This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Swedish War of Liberation (1521–1523; Swedish: Befrielsekriget, lit. 'The Liberation War'), also known as Gustav Vasa's Rebellion and the Swedish War of Secession, was a significant historical event in Sweden. Gustav Vasa, a nobleman, led a rebellion and civil war against King Christian II. The war resulted in the deposition of King Christian II from the throne of Sweden, effectively ending the Kalmar Union that had united Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. This conflict played a crucial role in shaping Sweden's national identity and history.

| Swedish War of Liberation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Dano-Swedish wars | |||||||||

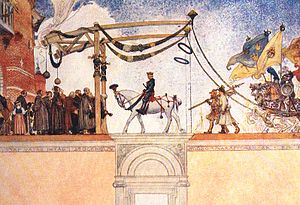

The Entry of Gustav Vasa into Stockholm Carl Larsson, oil on canvas, 1908 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 12,000 | 27,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Less than 4,000 | About 10,000 | ||||||||

Johan Gustaf Sandberg, oil on canvas, 1836.

Background

editKing Christian II, along with his ally, Swedish Archbishop Gustav Trolle, attempted to suppress the separatist Sture party within the Swedish nobility by executing numerous members during the Stockholm Bloodbath. The King faced discontent due to his imposition of high taxes on the peasantry. Furthermore, the presence of German and Danish nobles and commoners in most Swedish castles further fueled the anger of native Swedish nobility.

Economics

editIn the background was an economic power struggle over the mining and metal industry in Bergslagen,[1] Sweden's main mining region in the 16th century. This struggle significantly increased the financial resources available to the military, while also exacerbating existing conflicts over the Kalmar Union. The key players in this economic competition were:

- Jakob Fugger, an early and immensely wealthy industrialist in the mining and metal industries on the continent, who sought to execute a hostile business takeover of Bergslagen. He formed alliances with Pope Leo X and the Swedish Archbishop Gustav Trolle, both of whom depended on him economically, as well as with the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I and Christian II of Denmark/Norway, who asserted his claim to the throne of the Union, including Sweden. His marriage to Isabella of Austria in 1515 strengthened this alliance.

- The Hanseatic League, represented by the Free City of Lübeck, which had a virtual monopoly on trade with Sweden and Bergslagen. The League was allied with the Swedish regents Sten Sture the Younger and later Gustav Vasa, creating a strong dependence on the League.

Christian II's planned invasion of Sweden, coupled with Fugger's intended takeover of the industry in Bergslagen, was financed both by the substantial dowry of Christian II's wife and by Fugger himself. However, Fugger withdrew from the battle in 1521 after being defeated by Gustav Vasa at the Battle of Västerås, relinquishing control of shipping from Bergslagen. As a result, Christian II lost both the resources needed to win the war against Gustav Vasa and the means to maintain his position in Denmark against his uncle, Frederick I of Denmark, by 1523.

The significant increase in funding and financial dependence allowed the parties to at times afford larger numbers of expensive hired mercenaries, leading to fluctuations in power and abrupt shifts in the dynamics of the war. The costs were considerable, and after Christian III's victory alongside Gustav Vasa's Sweden in the Count's Feud in Skåne and Denmark, the funds were exhausted by 1536, marking the end of the influence of the Catholic Church and the Hanseatic League in the Nordic countries.

Rebellion 1521

editThe war began in January 1521, when Gustav Vasa was appointed hövitsman (commander) over Dalarna by representatives of the people in the northern part of the province. After Gustav Vasa captured the copper mine at Stora Kopparberget and the town of Västerås, more men joined his army. In 1522, the Hanseatic city of Lübeck formed an alliance with the Swedish rebels. After the capture of Stockholm in June 1523, the rebels effectively ruled Sweden, and on 6 June, Gustav Vasa was elected King of Sweden in the town of Strängnäs. By September, Gustav Vasa's supporters also controlled Swedish Finland. The Treaty of Malmö, signed on 1 September 1524, formalized Sweden's secession from the Kalmar Union.

Initially, Gustav's role in the war against Christian II was as one of several rebel leaders, each active in different parts of the country. The war that eventually led to his coronation was only partially instigated and led by him. The term "Gustav Vasa's War of Liberation", often used in historiography, derives primarily from the war's outcome—Gustav Vasa's ascension to the throne of an independent Sweden—rather than its initial impetus and course. Contemporary research also indicates that Gustav himself did not directly oversee any military operations, delegating such responsibilities to associates with greater military experience.[2]

Dalarna

editThe details of Gustav Vasa's activities in Dalarna in 1520 remain largely unknown due to the scarcity of sources. The most comprehensive account available was written during Gustav's reign by his close associate, Bishop Peder Andreæ Swart of Västerås, which some historians speculate was heavily influenced by Gustav himself.[3]

In 1520, Gustav Vasa traveled to the Swedish province of Dalarna, disguised as a peasant to avoid detection by King Christian's scouts. Arriving in the city of Mora in December, he sought the peasants' help in his uprising against Christian II. When he was rebuffed, Gustav Vasa decided to travel north in search of supporters for his cause. A couple of refugees arrived in Mora and told of the atrocities committed by Christian II and his troops. Moved by these accounts, the people of Mora decided to locate Gustav Vasa and join his rebellion, sending two skilled skiers for the task. They eventually intercepted him in Sälen. (The Vasaloppet, a 90 km (56 mi) ski race, commemorates this remarkable escape from Christian II's soldiers in the winter of 1520–1521, but follows the reverse route from Sälen back to Mora. Legend has it that he fled on skis).[4][5]

Upon his return to Mora, on New Year's Eve 1521, Gustav Vasa was appointed hövitsman by emissaries from all the parishes of northern Dalarna.

In March, Gustav Vasa left Mora with about 100 men and plundered Kopparberg. Soon after, the peasants of Bergslagen rallied to the cause, swelling Gustav Vasa's forces to over 1,000 men.

Battle of Brunnbäck Ferry

editWhen news of the Swedish uprising reached Christian II, he sent a contingent of Landknechten to put down the rebellion. In April 1521, the Union forces clashed with Gustav Vasa's followers at Brunnbäck Ferry, resulting in the decisive defeat of the king's army. This triumph greatly boosted the morale of the Swedish rebels.

An emergency mint was set up in Dalarna to produce the copper coins needed to finance the war effort.

Battle of Västerås

editThe rebel army advanced south to Västerås, which they captured and plundered in the Battle of Västerås 29 April 1521. Upon hearing of Gustav Vasa's triumph, supporters of the Sture family decided to join the rebellion. Västerås marked a pivotal moment in Gustav Vasa's fortunes, as the rebels gained control of the shipping routes from Bergslagen and Fugger stopped funding Christian II.

In April, Gustav Trolle had been sent to Hälsingland, but when his two hundred cavalry encountered the thousand strong peasant army, they fled south. By the end of April 1521, Gustav Vasa had secured supremacy in Dalarna, with support from Gästrikland, Västmanland, and Närke, but without the fortresses.

On July 15, 1521, the Riksdag met in Stockholm and offered Gustav Vasa a free lease on Stockholm with forgiveness for all transgressions. As a gesture of goodwill, Gustav Trolle had Didrik Slagheck imprisoned, and was promised substantial supplies of malt and hops. Gustav Vasa hesitated and waited for developments. The rebellion soon reached Brunkeberg, although the peasants found it impossible to besiege the town.

The summer of 1521 brought relative peace. Many returned to their farms to help with the harvest.

After Västerås – Professional armies

editThe importance of peasant armies diminished in the conflict, and the war was fought primarily by German mercenaries and recruited Swedish soldiers, supplemented by cavalry from the Swedish nobility.[6]

1521 – Gustav Vasa becomes head of state

editLars Siggesson Sparre, who had previously been a hostage of Christian II but had defected to the king's side, now sided with Gustav Vasa. Hans Brask and Ture Jönsson Tre Rosor also switched allegiance to Gustav Vasa, and in the second half of August he was recognized as the leader of Sweden by the provinces of Gotland at a meeting in Vadstena. At the same time, the government appointed by Christian II withdrew from Swedish territory.

The assembly in Vadstena in 1521, which declared Gustav as head of state, consisted of a relatively small group of prominent individuals, mainly from the southern provinces. The peasants and other supporters who had propelled him forward in the earlier stages of the uprising were not represented. In addition, most of the nobility in Östergötland, Sörmland, and Uppland remained loyal to King Christian of the Union. However, the continued expansion of the rebellion and the election of the nobleman Gustav as head of state caused many to switch sides or flee to Denmark to avoid reprisals.

1522 – The Hansa joins

editJust before Christmas in 1521, Berend von Melen, the commander of Stegeborg in Östergötland, transferred control to Gustav Eriksson, resulting in the castle's capture by the rebel army. With Berend's help, Gustav gained a valuable ally with considerable military experience and strong connections to the Hanseatic League in Lübeck.

The castles of Örebro and Västerås were besieged and taken in early 1522. However, the most important fortresses remained strong. Gustav and his allies realized that these fortresses could not be taken without warships and heavy artillery.

Negotiations began with Lübeck, which had its own interest in unimpeded trade, free from the restrictions imposed by the Danish king. In exchange for aid in the form of ships, soldiers, cannons and other essential supplies, Lübeck was promised exemption from customs duties in Sweden. From May, Lübeck took an active part in the conflict, and in the fall it intensified the siege of the Danish strongholds of Stockholm and Kalmar. At the same time, Gustav, Berend von Melen, and Lübeck strategized an operation to conquer Skåne and other regions in eastern Denmark. A naval battle near Stockholm cut off vital supplies to the Danish garrison stationed there.

1523 – Gustav Vasa becomes king

editThe campaign against Skåne was planned for January 1523, but was not carried out. Instead, Blekinge and parts of Norwegian Bohuslän were taken. In March, Christian II was deposed by a Danish uprising and Frederick I was elected King of Denmark. As a result, Lübeck's interest in cooperating with Gustav in the conquest of Scania waned, and the campaign was halted.[7]

Kalmar fell on 27 May 1523. Gustav Eriksson (Vasa) was proclaimed King of Sweden at the Riksdag in Strängnäs on 6 June 1523.

Stockholm was taken on June 17, and on Midsummer's Eve, June 23, 1523, the newly crowned King Gustav entered the capital. Throughout the summer and fall, the remaining fortresses in the Finnish part of the country surrendered,[8] and in late fall Gustav launched an unsuccessful attempt to capture Gotland from Denmark.[9]

1523 – Change of power in Denmark

editThe events in Sweden raised questions about the regime of Christian II in Denmark. After the executions during the Stockholm bloodbath, his relationship with the Church, both in Rome and in Denmark, became strained. In a failed attempt to create a scapegoat, he executed his advisor Didrik Slagheck, whom he had recently appointed Archbishop of Lund, in January 1522. Christian also enforced a new national land law that limited the power of the nobility and established hereditary royal power. In response, the bishops and councilors of Jutland called for an uprising against Christian. After unsuccessful negotiations, Christian left Denmark in April 1523 and sailed for the Netherlands with his family and his unpopular advisor, Sigbrit Willoms.[10] The rebels' candidate for the royal crown was Christian's uncle, Frederik av Gottorp, who was crowned King Frederick I of Denmark on 7 August 1524.

Christian had attempted to limit the power of Lübeck and the Hanseatic League and to make Copenhagen a free staple city and trading center. However, with Frederik's accession to power, which effectively took place in April 1523, this policy changed. Lübeck, which had supported the Danish rebellion, was promised freedom from tariffs not only in Denmark and Norway, but also in Sweden. Initially, Frederick had plans to assert his authority as king in Sweden as well, but he abandoned these plans when Lübeck did not provide the support he expected. Lübeck had no interest in a revived Nordic Union, preferring to maintain good political relations and trade terms with all the Nordic countries.[11]

1524 – Peace

editGustav Vasa and Frederik I met in Malmö in August 1524, mediated by Lübeck. Shortly thereafter, a peace treaty was negotiated that gave Lübeck and the Hanseatic League responsibility for determining the long-term status of the eastern Danish provinces. This agreement, known as the Malmö Recess, was finalized on 1 September 1524.[8][12] The result was that Blekinge, Skåne, and Gotland would remain under Danish control, while Sweden ceded its conquest of northern Bohuslän to Norway.

Aftermath

editThe Count's Feud in Denmark 1536 – The Catholic Church and the Hanseatic League runs out of money

editThe Swedish War of Liberation ended with the Count's Feud in Skåne and Denmark in 1536, resulting in the victory of Christian III with the support of Gustav Vasa's Sweden.

The financial resources of the Catholic Church and the Hanseatic League were exhausted, leading to the end of their influence in the Nordic countries. This period also marked the beginning of the Lutheran Reformation in Sweden, coinciding with similar reforms in Denmark. The once powerful and influential Hanseatic League, which had held sway for centuries, gradually receded from the political landscape and found itself on the wrong side of history in the final stages of the war.

The new Baltic competition emerges

editThe resolution of old issues was finally achieved through the understanding between Gustav Vasa and Christian III, which led to a 25-year period of peace during their reigns.

After the deaths of Christian III and Gustav Vasa in 1559 and 1560, respectively, Sweden and Denmark-Norway were ruled by young and assertive monarchs: Eric XIV of Sweden and Frederick II of Denmark–Norway. Frederick II sought to revive the Kalmar Union under Danish leadership, while Eric sought to diminish Denmark–Norway's dominant position.[13]

By 1563, during the Northern Seven Years' War, Sweden and Denmark–Norway emerged as competitors for political and economic control of the Baltic region. In 1561, when a significant portion of the Order's northern Baltic states were secularized by Grand Master Gotthard Kettler, both Denmark–Norway and Sweden were drawn into the Livonian War,[14] marking the beginning of a competition that would continue through five major conflicts between the two countries until the Scanian War in 1679.

The Lutheran Reformation

editThe dependencies were strong and the pope was firm, which resulted in Sweden being under papal interdict for fifteen years. As a result, the Lutheran Reformation took root in Sweden. The regent was presented with an irresistible proposal by the Lutherans: a state church in which the clergy would serve as the king's civil servants, thereby severing ties with the Catholic Church indefinitely. The nationalization of the Catholic Church's assets provided funds for the new ruler's regime.

The sovereign Swedish state

editThis section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (January 2024) |

Five centuries later, it remains a significant national "paradigm shift".

The war freed Sweden from international economic and political dependencies, as well as the influence of outspoken enemies. This independence has lasted for 500 years, marked by local security and peace since 1523, with foreign armies absent from its soil except in border areas. There has also been general peace for over 200 years since 1814. The War of Liberation is widely revered by Swedes as the catalyst for their political and economic independence, shaping the structure and organization of their society today. Swedes see it as a national "paradigm shift", marking a radical change in social perspectives that still underpins the foundations of their society.

Battles

edit- Battle of Falun (February 1521)

- Battle of Brunnbäck Ferry (April 1521)

- Battle of Västerås (29 April 1521)

- Conquest of Uppsala (18 May 1521)

- Conquest of Kalmar (27 May 1523)

- Conquest of Stockholm (16–17 June 1523)

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Deposed in 1523

References

edit- ^ Margareta Skantze ”Där brast ett ädelt hjärta: Kung Kristian II och hans värld” (”There a noble heart broke. King Christian II and his world”) ISBN 9789197868136

- ^ Larsson (2002) page 60

- ^ Lars-Olof Larsson (2002) page 46, Gustav Vasa – landsfader eller tyrann? 2002 Prisma ISBN 91-518-3904-0 SELIBR 8595623.

- ^ Dick Harrison (15 June 2010). "Åkte Gustav Vasa verkligen Vasaloppet?". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Gustav Vasa couldn't ski?". Gustav Vasa in Dalarna. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ Larsson (2002) pages 66–67

- ^ Larsson (2002) pages 71–72

- ^ a b Befrielsekriget 1521–1523 Archived 2 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Svenskt Militärhistoriskt Bibliotek

- ^ Larsson (2002) pages 106–107

- ^ "888 (Salmonsens konversationsleksikon / Anden Udgave / Bind IV: Bridge—Cikader)". runeberg.org.

- ^ Larsson (2002) pages 70–72

- ^ Larsson (2002) page 108

- ^ Knud J. V. Jespersen, "The Dano-Swedish Wars" Archived 2010-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 7 March 2008

- ^ När Hände Vad?: Historisk uppslagsbok 1500–2002 (2002) pp. 42

- "Sweden". Myths of the Nations. Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- Sundberg, Ulf (1998). "Befrielsekriget 1521–1523". Svenskt Militärhistoriskt Bibliotek (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Ganse, Alexander. "Swedish War of Liberation, 1521–1523". World History at KMLA. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- Henrikson, Alf. "Svensk Historia". pp. 205–213. Retrieved 25 December 2009.