This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 30,000 words. (June 2023) |

The "swan maiden" story is a name in folkloristics used to refer to three kinds of stories: those where one of the characters is a bird-maiden, in which she can appear either as a bird or as a woman; those in which one of the elements of the narrative is the theft of the feather-robe belonging to a bird-maiden, though it is not the most important theme in the story; and finally the most commonly referred to motif, and also the most archaic in origin: those stories in which the main theme, among several mixed motifs, is that of a man who finds the bird-maiden bathing and steals her feathered robe, which leads to him becoming married to the bird-maiden. Later, the maiden recovers the robe and flies away, returning to the sky, and the man may seek her again.[1][2] It is one of the most widely distributed motifs in the world, most probably being many millennia old,[1][2][3] and the best known supernatural wife figure in narratives.[4]

It also belongs to the larger motif of the "Magic Wife",[3] pertaining to the index category ATU 400, "The Man on a Quest for His Lost Wife", where the man makes a pact with a supernatural female creature, which later departs.[2] This category is one of the most interconnected and centrally referred to among all the other stories, for instance along with the Dragonslayer motif.[2][5] More generally, it is also called the bird-maiden or sky-maiden motif, since not always they are swans: the properly called swan maiden appear in stories of the northernmost regions, in which they are part of a group where the bird-maidens are migratory birds, among other variants, such as the goose, duck, crane and heron. The sky-maiden may also appear in other stories as doves, non-migratory birds, and also as stars or celestial nymphs.[1][2][3]

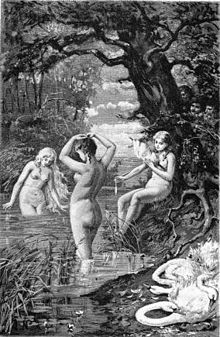

The literal swan maiden character in particular is a mythical creature who shapeshifts from human form to swan form.[6] The key to the transformation is usually a swan skin, or a garment with swan feathers attached.[7][8] In folktales of this type, the male character spies the maiden, typically by some body of water (usually bathing), then snatches away the feather garment (or some other article of clothing), which prevents her from flying away (or swimming away, or renders her helpless in some other manner), forcing her to become his wife.[9]

There are parallels around the world, notably the Völundarkviða[10] and Grimms' Fairy Tales KHM 193 "The Drummer".[9] There are also many parallels involving creatures other than swans.

General overview in folkloristics

editMyths are adapted with the elements found in the local context of each culture, frequently undergoing subtle changes, while preserving most of the original structure or main prototypical elements. Thus, all the versions where the sky-maiden is a migratory bird are mostly found in northernmost regions, whereas more to the South, the women of the tale are more commonly non-migratory birds, and may also be stars or celestial nymphs. Also in the southernmost regions, differently from the North ones, the sky-maiden stories generally have anthropogonic or ethiological value, explaining the origin of humans, cultures, gods, celestial phenomena.[2]

The areal study of the Swan Maiden myth first began in 1894, with Hyacinthe de Charencey.[2] The proposal of its origins in India by Theodor Benfey and the Finnish school has been discredited a long time ago.[1]

Bo Almqvist considers that there was a time in the past that it was ubiquitious the belief that "certain zoomorphic or semi-zoomorphic beings – whether expressly stated to be enchanted humans or not – are able to remove their animal coats and take human shape". In an analysis by Almqvist of the 1919 thesis of Helge Holmström on the Swan Maiden motif, he says that: "the Swan Maiden Legend is but one of a whole complex of migratory legends relating to marriages to supernatural or supernaturally transformed female beings", and that one other such group includes that of aquatic beings, such as mermaids; there are similarities between sky-maiden and sea-maiden stories.[11]

Arthur T. Hatto connects the origin of the bird-maiden motif with the migration and mating of migratory aquatic-related bird (swans included), and local totemic and shamanistic conceptions, such as the possible notions of foreign women (with the analogy of the migratory birds) being related to sorcery; the husband undertaking labours and challenges in his search journey; or an analogy for the soul flight.[1]

Yuri Berezkin affirms that this motif might have appeared first in Asia, diffusing to the New World, and that a novel ecotype later arrived at North Eurasia and again was brought to North America, c. 5000 BC. Julien d’Huy identified the presence of the bird-maiden story also in six linguistically isolated groups: the Ainus, the Basques, the Burusho, the Koreans, the Cofán, the Haida, the Tlingit and the Natchez. Based on the cladistics of the mythemes, he obtained statistical evidence that agrees with the proposal of Berezkin that the motif arrived in the Americas in two different times. He thus reconstructed the protomyth (with more than 75% chance) as appearing first in East Asia following this structure:[2]

"The hero, a young man, a good hunter, surprises women bathing in a lake. They have retained their appearance as immortals or supernatural creatures. They undress and their bodies or clothes are covered with feathers. The hero seizes the clothes or the plumage of the most beautiful woman, but does not hide them. The naked woman asks the hero to give her back her outfit. She promises [in exchange] to marry him. They first live in the hero's world. One day, the woman puts on her old plumage and, after living on earth, returns to heaven. The man tries to find her. He performs several difficult and dangerous tasks, and his quest ends happily, with a reunion with his wife. However, at the end of the story, the hero lives alone or returns home alone."

The researcher also points out that, among the hundreds of other categories of motifs, the bird-maiden motif belongs to a core group (ATU 400):[2]

"The different types, or set of types, therefore seem linked by a very small number of intermediate stories. These stories therefore seem more important than others in the economy of narration, probably acting for storytellers as a mental intermediary or a “highway interchange” between distinct groups of story-types. The cultural success and the area of diffusion of the tale-types do not seem to explain the centrality of the stories, but they all share the property of being probably extremely old, as if the flesh of our folklore had grown on a bone frame much older than that."

Legend

editTypical legend

editThe folktales usually adhere to the following basic plot. A young, unmarried man steals a magic robe made of swan feathers from a swan maiden who comes to bathe in a body of water, so that she will not fly away, and marries her. Usually she bears his children. When the children are older they sing a song about where their father has hidden their mother's robe, or one asks why the mother always weeps, and finds the cloak for her, or they otherwise betray the secret. The swan maiden immediately gets her robe and disappears to where she came from.[12][13][14][15] Although the children may grieve her, she does not take them with her.[16]

If the husband is able to find her again, it is an arduous quest, and often the impossibility is clear enough so that he does not even try.

In many versions, although the man is unmarried (or, very rarely, a widower), he is aided by his mother, who hides the maiden's magical garment (or feather cloak). At some point later in the story, the mother is convinced or forced to give back the hidden clothing and, as soon as the swan maiden puts it on, she glides towards the skies – which prompts the quest.

Alternate openings

editRomanian folklorist Marcu Beza drew attention to two other introductory episodes: (1) seven white birds steal the golden apples from a tree in the king's garden (an episode similar to German The Golden Bird), or, alternatively, they come and trample the fields; (2) the hero receives a key and, against his master's wishes, opens a forbidden chamber, where the bird maidens are bathing.[17]

Researcher Barbara Fass Leavy noted a variation of the first opening episode - described above -, which occurs in Scandinavian tales: a man's third or only son stands guard on his father's fields at night to discover what has been trampling his father's fields, and sees three maidens dancing in a meadow.[18]

As for the second episode, it may be known as "The Forbidden Chamber", in folkloristic works.[19] Edwin Sidney Hartland indicated the occurrence of the second opening episode in tales from Arabic folklore.[20]

Germanic legend

editIn Germanic mythology, the character of the swan maiden is associated with "multiple Valkyries",[21] a trait already observed by Jacob Grimm in his book Deutsche Mythologie (Teutonic Mythology).[22] Like the international legend, their magic swan-shirt allows their avian transformation.[23]

In Germanic heroic legend, the stories of Wayland the Smith describe him as falling in love with Swanhilde, a Swan Maiden, who is the daughter of a marriage between a mortal woman and a fairy king, who forbids his wife to ask about his origins; on her asking him he vanishes. Swanhilde and her sisters are however able to fly as swans. But wounded by a spear, Swanhilde falls to earth and is rescued by the master-craftsman Wieland, and marries him, putting aside her wings and her magic ring of power. Wieland's enemies, the Neidings, under Princess Bathilde, steal the ring, kidnap Swanhilde and destroy Wieland's home. When Wieland searches for Swanhilde, they entrap and cripple him. However he fashions wings for himself and escapes with Swanhilde as the house of the Neidings is destroyed.

Another tale concerns valkyrie Brynhild.[24] In the Völsunga saga, King Agnar withholds Brynhild's magical swan shirt, thus forcing her into his service as his enforcer.[25]

A third tale with a valkyrie is the story of Kára and Helgi Haddingjaskati, attested in the Kara-lied.[26][27] A similarly named character with a swanshift appears in Hrómundar saga Gripssonar, where she helps her lover Helgi.[28][22]

Swan maiden as daughter or servant to an antagonist

editThe second type of tale that involves the swan maiden is type ATU 313, "The Magic Flight", where the character helps the hero against an antagonist.[29] It can be the maiden's mistress, e. g., a witch, as in a tale published by illustrator Howard Pyle in The Wonder Clock,[30] or the maiden's father, e. g., the character of Morskoi Tsar in Russian fairy tales.[31][32] In this second format, the hero of the tale spies on the bird (swan) maidens bathing and hides the garment (featherskin) of the youngest one, for her to help him reach the kingdom of the villain of the tale (usually the swan-maiden's father).[33][34]

In the Scottish story titled "The Tale of the Son of the King of Ireland and the Daughter of the King of the Red Cap" (Scottish Gaelic: Sgeulachd air Mac Righ Éirionn agus Nighean Rígh a' Churraichd Ruaidh), the prince of Ireland falls in love with the White Swan of the Smooth Neck, also called Sunshine, the young daughter of the King of the Red Cap, as he saw her coming to bathe in a lake.[35]

In a Flemish fairy tale, Het zwanenmeisje van den glazen berg ("The Swan Maiden of the Glass Mountain"), a young hunter fetches the swan garment of a bathing maiden, who asks for it in return. When she wears it, she tells the hunter to find her in the Glass Mountain. After he succeeds in climbing the mountain, the youth recognizes his beloved swan maiden and asks her mother for her daughter's hand in marriage. The mother assures the human he will be able to marry her daughter, after doing three difficult chores.[36]

In an Evenk tale titled The Grateful Eagle, the hero is promised to an old man after he helped the hero's father close a magical casket. Years later, the hero finds three swan maidens bathing in the river and fetches the robe of one of them. She insists the boy returns it and tells him to pay a visit to her village, where the old man also lives. Soon after arriving, he goes to the old man's house and is attended by "a pretty maid", later revealed to be the old man's granddaughter.[37]

Other fiction

editThe swan maiden has appeared in numerous items of fiction.

In legend

editIn a Tatar poem, there appears the character of The Swan-Women, Tjektschäkäi, who develops an inimical relationship with hero Kartaga Mergän.[38][39][40]

19th century folkloristic publications mentioned a tale about Grace's Well, a well whose caretaker's carelessness led her to be turned into a swan by the fairies. The well was reported to be near Glasfryn lake, somewhere in Wales.[41][42]

In a Russian byliny or heroic poem, a character named White Swan (Byelaya Lebed'), whose real name may be Avdotya or Marya, appears as the traitorous love interest of the hero.[39]

In folklore

editScholarship has remarked that the Swan Maiden appears "throughout the ancient Celtic lands".[43]

On the other hand, researcher Maria Tatar points out that the "Swan Maiden" tale is "widespread in Nordic regions".[44]

Scholar Lotte Motz contrasted its presence in different geographical regions. According to her study, she appears as a fairy tale character in "more southern countries", whereas "in northern regions", she becomes a myth and "an element of faith".[45]

In Celtic traditions

editPatricia Monaghan stated the swan maiden was an "Irish, Scottish and a continental Celtic folkloric figure",[43] appearing, for instance, in Armorica.[46]

British folklorist Katharine Mary Briggs, while acknowledging the universality of the tale, suggested the character seemed more prevalent in the Celtic fairy tale tradition of the British Islands.[47] She claimed in the introduction to fellow British folklore collector and writer Ruth Tongue's book that "variants [of the Swan Maiden tale] are common in Wales".[48]

In the same vein, William Bernard McCarthy reported that in Irish tradition the tale type ATU 400 ("Swan Maiden") is frequently merged with ATU 313 ("The Master Maid", "The Magical Flight", "The Devil's Daughter").[49] In that regard, Norwegian folklorist Reidar Thoralf Christiansen suggested that the presence of the Swan maiden character in tale type ATU 313 "could be explained by the circumstance that in both cycles a woman with supernatural powers plays a leading part".[34]

In addition, Celticist Tom Peete Cross concluded that the swan maiden "figured in Celtic literature before the twelfth century", although, in this tradition, she was often confused for similar supernatural women, i.e., the Celtic fairy-princess, the forth-putting fée and the water-fée.[50]

In Irish Sagas

editThe swan is said to be the preferred form adopted by Celtic goddesses. Even in this form, their otherworldly nature is identifiable by a golden or silver chain hanging around their neck.[51]

In the Irish Mythological Cycle of stories, in the tale of The Wooing of Étaine, a similar test involving the recognition of the wife among lookalikes happens to Eochu Airem, when he has to find his beloved Étaine, who flew away in the shape of a swan.[52]

A second Irish tale of a maiden changing into a swan is the story of hero Óengus, who falls in love with Caer Ibormeith, in a dream. When he finds her, Caer is in swan form, wearing a golden chain, and accompanied by 150 maidservants also in swan form, each pair bound with a silver chain.[53]

In another tale, relating to the birth of hero Cú Chulainn, a flock of birds, "joined in pairs by silver chains", appear and guide the Ulstermen to a house, where a woman was about to give birth. In one account, the birds were Cu Chulainn's mother, Deichtire, and her maidens.[54]

Irish folklore

editIn a Scottish tale (Scottish Gaelic: Mac an Tuathanaich a Thàinig a Raineach, lit. 'The Farmer's son who came from Rannoch'), the farmer's son sees three swan maidens bathing in water and hides their clothing, in exchange for the youngest of them (sisters, in all) to marry him.[55]

In the Irish fairy tale The Three Daughters of the King of the East and the Son of a King in Erin, three swan maidens come to bathe in a lake (Loch Erne) and converse with a king's elder son, who was fishing at the lake. His evil stepmother convinces a young cowherd to stick a magic pin to the prince's clothes to make him fall asleep. The spell works twice, and in both occasions the swan maidens try to help the prince come to.[56] A similar narrative is the Irish tale The Nine-Legged Steed.[57]

In another Irish tale, The House in the Lake, a man named Enda helps Princess Mave, turned into a swan, to break the curse her evil stepmother cast upon her.[58]

In another tale, goddess Áine, metamorphosed into a swan, was bathing in the lake and was seen by a human duke, Gerald Fitzgerald (Gearóid Iarla) who felt a passionate yearning towards her. Aware of the only way to make her his wife, the duke seized Áine's fairy cloak. Once subdued and deprived of her magic cloak, she resigned to being the human's wife, and they had a son.[59]

In a local legend in the barony of Inchiquin, County Clare, before the O'Briens took the lands of the Clann-Ifearnain, the young chieftain O'Quin follows a stag to the shore of Loch Inchiquin and sees five swans near the water. The five swans take off their swan skins and become maidens. O'Quin steals the garments of one of them; the other turn back into swans and depart, leaving their companion to her fate. The captured swan maiden is wooed by the O'Quin man, until she concedes to marry him, on two conditions: their marriage must be kept a secret and that no man from Clann-Brian must be under their roof, lest she disappears and the man becomes the last of his clan. O'Quin and the swan maiden live seven happy years of marriage, with two children born to them, until a fateful day: O'Quin meets a member of the O'Brien clan and invites him to his castle. He entertains his guest and gambles against him all his worldly goods and possessions, and loses. Remembering his wife's prediction, O'Quin goes to her room and sees her back into swan form, with their two children metamorphosed into cygnets. The swan mother and her children fly away to the mists of the lake, and are seen no more - thus ending the O'Quin line.[60][61] At least 9 accounts of the legend exist: in three of them, the supernatural wife is explicitly a swan maiden.[62] In other accounts, the O'Brien of the legend is identified with Tyge Ahood (or Tadhg an Chomhaid) O'Brien, Prince of Thomond. The number of swans may also vary between tellings: five, seven or a general "number" of them.[63]

Wales

editAuthor Marie Trevelyan stated that the swan appears in Welsh tradition, sometimes "closely connected" to fairies. She also provided the summary of a tale from Whitmore Bay, Barry Island, in Glamorgan that she claimed "was well known in the early part of the nineteenth century". In this story, a young farmer, working in a field near the sea, sees a swan alighting near a stone; the bird takes off its feathers, becomes a woman, bathes for a while, then returns as a bird to the skies. This goes on for some time, until the farmer decides to hide the swan feathers the next time the woman goes to bathe in the lake. It happens thus and the swan woman begs for her feathers back, but the farmer refuses. They eventually marry and he hides the featherskin in a locked oaken chest. One day, the man forgets to lock his chest; the swan woman gets her feathers back and flies away from their home as a swan. The farmer returns home just in time to see her departure, and dies of a broken heart.[64]

In another tale provided by Marie Trevelyan, a man from Rhoose visits his friend in Cadoxton-juxta-Barry, at Barry Island. "Back then" - as this tale goes - , Barry Island was only reachable at low tide. Both friends spend some time together and lose track of time, when the tide has risen high enough to block their return. Both decide to pass by Friar's Point. There, they see two swans alighting and becoming two women by taking off their swan skins. Both men decide to steal the women's skins. Both women beg for the skins and feathers back, but the men deny their request. The swan women marry each men. The wife of the man from Cadoxton is run over by a waggon and, when people come to pick her corpse, she becomes a swan and flies away. As for the other man, after seven years of marriage, the man throws away some rubbish in the farmyard, the swan wings among them. The wife finds them, puts them back and flies away as a swan.[65]

Western Europe

editFlemish fairy tale collections also contain two tales with the presence of the Swan Maiden: De Koning van Zevenbergen ("The King of Sevenmountains")[66] and Het Zwanenmeisje van den glazen Berg ("The Swan Maiden from the Glass Mountain").[67] Johannes Bolte, in a book review of Pol de Mont and Alfons de Cock's publication, noted that their tale was parallel to Grimms' KHM 193, The Drummer.[68]

In an Iberian tale (The Seven Pigeons), a fisherman spots a black-haired girl combing her hair in the rocks. Upon the approach of two pigeons, she finishes her grooming activity and turns into a swan wearing a crown on her head. When the three birds land on a nearby ship, they regain their human forms of maidens.[69]

In a Belgian fairy tale, reminiscent of the legend of the Knight of the Swan, The Swan Maidens and the Silver Knight, seven swans – actually seven princesses cursed into that form – plot to help the imprisoned princess Elsje with the help of the Silver Knight. Princess Elsje, of her own accord, wants to help the seven swan sisters regain her human form by knitting seven coats and staying silent all the while for the enchantment to work.[70]

Germany

editA version of the plot of the Swan Maiden (Schwanenjungfrau) happens in Swabian tale The Three Swans (Von drei Schwänen): a widowed hunter, guided by an old man of the woods, secures the magical garment of the swan-maiden and marries her. Fifteen years pass, and his second wife finds her swan-coat and flies away. The hunter trails after her and reaches a castle, where his wife and her sisters live. The swan-maiden tells him that he must pass through arduous trials in the castle for three nights, to break the curse cast upon the women.[71] The motif of staying overnight in an enchanted castle echoes the tale of The Youth who wanted to learn what Fear was (ATU 326).

In the German tale collected by Johann Wilhelm Wolf (German: Von der schönen Schwanenjungfer; English: The tale of the beautiful swan maiden), a hunter in France sights a swan in a lake who pleads not to shoot her. The swan also reveals she is a princess and, to break her curse, he must suffer dangerous trials in a castle.[72]

In a tale collected in Wimpfen, near the river Neckar (Die drei Schwäne), a youth was resting by the edge of a lake when he sighted three snow-white swans. He fell asleep, and when he woke up, noticed he was transported to a great palace. He then was greeted by three fairy women (implied to be the swans).[73]

Eastern Europe

editCzech author Bozena Nemcova published a tale titled Zlatý vrch ("The Golden Hill"), wherein Libor, a poor youth, lives with his widowed mother in a house in the woods. He finds works under the tutelage of the royal gardener. One day, while resting near a pond, he notices some noise nearby. Spying out of the bushes, he sees three maidens bathing, the youngest the loveliest of them. They don their white robes and "floating veils", become swans and fly away. The next day, Libor hides the veil of the youngest, named Čekanka. The youth convinces her to become his wife and gives her veil for his mother to hide. One day, the swan maiden tricks Libor's mother to return her veil and tells Libor must venture to the Golden Hill if he ever wants her back. With the help of a crow and some stolen magical objects from giants, he reaches the Golden Hill, where Cekanka lives with her sisters and their witch mother. The witch sets three dangerous tasks for Libor, which he accomplishes with his beloved's help. The third is to identify Cekanka in a room with similarly dressed maidens. He succeeds. The pair decides to escape from Golden Hill, as the witch mother goes hot in pursuit. Transforming into different things, they elude their pursuer and return home.[74][75]

Romania

editThe character of the swan-maiden also appears in an etiological tale from Romania about the origin of the swan.[76] In the same book, by professor Moses Gaster, he translated a Romanian "Christmas carol" with the same theme, and noted that the character "occurs very often" in Romania.[77]

Russia

editThe character of the "White Swan" appears in Russian oral poetry and functions similarly to the vila of South Slavic folklore. Scholarship suggests the term may refer to a foreign princess, most likely of Polish origin.[78]

Another occurrence of the motif exists in Russian folktale Sweet Mikáilo Ivánovich the Rover: Mikailo Ivanovich goes hunting and, when he sets his aim on a white swan, it pleads for its life. Then, the swan transforms into a lovely maiden, Princess Márya, whom Mikail falls in love with.[79][80]

In a tale featuring heroic bogatyr Alyosha Popovich, Danilo the Luckless, the titular Danilo the Luckless, a nobleman, meets a "Granny" (an old and wise woman), who points him to the blue ocean. When the water swells, a creature named Chudo-Yudo shall appear, and Danilo must seize it and use it to summon the beautiful Swan Maiden.[81]

In a Kalmyk tale, Tsarkin Khan and the Archer, an Archer steals the robe of a "golden-crowned" swan maiden when she was in human form and marries her. Later, the titular Tsarkin Khan wants to marry the Archer's swan maiden wife and plans to get rid of him by setting dangerous tasks.[82]

Northern Europe

editSweden

editIn a Swedish fairy tale, The Swan-Maiden, the king announces a great hunting contest. A young hunter sights a swan swimming in a lake and aims at it, but the swan pleads not to shoot it. The swan transforms into a maiden and explains she is enchanted into that form, but the hunter may help her to break the spell.[83]

In another Swedish fairy tale collected from Blekinge, The Swan Maiden, a young hunter sees three swans nearing a sound and taking off their animal skins. They reveal themselves to be three lovely maidens and he falls in love with one of them. He returns home and tells his mother he intends to marry one of them. She advises him to hide the maiden's feather garment. He does that the next day and wins a wife for himself. Seven years later, now settled into domestic life, the hunter tells the truth to the swan maiden and returns her feather garment. She changes back into a swan and flies off. The human husband dies a year later.[84][28]

Finnish folklore

editThe usual plot involves a magical bird-maiden that descends from heavens to bathe in a lake. However, there are variants where the maiden and/or her sisters are princesses under a curse, such as in Finnish story Vaino and the Swan Princess.[85]

Asia

editThe swan maiden appears in a tale from the Yao people of China.[86]

In a tale from the Kachari, Sā-se phālāngī gotho-nī khorāng ("The story of the merchant lad"), an orphaned youth decides to earn his living in foreign lands. He buys goods and a boat, and hires some help. He and his crew arrive at another country, where an old couple lived with their pet swan. One day, the youth sees the swan transform into a maiden and becomes enamoured. He buys the swan from the old couple in hopes it will become a girl again, but no such luck. The youth pines away with longing and his mother is worried. A wise woman advises the mother and son to prepare a mixture of ashes and oil, procure a yak's tail and to pretend to fall asleep at night. The swan takes off her animal clothing and, as a human, begins to "worship her country's gods". The youth awakes, takes the plumage and tosses it in the fire. The maiden faints, but the youth uses the mixture on her and fans her with the yak's tail. She awakes and marries the human, giving birth to many children.[87]

America

editA Native American tale has the character of the Red Swan, a bird of reddened plumage. The bird attracts the attention of a young warrior, who goes on a quest to find her.[88]

Literary fairy tales (Kunstmärchen) and other works

editThe Swan maiden story is believed to have been the basis for the ballet Swan Lake, in which a young princess, Odette and her maidens are under the spell of an evil sorcerer, Von Rothbart, transforming them into swans by day. By night, they regain their human forms and can only be rescued if a young man swears eternal love and faithfulness to the Princess. When Prince Siegfried swears his love for Odette, the spell can be broken, but Siegfried is tricked into declaring his love for Von Rothbart's daughter, Odile, disguised by magic as Odette, and all seems lost. But the spell is finally broken when Siegfried and Odette drown themselves in a lake of tears, uniting them in death for all eternity. While the ballet's revival of 1895 depicted the swan-maidens as mortal women cursed to turn into swans, the original libretto of 1877 depicted them as true swan-maidens: fairies who could transform into swans at will.[89] Several animated films based on the ballet, including The Swan Princess and Barbie of Swan Lake depict the lead heroines as being under a spell and both are eventually rescued by their Princes.

The magical swan also appears in Russian poem The Tale of Tsar Saltan (1831), by Alexander Pushkin. The son of the titular Tsar Saltan, Prince Gvidon and his mother are cast in the sea in a barrel and wash ashore in a mystical island. There, the princeling grows up in days and becomes a fine hunter. Prince Gvidon and his mother begin to settle in the island thanks to the help of a magical swan called Princess Swan, and in the end of the tale she transforms into a princess and marries Prince Gvidon.[90]

A variant of the swan maiden narrative is present in the work of Johann Karl August Musäus,[91][92] a predecessor to the Brothers Grimm's endeavor in the early 1800s. The third volume of his Volksmärchen der Deutschen (1784) contains the story of Der geraubte Schleier ("The Stolen Veil").[93] Musäus's tale was translated into English as The Stealing of the Veil, or Tale À La Montgolfier (1791)[94] and into French as Voile envolé, in Contes de Museäus (1826).[95] In a short summary: an old hermit, who lives near a lake of pristine water, rescues a young Swabian soldier; during a calm evening, the hermit reminisces about an episode of his adventurous youth when he met in Greece a swan-maiden, descended from Leda and Zeus themselves – in the setting of the story, the Greco-Roman deities were "genies" and "fairies". The hermit explains the secret of their magical garment and how to trap one of the ladies. History repeats itself as the young soldier sets his sights on a trio of swan maidens who descend from heavens to bathe in the lake.

Swedish writer Helena Nyblom explored the theme of a swan maiden who loses her feathery cloak in Svanhammen (The Swan Suit), published in 1908, in Bland tomtar och troll (Among Gnomes and Trolls), an annual anthology of literary fairy tales and stories.

In a literary work by Adrienne Roucolle, The Kingdom of the Good Fairies, in the chapter The Enchanted Swan, princess Lilian is turned into a swan by evil Fairy Hemlock.[96]

Irish novelist and author Padraic Colum reworked a series of Irish legends in his book The King of Ireland's Son, among them the tale of the swan maiden as a wizard's daughter. In this book, the oldest son of the King of Ireland loses a wager against his father's enemy and should find him in a year and a day's time. He is advised by a talking eagle to spy on three swans that will descend on a lake. They are the daughters of the Enchanter of the Black Back-Lands, the wizard the prince is looking for. The prince is instructed to hide the swanskin of the swan with a green ribbon, who is Fedelma, the Enchanter's youngest daughter.[97]

Male versions

editThe fairytale "The Six Swans" could be considered a male version of the swan maiden, where the swan skin isn't stolen but a curse, similar to The Swan Princess. An evil step-mother cursed her 6 stepsons with swan skin shirts that transform them into swans, which can only be cured by six nettle shirts made by their younger sister. Similar tales of a parent or a step-parent cursing their (step)children are the Irish legend of The Children of Lir, and The Wild Swans, a literary fairy tale by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen.

An inversion of the story (humans turning into swans) can be found in the Dolopathos: a hunter sights a (magical) maiden bathing in a lake and, after a few years, she gives birth to septuplets (six boys and a girl), born with gold chains around their necks. After being expelled by their grandmother, the children bathe in a lake in their swan forms, and return to human form thanks to their magical chains.

Another story of a male swan is Prince Swan (Prinz Schwan), an obscure tale collected by the Brothers Grimm in the very first edition of their Kinder- und Hausmärchen (1812), but removed from subsequent editions.[98]

Czech author Božena Němcová included in the first volume of her collection National Tales and Legends, published in 1845, a tale she titled The Swan (O Labuti), about a prince who's turned into a swan by a witch because his evil stepmother wanted to get rid of him.[99]

Brazilian tale Os três cisnes ("The Three Swans"), collected by Lindolfo Gomes, tells the story of a princess who marries an enchanted prince. After his wife breaks a taboo (he could never see himself in a mirror), he turns into a swan, which prompts his wife on a quest for his whereabouts, with the help of an old woodcutter.[100]

Folklore motif and tale types

editEstablished folkloristics does not formally recognize "Swan Maidens" as a single Aarne-Thompson tale type. Rather, one must speak of tales that exhibit Stith Thompson motif index "D361.1. Swan Maiden",[101] or "B652. Marriage to bird in human form" and other related ones,[102][1] which may be classed AT 400,[14] 313,[103] or 465A.[9] Compounded by the fact that these tale types have "no fewer than ten other motifs" assigned to them, the AT system becomes a cumbersome tool for keeping track of parallels for this motif.[104] Seeking an alternate scheme, one investigator has developed a system of five Swan Maiden paradigms, four of them groupable as a Grimm tale cognate (KHM 193, 92, 93, and 113) and the remainder classed as the "AT 400" paradigm.[104] Thus for a comprehensive list of the most starkly-resembling cognates of Swan Maiden tales, one need only consult Bolte and Polívka's Anmerkungen to Grimm's Tale KHM 193[105] the most important paradigm of the group.[106]

Antiquity and origin

editAncient Indian literature

editIt has been suggested the romance of apsara Urvasi and king Pururavas, of ancient Sanskrit literature, may be one of the oldest forms (or origin) of the Swan-Maiden tale.[107][108][109]

The antiquity of the swan-maiden tale was suggested in the 19th century by Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould, postulating an origin of the motif before the separation of the Proto-Indo-European language, and, due to the presence of the tale in diverse and distant traditions (such as Samoyedic and Native Americans), there was a possibility that the tale may be even older.[110] Another theory was supported by Charles Henry Tawney, in his translation of Somadeva's Kathasaritsagara: he suggests the source of the motif to be old Sanskrit literature; the tale then migrated to Middle East, and from there as an intermediate point, spread to Europe.[111]

Geography and migratory patterns

editA line of scholarship suggests that the dispersal of the swan maiden tale is related to the migratory patterns of swan and similar birds. Jörg Backer contrasts between northern and southern areas where tales appear: swans and cranes in Hungary, Siberia, China, Korea, and Japan; wild geese among the Paleoasian and Eskimo (Inuit) peoples and across Northwestern North America; Peris in form of doves in Iran.[112]

Arthur T. Hatto recognized a mythic look in the character and the narrative, but argued for a location in sub-arctic Eurasia and America, in relation to the migration of swans, cranes, geese and similar waterfowl.[113] Similarly, Edward Allworthy Armstrong recognized the "ancient lineage" of the tale, and supposed an origin in a "northerly climate", north of the Eurasian mountain ranges, where swans are common.[114]

Lotte Motz, in turn, remarked that the story of the swan maiden was "current in the primitive setting of north-Eurasian peoples, where water birds are of importance". That is, she argues, in areas of "archaic economic systems", the swan maiden appears in the folklore of peoples "in which water birds contribute to the economic well-being of the community", which could be affected by the migratory patterns of these birds.[45]

Analysing Yakut tales about a bird maiden, ethnographer S. Ivanovich Nikolaev, in a 1982 article, argued that the motif of the bird maidens taking off their birdskins resembled the act of moulting. According to him, birds losing their wings while also moulting would seem to happen in the Far North, which would indicate the origin of the tale in a Northern location.[115]

E. A. Armstrong also reported that "several" variants of Southern European tradition have the dove-maiden in place of the swan.[116] In this regard, scholarship notes that the common pigeon (rock dove)'s original geographic range seemed restricted to Asia Minor, India, North Africa, and the Southern European countries, like Greece and Italy,[117] while the domesticated dove originated "from North Africa and Near East".[118]

Phylogenetic studies

editEach of them using different methods, i.e. observation of the distribution area of the Swan Maiden type or use of phylogenetic methods to reconstruct the evolution of the tale, Gudmund Hatt, Yuri Berezkin and Julien d'Huy independently showed that this folktale would have appeared during the Paleolithic period, in the Pacific Asia, before spreading in two successive waves in America. In addition, Yuri Berezkin and Julien d'Huy showed that there was no mention of migratory birds in the early versions of this tale (this motif seems to appear very late).[119][120][121]

According to Julien d'Huy, such a motif would also have existed in European prehistory and would have a buffalo maiden as a heroine. Indeed, this author finds the motif with four-legged animals in North America and Europe, in an area coinciding with the area of haplogroup X.[122][123]

Role of the Swan Maiden

editThe swan maiden has been noted to belong to a different race than that of the human husband.[124] According to Alan Miller and Amira El-Zein, the swan maiden is connected both to air (or "sky world") and to water.[125][126] In this regard, in many tales, the swan maiden and her sisters are daughters of a celestial deity, a king of spirits or come from the skies.[127]

The swan maidens embody desirable traits like luck and prosperity.[128] In this regard, according to researcher Serinity Young, she also represents an image of the feminine divine that the male character tries to capture, since she brings prosperity and can lift the latter to "higher states of being, including immortality".[129]

Swan maiden as ancestress

editAccording to scholarship, "an ancient belief in bird-human transformation is manifest in Eurasian mythology".[130] For instance, the mythical character of the swan maiden is found "in the whole of northern Eurasia, from Scandinavia to Manchuria". As such, "a great number of populations" in these regions claim her as their totemic ancestress,[131][132][45] such as the peoples and tribes of Siberia[133] and Central Asia.[134] This narrative is attested in ethnogenetic myths of the Buryat,[135] Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Na-Dené, Bashkir, and Amerindian peoples.[136] Further study suggests that this form of totemic mythology goes back to a pre-Indo-European Nostratic or even Boreal past.[136]

Professor Hazel Wigglesworth, who worked with the many languages of the Philippines archipelago, stated that the character of the mortal male is sometimes named Itung or Beletamey, and he represents a cultural hero or ancestor of the Manobo people.[137][138]

English folklorist Edwin Sidney Hartland mentioned a tale about a divine ancestress of the Bantik people (of the Celebes Island, modern Sulawesi) who comes down to Earth with her seven companions to bathe in a lake. A human male sees them coming to earth and steals the clothing of one of the maidens, thus forcing her to marry him.[139]

19th-century missionary John Batchelor collected an etiological tale from the Ainu people, about the swan maiden. According to this story, the swan - originally created as an angel - is turned into a human woman. She descends to Earth to save an Ainu boy in Takai Sara of the Nikap district. Once he grows up, they marry and father numerous children. She reveals she is a swan, sent to him to "repopulate the Ainu race".[140]

According to scholarship, "in Kazakh and Siberian variants" of the heroic tale of Edige, his mother is described as a Swan Maiden.[132][141] Edige (Edigu) is known as the historical founder of the Nogai Horde.[142]

A line of Russian and Mongolian scholarship suggests that the cult of the swan ancestress developed in the Altai Mountains region (or in Altai-Sayan region),[143] which would explain the common features of the ethnogenetic myths of peoples inhabiting the area, e.g., Turkic and Mongolic peoples.[144] For instance, Buryat professor T. B. Tsydendambaev (ru) supposed that the Mongol-speaking Khorin replaced their canine totem for a swan totem of Turkic origin during the 1st millennium AD.[145]

According to Käthe Uray-Kőhalmi, a trio of celestial sisters, identified as daughters of Heaven itself or of a celestial deity, appear as helpers and wives of male heroes, who marry them and beget clans and dynasties. This motif appears in both the epos and mythologies of the Mongolic and Manchu-Tungus people, where they assume the guise of a water bird, like swans, cranes and wild geese.[146]

Mongolic peoples

editAmong the Buryat, the swan maiden ancestress marries a human man and gives birth to eleven sons,[147] the founders of the future clans of the Khori: Galzuud, Khargana, Khuasai, Khubduud, Baganai, Sharait, Bodonguud, Gushad, Sagan, Khuudai, and Khalbin.[148] In this ancestor myth, the human hunter is called Hori Tumed (Хорь Тумэд); the flock of birds has nine swans, and the swan mother gives names to her 11 sons.[149][150] This is considered to be a "popular genealogical myth", since the protagonist shows variations in his name: Horidai Mergen, Khori, Khorildoi, Khorodoi, Khoreldoi, Khoridoi.[151] The name of legendary swan ancestress of the Khorin is given as Hoboshi (Хобоши).[152]

In one version of an ancestor myth from the Transbaikal Buryats, collected by Jeremiah Curtin in the 19th century, a hunter sees three swans alight near a lake to bathe. They take off their feathers to become young women, daughters of Esege Malan. While they are distracted, the human hunter hides the feathers of one of them, stranding her on Earth. They marry and have six children. One day, she prepares some tarasun for her husband, who, after drinking too much, is convinced by his wife to return her feathers. When she dons them, she once again becomes a swan and returns to the skies, but one of her daughters tries to stop her.[153]

A version of the Khoridai tale with the swan maiden is also attested among the Barga Mongols. The hunter Khoridai marries a swan maiden and she and another wife give birth to 11 ancestors.[151]

The hunter named Hori (and variations) most often appears as the husband of the swan maiden. However, other ethnogenic myths of the Buryats associate him as the swan maiden's son. According to scholarship, four Buryat lines (Khongodor, Horidoy, Khangin, and Sharaid) trace their origins to a marriage between a human hunter and a swan woman named Khurmast-tenger (Хурмаст-тэнгэр), while the Zakamensk Buryats tell the story of three brothers, Hori, Shosholok, and Khongodor, born of a swan maiden.[154]

Among the Khongodor, a genealogical myth tells that the young man Senkhele (Сэнхэлэ) marries the swan maiden (heavenly maiden, in other accounts) Khenkhele-khatan (Хэнхэлэ-хатан) and from their union 9 ancestors are born.[154][155] Similar stories are located among the Khongodor of Tunka, Alar and Zakamen.[156]

A similar myth about a swan ancestress is attested with the Oirats, about a human hunter and his wife, the swan maiden, who represents the heavenly realm (Tengri).[144][131]

In another ethnogenetic myth of the Buryat, the human ancestor is a hunter named Barγutai. One day, he sees seven maidens bathing in a lake and steals the garments of one of them. Six of the maidens wear their garments, become swans and take to the skies again, while the youngest of them is left behind, without her clothing. The hunter finds and consoles her, and they both marry. Eleven children are born of this union. She eventually regains her clothing and returns to the skies.[157]

The swan maiden appears in a tale about the origin of the Daghur people.[86] In this tale, titled The Fairies and the Hunters, a mother lives with her two sons, Kurugure and Karegure. One day, when they are away on a hunt, she is visited by two "female celestials" who take off their feather clothing. Both women help the old mother in her chores and fly away. The old mother tells her sons the story. The next time the celestial women appear, the brothers burn their feather clothing and marry them.[158]

Further scholarship also locates similar tales of the swan ancestress among the Buryat populations. In the Sharayt clan's telling, nine swan maidens fly to Lake Khangai to bathe in the river, and the hunter's name is Sharayhai.[143] In other tellings, the swan maidens number thirteen, and the meeting with the hunter occurs by the river Kalenga, the river Lena,[159] by Lake Baikal, or by Olkhon Island.[160]

Turkic peoples

editScholarship points that, in some Turkic peoples of Northern Asia, the swan appears as their ancestress.[152] One example is Khubai-khatun (Хубай-хатун), who shows up in the Yakut olonkho of Art-toyon. Etymological connections between Khubai-khatun (previously Khubashi) with Mongolic/Buryat Khoboshi have been noted, which would indicate "great antiquity" and possible cultural transmission between peoples.[152]

Scholarship also lists Homay/Humai, the daughter of the King of the Birds, Samrau, in Ural-batyr, the Bashkir epic, as another swan maiden.[161] She appears in folklore as a divine being, daughter of heavenly deity Samrau, and assumes the shape of a bird with solar characteristics.[162]

The swan also appears in an ethnogenetic myth of the Yurmaty tribe as the companion of a human hunter.[163][164]

Swan maiden in shamanism

editAccording to scholarship, "an ancient belief in bird-human transformation is manifest ... in shamanic practices".[130] Edward A. Armstrong and Alan Miller noted that swans appear in Siberian shamanism,[165] which, according to Miller, contains stories about male shamans being born of a human father and a divine wife in bird form.[166][a]

In the same vein, scholar Manabu Waida transcribed a tale collected in Trans-Baikal Mongolia among the Buryat, wherein the human hunter marries one of three swan maidens, daughters of Esege Malan. In another account, the children born of this union become great shaman and shamanesses.[168] A similar story occurs in the Ryukyu Islands, wherein the swan maiden, stranded on Earth, gives birth to a son that becomes a toki and two daughters that become a noro and a yuta.[168]

Researcher Rosanna Budelli also argues for "shamanic reminiscences" in the Arabian Nights tale of Hasan of Basrah (and analogues Mazin of Khorassan and Jansah), for example, the "ornitomorphic costume" of the bird-maidens that appear in the story.[169]

Animal wife motif

editDistribution and variants

editThe motif of the wife of supernatural origin (in most cases, a swan maiden) shows universal appeal, being present in the oral and folkloric traditions of every continent.[170][171] The swan is the typical species, but they can transform into "geese, ducks, spoonbills, or aquatic birds of some other species".[31] Other animals include "peahens, hornbills, wild chickens, parakeets and cassowaries".[172]

ATU 402 ("The Animal Bride") group of folktales are found across the world, though the animals vary.[173] The Italian fairy tale "The Dove Girl" features a dove. There are the Orcadian and Shetland selkies, that alternate between seal and human shape. A Croatian tale features a she-wolf.[174] The wolf also appears in the folklore of Estonia and Finland as the "animal bride", under the tale type ATU 409, "The Girl as Wolf".[175][176]

In Africa, the same motif is shown through buffalo maidens.[177][178][b] In addition, according to American folklorist William Bascom, in similar narratives among the Yoruba and the Fon the animal wife is an African buffalo, a gazelle, a hind, sometimes a duiker or antelope.[181][182]

In East Asia, it is also known featuring maidens who transform into various bird species.

Russian professor Valdemar Bogoras collected a tale from a Yukaghir woman in Kolyma, in which three Tungus sisters change into "female geese" to pick berries. On one occasion, the character of "One-Side" hides the skin of the youngest, who cannot return to goose form. She eventually consents to marry "One-Side".[183]

In a tale attributed to the Toraja people of Indonesia, a woman gives birth to seven crabs that she throws in the water. As time passes, the seven crabs find a place to live and take their disguises to assume human form. In one occasion, seven males steal the crab disguises of the seven crab maidens and marry them.[184] A second one is close to the Swan maiden narrative, only with parakeets instead of swans; the hero is called Magoenggoelota and the maiden Kapapitoe.[185]

In mythology

editOne notably similar Japanese story, "The crane wife" (Tsuru Nyobo), is about a man who marries a woman who is in fact a crane (Tsuru no Ongaeshi) disguised as a human. To make money the crane-woman plucks her own feathers to weave silk brocade which the man sells, but she became increasingly ill as she does so. When the man discovers his wife's true identity and the nature of her illness, she leaves him. There are also a number of Japanese stories about men who married kitsune, or fox spirits in human form (as women in these cases), though in these tales the wife's true identity is a secret even from her husband. She stays willingly until her husband discovers the truth, at which point she must abandon him.[186]

The motif of the swan maiden or swan wife also appears in Southeast Asia, with the tales of Kinnari or Kinnaree (of Thailand) and the love story of Manohara and Prince Sudhana.[187]

Professor and folklorist James George Frazer, in his translation of The Libraries, by Pseudo-Apollodorus, suggested that the myth of Peleus and Thetis seemed related to the swan maiden cycle of stories.[188]

In folklore

editEurope

editIn a 13th-century romance about Friedrich von Schwaben (English: "Friedrich of Suabia"),[189] the knight Friedrich hides the clothing of Princess Angelburge, who came to bathe in a lake in dove form.[190][191]

Western Europe

editIn a tale from Brittany, collected by François-Marie Luzel with the title Pipi Menou et Les Femmes Volants ("Pipi Menou and the Flying Women"), Pipi Menou, a shepherd boy, sees three large white birds descending near a étang (a pond). When the birds approach the pond, they transform into nude maidens and begins to play in the water. Pipi Menou sees the whole scene from the hilltop and tells his mother, who explains they are the daughters of a powerful magician who lives elsewhere, in a castle filled with jewels and precious stones. The next day, he steals the clothing of one of them, but she convinces him to give it back. He goes to the castle, the flying maiden recognizes him and they both escape with jewels in their pouches.[192]

Southern Europe

editPortuguese writer Theophilo Braga collected a Portuguese tale named O Príncipe que foi correr a sua Ventura ("The Prince Who Wanted to See the World"), in which a prince loses his bet against a stranger, a king in disguise, and must become the stranger's servant. The prince is informed by a beggar woman with child that in a garden there is tank, where three doves come to bathe. He should take the feathery robe of the last one and withhold it until the maiden gives him three objects.[193]

A tale from Tirol tells of prince Eligio and the Dove-Maidens, which bathe in a lake.[194]

In another tale, from Tirol, collected by Christian Schneller (German: Die drei Tauben; Italian: Le tre colombe; English: "The Three Doves"), a youth loses his soul in a gamble to a wizard. A saint helps him and gives the information about three doves that perch themselves on a bridge and change themselves to human form. The youth steals the clothing of the youngest, daughter of the wizard, and promises to take him to her father. She wants to help the hero in order to convert herself to Christianity and abandon her pagan magic.[195]

Spain

editIn a Basque tale collected by Wentworth Webster (The Lady Pigeon and her Comb), the destitute hero is instructed by a "Tartaro" to collect the pigeon garment of the middle maiden, instead of the youngest.[196]

In the Andalusian variant, El Marqués del Sol ("The Marquis of the Sun"), a player loses his bet against the Marqués and must wear out seven pairs or iron shoes. In his wanderings, he pays the debt of a dead man and his soul, in gratitude, informs him that three white doves, the daughters of the Marqués in avian form, will come to bathe in a lake.[197]

In a variant collected by folklorist Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Sr. in Granada, a gambling prince loses a bet against a dove (the Devil, in disguise), who says he should find him in "Castillo de Siete Rayos de Sol" ("The Castle of Seven Sunrays"). A helping hermit guides him to a place where the three devil's daughters, in the form of doves, come to bathe. The prince should steal the garments of the youngest, named Siete Rayos de Sol, who betrays her father and helps the human prince.[198]

In an Asturian tale collected by Aurelio del Llano, the youngest of three brothers works with a giant, who forbids him to open a certain door. He does and sees three dove maidens alighting near the water, becoming woman and bathing. The youth tells the giant about this event, and his employer suggests he steals the feather of the one he set his sights on. He takes the feather of one of the dove maidens, marries her and gives her feather to his mother to keep. Hispanist Ralph Steele Boggs classified it as type 400*B (a number not added to the revision of the international index, at the time).[199]

Northern Europe

editIn the Danish tale The White Dove, the youngest prince, unborn at the time, is "sold" by his elder brothers in exchange for a witch's help in dissipating a sea storm. Years later, the witch upholds her end of the bargain and takes the prince under her tutelage. As part of his everyday chores, the witch sets him with difficult tasks, which he accomplishes with the help of a princess, enchanted by the witch to become a dove.[200][201]

Central Europe

editA compilation of Central European (Austrian and Bohemian) folktales lists four variants of the Swan Maiden narrative: "The Three White Doves";[202] "The Maiden on the Crystal Mountain";[203] "How Hans finds his Wife",[204] and "The Drummer".[205] Theodor Vernaleken, in the German version of the compilation, narrated in his notes two other variants, one from St. Pölten and other from Moldautein (modern day Týn nad Vltavou, in the Czech Republic).[206]

Eastern Europe

editIn Slavic fairy tale King Kojata or Prince Unexpected, the twelve royal daughters of King Kostei take off their geese disguises to bathe in the lake, but the prince hides the clothing of the youngest.[207][208]

In Czech tale The Three Doves, the hero hides the three golden feathers of the dove maiden to keep her in her human state. Later on, when she disappears, he embarks on an epic quest to find her.[209]

In a Serbian tale collected by Vuk Karadzic and translated as Die Prinz und die drei Schwäne ("The Prince and the Three Swans"), a prince loses his way during a hunt and meets an old man who lives in a hut. He works for the old man, and has to watch over a lake. On the second day of his job, three swans alight near the lake, take off their birdskins to become human maidens and bathe. The next day, the prince steals their swan skins and hurries back to the old man's hut. The three swans beg for their birdskins back; the old man returns only two of them and withholds the youngest's skin. He marries the prince to the swan girl and they return to his father's kingdom. Once there, one day, the swan wife asks her mother-in-law for her garments back; she puts it on and flies away to the Glass Mountain. The prince goes back to the old man, who is the king of the winds, and is directed to the Glass Mountain. The climbs it and meets an old woman in a hut. Inside the hut, he must identify his wife from a group of 300 similarly dressed swan women. Later, he is forced to do chores for the old woman, which he does with his wife's help.[210]

Russia

editIn the Russian fairy tale The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise, or Vassilissa the Cunning, and The Tsar of the Sea,[211] Ivan, the merchant's son, was informed by an old hag (possibly Baba Yaga, in some versions[212]) about the daughters of the Sea Tsar who come to bathe in a lake in the form of doves. In another translation, The King of the Sea and Melania, the Clever,[213] and The Water King and Vasilissa the Wise,[214] there are twelve maidens in the form of spoonbills. In another transcription of the same tale, the maidens are pigeons.[215]

In another Russian variant, "Мужик и Настасья Адовна" ("The Man and Nastasya Adovna"), collected by Ivan Khudyakov, a creature jumps out of a well and tells a man to give him the thing he does not know he has at home (his newly born son). Years later, his son learns about his father's dealing and decides to travel to "Hell" ("Аду" or "Adu", in Russian). He visits three old women who give him directions to reach "Hell". The third old woman also informs him that in a lake, thirty-three maidens, the daughters of "Adu", come to bathe, and he should steal the clothing of Nastasya Adovna.[216]

In a tale from Perm Krai with the title "Иванушка и его невеста" ("Ivanushka and his Wife"), Ivanushka loses his way from his grandfather in the forest, but eventually finds a hut. He takes shelter with an old man for the night, and, the next day, the old man gives directions, but Ivanushka disregards them and finds a lake where maidens are bathing. The maidens leave the water, turn into ducks and depart. Ivanushka goes back the old man and he advises him to steal the duck maiden's garments. Ivanushka does that and takes the girl for wife. She eventually retrieves her duck garments, bids Ivanushka to find her in a land beyond 30 realms, then flies away.[217]

Ukraine

editIn a "Cossack" (Ukrainian) tale, The Story of Ivan and the Daughter of the Sun, the peasant Ivan obtains a wife in the form of a dove maiden whose robe he stole when she was bathing. Some time later, a nobleman lusts after Ivan's dove maiden wife and plans to get rid of the peasant.[218]

In another Ukrainian variant that begins as tale type ATU 402, "The Animal Bride", akin to Russian The Frog Princess, the human prince marries the frog maiden Maria and both are invited to the tsar's grand ball. Maria takes off her frog skin and enters the ballroom as human, while her husband hurries back home and burns her frog skin. When she comes home, she reveals the prince her cursed state would soon be over, says he needs to find Baba Yaga in a remote kingdom, and vanishes from sight in the form of a cuckoo. He meets Baba Yaga and she points to a lake where 30 swans will alight, his wife among them. He hides Maria's feather garment, they meet again and Maria tells him to follow her into the undersea kingdom to meet her father, the Sea Tsar. The tale ends like tale type ATU 313, with the three tasks.[219]

Hungary

editA Hungarian tale ("Fisher Joe") tells about an orphan who catches a magical fish that reveals itself as a lovely maiden.[220] A second Magyar tale, "Fairy Elizabeth", is close to the general swan maiden story, only dealing with pigeon-maidens instead.[221] In a third tale, Az örökbefogadott testvérek ("The adoptive brothers"), the main protagonist, Miklós, dreams that the Queen of the Fairies and her handmaidens come to his side in the form of swans and transform into beautiful women.[222]

In the Hungarian tale Ráró Rózsa, the king promises his only son to a devil-like character that rescues him from danger. Eighteen years pass, and it is time for the prince to fulfill his father's promise. The youth bides his time in a stream and awaits the arrival of three black cranes, the devil's three daughters in disguise, to fetch the garments of the youngest.[223]

In another tale, Tündér Ilona és Argyilus ("Fairy Ilona and Argyilus"), Prince Argyilus (hu) is tasked by his father, the king, with discovering what has been stealing the precious apples from his prized apple tree. One night, the prince sees thirteen black ravens flying to the tree. As soon as he captures the thirteenth one, it transforms into the beautiful golden-haired Fairy Ilona.[224] A variant of the event also happens in Tündér Ilona és a királyfi ("Fairy Ilona and the Prince").[225]

In the tale A zöldszakállú király ("The Green-Bearded King"), the king is forced to surrender his son to the devil king after it spares the man's life. Years later, the prince comes across a lake where seven wild ducks with golden plumage left their skins on the shores to bathe in the form of maidens.[226]

In the tale A tizenhárom hattyú ("The Thirteen Swans"), collected by Hungarian journalist Elek Benedek, after his sister was kidnapped, Miklós finds work as a cowherd. On one occasion, when he leads the cows to graze, he sees thirteen swans flying about an apple tree. The swans, then, change their shapes into twelve beautiful maidens and the Queen of the Fairies.[227]

Albania

editIn an Albanian-Romani tale, O Zylkanôni thai e Lačí Devlék'i ("The Satellite and the Maiden of Heaven"), an unmarried youth goes on a journey to find work. Some time later, he enters a dark world. There, he meets by the spring three partridges that take off their animal skins to bathe. The youth hides the garment of one of them, who begs him to give it back. She wears it again and asks him to find her where the sun rises in that dark world.[228]

Caucasus Region

editIn an Azerbaijani variant, a prince travels to an island where birds of cooper, silver and gold wings bathe, and marries the golden-winged maiden.[229]

In an Armenian variant collected from an Armenian-American source (The Country of the Beautiful Gardens), a prince, after his father's death, decided to stay silent. A neighbouring king, who wants to marry him to his daughter, places him in his garden. There, he sees three colorful birds bathing in a pool, and they reveal themselves as beautiful maidens.[230]

Latvia

editAccording to the Latvian Folktale Catalogue, tale type ATU 400 is titled Vīrs meklē zudušo sievu ("Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife"). In the Latvian tale type, the protagonist finds the bird maidens (swans, ducks, doves) alighting near a lake to bathe, and steals the youngest's wings.[231]

In a Latvian folktale, a female named Laima (possibly the Latvian goddess of fate) loses her feathered wings by burning. She no longer becomes a swan and marries a human prince. They live together in the human world and even have a child, but she wants to become a swan again. So her husband throws feathers at her, she regains her bird form and takes to the skies, visiting her mortal family from time to time.[232]

Lithuania

editIn another Lithuanian variant published by Fr. Richter in the journal Zeitschrift für Volkskunde with the title Die Schwanfrau ("The Swan Woman"), a count's son, on a hunt, sights three swans, who talk among themselves that whoever is listening to them may help them break their curse. The count's son comes out of a bush and agrees to help them: by fighting a giant and breaking the spell a magician cast on them.[233]

Northern Eurasia

editIn a tale from the Samoyed people of Northern Eurasia, an old woman informs a youth of seven maidens who are bathing in a lake in a dark forest.[234] English folklorist Edwin Sidney Hartland cited a variant where the seven maidens arrive at the lake in their reindeer chariot.[16] Whatever their origin, scientist Fridtjof Nansen reported that, in these tales, the girls lived "in the air or in the sky".[235]

Philosopher John Fiske cited a Siberian tale wherein a Samoyed man steals the feather skin of one of seven swan maidens. In return, he wants her help in enacting his revenge on seven robbers who killed his mother.[236] In another version of this tale, still sourced from the Samoyed and translated by Charles Fillingham Coxwell, the seven man have kidnapped the sister from a Samoyed man, and the protagonist steals the garments of a woman from the sky to ensure her help.[237]

In a tale attributed to the Tungus of Siberia, titled Ivan the Mare's Son (Russian: "Иван Кобыльников сын")[238][239] - related to both Fehérlófia and Jean de l'Ours -, a mare gives birth to a human son, Ivan. When he grows up, he meets two companions also named Ivan: Ivan the Sun's Son and Ivan the Moon's Son. The three decide to live together in a hut made of wooden poles and animal skins. For two nights, after they hunt in the forest, they come home and see the place in perfect order. On the third night, Ivan, the Mare's Son, decides to stay awake and discovers that three herons descending to the ground and taking off their feathers and wings to become maidens. Ivan, the Mare's Son, hides their bird garments until they reveal themselves. Marfida, the heron maiden, and her sisters marry the three Ivans and the three couples live together. The rest of the story follows tale type ATU 301, "The Three Stolen Princesses": descent into underworld by hero, rescue of maidens, betrayal by companions and return to the upper world on eagle.[240]

In a Mongolian tale, Manihuar (Манихуар), a prince on a hunt sees three swans take off their golden crowns and become women. As they bathe in a nearby lake, he takes the golden crown of one of them, so she can't turn back into her bird form. He marries this swan maiden, named Manihuar. When the prince is away, his other wives threaten her, and Manihuar, fearing for her life, convinces her mother-in-law to return her golden crown. She turns back into a swan and flies back to her celestial realm. Her husband goes on a quest to bring her back.[149]

Scholar Kira van Deusen collected a tale from an old Ul'chi storyteller named Anna Alexeevna Kavda (Grandma Nyura). In her tale, titled The Swan Girls, two orphan brothers live together. The older, Natalka, hunts game for them, while the youngest stays at home. One day, seven swans (kilaa in the Ulch language) land near their house and turn into seven human women. They enter the brothers' house, do the chores, sew clothes for the younger sibling and leave. He tells Natalka the story and they decide to capture two of the maidens as spouses for them.[241]

Yakut people

editIn an olonkho (epic narrative of the Yakut or Sakha people) titled Yuchyugey Yudyugyuyen, Kusagan Hodzhugur, obtained from Olonhohut ('storyteller', 'narrator') Darya Tomskaya-Chayka, from Verkhoyansk, Yuchugey Yudyugyuyen, the elder of two brothers, goes hunting in the taiga. Suddenly, he sees 7 Siberian cranes coming to play with his young brother Kusagan Hodzhugur, distracting him from his chores. The maidens possibly belong to the Aiy people, good spirits of the Upper World in Yakut mythology.[242] When they come a third time, the elder brother, Yuchugey, disguises himself as a woodchip or a flea and hides the bird skin of one of the crane maidens. They marry. One day, she fools her brother-in-law, regains her magical crane garment and returns to the Upper World. Hero Yuchugey embarks on a quest to find her, receiving help from a wise old man. Eventually, he reaches the Upper world and finds his wife and a son in a yurt. Yuchugey burns his wife's feathers; she dies, but is revived, and they return to the world of humans.[243][244][245] This narrative sequence was recognized as very similar to a folk tale.[244][245]

Russian ethnographer Ivan Khudyakov collected a Yakut tale titled "Хороший Юджиян", published in 1890. Its plot is very similar to the olonkho: two brothers live together, one hunts and the other stays home. The one who stays home is visited by seven Siberia cranes who change shape into maidens, clean their house, and depart as cranes. The first brother captures and marries one them by hiding her crane skin, and they have a child. One day, the second brother gives back the plumage to his sister-in-law, the maiden becomes a crane again and flies away. The first brother jumps on his horse and follows his wife to her celestial realm. Once there, he is advised to creep into her hut and play with his child on their cradle to draw the mother's attention. The crane maiden enters the hut to rock her baby, and her husband appears.[246]

Variants of the Yakut tale "Үчүгэй Үɵдүйээн" (Russian: "Хороший Юджиян") were collected in the northern part of the Republic of Sakha and show great resemblance between them.[247] According to Russian scholarship, Yakut professor Dmitry Kononovich (D. K.) Sivtsev-Suorun Omolloon based himself on the international classification put forth by Antti Aarne in 1910 and later expanded by other folklorists, and classified these Yakut narratives as type 400C, "Муж возвращает убежавшую жену" ("Man goes after his runaway wife"): the bird maiden (a stork or Siberian crane maiden) wears its featherskin and escapes; man goes after her in the sky; she dies, but he resurrects her.[248]

West Asia

editThe tale of the swan maiden also appears in the Arab collection of folktales The Arabian Nights,[249] in "The Story of Janshah",[250] a tale inserted in the narrative of The Queen of the Serpents. In a second tale, the story of Hasan of Basrah (Hassan of Bassorah),[251][252] the titular character arrives at an oasis and sees the bird maidens (birds of paradise) undressing their plumages to play in the water.[253] Both tales are considered to contain the international tale of the Swan Maiden.[254]

In another Middle Eastern tale, a king's son finds work with a giant in another region and receives a set of keys to the giant's abode, being told not to open a specific door. He disobeys his master and opens the door; he soon sees three pigeon maidens take off their garments to bathe in a basin.[255]

In a Metawileh tale reported in the Palestine Exploration Quarterly, Shâtir Hassan, son of a merchant, pursues a bird-girl named Bedr et Temâm, daughter of the King of the Jân. The report described the tale as a version of the "Swan maiden" tale.[256]

South Asia

editA story from South Asia also narrates the motif of the swan maiden or bird-princess: Story of Prince Bairâm and the Fairy Bride, when the titular prince hides the clothing of Ghûlab Bânu, the dove-maiden.[257][258]

Central Asia

editIn a Tuvan tale, Ösküs-ool and the Daughter of Kurbustu-Khan, poor orphan boy Ösküs-ool seeks employment with powerful khans. He is tasked with harvesting their fields before the sun sets, of before the moon sets. Nearly finishing both chores, the boy pleads to the moon and the sun to not set for a little longer, but time passes. The respective khans think they never finished the job, berate and whip him. Some time later, while living on his own, the daughter of Khurbustu-khan comes from the upper world in the form of a swan. The boy hides her clothing and she marries him, now that she is stranded on Earth. Some time later, an evil Karaty-khan demands that the youth produces a palace of glass and an invincible army of iron men for him - feats that he accomplishes thanks to his wife's advice and with help from his wife's relatives.[259]

East Asia

editAccording to professor Alan Miller, the swan maiden tale is "one of the most popular of all Japanese folktales".[166] Likewise, scholar Manabu Waida asserted the popularity of the tale "in Korea, Manchuria and China", as well as among "the Buryat, Ainu and Annamese".[168]

China

editIn ancient Chinese literature, one story from the Dunhuang manuscripts veers close to the general Swan Maiden tale: a poor man named T'ien K'un-lun approaches a lake where three crane maidens are bathing.[260][261]

A tale from Southeastern China and near regions narrates the adventures of a prince who meets a Peacock Maiden, in a tale attributed to the Tai people.[262][263] The tale is celebrated amongst the Dai people of China and was recorded as a poem and folk story, being known under several names, such as "Shaoshutun", "The Peacock Princess" or "Zhao Shutun and Lanwuluona".[264][265][266]

In a Chuan Miao tale, An Orphan Enjoyed Happiness and His Father-in-law Deceived Him, but His Sons Recovered Their Mother, an orphan gathers wood in the forest and burns the dead trees to make way for a clearing. He also builds a well. One day, seven wild ducks light on the water. The orphan asks someone named "Ye Seo" about the ducks, who answers the youth they are his fortune and that he must secure a "spotted feather" from their wings. The next day, the youth hides near the well when the ducks arrive and plucks the spotted feather, which belongs to an old woman. He goes back to Ye Seo, who tells him he needs to get a white feather, not a spotted one, nor a black one. He fetches the correct feather this time and a young woman appears to become his wife. They marry and she gives birth to twin boys. For some time, both children cry every time their mother is at home, until one day she asks them the reason for their sadness. They explain that their human father is hiding their mother's feather somewhere in the house and wears it on his head when she is not at home. She finds the feather, puts it on her head and flies away from home. The boys' human father scolds them and sends them to seek their mother.[267]

In a Chinese tale titled The Seven Snow-White Cranes, a scholar is walking somewhere on a bright day, when seven cranes being to fly down to the ground near him. The man hides behind some bushes and sees the cranes alighting near a pond, then taking off their feather garments to become human maidens. As they play and frolic in the water, the scholar steals the garments of one of the crane maidens, who pick up their featherskins, turn back into cranes and fly away, save for one of them. The scholar appears to her and brings her home to be his wife. They have a son the next year, but the maiden still longs for the skies. One day, a maidservant takes all clothes inside the house and places them in the sun, along them the crane garments, which were hidden in a camphor chest. The crane maiden finds her garments and, with great joy, turns back into a crane and goes back to the heavens. Years pass, and their son grows up being mocked for not having a mother. He asks his scholar father where he can see his mother, and the man tells him to go to a certain hill and shout for a passing flock of seven cranes. The boy does as instructed and the crane maiden meets her son in human form. The boy asks for her to come back, which she cannot do, but, in return, gives him a magic gourd.[268]

Africa

editAccording to scholar Denise Paulme, in African tales, the animal spouse (a buffalo or an antelope) marries a human male already married to a previous human wife. The man hides the skin of the supernatural spouse and she asks him never to reveal her true name. When the husband betrays the supernatural wife's trust, the animal wife takes her skin back and returns to the wilderness with her children.[269]

Variants collected in Cape Verde by Elsie Clews Parsons (under the title White-Flower) show the hero plucking the feather from the duck maiden to travel to her father's house.[270]

In a Kabylian tale collected by ethnologist Leo Frobenius with the title Die Taubenfrauen ("The Dove Maidens"): a young hunter journeys and meets two women who invite him to live with them as their brother. One day, two doves land near their house and become maidens. They turn the man to stone, turn back to doves and fly away. The next time they land, the hunter's adopted sisters hide the dove garments and golden jewellery of one of the dove maidens, in return for changing their brother back. The dove maiden does. The sisters give the garments to the hunter. The dove maiden marries the hunter and bears him a son. Some time later, he wants to visit his mother in his home village. He takes his dove wife and son. The hunter gives his mother the dove wife's belongings and explains she must never let her leave the house and to hide the garments and jewellery. One day, the dove maiden goes out for a bit and a harvester becomes entranced by her beauty. The man tells the dove wife she must marry him. The dove wife begs her mother-in-law to give her belongings so she may escape. After getting the garments, she turns into a dove, takes her son and flies over to the village of Wuak-Wuak. The hunter returns home and goes after her. He fools three people fighting over magical objects, steals them and teleports to Wuak-Wuak. There, he finds his wife and son, but his dove wife explains the whole village only has females and if they see him, her sisters will devour him.[271]