This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

A wormhole is a postulated method, within the general theory of relativity, of moving from one point in space to another without crossing the space between.[1][2][3][4] Wormholes are a popular feature of science fiction as they allow faster-than-light interstellar travel within human timescales.[5][6][7]

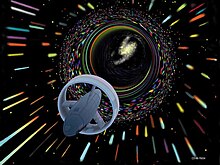

| Wormhole | |

|---|---|

Artist's impression of wormhole travel | |

| Created by | Einstein–Rosen |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| In-universe information | |

| Location | Space |

| Type | Transportation |

| Classification | Pseudo-scientific fiction |

| First proposed | 1916 |

| Re-proposed | 1935 |

A related concept in various fictional genres is the portable hole. While there's no clear demarcation between the two, this article deals with fictional, but pseudo-scientific, treatments of faster-than-light travel through space.

A jumpgate is a fictional device able to create an Einstein–Rosen bridge portal (or wormhole), allowing fast travel between two points in space.

In franchises

editStargate franchise

editWormholes are the principal means of space travel in the Stargate movie and the spin-off television series, Stargate SG-1, Stargate Atlantis and Stargate Universe, to the point where it was called the franchise that is "far and away most identified with wormholes".[8]

The central plot device of the programs is an ancient transportation network consisting of the ring-shaped devices known as Stargates, which generate artificial wormholes that allow one-way matter transmission and two-way radio communication between gates when the correct spatial coordinates are "dialed". However, for some reason not yet explained, the water-like event horizon breaks down the matter and converts it into energy for transport through the wormhole, restoring it into its original state at the destination. This would explain why electromagnetic energy can travel both ways — it doesn't have to be converted.

The one-way rule may be caused by the Stargates themselves: as a Gate may only be capable of creating an event-horizon that either breaks down or reconstitutes matter, but not both. It does serve as a very useful plot device: when one wants to return to the other end one must close the original wormhole and "redial", which means one needs access to the dialing device. The one-way nature of the Stargates helps to defend the gate from unwanted incursions.[9] Also, Stargates can sustain an artificial wormhole for only 38 minutes. It's possible to keep it active for a longer period, but it would take immense amounts of energy. The wormholes generated by the Stargates are based on the misconception that wormholes in 3D space have 2D (circular) event horizons, but a proper visualization of a wormhole in 3D space would be a spherical event horizon.[10][11]

Babylon 5 and Crusade

editIn television series Babylon 5 and its spin-off series Crusade, jump points are artificial wormholes that serve as entrances and exits to hyperspace, allowing for faster-than-light travel. Jump points can either be created by larger ships (battleships, destroyers, etc.) or by standalone jumpgates.

In the B5 universe, jumpgates are considered neutral territory. It is considered a gross violation of normal rules of engagement to attack them directly, as the jumpgate network is needed by every spacefaring race. However, in wartime, it is common for powers to program their gates to deny access to opposing sides, thus forcing enemies to use their own jump points. [11]

Farscape

editThe television series Farscape features an American astronaut who accidentally gets shot through a wormhole and ends up in a distant part of the universe, and also features the use of wormholes to reach other universes (or "unrealized realities") and as weapons of mass destruction.[12][13]

Wormholes are the cause of John Crichton's presence in the far reaches of our galaxy and the focus of an arms race of different alien species attempting to obtain Crichton's perceived ability to control them. Crichton's brain was secretly implanted with knowledge of wormhole technology by one of the last members of an ancient alien species. Later, an alien interrogator discovers the existence of the hidden information and thus Crichton becomes embroiled in interstellar politics and warfare while being pursued by all sides (as they want the ability to use wormholes as weapons). Unable to directly access the information, Crichton is able to subconsciously foretell when and where wormholes will form and is able to safely travel through them (while all attempts by others are fatal). By the end of the series, he eventually works out some of the science and is able to create his own wormholes (and shows his pursuers the consequences of a wormhole weapon).[13][14]

Star Trek franchise

edit- Early in the storyline of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, an antimatter imbalance in the refitted Enterprise starship's warp drive power systems creates an unstable ship-generated wormhole directly ahead of the vessel, threatening to rip the starship apart partially through its increasingly severe time dilation effects, until Commander Pavel Chekov fires a photon torpedo to blast apart a sizable asteroid that was pulled in with the starship (and directly ahead of it), destabilizing the wormhole effect and throwing the Enterprise clear as it slowed to sub-light velocities. Near the end of the film, Willard Decker recalls that "Voyager 6" (a.k.a. V'ger) disappeared into what they used to call a "black hole". At one time, black holes in science fiction were often endowed with the traits of wormholes. This has for the most part disappeared as a black hole isn't a hole in space but a dense mass and the visible vortex effect often associated with black holes is merely the accretion disk of visible matter being drawn toward it. Decker's line is most likely to inform that it was probably a wormhole that Voyager 6 entered, although the intense gravity of a black hole does warp the fabric of spacetime.[15]

- In Star Trek: The Next Generation, in episode "A Matter of Time", Captain Jean-Luc Picard acknowledged that since the first wormholes were discovered students had been asked questions about the ramifications of accidentally changing history for the worse through knowledge obtained by traveling through wormholes.

- The setting of the television series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine is a space station, Deep Space 9, located near the artificially-created Bajoran wormhole.[16] This wormhole is unique in the Star Trek universe because of its stability. In an earlier episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation it was established that wormholes are generally unstable on one or both ends – either the end(s) move erratically or they do not open reliably.[17][18] The Bajoran wormhole is stationary on both ends and opens consistently. It provides passage to the distant Gamma Quadrant, opening a gate to starships that extends far beyond the reach normally attainable, is the source of a severe threat to the Alpha Quadrant from an empire called the Dominion, and is home to a group of non-physical life forms which make contact with Commander Benjamin Sisko and have also interacted with the Bajorans in the past. Discovered at the start of the series, the existence of the wormhole and the various consequences of its discovery elevate the strategic importance of the space station and is a major factor in most of the overarching plots over the course of the series.[16][19][20]

- In Star Trek: Voyager, in episode "Counterpoint", an alien scientist explains that the term wormhole[21] is often used as a layman's term and describes various spatial anomalies. Examples for those wormholes in Star Trek are intermittent cyclical vortex,[22] interspatial fissure,[23] interspatial flexure[23] or spatial flexure in episode "Q2" respectively spatial vortex[24] in episode "Night". In the episode "Inside Man" an artificially created wormhole was named geodesic fold.[25]

- In the 2009 Star Trek film, red matter is used to create artificial black holes. A large one acts a conduit between spacetime and sends Spock and Nero back in time.[26][27]

Doctor Who

edit- The Rift which appears in the long-running British science-fiction series Doctor Who and its spin-off Torchwood is a wormhole. One of its mouths is located in Cardiff Bay, Wales and the other floats freely throughout space-time. It is the central plot device in the latter show.[28]

- In "Planet of the Dead", a wormhole transports a London double-decker bus to a barren, desert-like planet. The wormhole could only be navigated safely through by a metal object, and human tissue is not meant for inter-space travel, as demonstrated by the bus driver, who is burnt to the bones on attempting to get back to Earth.[29][30]

It is discussed that the Time Vortex was created by the Time Lords (an ancient and powerful race of human-looking aliens that can control space and time; the protagonist is one of them) to allow travel of TARDISes (Time And Relative Dimension In Space) to any point in spacetime.[31][32]

Marvel Cinematic Universe

edit- In the 2011 film Thor, the Bifrost is reimagined as an Einstein–Rosen Bridge which is operated by the gatekeeper, Heimdall, and used by Asgardians to travel between the Nine Realms.[33][34]

- In the 2012 film The Avengers, Loki uses the Tesseract to arrive on Earth and summon the Chitauri to invade New York.[35][36]

- In the 2013 film Thor: The Dark World, the Bifrost Bridge is repaired using the Tesseract, and is once again used by Asgardians for space travel. Additionally, Jane Foster and her associates encounter a wormhole in London which teleports her to Svartalfheim.[37][38]

- In the 2017 film Thor: Ragnarok, Thor is teleported to the planet Sakaar via a wormhole, where he learns that Bruce Banner and Loki had both landed on the planet via wormholes as well. The largest one, referred to as the "Devil's Anus", is described by Banner as "a collapsing Neutron Star within an Einstein-Rosen Bridge".[39][40]

- In the 2018 film Avengers: Infinity War, Thanos acquires the Space Stone from the Statesman and uses it to generate wormholes and travel between different points of the Universe.[41]

In literature

editIn some earlier analyses of general relativity, the event horizon of a black hole was believed to form an Einstein-Rosen bridge.[42][43]

| Title | Author | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| "The Meteor Girl" | Jack Williamson | 1931 | In the short story the protagonist creates a "distortion of space-time coordinates" from the effect scientific equipment has on a recently crashed meteor – which is energized with a mystery force. He uses the window in space-time and his knowledge of Einstein's relativity equations to rescue his fiancée from a shipwreck four thousand miles away and twelve hours and 40 minutes in the future.[44][45] |

| The Forever War | Joe Haldeman | 1974 | In the classic war novel interstellar travel is achieved through gateways located at collapsars. This is an early word for a black hole, and the novel refers to the (now obsolete) theory that black holes may contain Einstein–Rosen Bridges.[46][47] |

| Contact | Carl Sagan | 1985 | In the novel a crew of five humans make a trip to the center of the Milky Way galaxy through a transportation system consisting of a series of wormholes.[48] The novel is notable in that Kip Thorne advised Sagan on the possibilities of wormholes.[49][50] Likewise, wormholes are also central to the film version.[51] |

| Vorkosigan Saga | Lois McMaster Bujold | 1986 | In the series naturally occurring wormholes form the basis for interstellar travel. The world of Barrayar was isolated from the rest of human civilization for centuries after the connecting wormhole collapsed, until a new route was discovered, and control over wormhole routes and jumps is the frequent subject of political plots and military campaigns.[52][53] |

| Xeelee series | Stephen Baxter | 1989 | In the fictional world human beings use wormholes to traverse the solar system.[54] A wormhole is also used in this universe to put a probe into the sun (the wormhole is utilized to cool the probe, throwing out solar material fast enough to keep the probe at operating temperatures). In his book Ring, the Xeelee construct a gigantic wormhole into a different universe which they use to escape the onslaught of the Photino birds.[55][self-published source?] |

| Honorverse series | David Weber | 1994 | In this fictional universe, wormholes have an important impact in the economy of the different star nations, as it greatly reduces travel time between two different points. The Star Kingdom of Manticore, to which the main character belongs, is a powerful economic entity thanks to the Manticore Junction, a set of six (a seventh being discovered during the course of the books) wormholes, close to Manticore's binary system, that ensure much travel goes through their system. It also can play a role in the military side of things, but usage of the wormhole destabilizes it for a time proportional to the size of the starship using it.[56] |

| His Dark Materials | Philip Pullman | 1995 | Wormholes are an immensely important plot device in the trilogy, with one first discovered by protagonist Will Parry, when fleeing from his home after an accidental murder; he finds a window in the air in an Oxford street which leads to a totally different universe, the town of Cittagazze. In the rest of the trilogy, the other main characters use wormholes in the form of these extradimensional windows in order to travel "between worlds" and thus speed their journeys.[57][better source needed][58] |

| Einstein's Bridge | John G. Cramer | 1997 | The novel features travel via wormholes between alternate universes.[59][60][61] |

| Diaspora | Greg Egan | 1997 | The novel features scientifically well founded depictions of wormholes.[62][63] |

| Timeline | Michael Crichton | 1999 | In the novel traversable wormholes are used for time travel along with the theory of quantum foam.[64][65] |

| The Light of Other Days | Arthur C. Clarke and Stephen Baxter | 2000 | The novel discusses the problems which arise when a wormhole is used for faster-than-light communication. In the novel the authors suggest that wormholes can join points distant either in time or in space and postulate a world completely devoid of privacy as wormholes are increasingly used to spy on anyone at any time in the world's history.[66][67] |

| Commonwealth Saga | Peter F. Hamilton | 2002 | The series describes how wormhole technology could be used to explore, colonize and connect to other worlds without having to resort to traditional travel via starships. This technology is the basis of the formation of the titular Intersolar Commonwealth, and is used so extensively that it is possible to ride trains between the planets of the Commonwealth.[68] |

| The Algebraist | Iain M. Banks | 2004 | In the novel traversable wormholes can be artificially created and are a central factor/resource in the stratification of space-faring civilizations.[69][70][71] |

| House of Suns | Alastair Reynolds | 2008 | The novel features a wormhole to Andromeda. One main character also alludes to other wormhole mouths leading to galaxies in the Local Group and beyond. In the books, all wormhole-linked galaxies are cloaked by Absences, which prevent information escaping the galaxy and thus protecting causality from being violated by FTL travel.[72] |

| Palimpsest | Charles Stross | 2009 | An original story in the 2009 collection Wireless: The Essential Charles Stross – which won the 2010 Hugo Award for Best Novella[73] – the protagonist creates and uses temporary wormholes to travel through both space and time.[74] |

| "Bright Moment" | Daniel Marcus | 2011 | The short story includes a wormhole for interstellar travel, which can be collapsed to what the story calls a singularity by a multi Gigaton thermonuclear explosion. The story first appeared in F&SF, and was later narrated on the Escape Pod podcast, episode 421.[75][76] |

| The Expanse | James S.A Corey | 2012 | A virus shot at the Solar System millions of years ago constructs a ring in space that creates a wormhole to another dimension which is a "hub" of 1373 wormholes that lead to other solar systems.[77] |

| Waste of Space | Gina Damico | 2017 | This young-adult novel involves a secretive group of scientists dubbed NASAW (revealed at the end of the book to stand for the 'National Association for the Search of Atmospheric Wormholes') whose experiments create a wormhole that a protagonist travels through.[78][better source needed][79] |

In music

edit| Album/Song | Description |

|---|---|

| Universal Migrator Part 2: Flight of the Migrator | On Ayreon's album, Universal Migrator Part 2: Flight of the Migrator, a soul is sucked into a black hole in the song "Into the Black Hole", goes through a wormhole in the song "Through the Wormhole", and leaves from a white hole in the song "Out of the White Hole".[80] |

| Crack the Skye | Mastodon's concept album Crack the Skye deals with a paraplegic child sucked into a wormhole.[81][82] |

In games

edit| Game | Description |

|---|---|

| Portal and Portal 2 | The games Portal and Portal 2 are centered around the "Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device", also known as the "Portal Gun", a gun-shaped device that can create a temporary wormhole between two surfaces.[83][84][85] |

| Space Rogue | The science fiction computer game Space Rogue featured the use of technologically harnessed wormholes called "Malir gates" as mechanisms for interstellar travel. Navigation through the space within wormholes was a part of gameplay and had its own perils.[86] |

| Freelancer | Wormholes are also seen in the computer game Freelancer, commonly referred as "jump holes". They are supposed to be black hole-like formations with ultra-high gravity amounts, that work like 'portals' for players to travel instantly between different star systems. The game also features "jump gates", which are described as devices capable of generating an artificial jump hole.[87][88] |

| Darkspace | In the Massively Multiplayer Online Game Darkspace, a player-versus-player starship combat game, players can create short-term stable wormholes to traverse the game's universe instantly, rather than use the game's concept of FTL travel to move from point A to point B. Wormhole Generation Devices are only available on ships with higher rank requirements, usually Vice Admiral or above, and are most common on Space Stations.[89] |

| Orion's Arm | In the on-line fictional collaborative world-building project "Orion's Arm", wormholes are used for communication and transport between the millions of colonies in the local part of the Milky way Galaxy. In an attempt to make the physics of the wormhole travel at least semi-plausible, large amounts of ANEC-violating exotic energy are required to maintain the holes, which are nevertheless large objects which must be maintained on the outermost reaches of the planetary systems concerned.[90][91] |

| X computer game series | In the X computer game series by Egosoft, wormholes were established using Jump Gates, created by the Old Ones. These Jump Gates connected to many systems but not the Solar System. Humanity advanced to the technological level to create Jump Gate technology and discovered the already established gate network. Hundreds of years after cutting themselves off from the network to escape the Xenon, they created a Jumpdrive, allowing for travel between systems not connected directly via a gate. Different versions of Jumpdrives emerged with some being limited but stable, others being dangerously random.[92][93] |

| Metroid Prime 3: Corruption | In Metroid Prime 3: Corruption, Phazon-based organic meteors called Leviathans create wormholes to travel from Phaaze (the living planet they are "born" in) to other planets. They do this to "corrupt" the planet and any beings able to survive the Phazon into Phazon-based creatures. The planet would then progress into changing its environment until it becomes another planet like Phaaze. The Galactic Federation took control of one with Samus Aran's assistance, and used it to travel to and destroy Phaaze.[94][95] |

| Far Gate | Wormholes are used frequently in Far Gate as a means of transporting spacecraft across interstellar distances.[96][97] |

| Star Trek: Shattered Universe | In Star Trek: Shattered Universe, while in the Mirror Universe, the USS Excelsior (NCC-2000) encounters a wormhole similar to the one the USS Enterprise NCC-1701 in Star Trek: The Motion Picture the player must defend Excelsior from on coming asteroids and pursuing Starships of the Terran Empire, the evil Mirror Universe counterpart of the United Federation of Planets, until the ship can exit the wormhole.[98] |

| Crysis 3 | In Crysis 3, the Alpha Ceph combines its energy with the energy of a C.E.L.L. orbital strike to create an Einstein–Rosen Bridge, thus allowing a Stage Three Ceph Invasion Force to be rapidly transported from Messier 33 to Earth in a matter of minutes.[99][100] |

| EVE Online | Stargates, also known as jump gates, are the primary means of interstellar travel for players in EVE Online. In-universe, the exact way in which jump gates function is unknown: "While functions of jump gates are well known from a theoretical point of view, there still remain a lot of unanswered questions about the fundamentals of dimensional inter-connections."[101][102] In 2009, the expansion Apocrypha added wormholes to the game, which differ from stargates by being less stable and more random and adding an entire new dimension to the game.[103][104][105][106] |

| Stellaris | The science-fiction strategy game Stellaris features wormholes spread throughout the galaxy. The player may research technology to stabilize wormholes and travel through them to reach a linked wormhole elsewhere in the galaxy.[107][108] |

| Command & Conquer 3: Tiberium Wars | One of the three main factions, the Scrin, can construct a "Rift Generator", their in-game superweapon, which creates a wormhole that pulls in nearby units to deep space.[109] Additionally, The Scrin have an ability to create wormholes to instantly teleport units around the battlefield, so long as they have a building called "Signal Transmitter". |

In television and film fiction

edit| Film/episode | Description |

|---|---|

| The Triangle | The 2005 three-part US-British-German science fiction miniseries The Triangle uses a wormhole to explain mysterious disappearances in the Bermuda Triangle.[110][111] |

| Invader Zim | In an episode of the animated series Invader Zim wherein Zim, in order to get rid of Dib and his horrible classmates once and for all, utilizes a wormhole to send Dib and the other Skoolkids on a one-way busride to an alternate dimension containing a room with a moose. However, Dib discovers Zim's plan, and taking advantage of a fork in the wormhole, is able to transport the bus back to Earth.[112][113] |

| Event Horizon | In the movie Event Horizon, the titular ship is designed to create an artificial wormhole. However, the wormhole doesn't lead to anywhere in the known universe, but to an alternate, horrific reality.[114][115][116] |

| Fringe | In the television series Fringe, the main storyline is the investigation of an unusual series of events and scientific experiments called the Pattern. In the second-season episode "Peter" it's revealed that the root cause of the Pattern was an incident in 1985 where Dr. Walter Bishop opened a wormhole into an alternate universe so that he may cure the alternate version of his terminally ill son, Peter (who had died in our universe). By crossing the wormhole, Dr. Bishop disrupted the fundamental laws of nature and weakened the fabric of space-time, causing incalculable destruction in the alternate universe and forcing them to seek a way to repair the damage caused and save their existence.[117][118][119] |

| Power Rangers Time Force | In Power Rangers Time Force, artificial Temporal Wormholes were used extensively for the delivery of the Time Fliers to travel to the past to aid the Rangers and was also used by Wes, Eric and Commandocon to travel to prehistoric times to recover the Quantasaurus Rex. In Power Rangers SPD, in the episode Wormhole, Gruumm and later the SPD Rangers used a "Temporal Wormole" to travel from 2025 to 2004 to battle with the Dino Thunder Rangers in early 21st century Reefside.[120] |

| "Vanishing Act" (The Outer Limits episode) | The 21st episode of the 1995 Canadian science fiction TV series The Outer Limits, "Vanishing Act", tells the story of a man who is abducted by an alien race through wormholes and later returned to his family every ten years.[121] |

| Sliders | In the FOX/Sci-Fi series Sliders, a method is found to create a wormhole that allows travel not between distant points but between different parallel universes;[122][123] objects or people that travel through the wormhole begin and end in the same location geographically (e.g. if one leaves San Francisco, one will arrive in an alternate San Francisco) and chronologically (if it is 1999 at the origin point, so it is at the destination, at least by the currently accepted calendar on our Earth.)[124] Early in the series, the wormhole is referred to by the name "Einstein–Rosen–Podolsky bridge," apparently a merging of the concepts of an Einstein–Rosen bridge and the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox, a thought-experiment in quantum mechanics.[125][self-published source?][126][self-published source?] This series presumes that we exist as part of a multiverse and asks what might have resulted had major or minor events in history occurred differently; the wormholes in the series allow access to the alternate universes in which the series is set. |

| Déjà Vu | The 2006 film Déjà Vu is based on a phenomenon caused by a wormhole, specifically referred to as an Einstein–Rosen Bridge.[127][128] |

| The Lost Room | The Lost Room is a science fiction television miniseries that aired on the Sci Fi Channel in the United States. The main character is allowed to travel around the planet when using a special key together with any kind of door, leading him to random locations. The key is part of a series of different artifacts, coming from an alternate reality.[129][130] |

| Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure | Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure is a 1989 American science fiction–comedy buddy film and the first film in the Bill & Ted franchise in which two metalhead slackers travel through a temporal wormhole in order to assemble a menagerie of historical figures for their high school history presentation.[131][132] |

| Primeval: New World | In the Primeval spin-off series Primeval: New World, Lt. Kenneth Leeds theorizes that the anomalies, the central plot point of the series which allow dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures into the present day, are Einstein–Rosen Bridges after discovering the Spaghetti Junction in the Season 1 finale. However, this seems unlikely since they do not exist within black holes and do not allow travel across distances beyond the Earth yet, only through time.[133][134] |

| Rick and Morty | In the animated show, the main protagonist Rick Sanchez uses what's referred to as a 'portal gun' as a plot device to travel to different universes, dimensions and realities. Despite being described by Adult Swim as its "most scientifically accurate animated comedy", the rules of inter-dimensional travel are usually played for laughs, often spoofing common science fiction tropes and popular culture approaches to the multiverse.[135][136][137] |

| Voltron: Legendary Defender | In the animated show, the main way of travel in space are Wormholes, created by the power of Altean Magic. The show's protagonist use wormholes to escape dangerous situation or to fly away from a fight.[138] |

| Interstellar | In the 2014 film Interstellar, scientists at NASA discover a wormhole orbiting the planet of Saturn, and send a team to travel through it to a distant galaxy in order to find a new home for the human race before Earth is unfit for life. The wormhole takes them halfway across the observable universe to another star system, containing a huge black hole named Gargantua. This new system has three candidate planets for re-seeding the human race, two of which orbit the black hole. In the movie, the wormhole is implied to have been placed there by future humans for the present humans to find a new home. The wormhole is described as the surface of a ball.[139][140][141][142][143] |

| The Flash | In the CW Network Superhero sci-fi, wormholes play a vital role in the series.[144][145][146][147] |

| Strange Days at Blake Holsey High | The television program features a wormhole that can lead to either the future or the past.[148] |

| Futurama | In the final scene of the direct-to-video movie, Into the Wild Green Yonder, the series protagonists travel through a wormhole.[149] The movie also features black holes as part of Leo Wong's golf course.[150] In the episode following the movie, Rebirth, Professor Farnsworth names the wormhole as the Panama Wormhole, after the Panama Canal, calling it as "Earth's central channel for shipping."[151] The characters also travel through a wormhole back to the year 1947 and back to the future in the December 8, 2001, episode, Roswell That Ends Well.[152] |

| Mirakel | In 2020, two Swedish scientists, Vilgot and Anna-Karin, develop an artificial wormhole (also known as an artificial black hole) in an attempt to control the electricity market. It malfunctions and instead causes two girls, Mira in 2020 and Rakel in 1920, to travel through time and swap bodies with each other.[153] |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Taylor Redd, Nola (October 21, 2017). "What is a Wormhole?". Space.com. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Siegfried, Tom (August 19, 2016). "A new 'Einstein' equation suggests wormholes hold key to quantum gravity". Science News. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Einstein, A.; Rosen, N. (July 1, 1935). "The Particle Problem in the General Theory of Relativity". Physical Review. 48 (1): 73–77. Bibcode:1935PhRv...48...73E. doi:10.1103/physrev.48.73. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Maldacena, Juan (2013). "Entanglement and the Geometry of Spacetime". Institute for Advanced Study. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Crothers, Stephen J. (October 3, 2014). "Wormholes and Science Fiction". Thunderbolts Project.

- ^ Grush, Loren (October 26, 2014). "What is a Wormhole and Will Wormhole Travel Ever be Possible?". Popular Science. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Veggeberg, Scott (July 1992). "Cosmic Wormholes: Where Science Meets Science Fiction". The Scientist Magazine. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Grazier, Kevin R.; Cass, Stephen (2015). Hollyweird Science: From Quantum Quirks to the Multiverse. Sylmar, CA and Boston, MA: Springer. p. 234. ISBN 9783319150727.

- ^ Beeler, Stan; Dickson, Lisa (2006). Reading Stargate SG-1. London & New York: I.B.Tauris. p. 259. ISBN 9781845111830.

- ^ Siegel, Ethan (April 22, 2017). "Ask Ethan: What Should A Black Hole's Event Horizon Look Like?". Forbes. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Wheeler, J. Craig (2007). Cosmic Catastrophes: Exploding Stars, Black Holes, and Mapping the Universe (Second ed.). Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 292. ISBN 9781139462419.

- ^ Arnold, Sofia (March 8, 2018). "Somewhere Over the Wormhole: "Farscape" 15 Years Later". Paley Matters. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Guffey, Ensley F. (2013). "War and Peace by Woody Allen or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Wormhole Weapon". In Ginn, Sherry (ed.). The Worlds of Farscape: Essays on the Groundbreaking Television Series. Critical Explorations in Science Fiction and Fantasy. Vol. 40. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland. pp. 22–37. ISBN 9780786467907.

- ^ Shankel, Jason (November 13, 2011). "What are the absolutely essential episodes of Farscape?". io9. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Maher, Ian (1999). "The Outward Voyage and the Inward Search: Star Trek Motion Pictures and the Spiritual Quest". In Porter, Jennifer E.; McLaren, Darcee L. (eds.). Star Trek and Sacred Ground: Explorations of Star Trek, Religion, and American Culture. New York: SUNY Press. p. 166. ISBN 9781438416359.

- ^ a b Okuda, Michael; Okuda, Denise; Mirek, Debbie (1999) [1994]. The Star Trek Encyclopedia. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451646887.

- ^ "The Price". Star Trek: The Next Generation.

- ^ Robinson, Ben; Riley, Marcus; Okuda, Michael (2010). Star Trek: U.S.S. Enterprise Haynes Manual. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 34. ISBN 9781451621297.

- ^ "Bajoran Wormhole". StarTrek.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Reeves-Stevens, Judith; Reeves-Stevens, Garfield (1994). The Making of Star Trek, Deep Space Nine. Pocket Books. p. 62. ISBN 9780671874308.

- ^ Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Encyclopedia. p. 493.

- ^ Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Encyclopedia. p. 371.

- ^ a b Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Encyclopedia. p. 372.

- ^ Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Encyclopedia. p. 462.

- ^ Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Encyclopedia. p. 302.

- ^ Padnick, Steven (July 12, 2012). "In Praise of Red Matter". Tor.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Norma (May 14, 2015). "Rebooting Utopia: Reimagining Star Trek in post-9/11 America". In Brode, Douglas; Brode, Shea T. (eds.). The Star Trek Universe: Franchising the Final Frontier. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 191. ISBN 9781442249868.

- ^ Burk, Graeme; Smith, Robert (2012). Who Is the Doctor: The Unofficial Guide to Doctor Who: The New Series. Toronto: ECW/ORIM. ISBN 9781770902398.

- ^ "Planet of the Dead. 1 Episode, Broadcast: 11th April 2009". The Locations Guide to Doctor Who, Torchwood, and the Sarah Jane Adventures. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ McAlpine, Fraser (February 24, 2017). "'Doctor Who': 10 Things You May Not Know About 'Planet of the Dead'". BBC America. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Waltonen, Karma (2013). "Religion in Doctor Who: Cult Ethics". In Crome, Andrew; McGrath, James F. (eds.). Religion and Doctor Who: Time and Relative Dimensions in Faith. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 154. ISBN 9781630874605.

- ^ Parsons, Paul (2007). The Science of Doctor Who. Cambridge: Icon. pp. 31–47. ISBN 9781840467376.

- ^ Frei, Vincent (June 30, 2011). "THOR: Paul Butterworth – VFX Supervisor & Co-founder – Fuel VFX". The Art of VFX. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Mike; Team, Ohotmu (2017). Marvel Cinematic Universe Guidebook: The Avengers Initiative. Marvel Entertainment. ISBN 9781302496920.

- ^ White, Christopher G. (2018). Other Worlds: Spirituality and the Search for Invisible Dimensions. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press. p. 240. ISBN 9780674984295.

- ^ Brode, Douglas (2015). Fantastic Planets, Forbidden Zones, and Lost Continents: The 100 Greatest Science-Fiction Films. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. p. 361. ISBN 9781477302477.

- ^ Dudenhoeffer, Larrie (2017). Anatomy of the Superhero Film. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9783319579221.

- ^ Alvarado, Sebastian (2019). The Science of Marvel: From Infinity Stones to Iron Man's Armor, the Real Science Behind the MCU Revealed!. New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, New Delhi: Simon and Schuster. p. 175. ISBN 9781507209981.

- ^ Farber, Ryan Jeffrey (2019). Parallel Universes Explained. New York: Enslow Publishing, LLC. p. 15. ISBN 9781978504400.

- ^ Hogg, Trevor (December 28, 2017). "Wormholes & Scrappers: Double Negative Delivers Visual Feast for 'Thor: Ragnarok'". Animation World Network. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Weldon, Glen (April 16, 2018). "Here's What You Need To Know About Infinity Stones Before The New Avengers Movie". NPR.org. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "What is a Wormhole?". Space.com. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Lindley, David (March 25, 2005). "Focus: The Birth of Wormholes". Physics. 15 (1): 11. Bibcode:1935PhRv...48...73E. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.48.73. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Williamson, Jack. "Astounding Stories, March, 1931 by Various". Retrieved September 10, 2018 – via Project Gutenberg.

It's hard to explain without mathematical language. You might say that we are looking through a hole in space. The new force in the meteorite, amplified by the X-rays and the magnetic field, is causing a distortion of space-time coordinates. You know that a gravitational field bends light; the light of a star is deflected in passing the sun. The field of this meteorite bends light through space-time, through the four-dimensional continuum. That scrap of ocean we can see may be on the other side of the earth.

- ^ Stableford, Brian (2006). "Meteorite". Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. New York & London: Routledge. pp. 302. ISBN 9781135923747.

jack williamson the meteor girl.

- ^ Strider, Jessica (July 13, 2012). "BOOK REVIEW: The Forever War by Joe Haldeman". SF Signal. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Brezina, Corona (2019). Time Travel. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 37. ISBN 9781508180487.

- ^ Thorne, Kip (1997). "Do the Laws of Physics Permit Wormholes for Interstellar Travel and Machines for Time Travel?". In Terzian, Yervant; Bilson, Elizabeth (eds.). Carl Sagan's Universe. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. pp. 121. ISBN 9780521576031.

contact wormholes carl sagan.

- ^ Whiteside, Martin. "Black Holes and Einstein Rosen Bridges". www.st-v-sw.net. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1985). "Author's Note". Contact. New York, London Toronto, Sydney, New Delhi: Simon and Schuster. p. 373. ISBN 9781501197987.

- ^ Wall, Mike (November 24, 2014). "'Interstellar' Science: Is Wormhole Travel Possible?". Space.com. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Petersen, Carolyn Collins (2013). Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe. New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, New Delhi: Simon and Schuster. p. 155. ISBN 9781440563591.

- ^ Bujold, Lois McMaster (2008). Stewart Carl, Lilian; Helfers, John (eds.). The Vorkosigan Companion. Riverdale, NY: Baen Publishing Enterprises. ISBN 9781618247063.

- ^ Cowie, Jonathan. "Review of Xeelee Vengeance by Stephen Baxter". www.concatenation.org. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Esomba, Steve (2013). Moving Cameras and Living Movies. Morisville, NC: Lulu.com. p. 207. ISBN 9781291351576.[self-published source]

- ^ Weber, David (2013). House of Steel: The Honorverse Companion. Riverdale, NY: Baen Publishing Enterprises. ISBN 9781625790989.

- ^ Gresh, Lois H. (October 30, 2007). Exploring Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials: An Unauthorized Adventure Through The Golden Compass, The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass. New York: St. Martin's Press / Macmillan. p. 201. ISBN 9780312347437.

Wormhole. Multiply connected spaces, passages between universes. It's unknown at this time whether mass can travel through a wormhole without being destabilized or destroyed.

- ^ Cousin, Geraldine (July 19, 2013). Playing for time: Stories of lost children, ghosts and the endangered present in contemporary theatre. Manchester University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9781847795489 – via Google Books.

The windows in His Dark Materials are the equivalent of wormholes, and Lyra and Will use them to journey between parallel worlds.

- ^ Nahin, Paul J. (December 24, 2016). Time Machine Tales: The Science Fiction Adventures and Philosophical Puzzles of Time Travel. Springer. p. 84. ISBN 9783319488646 – via Google Books.

The general theory of relativity predicts the existence of wormholes in spacetime and, in fact, they were first 'discovered' theoretically in the mathematics of relativity as early as 1916 by the Viennese physicist Ludwig Flamm (1885-1964). Later analyses were done by Einstein, himself. Wormholes have been discussed as a possible model for pulsars (as opposed to the more usual model as rotating neutron stars). It has also been suggested that the interior of a charged black hole may be the entrance to a wormhole. All of these various solutions to the gravitational field equations are generically called 'Einstein-Rosen bridges' in the physics literature (see note 81 for example), and the term soon appeared in fiction, too. [Note 83: See, for example, J. G. Cramer, Einstein's Bridge, Avon 1977]

- ^ Halpern, Paul (2009). Collider: The Search for the World's Smallest Particles. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 222. ISBN 9780470286203.

Cramer Einstein's Bridge wormhole.

- ^ Cramer, John G. (March 8, 2008). "All About Teleportation". Analog Science Fiction & Fact. July / August 2008 – via Center for Experimental Nuclear Physics and Astrophysics (CENPA) - University of Washington.

- ^ Wolf, Mark J. P. (2012). Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation. New York and London: Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 9781136220807.

In his novel Diaspora (1998), Greg Egan invents new theories of physics including Kozuch Theory, which views elementary particles as six-dimensional wormholes

- ^ Egan, Greg (February 26, 2008). "Chapter 9: Degrees of Freedom - Wormholes in Kozuch Theory". www.gregegan.net. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Grazier, Kevin Robert; Grazier, Robert (2008). The Science of Michael Crichton: An Unauthorized Exploration Into the Real Science Behind the Fictional Worlds of Michael Crichton. Dallas, TX: BenBella Books. pp. 94–95. ISBN 9781933771328.

- ^ Blanch, Robert J. (2000). "Timeline by Michael Crichton (review)". Arthuriana. 10 (4): 69–71. doi:10.1353/art.2000.0038. ISSN 1934-1539. S2CID 160339886.

- ^ Stableford, Brian (2006). Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. New York and London: Routledge. pp. 66. ISBN 9781135923747.

the light of other days wormhole.

- ^ Mead, David G.; Frelik, Paweł (2007). Playing the Universe: Games and Gaming in Science Fiction. Lublin, Poland: Maria Curie-Skłodowska University. p. 33. ISBN 9788322726563.

- ^ Atherton, Kate (September 26, 2014). "10 Reasons to Read and Love Peter F. Hamilton". Tor.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Stableford, Brian (2006). Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. New York & London: Routledge. pp. 66. ISBN 9781135923747.

the algebraist wormholes.

- ^ Sourbut, Elizabeth (December 8, 2004). "Four new tales in science fiction". New Scientist. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ McKie, Andrew (November 9, 2004). "When wormholes collapse: Andrew McKie reviews The Algebraist by Iain M Banks". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Hartland, Dan (May 12, 2008). "House of Suns by Alastair Reynolds". Strange Horizons (12 May 2008).

- ^ 2010 Hugo Award Winners at TheHugoAwards.org, published September 5, 2010, retrieved May 29, 2011

- ^ "Palimpsest". Publishers Weekly. August 1, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Escape Pod, Ep. 421". escapepod.org (Podcast). Escape Artists. November 10, 2013.

- ^ Chen, Colleen (August 14, 2011). "Fantasy & Science Fiction -- Sept./Oct. 2011". www.tangentonline.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Corey, James S.A (2013). Abaddon's Gate. Orbit Books. ISBN 978-0-316-12907-7.

- ^ Damico, Gina (April 17, 2017). "Waste of Spce". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Bush, Elizabeth (June 24, 2017). "Waste of Space by Gina Damico (review)". Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books. 70 (11): 483–484. doi:10.1353/bcc.2017.0483. ISSN 1558-6766. S2CID 201712068.

- ^ McParland, Robert (2018). Myth and Magic in Heavy Metal Music. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 184. ISBN 9781476673356.

- ^ Cohen, Johathan. "Update: Mastodon To Play Complete 'Skye' On North American Tour". Billboard. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

It's about a crippled young man who experiments with astral travel. He goes up into outer space, goes too close to the sun, gets his golden umbilical cord burned off, flies into a wormhole, is thrust into the spirit real, has conversations with spirits about the fact that he's not really dead, and they decide to help him.

- ^ McPadden, Mike (May 1, 2012). If You Like Metallica...: Here Are Over 200 Bands, CDs, Movies, and Other Oddities That You Will Love. Backbeat Books. ISBN 9781476813578.

Two thousand nine's Crack the Skye concerns the time-space wormhole travels of an astral-projecting paraplegic who enters Rasputin's body to battle the devil.

- ^ Cox, Caleb (February 9, 2012). "Life-size Portal gun to shoot onto shelves soon". The Register. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Ryan J. (2017). Screen Savvy: Creating Balance in a Digital World. Springville, UT: Cedar Fort. ISBN 9781462128471.

- ^ Jones, Steven E. (2014). The Emergence of the Digital Humanities. New York and London: Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 9781136202353.

- ^ Guerra, Bob (December 1989). "Space Rogue". Compute!. No. 115. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Doug, Radcliffe (2003). Freelancer: Sybex Official Strategies & Secrets. Alameda, CA: SYBEX. ISBN 0782141870. OCLC 50841933.

- ^ Desslock (March 4, 2003). "Freelancer: While it's not the revolutionary title it initially promised to be, Freelancer delivers the exact combination of addictive and accessible gameplay that the genre has needed for a long time". Game Spot.

- ^ Misund Berntsen, Andreas (November 5, 2005). "Darkspace Review". www.gamershell.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Getchell, Adam (January 14, 2006). "Wormhole Engineering in Orion's Arm: An Overview" (PDF). Orion's Arm Universe Project.

- ^ "Wormhole Nexus, The". Orion's Arm - Encyclopedia Galactica. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Tringham, Neal Roger (2015). Science Fiction Video Games. Boca Raton, FL, London and New York: CRC Press. p. 437. ISBN 9781482203899.

- ^ Purchese, Robert (October 21, 1999). "X: Beyond The Frontier - Another futile attempt to recreate Elite falls flat on its face". Eurogamer. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Rorie, Matthew (April 3, 2009). "Metroid Prime 3: Corruption Walkthrough". GameSpot. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Knight, David (2007). "Walkthrough". Metroid Prime 3: Corruption Premiere Edition. Roseville, CA: Prima Games. pp. 20–210. ISBN 978-0-7615-5642-8.

- ^ DNM (January 15, 2001). "Far Gate: Review - can Far Gate boldly go where Homeworld has gone before?". Eurogamer. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Todd, Brett (May 17, 2006). "Far Gate Review: In spite of the game's original qualities, there are just too many other, better choices available to make it worthwhile for most real-time strategy game players". GameSpot. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Umbra Shepard (August 13, 2012), Star Trek: Shattered Universe Walkthrough Mission 16: "Wormhole" (Cheat), archived from the original on December 21, 2021, retrieved March 10, 2019

- ^ Tringham, Neal Roger (2015). Science Fiction Video Games. Boca Raton, FL, London and New York: CRC Press. p. 257. ISBN 9781482203899.

- ^ "Gods And Monsters". IGN.com. March 2, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Stargates - Real Life Science Fiction". EVE Fiction. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Warmelink, Harald (2010). "Born Again in a Fictional Universe: A Participant Portrait of EVE Online". In Urbanski, Heather (ed.). Writing and the Digital Generation: Essays on New Media Rhetoric. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland. p. 201. ISBN 9780786455867.

- ^ Capslock, CCP (March 10, 2009). "Patch Notes for Apocrypha". EVE Online. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Abathur, CCP (March 5, 2009). "The Darkness at the End of the Tunnel". EVE Online. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Khaw, Cassandra (July 16, 2013). "Into the Wormhole: An afternoon with EVE Online's least understood demographic". PCWorld. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Rossignol, Jim (March 14, 2009). "Stranded Beyond The Wormhole". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Cox, Matt (November 3, 2017). "Stellaris FTL changes are in the warp pipes". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Apolon (December 24, 2017). "Stellaris: The Biggest Changes Coming In The Cherryh Update". Player.One. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Command & Conquer 3: Tiberium Wars - Scrin Rift, archived from the original on December 21, 2021, retrieved September 28, 2019

- ^ Perlin, Michael (2015). Fantastic Adventures in Metaphysics. Huntsville, AR: Ozark Mountain Publishing.

- ^ "The Triangle (2005)". Moria. December 10, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Invader Zim, Season 1". www.quotes.net. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Episode Guide - Season 1, Episode 7 A Room with a Moose; Hamstergeddon". TVGuide.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Phillips, Cynthia; Priwer, Shana (2009). Space Exploration For Dummies®. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 340. ISBN 9780470549742.

Event Horizon 1997 wormhole.

- ^ McCarter, Reid (July 25, 2018). "Is Event Horizon actually disturbing or are we just scared of an angry Sam Neill?". News. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Eddy, Cheryl (April 2, 2015). "All The Reasons Why Event Horizon Is A Hell Of A Good Time". io9. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Grazier, Kevin R.; Cass, Stephen (2015). Hollyweird Science: From Quantum Quirks to the Multiverse. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 234. ISBN 9783319150727.

- ^ Capps, Robert (April 1, 2010). "As the Wormhole Turns: Fringe Flashes Back to Parallel Universe". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane (May 7, 2011). "Fringe finally sums up the central paradox of Walter Bishop, the gentle destroyer". io9. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Sherman, Fraser A. (2017). Now and Then We Time Travel: Visiting Pasts and Futures in Film and Television. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 188–189. ISBN 9780786496792.

- ^ Garcia, Frank; Phillips, Mark (2009). Science Fiction Television Series, 1990-2004: Histories, Casts and Credits for 58 Shows. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland. p. 381. ISBN 9780786469178.

- ^ Jones, Marie D.; Flaxman, Larry (2012). This Book is From the Future: A Journey Through Portals, Relativity, Worm Holes, and Other Adventures in Time Travel. Pompton Plains, NJ: Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 9781601635808.

- ^ Johnson-Smith, Jan (2005). American Science Fiction Tv: Star Trek, Stargate and Beyond. London and New York: I.B.Tauris. pp. 160–161. ISBN 9781860648823.

sliders wormhole.

- ^ Wheeler, J. Craig (2007). Cosmic Catastrophes: Exploding Stars, Black Holes, and Mapping the Universe. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 292. ISBN 9781139462419.

- ^ Chance, Norman (2011). Who was Who on TV. Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris Corporation. p. 221. ISBN 9781456824563.[self-published source]

- ^ Massicot, Jean (2011). Notions fondamentales de physique (in French). Morisville, NC: Lulu.com. p. 466. ISBN 9781445298559.[self-published source]

- ^ Sherman, Fraser A. (2017). Now and Then We Time Travel: Visiting Pasts and Futures in Film and Television. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 191. ISBN 9780786496792.

- ^ Fahy, Declan (2015). "The Charming Stardom of Brian Greene". The New Celebrity Scientists: Out of the Lab and into the Limelight. Lanham, MA, Boulder, CO, New York, London: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 170. ISBN 9781442233430.

- ^ Abbott, Stacey; Lavery, David (2011). TV Goes to Hell: An Unofficial Road Map of Supernatural. Toronto: ECW Press. p. 274. ISBN 9781770900349.

- ^ Lizowski, James (January 7, 2017). "Most Underrated Sci-Fi TV Shows". FUTURISM. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Mowbray, Scott (March 2002). "Let's Do the Time Warp Again". Popular Science. Vol. 260, no. 3. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Siegfried, Tom (August 5, 2013). "Long the stuff of fantasy, wormholes may be coming soon to a telescope near you". Science News. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Keene, Allison (June 8, 2013). "'Sinbad' and 'Primeval: New World': TV Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Wiegand, David (June 6, 2013). "'Sinbad,' 'Primeval' reviews: Good, bad - SFChronicle.com". www.sfgate.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Abesamis, Lester C. (2019). "Neither the Hero You Deserve or the Hero You Need". In Abesamis, Lester C.; Yuen, Wayne (eds.). Rick and Morty and Philosophy: In the Beginning Was the Squanch. Chicago, IL: Open Court Publishing. ISBN 9780812694666.

- ^ Kim, Meeri (July 28, 2017). "Rick and Morty Gets Multiverse Theory Totally Wrong, but Physicists Don't Care". Slate Magazine. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ For Us Nerds (August 14, 2017). "Why Rick and Morty Doesn't Bother With Time Travel (Mostly)". For Us Nerds. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Anderson, Kyle (January 20, 2017). "VOLTRON Recap: "Across the Universe" and Lost in Space". Nerdist. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ Thorne, Kip (2014). The Science of Interstellar. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393351385.

- ^ Wall, Mike (November 10, 2014). "The Science of 'Interstellar': Black Holes, Wormholes and Space Travel". Space.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Knapton, Sarah (November 17, 2015). "The science of Interstellar: fact or fiction?". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ The Physics arXiv Blog (February 20, 2016). "Why Hollywood had To Fudge The Relativity-Based Wormhole Scenes in Interstellar". Medium. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Nugent, John (April 21, 2016). "Movie plots explained: Interstellar". Empire. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Hayner, Chris E. (May 20, 2015). "'The Flash' Season 1 finale: Whose helmet came through the wormhole?". Screener. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Panos, Maggie (May 20, 2015). "The 1 Detail From The Flash's Finale That You May Have Missed". PopSugar. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ Rullo, Sam (May 20, 2015). "Will Barry Die On 'The Flash'? The Singularity Wormhole In "Fast Enough" Threatens The Entire World". Bustle. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Dyce, Andrew (October 26, 2016). "The Real Science of Flash's Mirror Master Explained". ScreenRant. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Strange Days at Blake Holsey High - Season 1, Episode 1 Wormhole". TVGuide.com. October 5, 2002. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Turfrey, Louis (January 12, 2009). "Futurama: Into the Wild Green Yonder Blu-ray review". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Kauffman, Jeffrey (March 1, 2009). "Futurama: Into the Wild Green Yonder (Blu-ray)". DVD-Talk. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ "Futurama Recap - Rebirth". Syfy. January 12, 2009. Archived from the original on June 2, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ "Futurama Recap - Roswell That Ends Well". Syfy. January 12, 2009. Archived from the original on March 7, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ "Årets julkalender: En tidsresa till 1920". Sveriges Television. January 29, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

Further reading

edit- Langford, David (2016). "Wormholes". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- Westfahl, Gary (2021). "Wormholes". Science Fiction Literature through History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 709–711. ISBN 978-1-4408-6617-3.