Joseph of Arimathea (Ancient Greek: Ἰωσὴφ ὁ ἀπὸ Ἀριμαθαίας) is a Biblical figure who assumed responsibility for the burial of Jesus after his crucifixion. Three of the four canonical Gospels identify him as a member of the Sanhedrin, while the Gospel of Matthew identifies him as a rich disciple of Jesus. The historical location of Arimathea is uncertain, although it has been identified with several towns. A number of stories about him developed during the Middle Ages.

Joseph of Arimathea | |

|---|---|

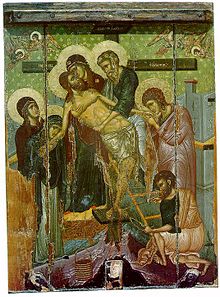

14th century Byzantine Icon of the Descent from the Cross from the Church of Saint Marina in Kalopanagiotis, Cyprus. Saint Joseph of Arimathea is the figure standing in the center, in blue-green robes holding the Body of Christ. | |

| Secret Disciple of Jesus, Righteous | |

| Died | c. 1st century |

| Venerated in | |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Major shrine | Syriac Orthodox Chapel of Holy Sepulchre |

| Feast |

|

| Patronage | Funeral directors and undertakers[2] |

Gospel narratives

editMatthew 27 describes him[a] simply as a rich man and disciple of Jesus, but according to Mark 15, Joseph of Arimathea was "a respected member of the council, who was also himself looking for the kingdom of God".[b] Luke 23 adds that he "had not consented to their decision and action".[c]

According to John 19, upon hearing of Jesus' death, this secret disciple of Jesus "asked Pilate that he might take away the body of Jesus, and Pilate gave him permission."[d] Joseph immediately purchased a linen shroud[e] and proceeded to Golgotha to take the body of Jesus down from the cross. There, Joseph and Nicodemus took the body and bound it in linen cloths with the spices (myrrh and aloes) that Nicodemus had brought.[f] Luke 23:55-56 states that the women "who had come with him from Galilee" prepared the spices and ointments.

The disciples then conveyed the prepared corpse to a man-made cave hewn from rock in a garden nearby. The Gospel of Matthew alone suggests that this was Joseph's own tomb.[g] The burial was undertaken speedily, "for the Sabbath was drawing on".

Veneration

editJoseph of Arimathea is venerated as a saint by the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, and in some Protestant traditions. The traditional Roman calendar marked his feast day on 17 March, but he is now listed, along with Saint Nicodemus, on 31 August in the Martyrologium Romanum. Eastern Orthodox churches commemorate him on the Third Sunday of Pascha (i.e., the second Sunday after Easter) and on 31 July, a date shared by Lutheran churches.[3] He is included in the Myrrhbearers.[4]

Although a series of legends developed during the Middle Ages (perhaps elaborations of early New Testament apocrypha) tied this Joseph to Britain as well as the Holy Grail, he is not currently on the abbreviated liturgical calendar of the Church of England, although he is on the calendars of some churches of the Anglican Communion, such as the Episcopal Church, which commemorates him on 1 August.[5]

Old Testament prophecy

editMany Christians[6] interpret Joseph's role as fulfilling Isaiah's prediction that the grave of the "Suffering Servant" would be with a rich man (Isaiah 53:9), assuming that Isaiah was referring to the Messiah. The prophecy in Isaiah chapter 53 is known as the "Man of Sorrows" passage:

He was assigned a grave with the wicked, and with the rich in his death, though he had done no violence, nor was any deceit in his mouth.

The Greek Septuagint text:

And I will give the wicked for his burial, and the rich for his death; for he practiced no iniquity, nor craft with his mouth.

Development of legends

editSince the 2nd century, a mass of legendary detail has accumulated around the figure of Joseph of Arimathea in addition to the New Testament references. Joseph is referenced in apocryphal and non-canonical accounts such as the Acts of Pilate and the medieval Gospel of Nicodemus. Joseph is mentioned in the works of early church historians such as Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Tertullian, and Eusebius, who added details not found in the canonical accounts. Francis Gigot, writing in the Catholic Encyclopedia, states that "the additional details which are found concerning him in the apocryphal Acta Pilati ("Acts of Pilate"), are unworthy of credence."[7] The Narrative of Joseph of Arimathea, a medieval work, is even purportedly written by him directly, although it adds more details on the robbers at Jesus's crucifixion than Joseph himself.[8] He also appears in the ancient non-canonical text the Gospel of Peter.[9]

Hilary of Poitiers (4th century) enriched the legend, and John Chrysostom, the Patriarch of Constantinople from 397 to 403, was the first to write that Joseph was one of the Seventy Apostles appointed in Luke 10.[10][better source needed]

During the late 12th century, Joseph became connected with Arthurian legend, appearing in them as the first keeper of the Holy Grail. This idea first appears in Robert de Boron's Joseph d'Arimathie, in which Joseph receives the Grail from an apparition of Jesus and sends it with his followers to Britain. This theme is elaborated upon in Boron's sequels and in subsequent Arthurian works penned by others. Later retellings of the story contend that Joseph of Arimathea travelled to Britain and became the first Christian bishop in the Isles, a claim Gigot characterizes as a fable.[7][11]

Gospel of Nicodemus

editThe Gospel of Nicodemus, a text appended to the Acts of Pilate, provides additional details about Joseph. For instance, after Joseph asked Pilate for the body of the Christ and prepared the body with Nicodemus' help, Christ's body was delivered to a new tomb that Joseph had built for himself. In the Gospel of Nicodemus, the Jewish elders express anger at Joseph for burying the body of Christ, saying:

And likewise Joseph also stepped out and said to them: Why are you angry against me because I begged the body of Jesus? Behold, I have put him in my new tomb, wrapping in clean linen; and I have rolled a stone to the door of the tomb. And you have acted not well against the just man, because you have not repented of crucifying him, but also have pierced him with a spear.

— Gospel of Nicodemus. Translated by Alexander Walker.

The Jewish elders then captured Joseph, imprisoned him, and placed a seal on the door to his cell after first posting a guard. Joseph warned the elders, "The Son of God whom you hanged upon the cross, is able to deliver me out of your hands. All your wickedness will return upon you."

Once the elders returned to the cell, the seal was still in place, but Joseph was gone. The elders later discover that Joseph had returned to Arimathea. Having a change in heart, the elders desired to have a more civil conversation with Joseph about his actions and sent a letter of apology to him by means of seven of his friends. Joseph travelled back from Arimathea to Jerusalem to meet with the elders, where they questioned him about his escape. He told them this story:

On the day of the Preparation, about the tenth hour, you shut me in, and I remained there the whole Sabbath in full. And when midnight came, as I was standing and praying, the house where you shut me in was hung up by the four corners, and there was a flashing of light in mine eyes. And I fell to the ground trembling. Then some one lifted me up from the place where I had fallen, and poured over me an abundance of water from the head even to the feet, and put round my nostrils the odour of a wonderful ointment, and rubbed my face with the water itself, as if washing me, and kissed me, and said to me, Joseph, fear not; but open thine eyes, and see who it is that speaks to thee. And looking, I saw Jesus; and being terrified, I thought it was a phantom. And with prayer and the commandments I spoke to him, and he spoke with me. And I said to him: Art thou Rabbi Elias? And he said to me: I am not Elias. And I said: Who art thou, my Lord? And he said to me: I am Jesus, whose body thou didst beg from Pilate, and wrap in clean linen; and thou didst lay a napkin on my face, and didst lay me in thy new tomb, and roll a stone to the door of the tomb. Then I said to him that was speaking to me: Show me, Lord, where I laid thee. And he led me, and showed me the place where I laid him, and the linen which I had put on him, and the napkin which I had wrapped upon his face; and I knew that it was Jesus. And he took hold of me with his hand, and put me in the midst of my house though the gates were shut, and put me in my bed, and said to me: Peace to thee! And he kissed me, and said to me: For forty days go not out of thy house; for, lo, I go to my brethren into Galilee.

— Gospel of Nicodemus. Translated by Alexander Walker

According to the Gospel of Nicodemus, Joseph testified to the Jewish elders, and specifically to chief priests Caiaphas and Annas that Jesus had risen from the dead and ascended to heaven, and he indicated that others were raised from the dead at the resurrection of Christ (repeating Matt 27:52–53). He specifically identified the two sons of the high-priest Simeon (again in Luke 2:25–35). The elders Annas, Caiaphas, Nicodemus, and Joseph himself, along with Gamaliel under whom Paul of Tarsus studied, travelled to Arimathea to interview Simeon's sons Charinus and Lenthius.

Other medieval texts

editMedieval interest in Joseph centered on two themes, that of Joseph as the founder of British Christianity (even before it had taken hold in Rome), and that of Joseph as the original guardian of the Holy Grail.

Britain

editMany legends about the arrival of Christianity in Britain abounded during the Middle Ages. Early writers do not connect Joseph to this activity, however. Tertullian wrote in Adversus Judaeos that Britain had already received and accepted the Gospel in his lifetime, writing, "all the limits of the Spains, and the diverse nations of the Gauls, and the haunts of the Britons—inaccessible to the Romans, but subjugated to Christ."[12]

Tertullian does not say how the Gospel came to Britain before AD 222. However, Eusebius of Caesaria, one of the earliest and most comprehensive of church historians, wrote of Christ's disciples in Demonstratio Evangelica, saying that "some have crossed the Ocean and reached the Isles of Britain."[13] Hilary of Poitiers also wrote that the Apostles had built churches and that the Gospel had passed into Britain.[14] The writings of Pseudo-Hippolytus include a list of the seventy disciples whom Jesus sent forth in Luke 10, one of which is Aristobulus of Romans 16:10, called "bishop of Britain".[15]

In none of these earliest references to Christianity's arrival in Britain is Joseph of Arimathea mentioned. William of Malmesbury's De Antiquitate Glastoniensis Ecclesiae ('On the Antiquity of the Church of Glastonbury', circa 1125) has not survived in its original edition, and the stories involving Joseph of Arimathea are contained in subsequent editions that abound in interpolations placed by the Glastonbury monks "in order to increase the Abbey's prestige – and thus its pilgrim trade and prosperity" [16] In his Gesta Regum Anglorum (History of The Kings of England, finished in 1125), William of Malmesbury wrote that Glastonbury Abbey was built by preachers sent by Pope Eleuterus to Britain, however also adding: "Moreover there are documents of no small credit, which have been discovered in certain places to the following effect: 'No other hands than those of the disciples of Christ erected the church of Glastonbury'", but here William did not explicitly link Glastonbury with Joseph of Arimathea, but instead emphasizes the possible role of Philip the Apostle: "if Philip, the Apostle, preached to the Gauls, as Freculphus relates in the fourth chapter of his second book, it may be believed that he also planted the word on this side of the channel also.".[17] The first appearance of Joseph in the Glastonbury records can be pinpointed with surprising accuracy to 1247, when the story of his voyage was added as a margin-note to Malmesbury's chronicle.[18]

In 1989, folklore scholar A. W. Smith critically examined the accretion of legends around Joseph of Arimathea. Often associated with William Blake's poem "And did those feet in ancient time" and its musical setting, widely known as the hymn "Jerusalem", the legend is commonly held as "an almost secret yet passionately held article of faith among certain otherwise quite orthodox Christians" and Smith concluded "that there was little reason to believe that an oral tradition concerning a visit made by Jesus to Britain existed before the early part of the twentieth century".[19] Sabine Baring-Gould recounted a Cornish story how "Joseph of Arimathea came in a boat to Cornwall, and brought the child Jesus with him, and the latter taught him how to extract the tin and purge it of its wolfram. This story possibly grew out of the fact that the Jews under the Angevin kings farmed the tin of Cornwall."[20] In its most developed version, Joseph, a tin merchant, visited Cornwall, accompanied by his nephew, the boy Jesus. Reverend C.C. Dobson (1879–1960) made a case for the authenticity of the Glastonbury legenda.[21] The case was argued more recently by the Church of Scotland minister Gordon Strachan (1934–2010) [22] and by the former archaeologist Dennis Price.[23]

Holy Grail

editThe legend that Joseph was given the responsibility of keeping the Holy Grail was the product of Robert de Boron, who essentially expanded upon stories from Acts of Pilate. In Boron's Joseph d'Arimathie, Joseph is imprisoned much as in the Acts of Pilate, but it is the Grail that sustains him during his captivity. Upon his release he founds his company of followers, who take the Grail to the "Vale of Avaron" (identified with Avalon), though Joseph does not go. The origin of the association between Joseph and Britain, where Avalon is presumed to be located, is not entirely clear, though in subsequent romances such as Perlesvaus, Joseph travels to Britain, bringing relics with him. In the Lancelot-Grail cycle, a vast Arthurian composition that took much from Robert, it is not Joseph but his son Josephus who is considered the primary holy man of Britain.

Later authors sometimes mistakenly or deliberately treated the Grail story as truth. Such stories were inspired by the account of John of Glastonbury, who assembled a chronicle of the history of Glastonbury Abbey around 1350 and who wrote that Joseph, when he came to Britain, brought with him vessels containing the blood and sweat of Christ (without using the word Grail).[24] This account inspired the future claims of the Grail, including the claim involving the Nanteos Cup on display in the museum in Aberystwyth. There is no reference to this tradition in ancient or medieval text. John of Glastonbury further claims that King Arthur was descended from Joseph, listing the following imaginative pedigree through King Arthur's mother:

Helaius, Nepos Joseph, Genuit Josus, Josue Genuit Aminadab, Aminadab Genuit Filium, qui Genuit Ygernam, de qua Rex Pen-Dragon, Genuit Nobilem et Famosum Regum Arthurum, per Quod Patet, Quod Rex Arthurus de Stirpe Joseph descendit.

Joseph's alleged early arrival in Britain was used for political point-scoring by English theologians and diplomats during the late Middle Ages, and Richard Beere, Abbot of Glastonbury from 1493 to 1524, put the cult of Joseph at the heart of the abbey's legendary traditions. He was probably responsible for the drastic remodelling of the Lady Chapel at Glastonbury Abbey. A series of miraculous cures took place in 1502 which were attributed to the saint, and in 1520 the printer Richard Pynson published a Lyfe of Joseph of Armathia, in which the Glastonbury Thorn is mentioned for the first time.[25] Joseph's importance increased exponentially with the English Reformation, since his alleged early arrival far predated the Catholic conversion of AD 597. In the new post-Catholic world, Joseph stood for Christianity pure and Protestant. In 1546, John Bale, a prominent Protestant writer, claimed that the early date of Joseph's mission meant that original British Christianity was purer than that of Rome, an idea which was understandably popular with English Protestants, notably Queen Elizabeth I herself, who cited Joseph's missionary work in England when she told Roman Catholic bishops that the Church of England pre-dated the Roman Church in England.[26][27]

Other legends

editAccording to one of England's best-known legends, when Joseph and his followers arrived, weary, on Wearyall Hill outside Glastonbury, he set his walking staff on the ground and it miraculously took root and blossomed as the "Glastonbury Thorn". The mytheme of the staff that Joseph of Arimathea set in the ground at Glastonbury, which broke into leaf and flower as the Glastonbury Thorn is a common miracle in hagiography. Such a miracle is told of the Anglo-Saxon saint Etheldreda:

Continuing her flight to Ely, Etheldreda halted for some days at Alfham, near Wintringham, where she founded a church; and near this place occurred the "miracle of her staff". Wearied with her journey, she one day slept by the wayside, having fixed her staff in the ground at her head. On waking she found the dry staff had burst into leaf; it became an ash tree, the "greatest tree in all that country;" and the place of her rest, where a church was afterwards built, became known as "Etheldredestow".

— Richard John King, 1862, in: Handbook of the Cathedrals of England; Eastern division: Oxford, Peterborough, Norwich, Ely, Lincoln.[28]

Medieval interest in genealogy raised claims that Joseph was a relative of Jesus; specifically, Mary's uncle, or according to some genealogies, Joseph's uncle. A genealogy for the family of Joseph of Arimathea and the history of his further adventures in the east provide material for the Estoire del Saint Graal and the Queste del Saint Graal of the Lancelot-Grail cycle and Perlesvaus.[29]

Another legend, as recorded in Flores Historiarum, is that Joseph is in fact the Wandering Jew, a man cursed by Jesus to walk the Earth until the Second Coming.[30]

Arimathea

editArimathea is not otherwise documented, though it was "a town of Judea" according to Luke 23:51. Arimathea is usually identified with either Ramleh or Ramathaim-Zophim, where David came to Samuel in the first Book of Samuel, chapter 19.[h][31]

See also

editNotes

editBiblical verses cited

editReferences

edit- ^ Domar: the calendrical and liturgical cycle of the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church 2003, Armenian Orthodox Theological Research Institute, 2002, p. 531.

- ^ Thomas Craughwell (2005). "A Patron Saint for Funeral Directors". Catholicherald.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ Kinnaman, Scott A. (2010). Lutheranism 101. St. Louis, Missouri: Concordia Publishing House. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-7586-2505-2.

- ^ "Learn about the Orthodox Christian Faith - Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America".

- ^ Church, The Episcopal (24 January 2023). Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2022. Church Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-64065-627-7.

- ^ E.g. Ben Witherington III, John's Wisdom: A Commentary on the Fourth Gospel, 1995, and Andreas J. Köstenberger in Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament, 2007, on John 19:38–42.

- ^ a b "Joseph of Arimathea". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1910. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart; Pleše, Zlatko (2011). The Apocryphal Gospels: Texts and Translations. Oxford University Press. p. 305–312. ISBN 978-0-19-973210-4.

- ^ Walter Richard (1894). The Gospel According to Peter: A Study. Longmans, Green. p. 8. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ John Chrysostom, Homilies of St. John Chrysostom on the Gospel of John.

- ^ Finally, the story of the translation of the body of Joseph of Arimathea from Jerusalem to Moyenmonstre (Diocese of Toul) originated late and is unreliable."

- ^ "Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. III : An Answer to the Jews". www.tertullian.org.

- ^ "Eusebius of Caesarea: Demonstratio Evangelica. Tr. W.J. Ferrar (1920) -- Book 3". www.tertullian.org.

- ^ "NPNF2-09. Hilary of Poitiers, John of Damascus - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: On the Apostles and Disciples (Pseudo-Hippolytus)". newadvent.org.

- ^ Antonia Gransden, Historical Writing in England II, c. 1307 to the Present, page 399. Routledge, 1996; Reprinted 2000. ISBN 0-415-15125-2. Antonia Grandsen also cited William Wells Newell, "William of Malmesbury on the Antiquity of Glastonbury" in Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, xviii (1903), pages 459–512; A. Gransden, "The Growth of the Glastonbury Traditions and Legends in the Twelfth Century" in Journal of Ecclesiastical History, xxvii (1976), page 342

- ^ William of Malmesbury, William of Malmesbury's Chronicle of the Kings of England: From the Earliest Period To The Reign of King Stephen, page 22 (notes and illustrations by J. A. Giles, London: Bell & Daldy, 1866)

- ^ Stout, Adam (2020) Glastonbury Holy Thorn: Story of a Legend Green & Pleasant Publishing, p. 14 ISBN 978-1-9162686-1-6

- ^ Smith, "'And Did Those Feet...?': The 'Legend' of Christ's Visit to Britain" Folklore 100.1 (1989), pp. 63–83.

- ^ S. Baring-Gould, A Book of The West: Being An Introduction To Devon and Cornwall (2 Volumes, Methuen Publishing, 1899); A Book of Cornwall, Second Edition 1902, New Edition, 1906, page 57.

- ^ Dobson, Did Our Lord Visit Britain as they say in Cornwall and Somerset? (Glastonbury: Avalon Press) 1936.

- ^ Strachan, Gordon (1998). Jesus, the Master Builder: Druid Mysteries and the Dawn of Christianity. Edinburgh: Floris Books. ISBN 9780863152757.

- ^ Dennis Price, The Missing Years of Jesus: The Greatest Story Never Told (Hay House Publishing, 2009). ISBN 9781848500334

- ^ Edward Donald Kennedy, "Visions of History: Robert de Boron and English Arthurian Chronicles" in, Norris J. Lacy, editor, The Fortunes of King Arthur, page 39 (D. S. Brewer, Cambridge, 2005). ISBN 1-84384-061-8

- ^ Stout, Adam (2020) Glastonbury Holy Thorn: Story of a Legend Green & Pleasant Publishing, pp. 13-16 ISBN 978-1-9162686-1-6

- ^ "Elizabeth's 1559 reply to the Catholic bishops". fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2006.

- ^ Stout, Adam (2020) Glastonbury Holy Thorn: Story of a Legend Green & Pleasant Publishing, pp. 23-24 ISBN 978-1-9162686-1-6

- ^ "History of the See of Ely • King's Handbook to the Cathedrals of England". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ C. Scott Littleton, Linda A. Malcor, From Scythia to Camelot: a radical reassessment of the legends of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table and the Holy Grail (1994) 2000:310.

- ^ Percy, Thomas (2001) [1847]. Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Vol. 2. Adamant Media Corporation. p. 246. ISBN 1-4021-7380-6.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, article "al-Ramla".

External links

edit- The History of that Holy Disciple Joseph of Arimathea by Anonymous (1770)

- Qumran text of Isaiah 53