Santa Fe Indian School (SFIS) is a tribal boarding secondary school in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It is affiliated with the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE).

| Santa Fe Indian School | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Address | |

| |

1501 Cerrillos Road P.O. Box 5340 , 87501 | |

| Information | |

| School type | Boarding School |

| Established | 1890 |

| School board | Northern Pueblos Education Line Office |

| Superintendent | Christie Abeyta |

| Grades | 7–12 |

| Enrollment | 709 (2005–2006)[1] |

| Color(s) | Maroon & Gold |

| Athletics conference | NMAA AAA District 2 |

| Team name | Braves |

| Website | http://www.sfis.k12.nm.us/ |

History

editThe Federal Government established the Santa Fe Indian School to educate Native American children from tribes throughout the Southwestern United States. Although the school gives its founding date as 1890,[2] The Santa Fe New Mexican reported an enrollment of 40 students in April 1885 and 200 students in April 1887.[3] The school enrolled students from Laguna Pueblo, Santo Domingo Pueblo, San Felipe Pueblo, and Zuni Pueblo. The purpose of creating SFIS was an attempt to assimilate the Native American children into the wider United States culture and economy.[4] In 1975, the All Indian Pueblo Council (AIPC) was formed. It was the first Indian organization to utilize the laws in place to contract an education for their children. Eventually, the AIPC was able to leverage complete control of the school and curriculum. In 2001, with the passing of the SFIS Act, the school took ownership of the land.[4] The school resides on the form of a trust, which is held by the nineteen Pueblo Governors of New Mexico. These acts allow for complete educational sovereignty of the school, by the Pueblo.[5]

Indian Boarding Schools origins

editThe original concept of the Indian Boarding School began as a social experiment predating the Civil War. Around the 1860s, the United States Federal Government created "day schools" to educate children about Western civilisation. They were ineffective in this process because the students did not retain the knowledge acquired at school. A factor in knowledge retention was the students returning home. After discovering this method of education was ineffective, a different approach was taken.[6]

In the 1870s, the concept of Indian Boarding Schools came into fruition. Army Lt. Richard Henry Pratt was charged with overseeing seventy-two Native American prisoners who fought against the Army; he tested his version of the social experiment that was previously attempted on the children. Pratt desired to mold the "savages" into "civilized" people.[7] Pratt taught the Native American prisoners how to speak English and educated the Native Americans on European society and religion. After this educational experience, sixty-two of the Natives went to the Hampton Institute in Virginia. Deciding to extend the experiment further, Pratt was able to convince Native American families to allow their children to attend his boarding school.

Richard H. Pratt founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879;[6] the difference being, unlike day schools, Carlisle was located over a thousand miles away from the reservation. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the first boarding school specifically for Native Americans. The reasoning behind positioning the school a great distance from the reservations was that Pratt believed distance would help break the ties to Native American culture. He has been quoted as saying, "In Indian civilization I am a Baptist, because I believe in immersing the Indian in our civilization and when we get them under, holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.".[6]

Pratt desired to remove the children from their Native roots, and he was harsh in the actions he took. Being that Pratt was from the Armed Forces, his background dictated how he operated the school. The students were forced to cut their hair, a symbol of their pride. One boarding school student was quoted as saying, "[Long hair] was the pride of all Indians. The boys, one by one, would break down and cry when they saw their braids thrown on the floor. All of the buckskin clothes had to go and we had to put on the clothes of the White Man".[8] The students were stripped of all traces of what their culture was, such as: their long hair, their clothing, and their native language. The same student went on to say, "This is when the loneliness set in, for it was when we knew that we were all alone. Many boys ran away from the school because the treatment was so bad, but most of them were caught and brought back by the police".[9] Having to deal with the oppression of the school and lack of contact from their families, the students were struck with a feeling of loneliness.

Reformation of Indian Boarding Schools

editChanges to the system of the Indian Boarding School took place over the 20th and 21st century.[10] The school system reformed to its current iteration. In the 1920s, Hubert Work, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, authorized an investigation on the conditions of Indian Boarding Schools; the group reported their findings in the Meriam Report that highlighted the failures of the boarding school system.[11] In the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, a shift in Federal Native American policy began when President Roosevelt established the Indian New Deal with the purpose of protecting the Native population residing within the United States. The cornerstone of the Indian New Deal was the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934. This act allowed for the Native Americans to construct their own constitutions and govern themselves.[12] In the same year, the Johnson–O'Malley Act was passed to fund Native American education.[13]

In 1966, the Rough Rock Demonstration School was opened. The school was on Navajo land, and was the first boarding school controlled by the Indians.[14] Seeing the success of the Rough Rock Demonstration School, a report was filed in 1969 entitled "Indian Education: A National Tragedy, A National Challenge", which stated that the U.S government's assimilation policy "has had disastrous effects on the education of Indian children".[15] Following this report, the Indian Education Act of 1972 established the Office of Indian Education.[16] The Indian Self Determination and Educational Assistance Act, established in 1975, gave the American Indians the opportunity to legislate "self-determination through community-based schooling".[17] In 1990, the Native American Languages Act granted language rights to Native Americans. The Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act was established in 2006, which created programs for Native American Language immersion. These changes brought reform the Indian Boarding Schools needed.[10]

The Federal Government established the Santa Fe Indian School (SFIS) in 1890 to educate Native American children from tribes throughout the Southwestern United States. The purpose of creating SFIS was an attempt to assimilate the Native American children into the wider United States culture and economy.[4] In 1975, the All Indian Pueblo Council (AIPC) was formed. It was the first Indian organization to utilize the laws in place to contract an education for their children. Eventually, the AIPC was able to leverage complete control of the school and curriculum. In 2001, with the passing of the SFIS Act, the school took ownership of the land.[4] The school resides on the form of a trust, which is held by the nineteen Pueblo Governors of New Mexico. These acts allow for complete educational sovereignty of the school, by the Pueblo.[5]

The Studio School

editIn 1932, Dorothy Dunn established "The Studio School" at the Santa Fe Indian School. It was a painting program for Native Americans, which encouraged students to develop a painting style that was derived from their cultural traditions. Dunn left in 1937, and was replaced by Gerónima Cruz Montoya of Ohkay Owingeh, who taught until the program closed in 1962, with the opening of the Institute of American Indian Arts.[18] Tonita Peña had been an instructor at the school in the 1930s.[19]

Notable alumni of The Studio School

editNotable alumni include:

Demolition and restoration

editSince officially taking control of SFIS, the nineteen Pueblo Tribes began to take action in demolishing and renovating SFIS in the early 2000s. In 2008, the SFIS razed eighteen buildings. Some preservationists were upset by the demolition. School officials stated: "After completing various assessments over the past five years, the Santa Fe Indian School exercised its sovereign authority and due diligence to take action by demolishing buildings to remove the imminent health, safety, and security threats to protect the students and staff of SFIS, including the general public".[20] There was questioning of whether or not SFIS had the right to raze the buildings. After reviewing the different laws and regulations, the sovereignty overruled the Historic Preservation Acts; the Pueblo were able to demolish the historic buildings without retribution.[20] The Pueblo stated the buildings being torn down contained asbestos. They did not have the funds to repair the buildings and maintain them.

The demolition of these historic buildings, in turn, had many benefits for the Tribes. "A Pueblo governor reportedly called the demolition of the buildings "a spiritual cleansing" for his people".[20] "Spiritual cleansing" was desired by the Pueblo Tribes after years of attending Indian Boarding Schools and assimilating to different ideals.[20] The restoration of the school contributed to enhancing and reviving the overall cultural experience of the school. The rebuilding of the school was a collaborative design build project between Albuquerque offices of Flintco Construction and ASCG. To create a welcoming, home-like environment, SFIS included fireplaces in the dorms and classrooms. SFIS believes creating a familiar environment will prevent students from becoming homesick and possibly reduce the dropout rate.[21]

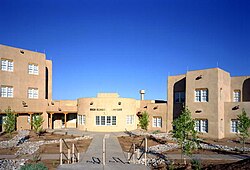

Today there are 624 students enrolled at SFIS in grades 7-12. Out of 624 students, 155 commute and 469 live in the dorms. The school is currently 54% girls and 46% boys. The Nineteen Pueblo Tribes were the most influential in the construction of the school; they made sure the architecture reflected their traditions and contained elements of typical Pueblo architecture. "A crucial factor in the project's success was sighting the school buildings to replicate a pueblo village while preserving views with religious significance… The buildings radiate out from a central plaza that is the focus of the site design".[21] The design was constructed with the intention of facilitating student comfort. The project had nineteen owners, each a governor of one of the Nineteen Pueblo Tribes. These owners had conflicting views of the project goals increasing the project difficulty, but enhancing the project's outcome. Joseph Abeyta, the Director of the SFIS at the time, believed that these new renovations were their chance to take back ownership of the school and what it represents. They would ensure the school "would reflect and sustain their culture".[21] These desires were fulfilled through the design of the project. The buildings were built in adobe style. The dorms and some classrooms contained fireplaces similar to the ones from their homes. SFIS has round rooms, to stimulate spirituality. These aspects tie together to produce the SFIS of today. With further construction and planning in the future, SFIS has a need to develop a reliable planning system.

Governance

editThere are 19 indigenous pueblos in the State of New Mexico these pueblos elect a board of seven members, and this board governs the school.[22]

Education goals of SFIS

editThe goals of SFIS are to educate the students by clarifying what they must accomplish, supported by an education of Native American culture as the foundation. "The Santa Fe Indian School remains a pivotal institution and educational training ground for the development of Indian students and their communities".[23] The strong relationship the school has with its tribal communities and parents is a fundamental aspect of the SFIS experience. With enhancing the educational experience and developing a new style of teaching, SFIS is looking to capitalize on the opportunities at hand and incorporate more technology into their plans.

Agriscience

editOne important initiative is a branch of CBE called Agriscience, which works closely with several Pueblo communities to engage students in all aspects of farming and agricultural practices through regular community visits. They learn about their culture and science while also practicing the design and management of sustainable agriculture systems.[24]

Senior honors project

editAnother branch of CBE is the Senior Honors Project (SHP). The SHP is designed to teach seniors necessary project skills in a way that helps their community address current problems. Victoria Atencio's SHP is a particularly relevant example. For her project, Honoring Mother Earth, she explored ways of reducing our impact on Earth by going back to traditional ways and focusing on renewable/alternative energy sources, enabling us to become a more sustainable community. She worked with the school's Green Team to teach her peers about more sustainable options.[25][26]

Campus

editThere is a dormitory for middle and high school students.[27]

References

edit- ^ "Santa Fe Indian School". National Center for Education Statistics. 2005–2006. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ "Our History". Santa Fe Indian School.

- ^ "Saturday, April 4". The Santa Fe New Mexican. 1885-04-04. Retrieved 2024-07-25 – via Newspapers.com.

Forty children at the Santa Fe Indian school in April 1885; 200 in April, 1887.

- ^ a b c d Santa Fe Indian School. (2011). About SFIS. Retrieved February 9, 2015, from Santa Fe Indian School: http://www.sfis.k12.nm.us/about_sfis

- ^ a b Santa Fe Indian School. (2011). Trust Responsibilities. Retrieved February 9, 2015, from Santa Fe Indian School: http://www.sfis.k12.nm.us/trust_responsibilities

- ^ a b c "Indian Boarding Schools | Indian Country Diaries". Native American Public Telecommunications | PBS. September 2006. Archived from the original on 2017-12-16.

- ^ Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction (1892), 46–59. Reprinted in Richard H. Pratt, "The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites," Americanizing the American Indians: Writings by the "Friends of the Indian" 1880–1900(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1973), 260–271.

- ^ Hunt, Darek. " BIA's Impact on Indian Education Is an Education in Bad Education." 30 Jan 2011. Retrieved 3 Nov 2013.

- ^ Hunt, Darek. "BIA's Impact on Indian Education Is an Education in Bad Education." 30 Jan 2011. Retrieved 3 Nov 2013.

- ^ a b 1819-2013: A History of American Indian Education. (2013, December 4). Retrieved February 28, 2015, from http://www.edweek.org/ew/projects/2013/native-american-education/history-of-american-indian-education.

- ^ The Meriam Report (1928) investigates failed U.S. Indian policy. (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2015, from http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/search.asp?id=952

- ^ Federal Indian Law For Alaska Tribes. Indian Reorganization Act (1934). Retrieved March 2, 2015 from TM112 Course Materials: https://tm112.community.uaf.edu/unit-2/indian-reorganization-act-1934/

- ^ Johnson-O'Malley Program Fact Sheet. (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2015, from http://ncidc.org/education/jomfactsheet

- ^ Collier, J. (1988). Survival At Rough Rock: A Historical Overview Of Rough Rock Demonstration School. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 19(3), 253-269.

- ^ "American Indian Education Foundation (AIEF) - providing support for Indian Education throughout the United States - American Indian Education Foundation". www.nativepartnership.org. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ^ "History of Indian Education - Office of Indian Education". Office of Elementary and Secondary Education | U.S. Department of Education. 2005-08-25. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ Manuelito, K. (2005, March). Anthropology & Education Quarterly. Indigenous Epistemologies and Education: Self-Determination, Anthropology, and Human Rights, 36, pp. 73-87.

- ^ Bernstein, Bruce, and W. Jackson Rushing. Modern by Tradition: American Indian Painting in the Studio Style. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1995: 9 and 14. ISBN 0-89013-291-7.

- ^ "Tonita Peña Pueblo Painter". Native American Art. 2010. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- ^ a b c d Wills, Eric (2008-12-15). "Santa Fe Indian School Razes 18 Buildings". Preservation Magazine. National Trust for Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on 2009-10-02. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ^ a b c Wendel, K. R. (2004, September 1). School Design Reflects Students' Culture. School Design Reflects Students' Culture, 66, 3.

- ^ Eichstaedt, Peter (1989-03-29). "'Not terminal'". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Santa Fe, New Mexico. p. A-3. - Clipping from Newspapers.com.

- ^ New Mexico State Record Center and Archives. (2010). Santa Fe Indian School. New Mexico, United States.

- ^ "Agriscience | Santa Fe Indian School". www.sfis.k12.nm.us.

- ^ "Seniors Honors Symposium | Santa Fe Indian School". www.sfis.k12.nm.us.

- ^ "Santa Fe Sustainable Santa Fe Website".

- ^ "Dorm students". Santa Fe Indian School. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

External links

edit- Official website

- The Santa Fe Review: A Special Report: The Mysterious Destruction of the Santa Fe Indian School

- Photo gallery at the Palace of the Governors state historical museum

- Santa Fe Indian Industrial School and Santa Fe Indian School Yearbooks and Early Newsletters from the collection of the Santa Fe Indian School Library and Archives, on the Indigenous Digital Archive