This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

A government bond or sovereign bond is a form of bond issued by a government to support public spending. It generally includes a commitment to pay periodic interest, called coupon payments, and to repay the face value on the maturity date.

For example, a bondholder invests $20,000, called face value or principal, into a 10-year government bond with a 10% annual coupon; the government would pay the bondholder 10% interest ($2000 in this case) each year and repay the $20,000 original face value at the date of maturity (i.e. after 10 years).

Government bonds can be denominated in a foreign currency or the government's domestic currency. Countries with less stable economies tend to denominate their bonds in the currency of a country with a more stable economy (i.e. a hard currency). All bonds carry default risk; that is, the possibility that the government will be unable to pay bondholders. Bonds from countries with less stable economies are usually considered to be higher risk. International credit rating agencies provide ratings for each country's bonds. Bondholders generally demand higher yields from riskier bonds. For instance, on May 24, 2016, 10-year government bonds issued by the Canadian government offered a yield of 1.34%, while 10-year government bonds issued by the Brazilian government offered a yield of 12.84%.

Governments close to a default are sometimes referred to as being in a sovereign debt crisis.[1][2]

History

editThe Dutch Republic became the first state to finance its debt through bonds when it assumed bonds issued by the city of Amsterdam in 1517. The average interest rate at that time fluctuated around 20%.

The first official government bond issued by a national government was issued by the Bank of England in 1694 to raise money to fund a war against France. The form of these bonds was both lottery and annuity. The Bank of England and government bonds were introduced in England by William III of England (also called William of Orange), who financed England's war efforts by copying the approach of issuing bonds and raising government debt from the Seven Dutch Provinces, where he ruled as a stadtholder.

Later, governments in Europe started following the trend and issuing perpetual bonds (bonds with no maturity date) to fund wars and other government spending. The use of perpetual bonds ceased in the 20th century, and currently governments issue bonds of limited term to maturity.

During the American Revolution, in order to raise money, the U.S. government started to issue bonds - called loan certificates. The total amount generated by bonds was $27 million and helped finance the war.[3]

Risks

editCredit risk

editA government bond in a country's own currency is strictly speaking a risk-free bond, because the government can if necessary create additional currency in order to redeem the bond at maturity. For most governments, this is possible only through the issue of new bonds, as the governments have no possibility to create currency. (The issue of bonds which are then bought by the central bank with newly created currency in the process of "quantitative easing" may be regarded as de facto direct state financing from the central bank, which is outlawed officially for independent central banks.) There have been instances where a government has chosen to default on its domestic currency debt rather than create additional currency, such as Russia in 1998 (the "ruble crisis") (see national bankruptcy).

Investors may use rating agencies to assess credit risk. In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has designated ten rating agencies as nationally recognized statistical rating organizations.

Currency risk

editCurrency risk is the risk that the value of the currency a bond pays out will decline compared to the holder's reference currency. For example, a German investor would consider United States bonds to have more currency risk than German bonds (since the dollar may go down relative to the euro); similarly, a United States investor would consider German bonds to have more currency risk than United States bonds (since the euro may go down relative to the dollar). A bond paying in a currency that does not have a history of keeping its value may not be a good deal even if a high interest rate is offered.[4] The currency risk is determined by the fluctuation of exchange rates.

Inflation risk

editInflation risk is the risk that the value of the currency a bond pays out will decline over time. Investors expect some amount of inflation, so the risk is that the inflation rate will be higher than expected. Many governments issue inflation-indexed bonds, which protect investors against inflation risk by linking both interest payments and maturity payments to a consumer price index. In the UK these bonds are called Index-linked bonds. In the US these bonds are called Series I bonds.

Interest rate risk

editAlso referred to as market risk, all bonds are subject to interest rate risk. Interest rate changes can affect the value of a bond. If the interest rates fall, then the bond prices rise and if the interest rates rise, bond prices fall. When interest rates rise, bonds are more attractive because investors can earn higher coupon rate, thereby holding period risk may occur. Interest rate and bond price have negative correlation. Lower fixed-rate bond coupon rates meaning higher interest rate risk and higher fixed-rate bond coupon rates meaning lower interest rate risk. Maturity of a bond also has an impact on the interest rate risk. Indeed, longer maturity meaning higher interest rate risk and shorter maturity meaning lower interest rate risk.

Money supply

editIf a central bank purchases a government security, such as a bond or treasury bill, it increases the money supply because a Central Bank injects liquidity (cash) into the economy. Doing this lowers the government bond's yield. On the contrary, when a Central Bank is fighting against inflation then a Central Bank decreases the money supply.

These actions of increasing or decreasing the amount of money in the banking system are called monetary policy.

United Kingdom

editIn the UK, government bonds are called gilts. Older issues have names such as "Treasury Stock" and newer issues are called "Treasury Gilt".[5][6] Inflation-indexed gilts are called Index-linked gilts.,[7] which means the value of the gilt rises with inflation. They are fixed-interest securities issued by the British government in order to raise money.[citation needed] The issuance of gilts is managed by the UK Debt Management Office, an executive agency of HM Treasury. Prior to April 1998, gilts were issued by the Bank of England.[8] Purchase and sales services are managed by Computershare.[9]

UK gilts have maturities stretching much further into the future than other European government bonds, which has influenced the development of pension and life insurance markets in the respective countries.

A conventional UK gilt might look like this – "Treasury stock 3% 2020".[10] On the 27 of April 2019 the United Kingdom 10Y Government Bond had a 1.145% yield. Central Bank Rate is 0.10% and the United Kingdom rating is AA, according to Standard & Poor's.[11]

United States

editThe U.S. Treasury offered several types of bonds with various maturities. Certain bonds may pay interest, others not. These bonds could be:

- Savings bonds: they are considered one of the safest investments.

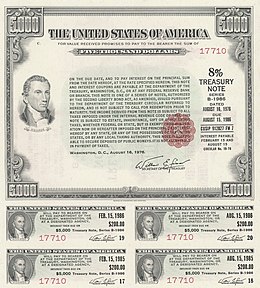

- Treasury notes (T-notes): maturity of these bonds is two, three, five or 10 years, they provided fixed coupon payments every six months and have face value of $1,000.

- Treasury bonds (T-bonds or long bonds): are the treasury bonds with the longest maturity, from twenty years to thirty years. They also have a coupon payment every six months.

- Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS): are the inflation-indexed bond issued by the U.S. Treasury. The principal of these bonds is adjusted to the Consumer Price Index. In other words, the principal increases with inflation and decreases with deflation.

The principal argument for investors to hold U.S. government bonds is that the bonds are exempt from state and local taxes.

The bonds are sold through an auction system by the government. The bonds are buying and selling on the secondary market, the financial market in which financial instruments such as stock, bond, option and futures are traded.

TreasuryDirect is the official website where investors can purchase treasury securities directly from the U.S. government. This online system allow investors to save money on commissions and fees taken with traditional channels. Investors can use banks or brokers to hold a bond.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "What is Sovereign Debt". Archived from the original on 2020-07-02. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ^ "Portugal sovereign debt crisis". Archived from the original on 2014-08-10. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ^ "investopedia.com". investopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Analysis: Counting the cost of currency risk in emerging bond markets". Reuters. 22 November 2013. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Daily Prices and Yields". UK Debt Management Office. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Gilt Market: About gilts". UK Debt Management Office. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ "Gilt Market: Index-linked gilts". UK Debt Management Office. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ "Gilt Market". UK Debt Management Office. 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Computershare to take over from Bank of England as UK gilts registrar". Thomson Reuters Practical Law. 16 July 2004. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Kaveh, Kim (2016-08-02). "Gilts and corporate bonds explained". Which? Money. Archived from the original on 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ "United Kingdom Government Bonds - Yields Curve". World Government Bonds. Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2022-02-07.