Sunitinib, sold under the brand name Sutent, is an anti-cancer medication.[2] It is a small-molecule, multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor that was approved by the FDA for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in January 2006. Sunitinib was the first cancer drug simultaneously approved for two different indications.[3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sutent, others |

| Other names | SU11248 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607052 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Unaffected by food |

| Protein binding | 95% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 40 to 60 hours (sunitinib) 80 to 110 hours (metabolite) |

| Excretion | Fecal (61%) and kidney (16%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL |

|

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

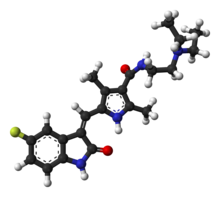

| Formula | C22H27FN4O2 |

| Molar mass | 398.482 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

As of August 2021, sunitinib is available as a generic medicine in the US.[4]

Medical uses

editGastrointestinal stromal tumor

editLike renal cell carcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors do not generally respond to standard chemotherapy or radiation. Imatinib was the first chemotherapeutic agent proven effective for metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors and represented a significant development in the treatment of this rare but challenging disease. However, approximately 20% of patients do not respond to imatinib (early or primary resistance), and among those who do respond initially, 50% develop secondary imatinib resistance and disease progression within two years. Before sunitinib, patients had no therapeutic option once they became resistant to imatinib.[5]

Sunitinib offers patients with imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors a new treatment option to stop further disease progression and, in some cases, even reverse it. This was shown in a large phase III clinical trial in which patients who failed imatinib therapy (due to primary or secondary resistance or intolerance) were treated in a randomized and blinded fashion with either sunitinib or placebo.[5]

The study was unblinded early—at the first interim analysis—due to the clearly emerging benefit of sunitinib. Patients receiving a placebo were offered to switch to sunitinib at that time. In the primary endpoint of the study, the median time to tumor progression (TTP) was more than four-fold longer with sunitinib (27 weeks) compared with placebo (six weeks, P<.0001), based on an independent radiological assessment. The benefit of sunitinib remained statistically significant when stratified by many prespecified baseline variables.[5]

Among the secondary endpoints, the difference in progression-free survival (PFS) was similar to that in TTP (24 weeks vs. six weeks, P<.0001). Seven percent of sunitinib patients had significant tumor shrinkage (objective response) compared to 0% of patients receiving placebo (P=.006). Another 58% of sunitinib patients had disease stabilization vs. 48% of patients receiving placebo. The median time to response with sunitinib was 10.4 weeks.[5] Sunitinib reduced the relative risk of disease progression or death by 67% and the risk of death alone by 51%. The difference in survival benefit may be diluted because placebo patients crossed over to sunitinib upon disease progression, and most of these patients subsequently responded to sunitinib.[5]

Sunitinib was relatively well tolerated. About 83% of sunitinib patients experienced a treatment-related adverse event of any severity, as did 59% of patients who received placebo. Serious adverse events were reported in 20% of sunitinib patients and 5% of placebo patients. Adverse events were generally moderate and easily managed by dose reduction, dose interruption, or other treatment. Nine percent of sunitinib patients and 8% of placebo patients discontinued therapy due to an adverse event.[5]

Fatigue is the adverse event most commonly associated with sunitinib therapy. In this study, 34% of sunitinib patients reported any fatigue, compared with 22% for placebo. The grade 3 (severe) fatigue incidence was similar between the two groups, and no grade 4 fatigue was reported.[5]

Meningioma

editSunitinib is being studied for the treatment of meningioma, which is associated with neurofibromatosis.[6]

Aggressive fibromatosis

editAs of 2024[update], sunitinib is being studied for aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumors).[7]

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

editIn November 2010, Sutent gained approval from the European Commission for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic, well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with disease progression in adults.[8] In May 2011, the USFDA approved Sunitinib for treating patients with 'progressive neuroendocrine cancerous tumors located in the pancreas that cannot be removed by surgery, or that has spread to other parts of the body (metastatic).[9]

Renal cell carcinoma

editSunitinib is approved for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Other therapeutic options in this setting are pazopanib (Votrient), sorafenib (Nexavar), temsirolimus (Torisel), interleukin-2 (Proleukin), everolimus (Afinitor), bevacizumab (Avastin), and aldesleukin.

Renal cell carcinoma is generally resistant to chemotherapy or radiation. Before RTKs, metastatic disease could only be treated with the cytokines interferon alpha (IFNα) or interleukin-2. However, these agents demonstrated low rates of efficacy (5%-20%).

In a phase III study, median progression-free survival was significantly longer in the sunitinib group (11 months) than in the IFNα group (five months), with a hazard ratio of 0.42.[2][10] In the secondary endpoints, 28% had significant tumor shrinkage with sunitinib compared to 5% with IFNα. Patients receiving sunitinib had a better quality of life than IFNα. An update in 2008 showed that the primary endpoint of median progression-free survival (PFS) remained superior with sunitinib: 11 months versus 5 months for IFNα, P<.000001. Objective response rate also remained superior: 39-47% for sunitinib versus 8-12% with IFNα, P<.000001.[11][12]

Sunitinib treatment trended towards a slightly longer overall survival, although this was not statistically significant.

- Median overall survivability was 26 months with sunitinib vs 22 months for IFNα regardless of stratification (P-value ranges from .051 to .0132, depending on statistical analysis).

- The first analysis includes 25 patients initially randomized to IFNα who crossed over to sunitinib therapy, which may have confounded the results; in an exploratory analysis that excluded these patients, the difference becomes more robust: 26 vs 20 months, P=.0081.

- Patients in the study were allowed to receive other therapies once they had progressed on their study treatment. For a "pure" analysis of the difference between the two agents, an analysis was done using only patients who did not receive any post-study treatment. This analysis demonstrated the greatest advantage for sunitinib: 28 months vs 14 months for IFNα, P=.0033. The number of patients in this analysis was small, which does not reflect actual clinical practice; therefore, it is not meaningful.

Hypertension (HTN) was found to be a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib.[13] Patients with mRCC and sunitinib-induced hypertension had better outcomes than those without treatment-induced HTN.

Mechanism of action

editSunitinib inhibits cellular signalling by targeting multiple receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs).

These include all receptors for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-Rs) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs), which play a role in both tumor angiogenesis and tumor cell proliferation. The simultaneous inhibition of these targets therefore reduces tumor vascularization and triggers cancer cell apoptosis and thus results in tumor shrinkage.

Sunitinib also inhibits CD117 (c-KIT),[14] the receptor tyrosine kinase that (when improperly activated by mutation) drives the majority of gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors.[15] It has been recommended as a second-line therapy for patients whose tumors develop mutations in c-KIT that make them resistant to imatinib, or who the cannot tolerate the drug.[16][17]

In addition, sunitinib binds other receptors.[2] These include:

The fact that sunitinib targets many different receptors, leads to many of its side effects such as the classic hand-foot syndrome, stomatitis, and other dermatologic toxicities.

History

editThe drug was discovered at SUGEN, a biotechnology company which pioneered protein kinase inhibitors. It was the third in a series of compounds including SU5416 and SU6668. The concept was of an ATP mimic that would compete with ATP for binding to the catalytic site of receptor tyrosine kinases. This concept led to the invention of many small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors, including Gleevec, Sutent, Tarceva and many others. [citation needed]

Side effects

editSunitinib adverse events are considered somewhat manageable and the incidence of serious adverse events low.[5][10]

The most common adverse events associated with sunitinib therapy are fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, hypertension, a yellow skin discoloration, hand-foot skin reaction, and stomatitis.[18] In the placebo-controlled Phase III GIST study, adverse events which occurred more often with sunitinib than placebo included diarrhea, anorexia, skin discoloration, mucositis/stomatitis, asthenia, altered taste, and constipation.[2][5]

Serious (grade 3 or 4) adverse events occur in ≤10% of patients and include hypertension, fatigue, asthenia, diarrhea, and chemotherapy-induced acral erythema. Lab abnormalities associated with sunitinib therapy include lipase, amylase, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets. Hypothyroidism and reversible erythrocytosis have also been associated with sunitinib.[2][19]

A study done at MD Anderson Cancer Center compared the outcomes of metastatic renal cell cancer patients who received sunitinib on the standard schedule (50 mg/4 weeks on 2 weeks off) with those who received sunitinib with more frequent and short drug holidays (alternative schedule). It was seen that the overall survival, progression free survival and drug adherence were significantly higher in the patients who received Sunitinib on the alternative schedule. Patients also had a better tolerance and lower severity of adverse events which frequently lead to discontinuation of treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer patients.[20]

Interactions

editEpigallocatechin-3-gallate, a major constituent of green tea, may reduce the bioavailability of sunitinib when they are taken together.[21]

Society and culture

editEconomics

editSunitinib is marketed by Pfizer as Sutent, and was subject to patents and market exclusivity as a new chemical entity until 15 February 2021.[22][23] Sutent has been cited in financial news as a potential revenue source to replace royalties lost from Lipitor following the expiration of the latter drug's patent expiration in November 2011.[24][25] Sutent is one of the most expensive drugs widely marketed.[citation needed] Doctors and editorials have criticized the high cost for a drug that does not cure cancer, but only prolongs life.

US

editIn the U.S., many insurance companies[which?] have refused to pay for all or part of the costs of Sutent. Because it is an oral therapy, the copay associated with this therapy can be very substantial. If a patient's secondary insurance does not cover this, the cost burden to the patient can be extreme. Particularly challenging is the Medicare Part D coverage gap. Patients have to spend thousands of dollars out-of-pocket during the gap in coverage. If this is done at the end of a calendar year, it has to be paid again at the beginning of the next calendar year, which may be burdensome financially.

UK

editIn the UK, NICE refused (late 2008) to recommend sunitinib for late-stage renal cancer (kidney cancer) due to the high cost per QALY, estimated by NICE at £72,000/QALY and by Pfizer at £29,000/QALY.[26][27] This was overturned in February 2009 after pricing changes and public responses.[28] Therefore, sunitinib is recommended as a first-line treatment option for people with advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma who are suitable for immunotherapy and have an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 (i.e. completely ambulatory).[29]

AU

editSunitinib is available in Australia and is subsidized by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme for Stage IV Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC). The cost to the patient who meets the clinical criteria of Stage IV RCC is AUD $35.40 for 28 capsules, regardless of dose. Manufacturer pricing for sunitinib ranges from AUD $1,834.30 to AUD $6897.54, depending on dose (12.5 mg to 50 mg).[30]

Research

editOther solid tumors

editThe efficacy of sunitinib is currently being evaluated in a broad range of solid tumors, including breast, lung, thyroid and colorectal cancers. Early studies have shown single-agent efficacy in a number of different areas. Sunitinib blocks the tyrosine kinase activities of KIT, PDGFR, VEGFR2 and other tyrosine kinases involved in the development of tumours.

- A Phase II study in previously treated patients with metastatic breast cancer found sunitinib “has significant single agent activity”.[31]

- A phase II study of refractory non-small-cell lung cancer found “Sunitinib has provocative single-agent activity in previously treated pts with recurrent and advanced NSCLC, with the level of activity similar to currently approved agents.” [32]

- In a phase II study of patients with nonresectable neuroendocrine tumors, 91% of patients responded to sunitinib (9% partial response + 82% stable disease).[33]

- Sunitinib was found to protect JIMT-1 breast cancer cells against natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, which was claimed to block the anticancer immune response. If sunitinib were to be paired with anticancer immunotherapies, this finding might need to be taken into account.[34]

Leukemia

editSunitinib was used to treat the leukemia of a Washington University in St. Louis leukemia researcher who developed the disease himself. His team used genetic sequencing and noticed that the FLT3 gene was hyperactive in his leukemia cells and used sunitinib as a treatment.[35]

Unsuccessful trials

editBetween April 2009 and May 2011, Pfizer has reported unsuccessful late-stage trials in breast cancer, metastatic colorectal cancer, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer, and castration-resistant prostate cancer.[36]

References

edit- ^ "SUNITINIB MSN sunitinib (as malate) 50 mg hard capsule bottle (Accelagen Pty Ltd)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 28 September 2022. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sutent- sunitinib malate capsule". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "FDA approves new treatment for gastrointestinal and kidney cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2006. Archived from the original on 3 February 2006.

- ^ "Sunitinib malate: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, Blackstein ME, Shah MH, Verweij J, et al. (October 2006). "Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 368 (9544): 1329–1338. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. PMID 17046465. S2CID 25931515.

- ^ "Phase II Trial of Sunitinib (SU011248) in Patients With Recurrent or Inoperable Meningioma". 21 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023 – via clinicaltrials.gov.

- ^ Mangla A, Agarwal N, Schwartz G (February 2024). "Desmoid Tumors: Current Perspective and Treatment". Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 25 (2): 161–175. doi:10.1007/s11864-024-01177-5. PMC 10873447. PMID 38270798.

- ^ "Pfizer Scores New Approval for Sutent in Europe". 2 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ "FDA approves Sutent for rare type of pancreatic cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 20 May 2011. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ a b Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, et al. (January 2007). "Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (2): 115–124. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa065044. PMID 17215529.

- ^ Figlin RA, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Négrier S, et al. (2008). "Overall survival with sunitinib versus interferon (IFN)-alfa as first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 26 (15_suppl): 5024. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.5024. Abstract no. 5024. Presented at ASCO 2008.

- ^ Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Oudard S, et al. (August 2009). "Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 27 (22): 3584–3590. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293. PMC 3646307. PMID 19487381.

- ^ "Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. | CureHunter". www.curehunter.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Hartmann JT, Kanz L (November 2008). "Sunitinib and periodic hair depigmentation due to temporary c-KIT inhibition". Archives of Dermatology. 144 (11): 1525–1526. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.11.1525. PMID 19015436.

- ^ Quek R, George S (February 2009). "Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a clinical overview". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 23 (1): 69–78, viii. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.11.006. PMID 19248971.

- ^ Blay JY, Reichardt P (June 2009). "Advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor in Europe: a review of updated treatment recommendations". Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 9 (6): 831–838. doi:10.1586/era.09.34. PMID 19496720. S2CID 23601578.

- ^ Gan HK, Seruga B, Knox JJ (June 2009). "Sunitinib in solid tumors". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 18 (6): 821–834. doi:10.1517/13543780902980171. PMID 19453268. S2CID 25353839.

- ^ Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT, Dutcher J (March 2007). "Yellow skin discoloration associated with sorafenib use for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma". Southern Medical Journal. 100 (3): 328–330. doi:10.1097/smj.0b013e31802f01a9. PMID 17396743. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ Alexandrescu DT, McClure R, Farzanmehr H, Dasanu CA (August 2008). "Secondary erythrocytosis produced by the tyrosine kinase inhibitors sunitinib and sorafenib". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 26 (24): 4047–4048. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.18.3525. PMID 18711201.

- ^ Atkinson BJ, Kalra S, Wang X, Bathala T, Corn P, Tannir NM, et al. (March 2014). "Clinical outcomes for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with alternative sunitinib schedules". The Journal of Urology. 191 (3): 611–618. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2013.08.090. PMC 4015627. PMID 24018239.

- ^ Ge J, Tan BX, Chen Y, Yang L, Peng XC, Li HZ, et al. (June 2011). "Interaction of green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate with sunitinib: potential risk of diminished sunitinib bioavailability". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 89 (6): 595–602. doi:10.1007/s00109-011-0737-3. PMID 21331509. S2CID 8334011.

- ^ "Patent and Exclusivity Search Results from query on Appl No 021938 Product 003 in the OB_Rx list". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2009. Sutent is subject to US patent 7211600 (expires 22 December 2020), 7125905 and 6573293 (expire 15 February 2021). Note that this information does not include or predict patent extensions.

- ^ "Details for Generic 'SUNITINIB MALATE'". DrugPatentWatch. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Jamie Dlugosch (13 March 2009). "Will biologics and Sutent save Pfizer?". InvestorPlace. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ Zacks Investment Research (22 March 2007). "Pfizer's a Sell: Shrinking Top Line, No Blockbusters In the Pipeline". Seeking Alpha. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ BMJ 31 January 2009 "NICE and the challenge of cancer drugs" p.271.[full citation needed]

- ^ "'We'll sell our house for this drug'". BBC News. 7 August 2008. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Devlin K (24 May 2010). "Kidney cancer patients should get Sutent on the NHS, says NICE". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Renal cancer". pathways.nice.org.uk. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS)". Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023 – via www.pbs.gov.au.

- ^ Miller KD, Burstein HJ, Elias AD, Rugo HS, Cobleigh MA, Pegram MD, et al. "Phase II study of SU11248, a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer". Presented at ASCO 2005. Abstract No: 563. Archived from the original on 25 August 2007.

- ^ Socinski MA, Novello S, Sanchez JM, Brahmer JA, Govindan R, Belani CP, et al. (2006). "Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in previously treated, advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): preliminary results of a multicenter phase II trial". Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2006 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. 24 (18S: 20 June suppl). Abstract No: 7001. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008.

- ^ Kulke M, Lenz HJ, Meropol NJ, Posey J, Ryan DP, Picus J, et al. "A Phase 2 Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of SU11248 in Patients with Unresectable Neuroendocrine Tumors". Presented at ASCO 2005. Abstract No: 4008. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006.

- ^ Guti E, Regdon Z, Sturniolo I, Kiss A, Kovács K, Demény M, et al. (September 2022). "The multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib induces resistance of HER2 positive breast cancer cells to trastuzumab-mediated ADCC". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 71 (9): 2151–2168. doi:10.1007/s00262-022-03146-z. PMC 9374626. PMID 35066605.

- ^ Kolata G (7 July 2012). "In Gene Sequencing Treatment for Leukemia, Glimpses of the Future". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "FDA Expands Sutent Label to Include Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors". GEN - Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

External links

edit- "Sunitinib". National Cancer Institute.