Spiritualism is a social religious movement popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, according to which an individual's awareness persists after death and may be contacted by the living.[1] The afterlife, or the "spirit world", is seen by spiritualists not as a static place, but as one in which spirits continue to interact and evolve. These two beliefs—that contact with spirits is possible, and that spirits are more advanced than humans—lead spiritualists to the belief that spirits are capable of advising the living on moral and ethical issues and the nature of God. Some spiritualists follow "spirit guides"—specific spirits relied upon for spiritual direction.[2][3]

Emanuel Swedenborg has some claim to be the father of spiritualism.[4] The movement developed and reached its largest following from the 1840s to the 1920s, especially in English-speaking countries.[3][5] It flourished for a half century without canonical texts or formal organization, attaining cohesion through periodicals, tours by trance lecturers, camp meetings, and the missionary activities of accomplished mediums. Many prominent spiritualists were women, and like most spiritualists, supported causes such as the abolition of slavery and women's suffrage.[3] By the late 1880s the credibility of the informal movement had weakened due to accusations of fraud perpetrated by mediums, and formal spiritualist organizations began to appear.[3] Spiritualism is currently practiced primarily through various denominational spiritualist churches in the U.S., Canada and the United Kingdom.

Beliefs

editMediumship and spirits

editSpiritualists believe in the possibility of communication with the spirits of dead people, whom they regard as "discarnate humans". They believe that spirit mediums are gifted to carry on such communication, but that anyone may become a medium through study and practice. They believe that spirits are capable of growth and perfection, progressing through higher spheres or planes, and that the afterlife is not a static state, but one in which spirits evolve. The two beliefs—that contact with spirits is possible, and that spirits may dwell on a higher plane—lead to a third belief, that spirits can provide knowledge about moral and ethical issues, as well as about God and the afterlife. Many believers therefore speak of "spirit guides"—specific spirits, often contacted, and relied upon for worldly and spiritual guidance.[2][3]

According to spiritualists, anyone may receive spirit messages, but formal communication sessions (séances) are held by mediums, who claim thereby to receive information about the afterlife.[2]

Declaration of Principles

editAs an informal movement, spiritualism does not have a defined set of rules, but various spiritualist organizations within the United States have adopted variations on some or all of a "Declaration of Principles" developed between 1899 and 1944. In October 1899, a six article "Declaration of Principles" was adopted by the National Spiritualist Association (NSA) at a convention in Chicago, Illinois.[6] An additional two principles were added by the NSA in October 1909, at a convention in Rochester, New York.[7] Then, in October 1944, a ninth principle was adopted by the National Spiritualist Association of Churches, at a convention in St. Louis, Missouri.[citation needed]

In the UK, the main organization representing spiritualism is the Spiritualists' National Union (SNU), whose teachings are based on the Seven Principles.[8]

Origins

editSpiritualism first appeared in the 1840s in the "Burned-over District" of upstate New York, where earlier religious movements such as Millerism and Mormonism had emerged during the Second Great Awakening, although Millerism and Mormonism did not associate themselves with spiritualism.

This region of New York State was an environment in which many thought direct communication with God or angels was possible, and that God would not behave harshly—for example, that God would not condemn unbaptised infants to an eternity in Hell.[2]

Swedenborg and Mesmer

editIn this environment, the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) and the teachings of Franz Mesmer (1734–1815) provided an example for those seeking direct personal knowledge of the afterlife. Swedenborg, who claimed to communicate with spirits while awake, described the structure of the spirit world. Two features of his view particularly resonated with the early spiritualists: first, that there is not a single Hell and a single Heaven, but rather a series of higher and lower heavens and hells; second, that spirits are intermediates between God and humans, so that the divine sometimes uses them as a means of communication.[2] Although Swedenborg warned against seeking out spirit contact, his works seem to have inspired in others the desire to do so.

Swedenborg was formerly a highly regarded inventor and scientist, achieving several engineering innovations and studying physiology and anatomy. Then, "in 1741, he also began to have a series of intense mystical experiences, dreams, and visions, claiming that he had been called by God to reform Christianity and introduce a new church."[9]

Mesmer did not contribute religious beliefs, but he brought a technique, later known as hypnotism, that it was claimed could induce trances and cause subjects to report contact with supernatural beings. There was a great deal of professional showmanship inherent to demonstrations of Mesmerism, and the practitioners who lectured in mid-19th-century North America sought to entertain their audiences as well as to demonstrate methods for personal contact with the divine.[2]

Perhaps the best known of those who combined Swedenborg and Mesmer in a peculiarly North American synthesis was Andrew Jackson Davis, who called his system the "harmonial philosophy". Davis was a practising Mesmerist, faith healer and clairvoyant from Blooming Grove, New York. He was also strongly influenced by the socialist theories of Fourierism.[10] His 1847 book, The Principles of Nature, Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind,[11] dictated to a friend while in a trance state, eventually became the nearest thing to a canonical work in a spiritualist movement whose extreme individualism precluded the development of a single coherent worldview.[2][3]

-

Andrew Jackson Davis, about 1860

Reform-movement links

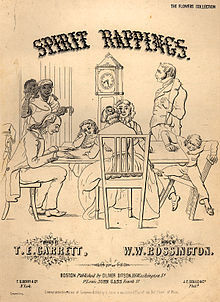

editSpiritualists often set March 31, 1848, as the beginning of their movement. On that date, Kate and Margaret Fox, of Hydesville, New York, reported that they had made contact with a spirit that was later claimed to be the spirit of a murdered peddler whose body was found in the house, though no record of such a person was ever found. The spirit was said to have communicated through rapping noises, audible to onlookers. The evidence of the senses appealed to practically minded Americans, and the Fox sisters became a sensation. As the first celebrity mediums, the sisters quickly became famous for their public séances in New York.[12] However, in 1888 the Fox sisters admitted that this contact with the spirit was a hoax, though shortly afterward they recanted that admission.[2][3]

Amy and Isaac Post, Hicksite Quakers from Rochester, New York, had long been acquainted with the Fox family, and took the two girls into their home in the late spring of 1848. Immediately convinced of the veracity of the sisters' communications, they became early converts and introduced the young mediums to their circle of radical Quaker friends.[13]

Consequently, many early participants in spiritualism were radical Quakers and others involved in the mid-nineteenth-century reforming movement. These reformers were uncomfortable with the more mainstream churches because those churches did little to fight slavery and even less to advance the cause of women's rights.[3]

Such links with reform movements, often radically socialist, had already been prepared in the 1840s, as the example of Andrew Jackson Davis shows. After 1848, many socialists became ardent spiritualists or occultists.[14]

The most popular trance lecturer prior to the American Civil War was Cora L. V. Scott (1840–1923). Young and beautiful, her appearance on stage fascinated men. Her audiences were struck by the contrast between her physical girlishness and the eloquence with which she spoke of spiritual matters, and found in that contrast support for the notion that spirits were speaking through her. Cora married four times, and on each occasion adopted her husband's last name. During her period of greatest activity, she was known as Cora Hatch.[3]

Another spiritualist was Achsa W. Sprague, who was born November 17, 1827, in Plymouth Notch, Vermont. At the age of 20, she became ill with rheumatic fever and credited her eventual recovery to intercession by spirits. An extremely popular trance lecturer, she traveled about the United States until her death in 1861. Sprague was an abolitionist and an advocate of women's rights.[3]

Another spiritualist and trance medium prior to the Civil War was Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825–1875), a man of mixed race, who also played a part in the abolitionist movement.[15] Nevertheless, many abolitionists and reformers held themselves aloof from the spiritualist movement; among the skeptics was abolitionist Frederick Douglass.[16]

Another social reform movement with significant spiritualist involvement was the effort to improve conditions of Native Americans. Kathryn Troy writes in a study of Indian ghosts in seances:

Undoubtedly, on some level spiritualists recognized the Indian spectres that appeared at seances as a symbol of the sins and subsequent guilt of the United States in its dealings with Native Americans. Spiritualists were literally haunted by the presence of Indians. But for many that guilt was not assuaged: rather, in order to confront the haunting and rectify it, they were galvanized into action. The political activism of spiritualists on behalf of Indians was thus the result of combining white guilt and fear of divine judgment with a new sense of purpose and responsibility.[17]

Believers and skeptics

editIn the years following the sensation that greeted the Fox sisters, demonstrations of mediumship (séances and automatic writing, for example) proved to be a profitable venture, and soon became popular forms of entertainment and spiritual catharsis. The Fox sisters earned a living this way and others followed their lead.[2][3] Showmanship became an increasingly important part of spiritualism, and the visible, audible, and tangible evidence of spirits escalated as mediums competed for paying audiences. As independent investigating commissions repeatedly established, most notably the 1887 report of the Seybert Commission,[18] fraud was widespread, and some of these cases were prosecuted in the courts.[19]

Despite numerous instances of chicanery, the appeal of spiritualism was strong. Prominent in the ranks of its adherents were those grieving the death of a loved one. Many families during the time of the American Civil War had seen their men go off and never return, and images of the battlefield, produced through the new medium of photography, demonstrated that their loved ones had not only died in overwhelmingly huge numbers, but horribly as well. One well known case is that of Mary Todd Lincoln who, grieving the loss of her son, organized séances in the White House which were attended by her husband, President Abraham Lincoln.[16] The surge of Spiritualism during this time, and later during World War I, was a direct response to those massive battlefield casualties.[20]

In addition, the movement appealed to reformers, who fortuitously found that the spirits favoured such causes du jour as abolition of slavery, and equal rights for women.[3] It also appealed to some who had a materialist orientation and rejected organized religion. In 1854 the utopian socialist Robert Owen was converted to spiritualism after "sittings" with the American medium Maria B. Hayden (credited with introducing spiritualism to England); Owen made a public profession of his new faith in his publication The Rational Quarterly Review and later wrote a pamphlet, "The future of the Human race; or great glorious and future revolution to be effected through the agency of departed spirits of good and superior men and women".[21]

-

Frank Podmore, c. 1895

-

William Crookes. Photo published 1904.

-

Harry Price, 1922

A number of scientists who investigated the phenomenon also became converts. They included chemist and physicist William Crookes (1832–1919),[citation needed] evolutionary biologist Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913)[22][third-party source needed] and physicist Sir Oliver Lodge.[citation needed] Nobel laureate Pierre Curie was impressed by the mediumistic performances of Eusapia Palladino and advocated their scientific study.[23] Other prominent adherents included journalist and pacifist William T. Stead (1849–1912)[24] and physician and author Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930).[20]

Doyle, who lost his son Kingsley in World War I, was also a member of the Ghost Club. Founded in London in 1862, its focus was the scientific study of alleged paranormal activities in order to prove (or refute) the existence of paranormal phenomena. Members of the club included Charles Dickens, Sir William Crookes, Sir William F. Barrett, and Harry Price.[25] The Paris séances of Eusapia Palladino were attended by an enthusiastic Pierre Curie and a dubious Marie Curie. Thomas Edison wanted to develop a "spirit phone", an ethereal device that would summon to the living the voices of the dead and record them for posterity.[26]

The claims of spiritualists and others as to the reality of spirits were investigated by the Society for Psychical Research, founded in London in 1882. The society set up a Committee on Haunted Houses.[27]

Prominent investigators who exposed cases of fraud came from a variety of backgrounds, including professional researchers such as Frank Podmore of the Society for Psychical Research and Harry Price of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research, and professional conjurers such as John Nevil Maskelyne. Maskelyne exposed the Davenport brothers by appearing in the audience during their shows and explaining how the trick was done.

The psychical researcher Hereward Carrington exposed fraudulent mediums' tricks, such as those used in slate-writing, table-turning, trumpet mediumship, materializations, sealed-letter reading, and spirit photography.[28] The skeptic Joseph McCabe, in his book Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud? (1920), documented many fraudulent mediums and their tricks.[29]

Magicians and writers on magic have a long history of exposing the fraudulent methods of mediumship. During the 1920s, professional magician Harry Houdini undertook a well-publicised campaign to expose fraudulent mediums; he was adamant that "Up to the present time everything that I have investigated has been the result of deluded brains."[30] Other magician or magic-author debunkers of spiritualist mediumship have included Chung Ling Soo,[31] Henry Evans,[32] Julien Proskauer,[33] Fulton Oursler,[34] Joseph Dunninger,[35] and Joseph Rinn.[36]

In February 1921 Thomas Lynn Bradford, in an experiment designed to ascertain the existence of an afterlife, committed suicide in his apartment by blowing out the pilot light on his heater and turning on the gas. After that date, no further communication from him was received by an associate whom he had recruited for the purpose.[37]

Unorganized movement

editThe movement quickly spread throughout the world; though only in the United Kingdom did it become as widespread as in the United States.[5] Spiritualist organizations were formed in America and Europe, such as the London Spiritualist Alliance, which published a newspaper called The Light, featuring articles such as "Evenings at Home in Spiritual Séance", "Ghosts in Africa" and "Chronicles of Spirit Photography", advertisements for "mesmerists" and patent medicines, and letters from readers about personal contact with ghosts.[38] In Britain, by 1853, invitations to tea among the prosperous and fashionable often included table-turning, a type of séance in which spirits were said to communicate with people seated around a table by tilting and rotating the table. By 1897, spiritualism was said to have more than eight million followers in the United States and Europe,[39] mostly drawn from the middle and upper classes.

Spiritualism was mainly a middle- and upper-class movement, and especially popular with women. American spiritualists would meet in private homes for séances, at lecture halls for trance lectures, at state or national conventions, and at summer camps attended by thousands. Among the most significant of the camp meetings were Camp Etna, in Etna, Maine; Onset Bay Grove, in Onset, Massachusetts; Lily Dale, in western New York State;[40] Camp Chesterfield, in Indiana; the Wonewoc Spiritualist Camp, in Wonewoc, Wisconsin; and Lake Pleasant, in Montague, Massachusetts. In founding camp meetings, the spiritualists appropriated a form developed by U.S. Protestant denominations in the early nineteenth century. Spiritualist camp meetings were located most densely in New England, but were also established across the upper Midwest. Cassadaga, Florida, is the most notable spiritualist camp meeting in the southern states.[2][3][41]

A number of spiritualist periodicals appeared in the nineteenth century, and these did much to hold the movement together. Among the most important were the weeklies the Banner of Light (Boston), the Religio-Philosophical Journal (Chicago), Mind and Matter (Philadelphia), the Spiritualist (London), and the Medium (London). Other influential periodicals were the Revue Spirite (France), Le Messager (Belgium), Annali dello Spiritismo (Italy), El Criterio Espiritista (Spain), and the Harbinger of Light (Australia). By 1880, there were about three dozen monthly spiritualist periodicals published around the world.[42] These periodicals differed a great deal from one another, reflecting the great differences among spiritualists. Some, such as the British Spiritual Magazine were Christian and conservative, openly rejecting the reform currents so strong within spiritualism. Others, such as Human Nature, were pointedly non-Christian and supportive of socialism and reform efforts. Still others, such as the Spiritualist, attempted to view spiritualist phenomena from a scientific perspective, eschewing discussion on both theological and reform issues.[43]

Books on the supernatural were published for the growing middle class, such as 1852's Mysteries, by Charles Elliott, which contains "sketches of spirits and spiritual things", including accounts of the Salem witch trials, the Lane ghost, and the Rochester rappings.[44] The Night Side of Nature, by Catherine Crowe, published in 1853, provided definitions and accounts of wraiths, doppelgängers, apparitions and haunted houses.[45]

Mainstream newspapers treated stories of ghosts and haunting as they would any other news story. An account in the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1891, "sufficiently bloody to suit the most fastidious taste", tells of a house believed to be haunted by the ghosts of three murder victims seeking revenge against their killer's son, who was eventually driven insane.

Many families, "having no faith in ghosts", thereafter moved into the house, but all soon moved out again.[46]

In the 1920s many "psychic" books were published of varied quality. Such books were often based on excursions initiated by the use of Ouija boards. A few of these popular books displayed unorganized spiritualism, though most were less insightful.[47]

The movement was extremely individualistic, with each person relying on his or her own experiences and reading to discern the nature of the afterlife. Organisation was therefore slow to appear, and when it did it was resisted by mediums and trance lecturers. Most members were content to attend Christian churches, and particularly universalist churches harboured many spiritualists.

As the spiritualism movement began to fade, partly through the publicity of fraud accusations and partly through the appeal of religious movements such as Christian science, the Spiritualist Church was organised. This church can claim to be the main vestige of the movement left today in the United States.[2][3]

Other mediums

editLondon-born Emma Hardinge Britten (1823–99) moved to the United States in 1855 and was active in spiritualist circles as a trance lecturer and organiser. She is best known as a chronicler of the movement's spread, especially in her 1884 Nineteenth Century Miracles: Spirits and Their Work in Every Country of the Earth, and her 1870 Modern American Spiritualism, a detailed account of claims and investigations of mediumship beginning with the earliest days of the movement.

William Stainton Moses (1839–92) was an Anglican clergyman who, in the period from 1872 to 1883, filled 24 notebooks with automatic writing, much of which was said to describe conditions in the spirit world. However, Frank Podmore was skeptical of his alleged ability to communicate with spirits and Joseph McCabe described Moses as a "deliberate impostor", suggesting his apports and all of his feats were the result of trickery.[48][49]

Eusapia Palladino (1854–1918) was an Italian spiritualist medium from the slums of Naples who made a career touring Italy, France, Germany, Britain, the United States, Russia and Poland. Palladino was said by believers to perform spiritualist phenomena in the dark: levitating tables, producing apports, and materializing spirits. On investigation, all these things were found to be products of trickery.[50][51]

The British medium William Eglinton (1857–1933) claimed to perform spiritualist phenomena such as movement of objects and materializations. All of his feats were exposed as tricks.[52][53]

The Bangs Sisters, Mary "May" E. Bangs (1862–1917) and Elizabeth "Lizzie" Snow Bangs (1859–1920), were two spiritualist mediums based in Chicago, who made a career out of painting the dead or "spirit portraits".

Mina Crandon (1888–1941), a spiritualist medium in the 1920s, was known for producing an ectoplasm hand during her séances. The hand was later exposed as a trick when biologists found it to be made from a piece of carved animal liver.[54] In 1934, the psychical researcher Walter Franklin Prince described the Crandon case as "the most ingenious, persistent, and fantastic complex of fraud in the history of psychic research."[55]

The American voice medium Etta Wriedt (1859–1942) was exposed as a fraud by the physicist Kristian Birkeland when he discovered that the noises produced by her trumpet were caused by chemical explosions induced by potassium and water and in other cases by lycopodium powder.[56]

Another well-known medium was the Scottish materialization medium Helen Duncan (1897–1956). In 1928 photographer Harvey Metcalfe attended a series of séances at Duncan's house and took flash photographs of Duncan and her alleged "materialization" spirits, including her spirit guide "Peggy".[57] The photographs revealed the "spirits" to have been fraudulently produced, using dolls made from painted papier-mâché masks, draped in old sheets.[58] Duncan was later tested by Harry Price at the National Laboratory of Psychical Research; photographs revealed Duncan's ectoplasm to be made from cheesecloth, rubber gloves, and cut-out heads from magazine covers.[59][60]

Evolution

editSpiritualists reacted with an uncertainty to the theories of evolution in the late 19th and early 20th century. Broadly speaking the concept of evolution fitted the spiritualist thought of the progressive development of humanity. At the same time, however, the belief in the animal origins of humanity threatened the foundation of the immortality of the spirit, for if humans had not been created by God, it was scarcely plausible that they would be specially endowed with spirits. This led to spiritualists embracing spiritual evolution.[61]

The spiritualists' view of evolution did not stop at death. Spiritualism taught that after death spirits progressed to spiritual states in new spheres of existence. According to spiritualists, evolution occurred in the spirit world "at a rate more rapid and under conditions more favourable to growth" than encountered on earth.[62]

In a talk at the London Spiritualist Alliance, John Page Hopps (1834–1911) supported both evolution and spiritualism. Hopps claimed humanity had started off imperfect "out of the animal's darkness" but would rise into the "angel's marvellous light". Hopps claimed humans were not fallen but rising creatures and that after death they would evolve on a number of spheres of existence to perfection.[62]

Theosophy is in opposition to the spiritualist interpretation of evolution. Theosophy teaches a metaphysical theory of evolution mixed with human devolution. Spiritualists do not accept the devolution of the theosophists. To theosophy, humanity starts in a state of perfection (see Golden age) and falls into a process of progressive materialization (devolution), developing the mind and losing the spiritual consciousness. After the gathering of experience and growth through repeated reincarnations humanity will regain the original spiritual state, which is now one of self-conscious perfection.

Theosophy and spiritualism were both very popular metaphysical schools of thought especially in the early 20th century and thus were always clashing in their different beliefs. Madame Blavatsky was critical of spiritualism; she distanced theosophy from spiritualism as far as she could and allied herself with eastern occultism.[63]

One medium who rejected evolution was Cora L. V. Scott; she dismissed evolution in her lectures and instead supported a type of pantheistic spiritualism.[64] The spiritualist Gerald Massey wrote that Darwin's theory of evolution was incomplete.[65]

Alfred Russel Wallace believed qualitative novelties could arise through the process of spiritual evolution, in particular the phenomena of life and mind. Wallace attributed these novelties to a supernatural agency.[66] Later in his life, Wallace was an advocate of spiritualism and believed in an immaterial origin for the higher mental faculties of humans; he believed that evolution suggested that the universe had a purpose, and that certain aspects of living organisms are not explainable in terms of purely materialistic processes, in a 1909 magazine article entitled "The World of Life", which he later expanded into a book of the same name.[67] Wallace argued in his 1911 book World of Life for a spiritual approach to evolution and described evolution as "creative power, directive mind and ultimate purpose". Wallace believed natural selection could not explain intelligence or morality in the human being so suggested that non-material spiritual forces accounted for these. Wallace believed the spiritual nature of humanity could not have come about by natural selection alone, the origins of the spiritual nature must originate "in the unseen universe of spirit".[68][69]

Oliver Lodge also promoted a version of spiritual evolution in his books Man and the Universe (1908), Making of Man (1924) and Evolution and Creation (1926). The spiritualist element in the synthesis was most prominent in Lodge's 1916 book Raymond, or Life and Death which revived a large interest for the public in the paranormal.[70]

After the 1920s

editAfter the 1920s, spiritualism evolved in three different directions, all of which exist today.

Syncretism

editThe first of these continued the tradition of individual practitioners, organised in circles centered on a medium and clients, without any hierarchy or dogma. Already by the late 19th century spiritualism had become increasingly syncretic, a natural development in a movement without central authority or dogma.[3] Today, among these unorganised circles, spiritualism is similar to the new age movement. However, theosophy, with its inclusion of Eastern religion, astrology, ritual magic and reincarnation, is an example of a closer precursor of the 20th-century new age movement.[71] Today's syncretic spiritualists are quite heterogeneous in their beliefs regarding issues such as reincarnation or the existence of God. Some appropriate new age and neo-pagan beliefs, while others call themselves "Christian spiritualists", continuing with the tradition of cautiously incorporating spiritualist experiences into their Christian faith.

Spiritualist art

editSpiritualism also influenced art, having a pervasive influence on artistic consciousness, with spiritualist art having a huge impact on what became modernism and therefore art today.[72]

Spiritualism also inspired the pioneering abstract art of Vasily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Kasimir Malevich, Hilma af Klint, Georgiana Houghton,[73] and František Kupka.[74]

Spiritualist church

editThe second direction taken has been to adopt formal organization, patterned after Christian denominations, with established liturgies and a set of seven principles, and training requirements for mediums. In the United States the spiritualist churches are primarily affiliated either with the National Spiritualist Association of Churches or the loosely allied group of denominations known as the spiritual church movement; in the U.K. the predominant organization is the Spiritualists' National Union, founded in 1890.[citation needed]

Formal education in spiritualist practice emerged in 1920s, with organizations like the William T. Stead Center in Chicago, Illinois, and continue today with the Arthur Findlay College at Stansted Hall in England, and the Morris Pratt Institute in Wisconsin, United States.[citation needed]

Diversity of belief among organized spiritualists has led to a few schisms, the most notable occurring in the U.K. in 1957 between those who held the movement to be a religion sui generis (of its own with unique characteristics), and a minority who held it to be a denomination within Christianity. In the United States, this distinction can be seen between the less Christian organization, the National Spiritualist Association of Churches, and the more Christian spiritual church movement.[citation needed]

The practice of organized spiritualism today resembles that of any other religion, having discarded most showmanship, particularly those elements resembling the conjurer's art. There is thus a much greater emphasis on "mental" mediumship and an almost complete avoidance of the apparently miraculous "materializing" mediumship that so fascinated early believers such as Arthur Conan Doyle.[75]

Psychical research

editAlready as early as 1882, with the founding of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), parapsychologists emerged to investigate spiritualist claims.[76] The SPR's investigations into spiritualism exposed many fraudulent mediums which contributed to the decline of interest in physical mediumship.[77]

Recognition

editSpiritualism and its belief system were affirmed as covered by the Employment Equality Regulations 2003 at the United Kingdom Employment Appeal Tribunal in 2009.[78]

See also

editReferences

editThis article has an unclear citation style. (January 2024) |

Citations

edit- ^ Melton 2001, p. 1463.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Carroll 1997, p. 248.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Braude 2001, p. 296.

- ^ "Arthur Conan Doyle – The History of Spiritualism Vol I". classic-literature.co.uk. p. 2.

- ^ a b Britten 1884, p. [page needed].

- ^ Campbell, Hardy & Milmokre 1900.

- ^ Lawton 1932, p. 148.

- ^ Bassett 1990, p. 144.

- ^ Urban 2015, p. [page needed].

- ^ Albanese 2007, pp. 171–176, 208–218.

- ^ Davis 1852.

- ^ Weisberg 2004.

- ^ Braude 2001, p. [page needed].

- ^ Strube 2016.

- ^ Deveney 1997.

- ^ a b PBS 1994.

- ^ Troy 2017, p. 151.

- ^ Preliminary Report of the Commission Appointed by the University of Pennsylvania, The Seybert Commission, 1887.

- ^ Williams, Montagu Stephen. 1891. Later Leaves: Being the Further Reminiscences of Montagu Williams. Macmillan. See chapter 8.

- ^ a b Arthur Conan Doyle, The History of Spiritualism Vol I, Arthur Conan Doyle, 1926.

- ^ Spence 2003, p. 679.

- ^ Wallace 1866.

- ^ Anna Hurwic, Pierre Curie, translated by Lilananda Dasa and Joseph Cudnik, Paris, Flammarion, 1995, pp. 65, 66, 68, 247–248.

- ^ "W.T. Stead and Spiritualism – The W.T. Stead Resource Site". attackingthedevil.co.uk.

- ^ Underwood, Peter (1978) "Dictionary of the Supernatural", Harrap Ltd., ISBN 0245527842, p. 144

- ^ "Thomas Edison Had an Idea to Speak with the Dead". 8 March 2015.

- ^ John Fairley, Simon Welfare (1984). Arthur C. Clarke's world of strange powers, Volume 3. Putnam. ISBN 978-0399130663.

- ^ Hereward Carrington. (1907). The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism. Herbert B. Turner & Co.

- ^ McCabe 1920.

- ^ A Magician Among the Spirits, Harry Houdini, Arno Press (June 1987), ISBN 0405028016

- ^ Chung Ling Soo. (1898). Spirit Slate Writing and Kindred Phenomena. Munn & Company.

- ^ Henry Evans. (1897). Hours With the Ghosts Or Nineteenth Century Witchcraft. Kessinger Publishing.

- ^ Julien Proskauer. (1932). Spook crooks! Exposing the secrets of the prophet-eers who conduct our wickedest industry. New York, A. L. Burt.

- ^ Fulton Oursler. (1930). Spirit Mediums Exposed. New York: Macfadden Publications.

- ^ Joseph Dunninger. (1935). Inside the Medium's Cabinet. New York, D. Kemp and Company.

- ^ Rinn 1950.

- ^ "Dead Spiritualist Silent; Detroit Woman Awaits Message, but Denies Any Compact". The New York Times. Detroit. February 8, 1921. p. 3.

- ^ The Light: A Journal Devoted to the Highest Interests of Humanity, both Here and Hereafter, Vol I, January to December 1881, London Spiritualist Alliance, Eclectic Publishing Company: London, 1882.

- ^ "Three Forms of Thought; M.M. Mangassarian Addresses the Society for Ethical Culture at Carnegie Music Hall". The New York Times. 29 November 1897. p. 200.

- ^ Wicker 2004.

- ^ Guthrie, Lucas & Monroe 2000.

- ^ Harrison 1880, p. 6.

- ^ Alvarado, Biondi & Kramer 2006, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Charles Wyllys Elliott, Mysteries, or Glimpses of the Supernatural, Harper & Bros: New York, 1852.

- ^ Catherine Crowe, The Night Side of Nature, or Ghosts and Ghost-seers, Redfield: New York, 1853.

- ^ "Dreadful Tale of a Haunted Man in Newton County, Missouri", Chicago Daily Tribune, January 4, 1891.

- ^ White, Stewart Edward (1943). The Betty Book. US: E. P. Dutton & Co. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0898041514.

- ^ Podmore 2011, pp. 283–287.

- ^ Joseph McCabe. (1920). Spiritualism: A Popular History From 1847. Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 151–173

- ^ Joseph Jastrow. (1918). The Psychology of Conviction. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 101–127

- ^ Mann 1919, pp. 115–130.

- ^ Montague Summers. (2010). Physical Phenomena of Mysticism. Kessinger Publishing. p. 114. ISBN 978-1161363654. Also see Barry Wiley. (2012). The Thought Reader Craze: Victorian Science at the Enchanted Boundary. McFarland. p. 35. ISBN 978-0786464708

- ^ Simeon Edmunds. (1966). Spiritualism: A Critical Survey. Aquarian Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0850300130 "1876 also saw the first of several exposures of another physical medium, William Eglington, in whose trunk a false beard and a quantity of muslin were found by Archdeacon Colley. He was exposed again in 1880, after which he turned to slate-writing. In this he was exposed by Richard Hodgson and S. J. Davey of the SPR in 1885. Davey, a clever conjuror, was able to duplicate all Eglington's phenomena so perfectly that some Spiritualists, notably Alfred Russel Wallace, insisted that he too was really a genuine medium."

- ^ Brian Righi. (2008). Ghosts, Apparitions and Poltergeists: An Exploration of the Supernatural through History. Llewellyn Publications. p. 52. ISBN 978-0738713632 "One medium of the 1920s, Mina Crandon, became famous for producing ectoplasm during her sittings. At the height of the séance, she was even able to produce a tiny ectoplasmic hand from her navel, which waved about in the darkness. Her career ended when Harvard biologists were able to examine the tiny hand and found it to be nothing more than a carved piece of animal liver."

- ^ C. E. M. Hansel. (1989). The Search for Psychic Power: ESP and Parapsychology Revisited. Prometheus Books. p. 245. ISBN 978-0879755331

- ^ McCabe 1920, p. 126.

- ^ Malcolm Gaskill (2001). Hellish Nell: Last of Britain's Witches. Fourth Estate. p. 100. ISBN 978-1841151090

- ^ Jason Karl. (2007). An Illustrated History of the Haunted World. New Holland Publishers. p. 79. ISBN 978-1845376871

- ^ Simeon Edmunds. (1966). Spiritualism: A Critical Survey. Aquarian Press. pp. 137–144. ISBN 978-0850300130

- ^ Kurtz 1985, p. 599.

- ^ Janet Oppenheim, The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914, 1988, p. 267

- ^ a b Janet Oppenheim, The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914, 1988, p. 270

- ^ Butt 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Podmore 2011, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Flower, B. O. (1895). Gerald Massey: Poet, Prophet, and Mystic. Boston: Arena Publishing Company.

- ^ Debora Hammond, The Science of Synthesis: Exploring the Social Implications of General Systems Theory, 2003, p. 39

- ^ Wallace, Alfred Russel. "World of Life". The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Martin Fichman, An elusive Victorian: the evolution of Alfred Russel Wallace, 2004, p. 159

- ^ Clodd 1917, p. 300.

- ^ Peter J. Bowler, Science for all: the popularization of science in early twentieth-century, 2009, p. 44

- ^ Hess 1987, p. 20.

- ^ "The medium's medium: The artists who 'spoke' to the dead".

- ^ World Receivers. Lenbachhaus. 2019. p. 80.

- ^ Brenson, Michael (21 December 1986). "Art View; How the Spiritual Infused the Abstract". The New York Times.

- ^ Guthrie, Lucas & Monroe 2000, p. [page needed].

- ^ Ray Hyman. (1985). A Critical Historical Overview of Parapsychology. In Paul Kurtz. A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology. Prometheus Books. pp. 3–96. ISBN 0879753005

- ^ Rosemary Guiley. (1994). The Guinness Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits. Guinness Publishing. p. 311. ISBN 978-0851127484

- ^ "Greater Manchester Police Authority v Alan Power [2009] UKEAT 0434_09_1211 (12 November 2009)". www.bailii.org.

Works cited

edit- Albanese, Catherine L. (2007). A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion. New Haven/London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300136159.

- Alvarado, Carlos S.; Biondi, Massimo; Kramer, Wim (2006). "Historical Notes on Psychic Phenomena in Specialised Journals". European Journal of Parapsychology. 21 (1): 58–87.

- Bassett, J. (1990). 100 Years of National Spiritualism. The Headquarters Publishing Co.[ISBN missing]

- Braude, Ann (2001). Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253215024. OCLC 47785582.

- Britten, Emma Hardinge (1884). Nineteenth Century Miracles: Spirits and Their Work in Every Country of the Earth. New York: William Britten. ISBN 978-0766162907.

- Butt, G. Baseden (2013) [1925]. Madame Blavatsky. Literary Licensing. ISBN 978-1494069407.

- Campbell, Geo.; Hardy, Thomas; Milmokre, Jas. (June 6, 1900). "Baer-Spiritualistic Challenge". Nanaimo Free Press. Vol. 27, no. 44. Nanaimo, Canada: Geo. Norris. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- Carroll, Bret E. (1997). Spiritualism in Antebellum America. Religion in North America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253333155.

- Clodd, Edward (1917). The Question: A Brief History and Examination of Modern Spiritualism. London: Grant Richards.

- Davis, Andrew Jackson (1852) [1847]. Fishbough, William (ed.). The Principles of Nature, Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind. New York: S. S. Lyon and W. Fishbough – via University of Michigan.

- Deveney, John Patrick (1997). Paschal Beverly Randolph: A Nineteenth-Century Black American Spiritualist, Rosicrucian, and Sex Magician. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791431207.

- Doyle, Arthur Conan (1926). The History of Spiritualism, volume 1. New York: G.H. Doran. ISBN 978-1410102430.

- Doyle, Arthur Conan (1926). The History of Spiritualism, volume 2. New York: G.H. Doran. ISBN 978-1410102430.

- Guthrie, John J. Jr.; Lucas, Phillip Charles; Monroe, Gary, eds. (2000). Cassadaga: the South's Oldest Spiritualist Community. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813017433.

- Harrison, W. H. (1880). Psychic Facts: A Selection from Various Authors. London: Ballantyne Press.

- Hess, David (1987). Spiritism and Science in Brazil (PhD dissertation). Dept. of Anthropology, Cornell University.

- Kurtz, Paul, ed. (1985). A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology. Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879753005.

- Lawton, George (1932). The Drama of Life After Death: A Study of the Spiritualist Religion. Henry Holt and Company. OCLC 936427452.

- Mann, Walter (1919). The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. London: Watts & Co.

- McCabe, Joseph (1920). Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?. London: Watts & Co.

- Melton, J. Gordon, ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology. Vol. 2 (5th ed.). Gale Group. ISBN 0810394898.

- PBS (October 19, 1994). Telegrams from the Dead (television documentary). American Experience.

- Podmore, Frank (2011) [1902, Methuen & Company]. Modern Spiritualism: A History and a Criticism. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108072588.

- Rinn, Joseph (1950). Sixty Years Of Psychical Research: Houdini and I Among the Spiritualists. Truth Seeker.

- Spence, Lewis (2003). Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Kessinger Publishing Company.

- Strube, Julian (2016). "Socialist Religion and the Emergence of Occultism: A Genealogical Approach to Socialism and Secularization in 19th-Century France". Religion. 46 (3): 359–388. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2016.1146926. S2CID 147626697.

- Troy, Kathryn (2017). The Specter of the Indian: Race, Gender, and Ghosts in American Séances, 1848-1890. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1438466095.

- Urban, Hugh B. (2015). New Age, Neopagan and New Religious Movements. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520281189.

- Wallace, Alfred Russel (1866). The Scientific Aspect of the Supernatural. London: F. Farrah – via wku.edu.

- Weisberg, Barbara (2004). Talking to the Dead (1st ed.). San Francisco: Harper. ISBN 978-0060566678. OCLC 54939577.

- Wicker, Christine (2004). Lily Dale: the True Story of the Town that talks to the Dead. San Francisco: Harper.

Further reading

edit- Brandon, Ruth (1983). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Brown, Slater (1970). The Heyday of Spiritualism. New York: Hawthorn Books.

- Buescher, John B. (2003). The Other Side of Salvation: Spiritualism and the Nineteenth-Century Religious Experience. Boston: Skinner House Books. ISBN 978-1558964488.

- Chapin, David (2004). Exploring Other Worlds: Margaret Fox, Elisha Kent Kane, and the Antebellum Culture of Curiosity. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Doyle, Arthur Conan (1975). The History of Spiritualism. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 978-0405070259.

- Lehman, Amy (2009). Victorian Women and the Theatre of Trance: Mediums, Spiritualists and Mesmerists in Performance. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786434794.

- Lindgren, Carl Edwin (January 1994). "Spiritualism: Innocent Beliefs to Scientific Curiosity". Journal of Religion and Psychical Research. 17 (1): 8–15. ISSN 2168-8621. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02.

- Lindgren, Carl Edwin (March 1994). "Scientific investigation and Religious Uncertainty 1880–1900". Journal of Religion and Psychical Research. 17 (2): 83–91. ISSN 2168-8621. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03.

- Moore, William D. (1997). "'To Hold Communion with Nature and the Spirit-World:' New England's Spiritualist Camp Meetings, 1865–1910". In Annmarie Adams; Sally MacMurray (eds.). Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, VII. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0870499838.

- Moreman, Christopher M. (2013). The Spiritualist Movement: Speaking with the Dead in America and around the World 3 Vols. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-39947-3.

- National Spiritualist Association (1934) [1911]. Spiritualist Manual (5 ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Printing Products Corporation.

- Natale, Simone (2016). Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-07104-6.

- Stoddart, Jane (1919). The case against spiritualism. United Kingdom: Hodder & Stoughton.

External links

edit- "American Spirit: A History of the Supernatural" – An hour-long history public radio program exploring American spiritualism.

- Open Directory Project page for "Spiritualism" Archived 2009-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Video and Images of the original Fox Family historic home site. Archived 2012-06-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Investigating Spirit Communications" – Joe Nickell

- "Spiritualism Exposed: Margaret Fox Kane Confesses Fraud" – Skeptic Report