The black-necked swan (Cygnus melancoryphus) is a species of waterfowl in the tribe Cygnini of the subfamily Anserinae.[5][6] It is found in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and the Falkland Islands.[7]

| Black-necked swan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Black-necked swan at the San Francisco Zoo, USA | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Cygnus |

| Species: | C. melancoryphus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cygnus melancoryphus | |

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

Taxonomy and systematics

editThe black-necked swan has occasionally been placed by itself in the genus Sthenelides. Its closest relatives are the black swan (C. atratus) and mute swan (C. olor).[4] It is monotypic.[5]

Description

editThe black-necked swan is the only member of its genus that breeds in the neotropics and is the largest waterfowl native to South America. Adults are 102 to 124 cm (40 to 49 in) long with a wingspan of 135 to 177 cm (53 to 70 in). Males weigh 4.6 to 8.7 kg (10 to 19 lb) and females 3.5 to 4.4 kg (7.7 to 9.7 lb). The sexes are alike. Adults' body plumage is white and the neck and head black; the latter usually has a white stripe behind the eye. They have a prominent red knob at the base of their bill. Juveniles are grayish rather than white and lack the knob until their third or fourth year.[4][8]

Distribution and habitat

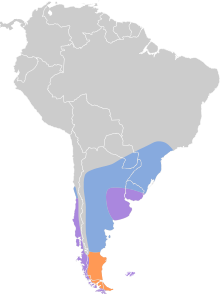

editThe black-necked swan is found in the southern tier of South America. It nests from Tierra del Fuego north to central Chile, Uruguay, and Rio Grande do Sul in extreme southern Brazil. It withdraws from the southern half of Argentina in winter and is then found as far north as Brazil's São Paulo state. It is a year-round resident of the Falkland Islands. Vagrants have been found on Juan Fernández Island, the South Orkney Islands, the South Shetland Islands, and the Antarctic Peninsula.[4]

The black-necked swan inhabits freshwater marshes and swamps, shallow lakes, brackish lagoons, and sheltered coastal sites. On the mainland of South America, it is often found near human habitation but shuns built-up areas in the Falklands. It is generally found at low elevations but non-breeding flocks can be found as high as 900 to 1,250 metres (3,000 to 4,100 ft) in the Andes of southern Argentina.[4]

The wetlands created in Chile by the 1960 Valdivia earthquake, such as Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary on the Cruces River, have become important population centers for the black-necked swan.[9] The population in this sanctuary has fluctuated widely over the years, reaching a low of 214 in January 2008 and a peak of 22,419 in May 2020 before plumbing to 2,782 in May 2022.[10][11]

Behavior

editFeeding

editThe black-necked swan's diet is almost entirely vegetarian. It feeds on aquatic plants like Chara, Potamogeton, Typha; algae such as Aphantotece and Rhyzoclonium; and presumably small numbers of aquatic invertebrates. In parts of Chile its principal food is Egeria densa. It forages mostly by immersing its head and neck and by surface feeding, but also upends to reach deeper. In times of drought it has been observed grazing in meadows and pastures.[4]

Breeding

editThe black-necked swan's breeding season varies geographically. In the far south of its range, it breeds from July to November but ends as early as September in the northern parts. In the Falklands, it breeds between August and November. The exact timing of breeding appears dependent on rainfall. The species is believed to form long-term pair bonds. Its nest is a mound of vegetation constructed by both members of a pair on a small islet or partially floating in a reedbed. The clutch size is four to eight eggs. Males guard females during the 34- to 36-day incubation period. Captive nestlings fledged about 100 days after hatch.[4]

Vocalization

editThe black-necked swan is mostly silent outside the breeding season. During that time, both sexes give a "soft, musical 'Whee-whee-whee' with the accent on the initial syllable", repeating it to challenge intruders. The call is also used to maintain contact between members of a pair. Males also give "a musical 'hooee-hoo-hoo'."[4]

Diseases

editBlack-necked swans can contract avian influenza. In March 2023 influenza A virus subtype H5N1 was detected in black-necked swan populations in Carlos Anwandter Nature Sanctuary, Chile and Estación Tapia, Uruguay.[12][13] As on May 30, 2023, three more black-necked swans were found dead due to influenza H5N1 in Lagoa da Mangueira, Taim Ecological Station, Brasil.[14] This raises the total at that station to 63.[14]

Status and conservation

editThe IUCN has assessed the black-necked swan as being of Least Concern. It has a very large range, and though its population size is not known, it is believed to be stable. No immediate threats have been identified.[1] It is widespread and generally common. Large-scale hunting in the 18th and 19th centuries extirpated it from much of Chile but it has recolonized those areas. Some egg collecting and hunting still occur, however. The species occurs in several protected areas in mainland Argentina, in which country the population is estimated at 50,000.[4]

Gallery

editReferences

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22679846A92832118. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22679846A92832118.en. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ "Cygnus melanocoryphus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carboneras, C. and G. M. Kirwan (2020). Black-necked Swan (Cygnus melancoryphus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blnswa2.01 retrieved September 27, 2022

- ^ a b Gill, F.; Donsker, D.; Rasmussen, P., eds. (August 2022). "Screamers, ducks, geese, swans". IOC World Bird List. v 12.2. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ HBW and BirdLife International (2021) Handbook of the Birds of the World and BirdLife International digital checklist of the birds of the world. Version 6. Available at: http://datazone.birdlife.org/userfiles/file/Species/Taxonomy/HBW-BirdLife_Checklist_v6_Dec21.zip retrieved August 7, 2022

- ^ Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, J. F. Pacheco, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 24 July 2022. Species Lists of Birds for South American Countries and Territories. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCCountryLists.htm retrieved July 24, 2022

- ^ Ogilvie & Young, Wildfowl of the World. New Holland Publishers (2004), ISBN 978-1-84330-328-2

- ^ Ramirez, C., E. Carrasco, S. Mariani & N. Palacios. 2006. La desaparición del luchecillo (Egeria densa) del Santuario del Rio Cruces (Valdivia, Chile): una hipótesis plausible. Ciencia & Trabajo, 20: 79-86

- ^ Cassinelli, Francisca. "¿Qué pasó con los cisnes de cuello negro en Valdivia después del desastre ecológico de 2004?". 24horas (in Spanish). Televisión Nacional de Chile. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ Lara, Emilio; López, Carlos (2022-06-03). "Se desploma cantidad de cisnes de cuello negro en santuario de Valdivia: no hay nidos ni huevos". Radio Bío-Bío (in Spanish).

- ^ Salgado, Daniela; López, Carlos (2023-03-25). "Influenza aviar: declaran emergencia zoosanitaria por contagio de cisnes de cuello negro en Valdivia". Radio Bío-Bío (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ "En Uruguay siguen apareciendo casos de gripe aviar". Diario El Comercial (in Spanish). 2023-03-15. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ^ a b Teixeira, Thaise (2023). "Taim registra mais três mortes de cisnes-de-pescoço-preto". Correio do Povo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-06-05.

Further reading

edit- David, N. & Gosselin, M. (2002). "Gender agreement of avian species names." Bull. B. O. C. 122: 14–49.

External links

edit- Stamps[usurped] (for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Falkland Islands, Uruguay) with RangeMap

- Black-necked Swan photo gallery VIREO