Simeon Stylites or Symeon the Stylite[n 1] (Greek: Συμεών ό Στυλίτης; Syriac: ܫܡܥܘܢ ܕܐܣܛܘܢܐ, romanized: Šimʕun dʼAstˁonā; Arabic: سمعان العمودي, romanized: Simʿān al-ʿAmūdī c. 390 – 2 September 459) was a Syrian Christian ascetic, who achieved notability by living 36 years on a small platform on top of a pillar near Aleppo (in modern Syria). Several other stylites later followed his model (the Greek word style means "pillar"). Simeon is venerated as a saint by the Eastern Catholic Churches, Oriental Orthodox Churches, Eastern Orthodox Church, and Roman Catholic Church. He is known formally as Simeon Stylites the Elder to distinguish him from Simeon Stylites the Younger, Simeon Stylites III and Symeon Stylites of Lesbos.

Simeon Stylites | |

|---|---|

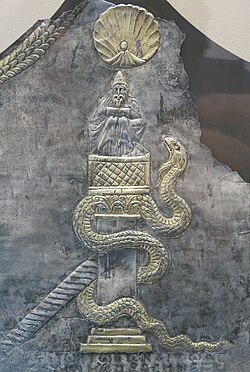

6th century depiction of Simeon on his column. A scallop shell symbolizing spiritual purity blesses Simeon; the serpent represents demonic temptations (Louvre). | |

| Venerable Father | |

| Born | c. 390 Sis, Cilicia, Roman Empire |

| Died | 2 September 459 (aged 68–69)[1][2] Qalaat Semaan, Byzantine Syria (between Aleppo and Antioch) |

| Venerated in | |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Clothed as a monk in monastic habit, shown standing on top of his pillar |

Sources

editThere exist three major early biographies of Simeon. The first of these is by Theodoret, bishop of Cyrrhus, and is found within his work Religious History. This biography was written during Simeon's lifetime, and Theodoret relates several events of which he claims to be an eyewitness. The narrator of a second biography names himself as Antonius, a disciple of Simeon's. This work is of unknown date and provenance. The third is a Syriac source, which dates to 473. This is the longest of the three, and the most effusive in its praise of Simeon; it places Simeon on a par with the Old Testament prophets, and portrays him as a founder of the Christian Church. The three sources exhibit signs of independent development; although they each follow the same rough outline, they have hardly any narrative episodes in common.[3]

All three sources have been translated into English by Robert Doran.[4] The Syriac life has also been translated by Frederick Lent.[5]

It is possible that traditional sources for the life of Simeon Stylites misrepresent his relation to Chalcedonian Christianity. Syriac letters in the British Museum attributed to Simeon Stylites indicate that he was a Miaphysite and opposed the result of the Chalcedonian council (Council of Chalcedon AD 451).[6]

Life

editEarly life

editSimeon was the son of a shepherd.[7] He was born in Sis, now the Turkish town of Kozan in Adana Province. Sis was in the Roman province of Cilicia. After the division of the Roman Empire in 395 A.D., Cilicia became part of the Eastern Roman Empire. Christianity took hold quickly there.

According to Theodoret, Simeon developed a zeal for Christianity at the age of 13, following a reading of the Beatitudes. He entered a monastery before the age of 16. From the first day, he gave himself up to the practice of an austerity so extreme that his brethren judged him to be unsuited to any form of community life.[2] They asked Simeon to leave the monastery.

He shut himself up in a hut for one and a half years, where he passed the whole of Lent without eating or drinking. When he emerged from the hut, his achievement was hailed as a miracle.[8] He later took to standing continually upright so long as his limbs would sustain him.

After one and a half years in his hut, Simeon sought a rocky eminence on the slopes of what is now the Sheik Barakat Mountain, part of Mount Simeon. He chose to live within a narrow space, less than 20 meters in diameter. But crowds of pilgrims invaded the area to seek him out, asking his counsel or his prayers, and leaving him insufficient time for his own devotions. This eventually led him to adopt a new way of life.[2]

Atop the pillar

editIn order to get away from the ever-increasing number of people who came to him for prayers and advice, leaving him little if any time for his private austerities, Simeon discovered a pillar which had survived among ruins in nearby Telanissa (modern-day Taladah in Syria),[9][10] and formed a small platform at the top. He determined to live out his life on this platform. For sustenance, small boys from the nearby village would climb up the pillar and pass him parcels of flat bread and goats' milk. He may also have pulled up food in buckets via a pulley.[citation needed]

When the monastic Elders living in the desert heard about Simeon, who had chosen a new and strange form of asceticism, they wanted to test him to determine whether his extreme feats were founded in humility or pride. They decided to order Simeon under obedience to come down from the pillar. They decided that if he disobeyed, they would forcibly drag him to the ground, but if he was willing to submit, they were to leave him on his pillar. Simeon displayed complete obedience and humility, and the monks told him to stay where he was.

The first pillar that Simeon occupied was little more than 3 meters (10 ft). He later moved his platform to others, the last in the series reportedly more than 15 meters (50 ft) from the ground.[2] At the top of the pillar was a platform, which is believed to have been about one square meter and surrounded by a baluster.

Edward Gibbon in his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire describes Simeon's life as follows:

In this last and lofty station, the Syrian Anachoret resisted the heat of thirty summers and the cold of as many winters. Habit and exercise instructed him to maintain his dangerous situation without fear or giddiness, and successively to assume the different postures of devotion. He sometimes prayed in an erect attitude, with his outstretched arms in the figure of a cross, but his most familiar practice was that of bending his meagre skeleton from the forehead to the feet; and a curious spectator, after numbering twelve hundred and forty-four repetitions, at length desisted from the endless account. The progress of an ulcer in his thigh might shorten, but it could not disturb this celestial life; and the patient Hermit expired, without descending from his column.[11]

Even on the highest of his columns, Simeon was not withdrawn from the world. If anything, the new pillar attracted even more people, both pilgrims who had earlier visited him and sightseers as well. Simeon was available each afternoon to talk with visitors. By means of a ladder, visitors were able to ascend within speaking distance. It is known that he wrote letters, the text of some of which have survived to this day, that he instructed disciples, and that he also lectured to those assembled beneath.[12] He especially preached against profanity and usury. In contrast to the extreme austerity that he practiced, his preaching conveyed temperance and compassion and was marked with common sense and freedom from fanaticism.

Much of Simeon's public ministry, like that of other Syrian ascetics, can be seen as socially cohesive in the context of the Roman East. In the face of the withdrawal of wealthy landowners to the large cities, holy men such as Simeon acted as impartial and necessary patrons and arbiters in disputes between peasant farmers and within the smaller towns.[13]

Fame and final years

editReports of Simeon reached the church hierarchy and the imperial court. The Emperor Theodosius II and his wife Aelia Eudocia greatly respected Simeon and listened to his counsels, while the Emperor Leo I paid respectful attention to a letter he sent in favour of the Council of Chalcedon. Simeon is also said to have corresponded with Genevieve of Paris.

Patriarch Domninos II (441–448) of Antioch visited the monk and celebrated the Divine Liturgy on the pillar.[14]

Evagrius Scholasticus reports an instance in which, after a wave of anti-Jewish violence in Antioch, the emperor's prefect Asclepiodotus issued a decree that any property stolen from Jews should be returned to them, and any synagogues seized and converted to churches should be restored. When Simeon heard of this, he wrote a letter to the emperor Theodosius which is recorded in the Syriac Life of Simeon:

Because in the pride of your heart you have forgotten the Lord your God, who gave you the crown of majesty and the royal throne, and have become a friend and comrade and abettor of the unbelieving Jews; know that of a sudden the righteous judgment of God will overtake you and all those 'who are of one mind with you in this matter. Then you will lift up your hands to heaven, and say in your distress, Of a truth because I dealt falsely with the Lord God this punishment has come upon me.

Theodosius then revoked the edict, fired Asclepiodotus and sent a humble reply to Simeon.[15][16] Theodoret does not explicitly mention this incident, although he praises Simeon for "defeating the insolence of the Jews". Theodor Nöldeke doubted its historicity.

Once when Simeon was ill, Theodosius sent three bishops to beg him to come down and allow himself to be attended by physicians, but Simeon preferred to leave his cure in the hands of God, and before long he recovered.

A double wall was raised around him to keep the crowd of people from coming too close and disturbing his prayerful concentration. Women were, in general, not permitted beyond the wall, not even his own mother, whom he reportedly told, "If we are worthy, we shall see one another in the life to come". She submitted to this, remaining in the area, and embraced the monastic life of silence and prayer. When she died, Simeon asked that her coffin be brought to him, and he reverently bade farewell to his dead mother.[14]

Accounts differ with regard to how long Simeon lived upon the pillar, with estimates ranging from 35 to 42 years.[12] He died on 2 September 459. A disciple found his body stooped over in prayer. The Patriarch of Antioch, Martyrius, performed the funeral of the monk before a huge crowd. He was buried not far from the pillar.[14]

Legacy

editSimeon inspired many imitators. For the next century, ascetics living on pillars, stylites, were a common sight throughout the Christian Levant.

He is commemorated as a saint in the Coptic Orthodox Church, where his feast is on 29 Pashons. He is commemorated 1 September by the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, and 5 January in the Roman Catholic Church.

A contest arose between Antioch and Constantinople for the possession of Simeon's remains. The preference was given to Antioch, and the greater part of his relics were left there as a protection to the unwalled city. Pilgrim tokens for Simeon Stylites have been found across the Byzantine Empire, attesting to the popularity of his cult.

The ruins of the vast edifice erected in his honour and known in Arabic as the Qalaat Semaan ("the Fortress of Simeon") can still be seen. They are located about 30 km northwest of Aleppo (36°20′03″N 36°50′38″E / 36.33417°N 36.84389°E) and consist of four basilicas built out from an octagonal court towards the four points of the compass to form a large cross. In the centre of the court stands the base of the style or column on which Simeon stood. On 12 May 2016, the pillar within the church reportedly took a hit from a missile, fired from what appeared to be Russian jets backing the Syrian government.[17]

Cultural references

editThe life of Simeon Stylites inspired an 1842 poem by Alfred Tennyson, "St. Simeon Stylites".[18] Modern works based upon the life of the saint include Luis Buñuel's 1965 film Simón del desierto, Hans Zender's 1986 opera Stephen Climax and the 1998 film At Sachem Farm.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Classical Syriac: ܫܡܥܘܢ ܕܐܣܛܘܢܐ šamʻun dasṯonáyá, Koine Greek Συμεὼν ὁ Στυλίτης Symeón ho Stylítes, Arabic: سمعان العمودي Simʿān al-ʿAmūdī

References

edit- ^ "Saint Simeon Stylites". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Thurston, H. (1912). "St. Simeon Stylites the Elder". The Catholic Encyclopedia – via New Advent.

- ^ Doran, Robert (1992). The Lives of Simeon Stylites. Cistercian Publications. pp. 36–66. ISBN 9780879074128.

- ^ Doran 1992, pp. 67–198

- ^ Lent, Frederick (1915). "The Life of St. Simeon Stylites". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 35. doi:10.2307/592644. JSTOR 592644.

- ^ Torrey, Charles C. (1899). "The Letters of Simeon the Stylite". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 20: 253–276. doi:10.2307/592334. JSTOR 592334.

- ^ Boner, C. (Summer 2008). "Saint Simeon the Stylite". Sophia. 38 (3). The Eparchy of Newton for the Melkite Greek Catholics: 32. ISSN 0194-7958.

- ^ Lent 1915, p. 132

- ^ Boulanger, Robert (1966). The Middle East, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran. Hachette. p. 405.

- ^ McPheeters, William, ed. (1902). Christian Faith and Life. Vol. 5. The R. L. Byran Company. p. 330.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward. "Chapter XXXVII: Conversion Of The Barbarians To Christianity". The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. 4.

- ^ a b Mann, Mimi (October 21, 1990). "Stump Is Reminder of Hermit Who Perched on Pillar for 42 Years". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014.

- ^ Brown, Peter (1971). "The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity". Journal of Roman Studies. 61: 80–101. doi:10.2307/300008. JSTOR 300008. S2CID 163463120.

- ^ a b c "St Simeon Stylites, the Elder". Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ Evagrius Scholasticus. Ecclesiastical History (AD431-594), Book 2. Translated by E. Walford. ISBN 978-0353453159.

- ^ Charles C. Torrey. The Letters of Simeon the Stylite.

- ^ Sanidopoulos, John (1 September 2017). "The Column of Saint Symeon the Stylite in Aleppo Bombed". Orthodox Christianity Then and Now.

- ^ "St. Simeon Stylites". St. Simeon Stylites by Alfred Tennyson. Wikisource. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

Further reading

edit- Attwater, Donald; John, Catherine R. (1995). The Penguin Dictionary of Saints (3rd ed.). New York: Penguin Books. pp. 322–323. ISBN 0-14-051312-4.

- Brown, Peter (1971), "The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity", The Journal of Roman Studies 61, pp. 80–101.

- Kociejowski, Marius (2004). "A Likeness of Angels". The Street Philosopher and the Holy Fool: A Syrian Journey. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 9780750938068.

External links

edit- "Canon to Saint Symeon Stylites" (from the Menaion), University of Balamand.

- "Qalaat Samaan and the Dead Cities", Syria Gate.