 | |

| Turffontein | 3,974 | 35.06 | 7,360 | 64.94 | 70 | 11,404 | 12,772 | 89.29 | |

| Vanderbijl Park | 9,497 | 74.63 | 3,229 | 25.37 | 35 | 12,761 | 13,877 | 91.96 | |

| Ventersdorp | 6,695 | 67.64 | 3,203 | 32.36 | 91 | 9,989 | 11,026 | 90.59 | |

| Vereeniging | 6,833 | 57.63 | 5,024 | 42.37 | 55 | 11,912 | 12,948 | 92.00 | |

| Von Brandis | 2,319 | 24.54 | 7,131 | 75.46 | 50 | 9,500 | 11,210 | 84.75 | |

| Wakketstroom | 6,443 | 73.22 | 2,357 | 26.78 | 63 | 8,863 | 9,545 | 92.85 | |

| Waterberg | 7,576 | 85.97 | 1,236 | 14.03 | 38 | 8,850 | 9,652 | 91.69 | |

| Westdene | 6,960 | 65.09 | 3,733 | 34.91 | 28 | 10,721 | 11,936 | 89.82 | |

| Witbank | 6,439 | 68.07 | 3,020 | 31.93 | 34 | 9,493 | 10,683 | 88.86 | |

| Wolmaransstad | 7,192 | 74.98 | 2,400 | 25.02 | 29 | 9,621 | 10,564 | 91.07 | |

| Wonderboom | 8,368 | 82.74 | 1,746 | 17.26 | 70 | 10,184 | 11,667 | 87.29 | |

| Yeoville | 1,195 | 10.58 | 10,100 | 89.42 | 43 | 11,338 | 12,749 | 88.93 | |

Aftermath

editWhite reaction

editWhites in the former Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State voted decisively in favour, as did those in South West Africa. On the eve of the establishment of the republic, Die Transvaler proclaimed:

Our republic is the inevitable fulfilment of God's plan for our people... a plan formed in 1652 when Jan van Riebeeck arrived at the Cape... for which the defeat of our republics in 1902 was a necessary step.[50]

In the Cape Province there was a smaller majority, despite the removal of the Cape Coloured franchise, while Natal voted overwhelmingly against; in the constituencies of Durban North, Pinetown and Durban Musgrave, the vote against a republic was 89.7, 83.7 and 92.7 per cent respectively.[51] Following the referendum result, Douglas Mitchell, the leader of the United Party in Natal, declared:

We in Natal will have no part or parcel of this Republic. We must resist, resist, and resist it - and the Nationalist Government. I have contracted Natal out of a republic on the strongest possible moral grounds that I can enunciate.[52]

Mitchell led a delegation from Natal seeking greater autonomy for the province, but without success.[53] Other whites in Natal went as far as to call for secession from the Union, along with some parts of the eastern Cape Province.[54] However, Mitchell rejected the idea of independence as "suicide", although he did not rule out asking for it in the future.[55]

In a conciliatory gesture to English-speaking whites, and a recognition that some had supported him in the referendum, Verwoerd appointed two English-speaking members to his cabinet.[40]

Black reaction

editOn 25 March 1961, in response to the referendum, the ANC held an All-In African Congress in Pietermaritzburg attended by 1398 delegates from all over the country.[56] It passed a resolution declaring that "no Constitution or form of Government decided without the participation of the African people who form an absolute majority of the population can enjoy moral validity or merit support either within South Africa or beyond its borders".[57]

It called for a National Convention, and the organising of mass demonstrations on the eve of what Nelson Mandela described as "the unwanted republic", if the government failed to call one.[58] He wrote:

The adoption of this part of the resolution did not mean that conference preferred a monarchy to a republican form of government. Such considerations were unimportant and irrelevant. The point at issue, and which was emphasised over and over again by delegates, was that a minority Government had decided to proclaim a White Republic under which the living conditions of the African people would continue to deteriorate.[59]

A three-day general strike was called in protest at the declaration of a republic, but Verwoerd responded by cancelling all police leaves, calling up 5,000 armed reservists of the Citizen Force, and ordering the arrest of thousands in black townships, although Mandela, by now head of the underground movement, managed to escape arrest.[1]

Commonwealth reaction

editOriginally every independent country in the Commonwealth was a Dominion with the British monarch as head of state. The 1949 London Declaration prior to India becoming a republic allowed countries with a different head of state to join or remain in the Commonwealth, but only by unanimous consent of the other members. The governments of Pakistan (in 1956) and, later, Ghana (in 1960) availed themselves of this principle, and the National Party had not ruled out South Africa's continued membership of the Commonwealth were there a vote in favour of a republic.[60]

However, the Commonwealth by 1960 included new Asian and African members, whose rulers saw the apartheid state's membership as an affront to the organisation's new democratic principles. Julius Nyerere, then Chief Minister of Tanganyika, indicated that his country, which was due to gain independence in 1961, would not join the Commonwealth were apartheid South Africa to remain a member.[61] A Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference was convened in March 1961, a year ahead of schedule, to address the issue.[62] In response, Verwoerd stirred up a confrontation, causing many members to threaten to withdraw if South Africa's renewal of membership application was accepted. As a result, South Africa's membership application was withdrawn, meaning that upon its becoming a republic on 31 May 1961, the country's Commonwealth membership simply lapsed.

Many Afrikaners welcomed this as a clean break with the colonial past, along with the recreation of the Boer republics on a larger scale.[63] By contrast, Sir De Villiers Graaff remarked "how utterly alone and isolated our country has become", and called for another referendum on the republic issue, arguing that the end to Commonwealth membership had dramatically changed the situation.[64] Commenting on the enthusiastic welcome Verwoerd received from his supporters on his return, Douglas Mitchell remarked "They are cheering because we have withdrawn from the world. Will they cheer when the world withdraws from us?"[65]

In a speech made following the announcement, Verwoerd said:

I appeal to the English-speaking people of South Africa not to allow themselves to be hurt, though I can feel their sadness. A framework has fallen away, but what is of greater importance is friendship and getting together as one nation – as white people who have to defend their future together. Now there is a chance of standing together – one free country standing together on a basis which is the desire of friendship with Great Britain.[66]

Following the end of apartheid, South Africa rejoined the Commonwealth, thirty-three years to the day that the republic was established.[67]

Establishment of Republic

editInauguration of State President

editThe Republic of South Africa was declared on 31 May 1961, Queen Elizabeth II ceased to be head of state, and the last Governor General of the Union, Charles R. Swart, took office as the first State President.[68] Swart had been elected as State President by Parliament by 139 votes to 71, defeating H A Fagan, the former Chief Justice, favoured by the Opposition.[69]

Legal and heraldic changes

editOther symbolic changes also occurred:

- Legal references to "the Crown" were replaced by those to "the State".[70]

- Oaths of allegiance were no longer to the Queen, but to the Republic of South Africa.[70]

- Queen's Counsels became known as Senior Counsels.[71]

- The "Royal" title was dropped from the names of some South African Army regiments, such as the Natal Carbineers.[72] However, some institutions retained the "Royal" title, such as the Royal Natal National Park and the Royal Society of South Africa[73]

- The mace in the House of Assembly, featuring the Crown at its head, was replaced by a new mace with the coats of arms of the four provinces, as well as sailing ships and ox wagons.[74]

Despite the change to republican status, the coat of arms of Natal continued to display a crown, which had only been added to the arms in 1954, although this was neither the St Edward's Crown, with which the Queen had been crowned, nor the Tudor Crown, used by previous British monarchs, but a distinctive design.[75]

Other references to the monarchy had been removed before the establishment of a republic:

- In 1952, the title of South African Navy vessels HMSAS (His Majesty's South African Ship) had been changed to SAS (South African Ship)[76]

- In 1957, the Crown had been removed from the badges of the defence force and police,[77] or replaced with the Union Lion from the crest of the country's coat of arms[78]

- In 1958, the inscription '"O.H.M.S." (On Her Majesty's Service), used on official mail, was replaced with "On Government Service".[77]

The new decimalised currency, the Rand, which did not feature the Queen's portrait on either notes or coinage, had been introduced on 14 February 1961, three months before the establishment of the Republic.[79] Prior to its introduction, the government considered removing the Queen's head from the coinage of the South African pound.[77]

Constitutional changes

editThe most notable difference between the Constitution of the Republic and that of the Union was that the State President was the ceremonial head of state, in place of the Queen and Governor-General.[68] The title of "State President" (Staatspresident in Afrikaans) was previously used for the heads of state of both the South African Republic[80] and the Orange Free State.[81]

The National Party decided against having an executive presidency, instead adopting a minimalist approach, as a conciliatory gesture to whites who were opposed to a republic;[82] the office did not become an executive post until 1984.[83] Similarly, the Union Jack remained a feature of the country's flag until 1994, despite its unpopularity among many Afrikaners, and a proposal to adopt a new design on the tenth anniversary of the republic in 1971.[84]

Under the new Constitution, Afrikaans and English remained official languages, but the status of Afrikaans in relation to Dutch was altered; whereas the South Africa Act had made Dutch an official language alongside English, with Dutch defined to include Afrikaans under the Official Languages of the Union Act in 1925, the 1961 Constitution reversed this by making Afrikaans an official language alongside English, defining Afrikaans to include Dutch.[85]

Public holidays

editThe change in South Africa's constitutional status also resulted in changes to the country's public holidays, with the Queen's Birthday, commemorated on the second Monday in July,[86] being replaced by Family Day, while Union Day, commemorating the establishment of the Union on 31 May, became Republic Day.[87] Empire Day, which was commemorated on 24 May, but had come to be seen as an anachronism,[88] had been abolished in 1952.[89]

Notes

edit- ^ The total number of registered voters for constituencies is one less than the national figure, with the discrepancy in Transvaal Province.

References

edit- ^ a b South Africa: A War Won, TIME, 9 June 1961

- ^ The Statesman's Year-Book 1975-76, J. Paxton, 1976, Macmillan, page 1289

- ^ "Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd". South African History Online. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

On 5 October 1960 a referendum was held in which White voters were asked "Do you support a republic for the Union?" — 52 percent voted 'Yes'.

- ^ South Africa, Department of Information, 1986, page 131

- ^ Ethnic Nationalism and State Power: The Rise of Irish Nationalism, Afrikaner Nationalism and Zionism, M. Suzman, Macmillan, 2016, page 151

- ^ Christian Nationalism and the Rise of the Afrikaner Broederbond in South Africa, 1918-48, Charles Bloomberg, Macmillan, page 159

- ^ Oxwagon Sentinel: Radical Afrikaner Nationalism and the History of the 'Ossewabrandwag, Christoph Marx, LIT Verlag Münster, 2009, page 405

- ^ Afrikaner Politics in South Africa, 1934-1948, Newell M Stultz, University of California Press, 1974, page 82

- ^ The Diplomacy of Isolation: South African Foreign Policy Making, Deon Geldenhuys, South African Institute of International Affairs, Macmillan, 1984, page 31

- ^ Afrikaners: Their Last Great Trek, Graham Leach, Macmillan London, 1989, page 37

- ^ The Lion and the Springbok: Britain and South Africa Since the Boer War, Ronald Hyam, Peter Henshaw, Cambridge University Press, 2003, page 280

- ^ Turning Points in History, Book 4, Bill Nasson, Rob Siebörger, Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, 2004

- ^ a b Reid, B. L. (1982). "The Anti-Republican League of the 1950s". South African Historical Journal. 14: 85–94. doi:10.1080/02582478208671568.

- ^ STRIJDOM ABATES ZEAL FOR REPUBLIC; Premier Says He Will Not Try to Change South Africa's Status Before 1958, The New York Times, 15 September 1955

- ^ STRIJDOM DETAILS REPUBLIC POLICY; South African Chief Pledges One Flag, One People, but Will Retain Race Laws, The New York Times, 20 December 1955

- ^ South Africa and the World: The Foreign Policy of Apartheid, Amry Vandenbosch, University Press of Kentucky, 2015, page 180

- ^ South African Republicanism, Toledo Blade, 30 January 1958

- ^ The Rise of Afrikanerdom: Power, Apartheid, and the Afrikaner Civil Religion, T. Dunbar Moodie, University of California Press, 1975, page 283

- ^ White Laager: The Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism, William Henry Vatcher, Praeger, 1965, pages 171-172

- ^ Statutes of the Union of South Africa, Government Print. and Stationery Office, 1960, page xi

- ^ Parliaments of South Africa, J J N Cloete, J.L. van Schaik, 1985, page 49

- ^ Nationalism and New States in Africa: From about 1935 to the Present, Ali AlʼAmin Mazrui, Michael Tidy, Heinemann Educational Books, 1984, page 162

- ^ a b South Africa: A Modern History, T. Davenport, C. Saunders, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, page 416

- ^ Afrikaner Politics in South Africa, 1934-1948, Newell M. Stultz, University of California Press, 1974, pp. 160-1 161

- ^ General Elections in South Africa: 1943-1970, Kenneth A. Heard, Oxford University Press, 1974, ages 102-115

- ^ The White Tribe of Africa, David Harrison, University of California Press, 1983, pp. 160-161

- ^ Winds of Change secrets revealed, Independent Online, 5 October 2012

- ^ The White Tribe of Africa, David Harrison, University of California Press, 1983, page 163

- ^ Power, Pride & Prejudice: The Years of Afrikaner Nationalist Rule in South Africa, Henry Kenney J. Ball Publishers, 1991

- ^ The Bell Tolls In Africa Archived 26 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Tablet, 5 March 1960

- ^ a b c Jeffery, Keith (1996). An Irish Empire?: Aspects of Ireland and the British Empire. Manchester University Press. pp. 199–201. ISBN 9780719038730.

- ^ Natalians First: Separatism in South Africa, 1909-1961, Paul Singer Thompson, Southern Book Publishers, 1990, pages 154-156

- ^ South African Historical Journal, Issues 14-18, South African Historical Society, 1982, page 90

- ^ Whirlwind, Hurricane, Howling Tempest: The Wind of Change and the British World, Stuart Ward, in The Wind of Change: Harold Macmillan and British Decolonization, L. Butler, S. Stockwell, Springer, 2013, page 55

- ^ The Road to Democracy in South Africa: 1960-1970 Archived 12 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, South African Democracy Education Trust, Zebra, 2004, page 216

- ^ A Life for Freedom: The Mission to End Racial Injustice in South Africa, Denis Goldberg, University Press of Kentucky, 2015, page 50

- ^ The Lion and the Springbok: Britain and South Africa Since the Boer War, Ronald Hyam, Peter Henshaw, Cambridge University Press, 2003, page 301

- ^ Statutes of the Union of South Africa, Government Print and Stationery Office, 1960, page 666

- ^ Guelke, Adrian (2005). Rethinking the Rise and Fall of Apartheid. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 101. ISBN 9780230802209.

- ^ a b The History of South Africa, Roger B. Beck, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, page 147

- ^ NOW IS THE TIME FOR OUR REPUBLIC!!, Various Referendum campaign posters for and against becoming a republic 1960, University of South Africa Institutional Repository, 17 May 2013

- ^ Architect of Apartheid: H.F. Verwoerd, an Appraisal, Henry Kenney, J. Ball, 1980, page 199

- ^ The Central African Examiner, Volume 4, page 177

- ^ South Africa's Foreign Policy, 1945-1970, James P. Barber, Oxford University Press, 1973, page 120

- ^ YOU WILL SUFFER IF WE LOSE COMMONWEALTH MARKETS, Various Referendum campaign posters for and against becoming a republic 1960, University of South Africa Institutional Repository, 17 May 2013

- ^ YOU NEED FRIENDS, Various Referendum campaign posters for and against becoming a republic 1960, University of South Africa Institutional Repository, 17 May 2013

- ^ Fresh Attack In Britain On Verwoerd, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 October 1960

- ^ YOUR VOTE IS VITAL, Various Referendum campaign posters for and against becoming a republic 1960, University of South Africa Institutional Repository, 17 May 2013

- ^ General Elections in South Africa, 1943-1970, Kenneth A. Heard, Oxford University Press, 1974, page 116

- ^ Christian Nationalism and the Rise of the Afrikaner Broederbond in South Africa, 1918-48, Charles Bloomberg, Macmillan, 1989, page xxi

- ^ Natalians First: Separatism in South Africa, 1909-1961, Paul Singer Thompson, Southern Book Publishers, 1990, page 167

- ^ The Biography of Douglas Mitchell, Terry Wilks, King & Wilks Publishers, 1980, page 42

- ^ Architect of Apartheid: H.F. Verwoerd, an Appraisal, Henry Kenney, J. Ball, 1980, page 202

- ^ Secession Talked by Some Anti-Republicans, Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, 11 October 1960

- ^ Natal Told Not to Be Hasty, The Age, 11 October 1960

- ^ All-In African Congress Archived 9 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine African National Congress

- ^ Nelson Mandela: The Struggle Is My Life, Popular Prakashan, 1990, page 97

- ^ Nelson Mandela: A Life in Photographs, David Elliot Cohen, John D. Battersby, Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2009, page 61

- ^ No Easy Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela, Heinemann, 1973, page 91

- ^ The Conservative Government and the End of Empire 1957-1964: Economics, international relations, and the Commonwealth, Ronald Hyam, Stationery Office, 2000, page 409

- ^ Murphy, Philip (December 2013). Monarchy and the End of Empire: The House of Windsor, the British Government, and the Postwar Commonwealth. Oxford: OUP. p. 74. ISBN 9780199214235.

- ^ South Africa Vote Indicates Nation Will Break Ties To Commonwealth, Toledo Blade, 6 October 1960

- ^ South Africa: Background to the Crisis, Michael Attwell, Sidgwick & Jackson, page 97

- ^ Decision to quit was "inevitable", The Sun-Herald, 19 March 1961

- ^ Douglas Mitchell (1896-1988): A Personal Memoir, Natalia, Volume 19, 1989, page 64

- ^ The New Republic Glasgow Herald, 30 May 1961

- ^ South Africa returns to the Commonwealth fold, The Independent, 31 May 1994

- ^ a b South African Government, Anthony Hocking, Macdonald South Africa, 1977, page 8

- ^ South African Law Journal, Volume 78, Juta, 1961, page 249

- ^ a b Justice of the Peace and Local Government Review, Volume 125, Justice of the Peace Limited, 1961, page 1875

- ^ The Oxford Companion to Law, David M. Walker, 1980, page 1162

- ^ Web of Experience: An Autobiography, Jack Vincent, J. Vincent, 1988, page 38

- ^ home page of Royal Society of South Africa web site

- ^ The Mace of Parliament Archived 5 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, InSession, Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, January–February 2013

- ^ Heraldry In Natal, The Natal Society's Annual Lecture delivered by the State Herald, Frederick Gordon Brownell, on Friday 27 March 1987, Natalia, page 18

- ^ Scientiae Militaria, Volume 27, Faculty of Military Science (Military Academy), University of Stellenbosch, 1997, page 71

- ^ a b c South African Republicanism, Reuters, Toledo Blade, 30 January 1958

- ^ The South African flag book: the history of South African flags from Dias to Mandela, A. P. Burgers, Protea Book House, 2008, page 166

- ^ From Van Riebeeck to Madiba Archived 20 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Witness, 12 September 2012

- ^ South African Treaties, Conventions, Agreements and State Papers, Subsisting on the 1st Day of September, 1898: Compiled by Order of the Right Honourable Sir J. Gordon Sprigg, Prime Minister, W. A. Richards & Sons, 1898, page 48

- ^ Sketch of the Orange Free State of South Africa, Orange Free State. Commission at the International Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876, pages 10-12

- ^ The White Tribe of Africa, David Harrison, University of California Press, 1983, page 161

- ^ South Africa's Foreign Policy: The Search for Status and Security, 1945-1988, James Barber, John Barratt, CUP Archive, 1990, page 292

- ^ New flag Glasgow Herald, 12 September 1968

- ^ Mixed Jurisdictions Worldwide: The Third Legal Family, Vernon V. Palmer, Cambridge University Press, 2001, page 141

- ^ State of South Africa; Economic, Financial and Statistical Yearbook for the Union of South Africa, Closer Union Society, Da Gama Publishers, 1961, page 127

- ^ Statutes of the Republic of South Africa, Part 2, Government Printer, 1961, page 1046

- ^ Debates of the House of Assembly, Volume 76, Cape Times, 1952, page 10231

- ^ Debates of the House of Assembly, Volume 77, Cape Times, 1952, page 1495

External links

edit- South Africa Votes Republican (1960), British Pathé

- South Africa Goes (1961), British Pathé

- South Africa Inaugurates First President AKA Republic Day South Africa (1961), British Pathé

- Dr. Verwoerd Makes A Statement As South Africa Becomes A Republic (1961), British Pathé

- Various Referendum campaign posters for and against becoming a republic. Dated 1960., University of South Africa