Internal bleeding (also called internal haemorrhage) is a loss of blood from a blood vessel that collects inside the body, and is not usually visible from the outside.[1] It can be a serious medical emergency but the extent of severity depends on bleeding rate and location of the bleeding (e.g. head, torso, extremities). Severe internal bleeding into the chest, abdomen, pelvis, or thighs can cause hemorrhagic shock or death if proper medical treatment is not received quickly.[2] Internal bleeding is a medical emergency and should be treated immediately by medical professionals.[2]

| Internal bleeding | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Internal hemorrhage |

| |

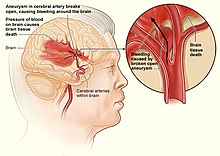

| Internal bleeding in the brain | |

| Complications | Hemorrhagic shock, hypovolemic shock, exsanguination |

Signs and symptoms

editSigns and symptoms of internal bleeding may vary based on location, presence of injury or trauma, and severity of bleeding. Common symptoms of blood loss may include:

- Lightheadedness

- Fatigue

- Urinating less than usual

- Confusion

- Fast heart rate

- Pale and/or cold skin

- Thirst

- Generalized weakness

Visible signs of internal bleeding include:

- Blood in the urine

- Dark black stools

- Bright red stools

- Bloody noses

- Bruising

- Throwing up blood

Of note, it is possible to have internal bleeding without any of the above symptoms, and pain may or may not be present. [3]

A patient may lose more than 30% of their blood volume before there are changes in their vital signs or level of consciousness.[4] This is called hemorrhagic or hypovolemic shock, which is a type of shock that occurs when there is not enough blood to reach organs in the body.[5]

Causes

editInternal bleeding can be caused by a broad number of things. We can break these up into three large categories:

- Trauma, or direct injury to blood vessels within the body cavity

- Genetic and acquired conditions, along with various medications, that result in an increased bleeding risk

- Other

Traumatic

editThe most common cause of death in trauma is bleeding.[6] Death from trauma accounts for 1.5 million of the 1.9 million deaths per year due to bleeding.[4]

There are two types of trauma: penetrating trauma and blunt trauma.[2]

- Penetrating trauma is the most common cause of vascular injury and can result in internal bleeding. It can occur after a ballistic injury or stab wound. If penetrating trauma occurs in blood vessels close to the heart, it can quickly lead to hemorrhagic or hypovolemic shock, exsanguination, and death.[2]

- Blunt trauma is another cause of vascular injury that can result in internal bleeding. It can occur after a high speed deceleration in an automobile accident.[2][7]

Non-traumatic

editA number of pathological conditions and diseases can lead to internal bleeding. These include:

- Blood vessel rupture as a result of high blood pressure, aneurysms, peptic ulcers, or ectopic pregnancy.[8]

- Other diseases linked to internal bleeding include cancer, hematologic disease, Vitamin K deficiency, and rare viral hemorrhagic fevers, such as the Ebola, Dengue or Marburg viruses.[9]

Other

editInternal bleeding could be a result of complications following surgery or other medical procedures. Some medications may also increase a person's risk for bleeding, such as anticoagulant drugs or antiplatelet drugs in the treatment of coronary artery disease.[10]

Diagnosis

editBlood loss can be estimated based on heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and mental status.[11] Blood is circulated throughout the body and all major organ systems through a closed loop system. When there is damage to the blood vessel or the blood is thinner than the physiologic consistency, blood can exit the vessel which disrupts this close-looped system. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) responds in two large ways as an attempt to compensate for the opening in the system. These two actions are easily monitored by checking the heart rate and blood pressure. Blood pressure will initially decrease due to the loss of blood. This is where the ANS comes in and attempts to compensate by contracting the muscles that surround these vessels. As a result, a person who is bleeding internally may initially have a normal blood pressure. When the blood pressure falls below the normal range, this is called hypotension. The heart will start to pump faster causing the heart rate to increase, as an attempt to get blood delivered to vital organ systems faster. When the heart beats faster than the healthy and normal range, this is called tachycardia. If the bleeding is not controlled or stopped, a patient will experience tachycardia and hypotension, which altogether is a state of shock, called hemorrhagic shock.

Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) by the American College of Surgeons separates hemorrhagic shock into four categories.[12][4][13]

| Estimated blood loss | Heart rate (per minute) | Blood pressure | Pulse pressure (mmHg) | Respiratory rate (per minute) | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I hemorrhage | < 15% | Normal or minimally elevated | Normal | Normal | Normal |

|

| Class II hemorrhage | 15 - 30% | 100 - 120 | Normal or minimally decreased systolic blood pressure | Narrowed | 20 - 30 |

|

| Class III hemorrhage | 30 - 40% | 120 - 140 | Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or change in blood pressure > 20-30% from presentation | Narrowed | 30 - 40 |

|

| Class IV hemorrhage | > 40% | > 140 | Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg | Narrowed (< 25 mmHg) | >35 |

|

Assessing circulation occurs after assessing the patient's airway and breathing (ABC (medicine)).[5] If internal bleeding is suspected, a patient's circulatory system is assessed through palpation of pulses and doppler ultrasonography.[2]

Physical examination

editIt is important to examine the person for visible signs that may suggest the presence of internal bleeding and/or the source of the bleed.[2] Some of these signs may include:

- a wound

- bruising [ecchymosis]

- blood collection [hematoma]

- abnormal skin sensation [paresthesia]

- signs of compartment syndrome

Imaging

editIf internal bleeding is suspected a FAST exam may be performed to look for bleeding in the abdomen.[2][12]

If the patient has stable vital signs, they may undergo diagnostic imaging such as a CT scan.[4] If the patient has unstable vital signs, they may not undergo diagnostic imaging and instead may receive immediate medical or surgical treatment.[4]

Treatment

editManagement of internal bleeding depends on the cause and severity of the bleed. Internal bleeding is a medical emergency and should be treated immediately by medical professionals.[2]

Fluid replacement

editIf a patient has low blood pressure (hypotension), intravenous fluids can be used until they can receive a blood transfusion. In order to replace blood loss quickly and with large amounts of IV fluids or blood, patients may need a central venous catheter.[12] Patients with severe bleeding need to receive large quantities of replacement blood via a blood transfusion. As soon as the clinician recognizes that the patient may have a severe, continuing hemorrhage requiring more than 4 units in 1 hour or 10 units in 6 hours, they should initiate a massive transfusion protocol.[12] The massive transfusion protocol replaces red blood cells, plasma, and platelets in varying ratios based on the cause of the bleeding (traumatic vs. non-traumatic).[4]

Stopping the bleeding

editIt is crucial to stop the internal bleeding immediately (achieve hemostasis) after identifying its cause.[4] The longer it takes to achieve hemostasis in people with traumatic causes (e.g. pelvic fracture) and non-traumatic causes (e.g. gastrointestinal bleeding, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm), the higher the death rate is.[4]

Unlike with external bleeding, most internal bleeding cannot be controlled by applying pressure to the site of injury.[12] Internal bleeding in the thorax and abdominal cavity (including both the intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal space) cannot be controlled with direct pressure (compression). A patient with acute internal bleeding in the thorax after trauma should be diagnosed, resuscitated, and stabilized in the Emergency Department in less than 10 minutes before undergoing surgery to reduce the risk of death from internal bleeding.[4] A patient with acute internal bleeding in the abdomen or pelvis after trauma may require use of a REBOA device to slow the bleeding.[4] The REBOA has also been used for non-traumatic causes of internal bleeding, including bleeding during childbirth and gastrointestinal bleeding.[4]

Internal bleeding from a bone fracture in the arms or legs may be partially controlled with direct pressure using a tourniquet.[12] After tourniquet placement, the patient may need immediate surgery to find the bleeding blood vessel.[4]

Internal bleeding where the torso meets the extremities ("junctional sites" such as the axilla or groin) cannot be controlled with a tourniquet; however there is an FDA approved device known as an Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet (AAJT) designed for proximal aortic control, although very few studies examining its use have been published.[14][15][16][17][18][19] For bleeding at junctional sites, a dressing with a blood clotting agent (hemostatic dressing) should be applied.[4]

A campaign is to improve the care of the bleeding known as Stop The Bleed campaign is also taking place.[20]

References

edit- ^ Auerback, Paul. Field Guide to Wilderness Medicine (PDF) (12 ed.). pp. 129–131. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fritz, Davis (2011). "Vascular Emergencies". Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Emergency Medicine (7e ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071701075.

- ^ "DynaMed". www.dynamed.com. Retrieved 2023-10-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Cannon, Jeremy (January 25, 2018). "Hemorrhagic Shock". The New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (4): 370–379. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1705649. PMID 29365303. S2CID 205117992.

- ^ a b International Trauma Life Support for Emergency Care Providers. Pearson Education Limited. 2018. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-1292-17084-8.

- ^ Teixeira, Pedro G. R.; Inaba, Kenji; Hadjizacharia, Pantelis; Brown, Carlos; Salim, Ali; Rhee, Peter; Browder, Timothy; Noguchi, Thomas T.; Demetriades, Demetrios (December 2007). "Preventable or Potentially Preventable Mortality at a Mature Trauma Center". The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 63 (6): 1338–46, discussion 1346–7. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31815078ae. PMID 18212658.

- ^ Duncan, Nicholas S.; Moran, Chris (2010). "(i) Initial resuscitation of the trauma victim". Orthopaedics and Trauma. 24: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.mporth.2009.12.003.

- ^ Lee, Edward W.; Laberge, Jeanne M. (2004). "Differential Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Bleeding". Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 7 (3): 112–122. doi:10.1053/j.tvir.2004.12.001. PMID 16015555.

- ^ Bray, M. (2009). "Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses". Encyclopedia of Microbiology. pp. 339–353. doi:10.1016/B978-012373944-5.00303-5. ISBN 9780123739445.

- ^ Pospíšil, Jan; Hromádka, Milan; Bernat, Ivo; Rokyta, Richard (2013). "STEMI - the importance of balance between antithrombotic treatment and bleeding risk". Cor et Vasa. 55 (2): e135–e146. doi:10.1016/j.crvasa.2013.02.004.

- ^ Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Emergency Medicine. McGraw-Hill. 2011-05-23. ISBN 978-0071701075.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colwell, Christopher. "Initial management of moderate to severe hemorrhage in the adult trauma patient". UpToDate. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ a b ATLS- Advanced Trauma Life Support - Student Course Manual (10th ed.). American College of Surgeons. 2018. pp. 43–52. ISBN 978-78-0-9968267.

- ^ Croushorn J. Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet controls hemor-rhage from a gunshot wound of the left groin.JSpecOperMed.2014;14(2):6–8.

- ^ Croushorn J, Thomas G, McCord SR. Abdominal aortic tourniquet controlsjunctional hemorrhage from a gunshot wound of the axilla.J Spec Oper Med.2013;13(3):1–4.

- ^ Rall JM, Ross JD, Clemens MS, Cox JM, Buckley TA, Morrison JJ. Hemo-dynamic effects of the Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet in ahemorrhagic swine model.JSurgRes. 2017;212:159–166.

- ^ Kheirabadi BS, Terrazas IB, Miranda N, Voelker AN, Grimm R, Kragh JF Jr,Dubick MA. Physiological Consequences of Abdominal Aortic and Junc-tional Tourniquet (AAJT) application to control hemorrhage in a swinemodel.Shock (Augusta, Ga). 2016;46(3 Suppl 1):160–166.

- ^ Taylor DM, Coleman M, Parker PJ. The evaluation of an abdominal aortictourniquet for the control of pelvic and lower limb hemorrhage.Mil Med.2013;178(11):1196–1201.

- ^ Brannstrom A., Rocksen D., Hartman J., et al Abdominal aortic and junctional tourniquet release after 240 minutes is survivable and associated with small intestine and liver ischemia after porcine class II hemorrhage. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg.. 2018;85(4):717-724. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002013

- ^ Pons, MD, Peter. "Stop the Bleed - SAVE A LIFE: What Everyone Should Know to Stop Bleeding After an Injury".[permanent dead link]