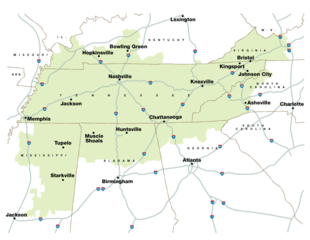

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia. While owned by the federal government, TVA receives no taxpayer funding and operates similarly to a private for-profit company. It is headquartered in Knoxville, Tennessee, and is the sixth-largest power supplier and largest public utility in the country.[3][4]

Logo of the TVA  Flag of the TVA | |

From top down and left to right: TVA's twin tower administrative headquarters in Knoxville, TVA's power operations headquarters in Chattanooga, and a map of TVA's service area | |

| Company type | State-owned enterprise |

|---|---|

| Industry | Electric utility |

| Founded | May 18, 1933 |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | Knoxville, Tennessee, U.S. |

Key people | Joe Ritch, Chair[1] Jeff Lyash, CEO[2] |

| Revenue | |

| Owner | Federal government of the United States |

| Website | tva.com |

The TVA was created by Congress in 1933 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. Its initial purpose was to provide navigation, flood control, electricity generation, fertilizer manufacturing, regional planning, and economic development to the Tennessee Valley, a region that had suffered from lack of infrastructure and even more extensive poverty during the Great Depression than other regions of the nation. TVA was envisioned both as a power supplier and a regional economic development agency that would work to help modernize the region's economy and society. It later evolved primarily into an electric utility.[5] It was the first large regional planning agency of the U.S. federal government, and remains the largest.

Under the leadership of David E. Lilienthal, the TVA also became the global model for the United States' later efforts to help modernize agrarian societies in the developing world.[6][7] The TVA historically has been documented as a success in its efforts to modernize the Tennessee Valley and helping to recruit new employment opportunities to the region. Historians have criticized its use of eminent domain and the displacement of over 125,000 Tennessee Valley residents to build the agency's infrastructure projects.[8][9][10]

Operation

editThe Tennessee Valley Authority is a government-owned corporation created by U.S. Code Title 16, Chapter 12A, the Tennessee Valley Authority Act of 1933. It was initially founded as an agency to provide general economic development to the region through power generation, flood control, navigation assistance, fertilizer manufacturing, and agricultural development. Since the Depression years, it has developed primarily into a power utility. Despite its shares being owned by the federal government, TVA operates like a private corporation, and receives no taxpayer funding.[11] The TVA Act authorizes the company to use eminent domain.[12]

TVA provides electricity to approximately ten million people through a diverse portfolio that includes nuclear, coal-fired, natural gas-fired, hydroelectric, and renewable generation. TVA sells its power to 153 local power utilities, 58 direct-serve industrial and institutional customers, 7 federal installations, and 12 area utilities.[13] In addition to power generation, TVA provides flood control with its 29 hydroelectric dams. Resulting lakes and other areas also allow for recreational activities. The TVA also provides navigation and land management along rivers within its region of operation, which is the fifth-largest river system in the United States, and assists governments and private companies on economic development projects.[11]

TVA's headquarters are located in Downtown Knoxville, with large administrative offices in Chattanooga (training/development; supplier relations; power generation and transmission) and Nashville (economic development) in Tennessee and Muscle Shoals, Alabama. TVA's headquarters were housed in the Old Customs House in Knoxville from 1936 until 1976, when the current complex opened. The building is now operated as a museum and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[14]

The Tennessee Valley Authority Police is the primary law enforcement agency for the company. Initially part of the TVA, in 1994 the TVA Police was authorized as a federal law enforcement agency.

Board of directors

editThe Tennessee Valley Authority is governed by a nine-member part-time board of directors, nominated by the president of the United States and confirmed by the Senate.[1] A minimum of seven of the directors are required to be residents of TVA's service area. The members select the chair from their number, and serve five-year terms.[a] They receive annual stipends of $45,000 ($50,000 for the chair). The board members choose the TVA's chief executive officer.[15] When their terms expire, directors may remain on the board until the end of the current congressional session (typically in December) or until their successors take office, whichever comes first.[11]

Board members

editThe current board members as of January 4, 2023:

| Position | Name | State | Appointed by | Sworn in | Term expires |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chairman | Joe H. Ritch | Alabama | Joe Biden | January 4, 2023 | May 18, 2025 |

| Member | Brian Noland | Tennessee | Donald Trump | December 31, 2020 | May 18, 2024 |

| Member | Beth Harwell | Tennessee | Donald Trump | January 5, 2021 | May 18, 2024 |

| Member | Beth Prichard Geer | Tennessee | Joe Biden | January 4, 2023 | May 18, 2026 |

| Member | Robert P. Klein | Tennessee | Joe Biden | January 4, 2023 | May 18, 2026 |

| Member | L. Michelle Moore | Georgia | Joe Biden | January 4, 2023 | May 18, 2026 |

| Member | Adam Wade White | Kentucky | Joe Biden | January 4, 2023 | May 18, 2027 |

| Member | William J. Renick | Mississippi | Joe Biden | January 4, 2023 | May 18, 2027 |

| Member | Vacant | May 18, 2028 |

Nominations

editPresident Biden has nominated the following to fill a seat on the board. They await Senate confirmation.[16]

| Name | State | Term expires | Replacing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patrice J. Robinson | Tennessee | May 18, 2028 | William B. Kilbride |

Power generation

editPower stations

editWith a generating capacity of approximately 35 gigawatts (GW), TVA has the sixth highest generation capacity of any utility company in the United States and the third largest nuclear power fleet, with seven units at three sites.[3][17] In addition, they also operate four coal-fired power plants, 29 hydroelectric dams, nine simple-cycle natural gas combustion turbine plants, nine combined cycle gas plants, 1 pumped storage hydroelectric plant, 1 wind energy site, and 14 solar energy sites.[18] In fiscal year 2020, nuclear generation made up about 41% of TVA's total energy production, natural gas 26%, coal 14%, hydroelectric 13%, and wind and solar 3%.[18] TVA purchases about 15% of the power it sells from other power producers, which includes power from combined cycle natural gas plants, coal plants, and wind installations, and other renewables.[19] The cost of Purchased Power is part of the "Fuel Cost Adjustment" (FCA) charge that is separate from the TVA Rate. In addition, the Watts Bar Nuclear Plant is the only facility in the country to industrially produce tritium, which is used by the National Nuclear Security Administration for nuclear weapons, where it is used to supercharge and boost the explosive yield of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.[20]

Electric transmission

editTVA owns and operates its own electric grid, which consists of approximately 16,200 miles (26,100 km) of lines, one of the largest grids in the United States. This grid is part of the Eastern Interconnection of the North American power transmission grid, and is under the jurisdiction of the SERC Reliability Corporation.[21] Like most North American utilities, TVA uses a maximum transmission voltage of 500 kilovolts (kV), with lines carrying this voltage using bundled conductors with three conductors per phase. The vast majority of TVA's transmission lines carry 161 kV, with the company also operating a number of sub-transmission lines with voltages of 69 kV and 46kV. They also operate a small number of 115kV and 230kV lines in Alabama and Georgia that connect to Southern Company lines of the same voltage.[22][23]

Recreation

editTVA has conveyed approximately 485,420 acres (1,964.4 km2) of property for recreation and preservation purposes including public parks, public access areas and roadside parks, wildlife refuges, national parks and forests, and other camps and recreation areas, comprising approximately 759 different sites.[24]

Currently, TVA manages approximately 293,000 acres (1,190 km2) of Federally-owned land for public use. These lands are managed as either TVA Natural Areas or TVA Day-Use Recreation Areas. Natural Areas are smaller, ecologically or historically significant areas set aside for conservation, with some areas including hiking and walking trails. Day-Use Recreation Areas comprise approximately 80 different locations throughout the Tennessee Valley largely concentrated on or near TVA reservoirs that include water access points, campgrounds, hiking trails, fishing piers, and equestrian facilities.[25][26]

Economic development

editTVA operates an economic development organization that works with companies and economic development agencies throughout the Tennessee Valley to create jobs via private investments. They also work with businesses to help them choose locations for facilities and expand existing facilities. Services provided include assistance with site selection, employee recruitment and training, and research.[27] A total of seven sites throughout the Valley are certified by TVA as megasites, which contain a minimum of 1,000 acres (4.0 km2), and have access to an Interstate Highway and the potential for rail service, and environmental impact study, and contain or have the potential to contain direct-serve industrial customers.[28]

History

editBackground

editIn the late 19th century, the Army Corps of Engineers first recognized a number of potential dam sites along the Tennessee River for electricity generation and navigation improvements.[29] The National Defense Act of 1916, signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, authorized the construction of a hydroelectric dam on the Tennessee River in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, for the purpose of producing nitrates for ammunition. During the 1920s and the 1930s, Americans began to support the idea of public ownership of utilities, particularly hydroelectric power facilities. Many believed privately owned power companies were charging too much for power, did not employ fair operating practices, and were subject to abuse by their owners, utility holding companies, at the expense of consumers.[citation needed] The concept of government-owned generation facilities selling to publicly owned distribution utilities was controversial, and remains so today.[30] The private sector practice of forming utility holding companies had resulted in them controlling 94 percent of generation by 1921, and they were essentially unregulated. In an effort to change this, Congress and Roosevelt enacted the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA).[31]

During his 1932 presidential campaign, Franklin D. Roosevelt expressed his belief that private utilities had "selfish purposes" and said, "Never shall the federal government part with its sovereignty or with its control of its power resources while I'm President of the United States."

U.S. Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska also distrusted private utility companies, and in 1920 blocked a proposal from industrialist Henry Ford to build a private dam and create a utility to modernize the Tennessee Valley.[32] In 1930, Norris sponsored the Muscle Shoals Bill, which would have built a federal dam in the valley, but it was vetoed by President Herbert Hoover, who believed it to be socialistic.[33]

The idea behind the Muscle Shoals project became a core part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal program that created the Tennessee Valley Authority.[34]

Even by Depression standards, the Tennessee Valley was in dire economic straits in 1933. Thirty percent of the population was affected by malaria. The average income in the rural areas was $639 per year (equivalent to $11,947 in 2024),[35] with some families surviving on as little as $100 per year (equivalent to $1,870 in 2023).[35]

Much of the land had been exhausted by poor farming practices, and the soil was eroded and depleted. Crop yields had fallen, reducing farm incomes. The best timber had been cut, and 10% of forests were lost to fires each year.[30]

Founding and early history

editPresident Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act (ch. 32, Pub. L. 73–17, 48 Stat. 58, enacted May 18, 1933, codified as amended at 16 U.S.C. § 831, et seq.), creating the TVA. The agency was initially tasked with modernizing the region, using experts and electricity to combat human and economic problems.[36] TVA developed fertilizers, and taught farmers ways to improve crop yields.[37] In addition, it helped replant forests, control forest fires, and improve habitats for fish and wildlife.

The Authority hired many of the area's unemployed for a variety of jobs: they conducted conservation, economic development, and social programs. For instance, a library service was instituted for this area. The professional staff at headquarters were generally composed of experts from outside the region. By 1934, TVA employed more than 9,000 people.[38] The workers were classified by the usual racial and gender lines of the region, which limited opportunities for minorities and women. TVA hired a few African Americans, generally restricted for janitorial or other low-level positions. TVA recognized labor unions; its skilled and semi-skilled blue collar employees were unionized, a breakthrough in an area known for corporations hostile to miners' and textile workers' unions. Women were excluded from construction work.

Many local landowners were suspicious of government agencies, but TVA successfully introduced new agricultural methods into traditional farming communities by blending in and finding local champions. Tennessee farmers often rejected advice from TVA officials, so the officials had to find leaders in the communities and convince them that crop rotation and the judicious application of fertilizers could restore soil fertility.[39] Once they had convinced the leaders, the rest followed.[37]

TVA immediately embarked on the construction of several hydroelectric dams, with the first, Norris Dam in upper East Tennessee, breaking ground on October 1, 1933. These facilities, designed with the intent of also controlling floods, greatly improved the lives of farmers and rural residents, making their lives easier and farms in the Tennessee Valley more productive. They also provided new employment opportunities to the poverty-stricken regions in the Valley. At the same time, however, they required the displacement of more than 125,000 valley residents or roughly 15,000 families,[8] as well as some cemeteries and small towns, which caused some to oppose the projects, especially in rural areas.[9][40] The projects also inundated several Native American archaeological sites, and graves were reinterred at new locations, along with new tombstones.[41][42]

The available electricity attracted new industries to the region, including textile mills, providing desperately needed jobs, many of which were filled by women.[5][43] A few regions of the Tennessee Valley did not receive electricity until the late 1940s and early 1950s, however. TVA was one of the first federal hydropower agencies, and was quickly hailed as a success. While most of the nation's major hydropower systems are federally managed today, other attempts to create similar regional corporate agencies have failed. The most notable was the proposed Columbia Valley Authority for the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest, which was modeled off of TVA, but did not gain approval.[44]

World War II

editIn order to provide the power for essential industries during World War II, TVA engaged in one of the largest hydropower construction programs ever undertaken in the U.S. This was especially important for the energy-intensive aluminum industry, which was used in airplanes and munitions.[45] By early 1942, when the effort reached its peak, 12 hydroelectric plants and one coal-fired steam plant were under construction at the same time, and design and construction employment reached a total of 28,000. In its first eleven years, TVA constructed a total of 16 hydroelectric dams. During the war, the agency also provided 60% of the elemental phosphorus used in munitions, produced maps of approximately 500,000 square miles (1,300,000 km2) of foreign territory using aerial reconnaissance, and provided mobile housing for war workers.[38]

The largest project of this period was the Fontana Dam. After negotiations led by then-Vice President Harry Truman, TVA purchased the land from Nantahala Power and Light, a wholly owned subsidiary of Alcoa, and built Fontana Dam. Also in 1942, TVA's first coal-fired plant, the 267-megawatt Watts Bar Steam Plant, began operation.[46] The government originally intended the electricity generated from Fontana to be used by Alcoa factories for the war effort. However, the abundance of TVA power was one of the major factors in the decision by the U.S. Army to locate uranium enrichment facilities in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, for the world's first atomic bombs.[47][48] This was part of an effort codenamed the Manhattan Project.[49][50]

Increasing power demand

editBy the end of World War II, TVA had completed a 650-mile (1,050 km) navigation channel the length of the Tennessee River and had become the nation's largest electricity supplier.[51] Even so, the demand for electricity was outstripping TVA's capacity to produce power from hydroelectric dams, and so TVA began to construct additional coal-fired plants. Political interference kept TVA from securing additional federal appropriations to do so, so it sought the authority to issue bonds.[52] Several of TVA's coal-fired plants, including Johnsonville, Widows Creek, Shawnee, Kingston, Gallatin, and John Sevier, began operations in the 1950s.[53] In 1955 coal surpassed hydroelectricity as TVA's top generating source.[54] On August 6, 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law an amendment to the TVA act, making the agency self-financing.[55] During the 1950s, TVA's generating capacity nearly quadrupled.[22]

The 1960s were years of further unprecedented economic growth in the Tennessee Valley. Capacity growth during this time slowed, but ultimately increased 56% between 1960 and 1970.[22] To handle a projected future increase in electrical consumption, TVA began constructing 500 kilovolt (kV) transmission lines, the first of which was placed into service on May 15, 1965.[22] Electric rates were among the nation's lowest during this time and stayed low as TVA brought larger, more efficient generating units into service. Plants completed during this time included Paradise, Bull Run, and Nickajack Dam.[22] Expecting the Valley's electric power needs to continue to grow, TVA began building nuclear power plants in 1966 as a new source of power.[56] The following year, TVA began work on the construction of Tellico Dam, which had been initially conceived in the 1930s and would later become its most controversial project.[57][58][59]

Financial problems, Tellico Dam, and restructuring

editDuring the 1970s significant changes occurred in the economy of the Tennessee Valley and the nation, prompted by energy crises in 1973 and 1979 and accelerating fuel costs throughout the decade. The average cost of electricity in the Tennessee Valley increased fivefold from the early 1970s to the early 1980s. TVA's first nuclear reactor, Browns Ferry Unit 1, began commercial operation on August 1, 1974.[62] Between 1970 and 1974, TVA set out to construct a total of 17 nuclear reactors, due to a projection of further rapid increase in power demand.[63] However, in the 1980s, it became increasingly evident that the agency had vastly overestimated the Valley's future energy needs, and rapid increases in construction costs and new regulations following the Three Mile Island accident posed additional obstacles to this undertaking.[64][65] In 1981, the board voted to defer the Phipps Bend plant, as well as to slow down construction on all other projects.[66] The Hartsville and Yellow Creek plants were cancelled in 1984 and Bellefonte in 1988.[63] Citing safety concerns, all of TVAs five operating nuclear reactors were indefinitely shut down in 1985 with the two at Sequoyah coming back online three years later and Browns Ferry's three reactors coming back online in 1991, 1995 and 2007. [64][67]

Construction of the Tellico Dam raised political and environmental concerns, as laws had changed since early development in the valley. Scientists and other researchers had become more aware of the massive environmental effects of the dams and new lakes, and worried about preserving habitats and species. The Tellico Dam project was initially delayed because of concern over the snail darter, a small ray-finned fish which had been discovered in the Little Tennessee River in 1973 and listed as an endangered species two years later.[68] A lawsuit was filed under the Endangered Species Act and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of protecting the snail darter in Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill in 1978.[69] The project's main motive was to support recreational and tourism development, unlike earlier dams constructed by TVA. Land acquired by eminent domain for the Tellico Dam and its reservoir that encountered minimal inundation was sold to private developers for the construction of present-day Tellico Village, a planned retirement community.[70]

The inflation crises of the 1970s and early 1980s, combined with the cancellation of several of the planned nuclear plants put the agency in deep financial trouble.[71] In an effort to restructure and improve efficiency and financial stability, TVA began shifting towards a more corporate environment in the latter 1980s.[72] Marvin Travis Runyon, a former corporate executive in the automotive industry, became chairman of the TVA in January 1988, and pledged to stabilize the agency financially. During his four-year term he worked to reduce management layers, and reduced overhead costs by more than 30%, which required thousands of workers to be laid off and many operations transferred to private contractors. These moves resulted in cumulative savings and efficiency improvements of $1.8 billion (equivalent to $3.51 billion in 2023[35]).[71][72] His tenure also saw three of the agency's five nuclear reactors return to service,[73][74] and the institution of a rate freeze that continued for ten years.[75]

Early 1990s to late 2010s

editAs the electric-utility industry moved toward restructuring and deregulation, TVA began preparing for competition. It cut operating costs by nearly $800 million a year, reduced its workforce by more than half, increased the generating capacity of its plants, and developed a plan to meet the energy needs of the Tennessee Valley through 2020.[76]

In 1992 work resumed on Watts Bar Unit 1, and the reactor began operation in May 1996.[77][78] This was the last commercial nuclear reactor in the United States to begin operation in the 20th century.[79] In 2002, TVA began work to restart Browns Ferry Unit 1, the last of TVA's reactors that had been mothballed in 1985. This unit returned to service in 2007. In 2004, TVA implemented recommendations from the Reservoir Operations Study (ROS) on how it operates the Tennessee River system. The following year, the company announced its intention to construct an Advanced Pressurized Water Reactor at its Bellefonte site in Alabama, filing the necessary applications in November 2007. This proposal was gradually trimmed over the following years, and essentially voided by 2016.[65][80] In October 2007, construction resumed on Watts Bar Unit 2.[81] which began commercial operation in October 2016. Watts Bar Unit 2 was the first new nuclear reactor to enter service in the United States in the 21st century.[82]

On December 22, 2008, an earthen dike impounding a coal ash pond at TVA's Kingston Fossil Plant failed, releasing 1.1 billion US gallons (4,200,000 m3) of coal ash slurry across 300 acres (1.2 km2) of land and into two tributaries of the Tennessee River. The spill, of which cleanup was completed in 2015 at a cost of more than $1 billion, was the largest industrial spill in United States history, and considered one of the worst environmental disasters of all time.[83][84] A 2009 report by engineering firm AECOM found a number of inadequate design factors of the ash pond were responsible for the spill,[85] and in August 2012, TVA was found liable for the disaster by the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee.[86] The initial spill resulted in no injuries or deaths, but several of the employees of an engineering firm hired by TVA to clean up the spill developed illnesses, some of which were fatal,[42] and in November 2018, a federal jury ruled that the contractor did not properly inform the workers about the dangers of exposure to coal ash and had failed to provide them with necessary personal protective equipment.[87][83]

In 2009, to gain more access to sustainable, green energy, TVA signed 20-year power purchase agreements with Maryland-based CVP Renewable Energy Co. and Chicago-based Invenergy Wind LLC for electricity generated by wind farms.[88] In April 2011, TVA reached an agreement with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), four state governments, and three environmental groups to drastically reduce pollution and carbon emissions.[89] Under the terms of the agreement, TVA was required to retire at least 18 of its 59 coal-fired units by the end of 2018, and install scrubbers in several others or convert them to make them cleaner, at a cost of $25 billion, by 2021.[89] As a result, TVA closed several of its coal-fired power plants in the 2010s, converting some to natural gas. These include John Sevier in 2012, Shawnee Unit 10 in 2014, Widows Creek in 2015, Colbert in 2016, Johnsonville and Paradise Units 1 and 2 in 2017, Allen in 2018, and Paradise Unit 3 in 2020.[90]

Recent history

editIn 2018, TVA opened a new cybersecurity center in its downtown Chattanooga Office Complex. More than 20 Information Technology specialists monitor emails, Twitter feeds and network activity for cybersecurity threats and threats to grid security. Across TVA's digital platform, two billion activities occur each day. The center is staffed 24 hours a day to spot any threats to TVA's 16,000 miles of transmission lines.[92]

Given continued economic pressure on the coal industry, the TVA board defied President Donald Trump and voted in February 2019 to close two aging coal plants, Paradise Unit 3 and Bull Run. TVA chief executive Bill Johnson said the decision was not about coal, per se, but rather "about keeping rates as low as feasible". They stated that decommissioning the two plants would reduce its carbon output by about 4.4% annually.[93] TVA announced in April 2021 plans to completely phase out coal power by 2035.[94] The following month, the board voted to consider replacing almost all of their operating coal facilities with combined-cycle gas plants. Such plants considered for gas plant redevelopment include the Cumberland, Gallatin, Shawnee, and Kingston facilities.[95]

In early February 2020, TVA awarded an outside company, Framatome, several multi-million-dollar contracts for work across the company's nuclear reactor fleet.[96] This includes fuel for the Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant, fuel handling equipment upgrades across the fleet and steam generator replacements at the Watts Bar Nuclear Plant. Framatome will provide its state-of-the-art ATRIUM 11 fuel for the three boiling water reactors at Browns Ferry. This contract makes TVA the third U.S. utility to switch to the ATRIUM 11 fuel design.[96] On August 3, 2020, President Trump fired the TVA chairman and another board member, saying they were overpaid and had outsourced 200 high-tech jobs. The move came after U.S. Tech Workers, a nonprofit that works to limit visas given to foreign technology workers, criticized the TVA for laying off its own workers and replacing them with contractors using foreign workers with H-1B visas.[97]

Citing its aspiration to reach net-zero carbon emissions in 2050, the TVA Board voted to approve an advanced approach of nuclear energy technology with an estimated $200 million investment, known as the New Nuclear Program (NNP) in February 2022. This would promote the construction of new nuclear power facilities, particularly small modular reactors, with the first facility being constructed in partnership with Oak Ridge National Laboratory at the Clinch River Nuclear Site in Oak Ridge.[91][98] On December 23, 2022, TVA had several hours of rolling blackouts due to the late December 2022 North American winter storm.[99] As many as 24,000 Nashville Electric Service customers were without power, with thousands more from smaller distributors affected as well.[100][101]

Criticism and controversies

editAllegations of federal government overreach

editTVA was heralded by New Dealers and the New Deal Coalition not only as a successful economic development program for a depressed area but also as a democratic nation-building effort overseas because of its alleged grassroots inclusiveness as articulated by director David E. Lilienthal. However, the TVA was controversial early on, as some believed its creation was an overreach by the federal government.

Supporters of TVA note that the agency's management of the Tennessee River system without appropriated federal funding saves federal taxpayers millions of dollars annually. Opponents, such as Dean Russell in The TVA Idea, in addition to condemning the project as being socialistic, argued that TVA created a "hidden loss" by preventing the creation of "factories and jobs that would have come into existence if the government had allowed the taxpayers to spend their money as they wished".[102] Defenders note that TVA remains overwhelmingly popular in Tennessee among conservatives and liberals alike.[103] Business historian Thomas McCraw concludes that Roosevelt "rescued the [power] industry from its own abuses" but "he might have done this much with a great deal less agitation and ill will".[104] New Dealers hoped to build numerous other federal utility corporations around the country but were defeated by lobbyist and 1940 Republican presidential nominee Wendell Willkie and the conservative coalition in Congress. The valley authority model did not replace the limited-purpose water programs of the Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers.

However, it has been shown that in river policy, the strength of opposing interest groups also mattered.[105] The TVA bill was able to attain passage because reformers like Norris skillfully coordinated action at potential choke points and weakened the already disorganized opponents among the electric power industry lobbyists.[30] In 1936, after regrouping, opposing river lobbyists and members of congress who were part of the conservative coalition took advantage of the New Dealers' spending mood by expanding the Army Corps' flood control program. They also helped defeat further valley authorities, the most promising of the New Deal water policy reforms.[105] When Democrats after 1945 began proclaiming the Tennessee Valley Authority as a model for countries in the developing world to follow, conservative critics charged that it was a top-heavy, centralized, technocratic venture that displaced locals and did so in insensitive ways. Thus, when the program was used as the basis for modernization programs in various parts of the third world during the Cold War, such as in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, its failure brought a backlash of cynicism toward modernization programs that has persisted.[6]

In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower referred to the TVA as an example of "creeping socialism".[106][107] The following year, then-film actor and later 40th President Ronald Reagan began hosting General Electric Theater, which was sponsored by General Electric (GE). He was fired in 1962 after publicly referring to the TVA, which was a major customer for GE turbines, as one of the problems of "big government".[108] Some claim that Reagan was instead fired due to a criminal antitrust investigation involving him and the Screen Actors Guild.[109] However, Reagan was only interviewed; nobody was actually charged with anything in the investigation.[110][111] In 1963, U.S. Senator and Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater was quoted in a Saturday Evening Post article by Stewart Alsop as saying, "You know, I think we ought to sell TVA." He had called for the sale to private companies of particular parts of the Authority, including its fertilizer production and steam-generation facilities, because "it would be better operated and would be of more benefit for more people if it were part of private industry."[112] Goldwater's quotation was used against him in a TV ad by Doyle Dane Bernbach for then-President Lyndon B. Johnson's 1964 campaign, which depicted an auction taking place atop a dam and promised that Johnson would not sell TVA.[113]

Legal challenges

editThe TVA has faced multiple constitutional challenges. The United States Supreme Court ruled TVA to be constitutional in Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority (297 U.S. 288) in 1936.[114] The Court noted that regulating commerce among the states includes regulation of streams and that controlling floods is required for keeping streams navigable; it also upheld the constitutionality of the TVA under the War Powers Clause, seeing its activities as a means of assuring the electric supply for the manufacture of munitions in the event of war.[115] The argument before the court was that electricity generation was a by-product of navigation and flood control and therefore could be considered constitutional. The CEO of the Tennessee Electric Power Company (TEPCO), Jo Conn Guild, was vehemently opposed to the creation of TVA, and with the help of attorney Wendell Willkie, challenged the constitutionality of the TVA Act in federal court. The U.S. Supreme Court again upheld the TVA Act, however, in its 1939 decision Tennessee Electric Power Company v. TVA. On August 16, 1939, TEPCO was forced to sell its assets, including Hales Bar Dam, Ocoee Dams 1 and 2, Blue Ridge Dam and Great Falls Dam to TVA for $78 million (equivalent to $1.34 billion in 2023[35]).[116]

Discrimination

editIn 1981 the TVA Board of Directors broke with previous tradition and took a hard line against white-collar unions during contract negotiations. As a result, a class action suit was filed in 1984 in U.S. District Court charging the agency with sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 based on the large number of women in one of the pay grades negatively impacted by the new contract.[117] TVA reached an out-of-court settlement in 1987, in which they agreed to contract modifications and paid the group $5 million (equivalent to $11.5 million in 2023[35]), but denied wrongdoing.[118]

Eminent domain and resident removal

editTVA has received criticism throughout its entire history for what some have perceived as excessive use of its authority of eminent domain and an unwillingness to compromise with landowners. All of TVA's hydroelectric projects were made possible through the use of eminent domain,[120][121] and displaced more than 125,000 Tennessee Valley residents.[8] Residents who initially refused to sell their land were often forced to do so via court orders and lawsuits.[122][120] Many of these projects also inundated historic Native American sites and early Colonial-era settlements.[123][124][125] Historians have claimed that the TVA forced residents to sell their property at values less than the fair market value, and indirectly destabilized the real estate market for farmland.[40] Some displaced residents committed suicide, unable to bear the events.[9] On some occasions, land that TVA had acquired through eminent domain that was expected to be flooded by reservoirs was not flooded, and was instead given away to private developers.[126]

In popular culture

editThe 1960 film Wild River, directed by Elia Kazan, tells the story about a family forced to relocate from their land, which has been owned by their ancestors for generations, after TVA plans to construct a dam which will flood it. While fictional, the film depicts the real-life experiences of many people forced to give up their land to TVA to make way for hydroelectric projects, and was mostly inspired by the removal of families for the Norris Dam project.[40][127]

The 1970 James Dickey novel Deliverance and its 1972 film adaptation focuses on four Atlanta businessmen taking a canoeing trip down a river that is being impounded by an electric utility, nodding to the TVA's early and controversial hydroelectric projects.[128] The 1984 Mark Rydell film The River focuses on an East Tennessee family being confronted by the loss of their ancestral farm from the inundation of a nearby river by an electric utility. The film, shot on farmland near the Holston River in Hawkins County, utilized flooding practical effects provided by the TVA.[129] In the 2000 film O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the family home of the protagonist, played by George Clooney, is flooded by a reservoir constructed by the TVA. This plays a central role in the pacing of the film and the broader Depression-era Mississippi context of the narrative.[130]

"Song of the South" by country and Southern rock band Alabama features the lyrics "Papa got a job with the TVA" following the lyrics "Well momma got sick and daddy got down, The county got the farm and they moved to town" expressing the hardships and changes that southerners faced during the post recession era.[131] The TVA and its impact on the region are featured in the Drive-By Truckers' songs "TVA" and "Uncle Frank". In "TVA", the singer reflects on time spent with family members and a girlfriend at Wilson Dam. In "Uncle Frank", the lyrics tell the story of an unnamed hydroelectric dam being built, and the effects on the community that would become flooded upon its completion. In 2012, Jason Isbell released a solo cover of "TVA".[132]

See also

edit- Environmental history of the United States

- Appalachian Regional Commission

- Helmand and Arghandab Valley Authority, modelled on the TVA

- James Bay Energy Corporation, a Crown corporation of the Quebec government for developing the James Bay Project for building various dams on rivers

- List of navigation authorities in the United States

- Muscle Shoals Bill

- Nashville Electric Service

- New Deal

- Norris, Tennessee

- Tennessee Valley Authority Police

- Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill

Notes

edit- ^ When their terms expire, directors may remain on the board until the end of the current congressional session (typically in December) or until their successors take office, whichever comes first.

References

edit- ^ a b "Board of Directors". TVA. Archived from the original on November 22, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Gaines, Jim (February 14, 2019). "TVA names president of Canadian utility as new CEO to replace outgoing Bill Johnson". Knoxville News Sentinel. Knoxville, Tennessee. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "Factbox: Largest U.S. electric companies by megawatts, customers". Reuters. April 29, 2014. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Sainz, Adrian (November 14, 2019). "Nation's largest utility in long-term deals to sell power". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Neuse 2004, pp. 972–979.

- ^ a b Ekbladh, David (Summer 2002). ""Mr. TVA": Grass-Roots Development, David Lilienthal, and the Rise and Fall of the Tennessee Valley Authority as a Symbol for U.S. Overseas Development, 1933–1973". Diplomatic History. 26 (3): 335–374. doi:10.1111/1467-7709.00315. ISSN 1467-7709. OCLC 772657716.

- ^ "Global Impact" (PDF). Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c John Gaventa (1982). "Book Review, 'TVA and the Dispossessed: The Resettlement of Population in the Norris Dam Area'". Tennessee Law Review. Symposium, the Tennessee Valley Authority. Knoxville, Tennessee: Tennessee Law Review Association: 979–983.

Over the past fifty years the agency has had many opportunities to learn from its mistakes. Since 1933, over 125,000 residents have been displaced from their homesteads by TVA dam construction projects.

- ^ a b c Muldowny, John; McDonald, Michael (1981). TVA and the Dispossessed: The Resettlement of Population in the Norris Dam Area. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781572331648. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "The Price of Power: How the Tennessee Valley Authority Impacted Attitudes Towards Economic Development in East Tennessee". Appalachian Free Press. January 12, 2022. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c "About TVA". tva.com. Tennessee Valley Authority. 2018. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "The TVA and the Relocation of Mattie Randolph". Archives.gov. National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ "Public Power Partnerships". tva.com. Tennessee Valley Authority. 2018. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "East Tennessee Historical Society". East-tennessee-history.org. Archived from the original on June 30, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ^ "TVA Board Expanded To 9 Members". The Chattanoogan. Chattanooga, Tennessee. November 20, 2004. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "Quick Search Tennessee Valley Authority". Congress.gov. Library of Congress. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ McDermott, Jennifer (February 10, 2022). "Largest US public power company launches new nuclear program". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "Our Power System". tva.com. Tennessee Valley Authority. 2018. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "TVA: Energy Purchases from Wind Farms". TVA. Archived from the original on July 31, 2015.

- ^ Cathey, Ben (May 24, 2022). "Watts Bar lone source of a nuclear weapon material; TVA increasing production". WVLT-TV. Knoxville. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. electric system is made up of interconnections and balancing authorities". eia.gov. Energy Information Administration. July 20, 2016. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Clem, Clayton L.; Nelson, Jeffrey H. (October 2010). "The TVA Transmission System: Facts, Figures and Trends". 2010 International Conference on High Voltage Engineering and Application (Report). Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on High Voltage Engineering and Application. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1109/ichve.2010.5640878. ISBN 978-1-4244-8283-2. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021 – via Zenodo.

- ^ NERC Transmission Planning Map (PDF) (Map). North American Electric Reliability Corporation. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2021 – via Open Access Same-Time Information System.

- ^ "Chapter 8 – Recreation Management" (PDF). Natural Resource Plan. Tennessee Valley Authority. July 2011. p. 113. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 10, 2011. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ "Day-Use Recreation Areas". TVA.com. Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ "Small Wild Areas". TVA.com. Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ "The Global Valley". Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Mattson-Teig, Beth (Summer 2013). "Mega Sites Lure Big Fish". Area Development. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Hargrove 1994, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Hubbard, Preston J. (1961). Origins of the TVA: The Muscle Shoals Controversy, 1920–1932. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 189–194. OCLC 600647072. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2018 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- ^ Hawes, Douglas W. (April 1977). "Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 -- Fossil or Foil?". Vanderbilt Law Review. 30 (3): 605–625. Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ Tobey, Ronald C. (1996). Technology as Freedom: The New Deal and the Electrical Modernization of the American Home. University of California Press. pp. 46–48. ISBN 9780520204218. Retrieved July 4, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Muscle Shoals Bill Passed By Senate; Vote on Norris Measure for Operation by Federal Corporation Is 45 to 23. House Counted Favorable But Hoover Veto is Expected in Event of Passage—His Supporters Divided in Debate. Hoover Supporters Divided. The Vote on Roll-Call". The New York Times. April 5, 1930. p. 3. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Wengert, Norman (1952). "Antecedents of TVA: The Legislative History of Muscle Shoals". Agricultural History. 26 (4): 141–147. ISSN 1533-8290. JSTOR 3740474. OCLC 971899953.

- ^ a b c d e Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Schulman, Bruce J. (1991). From Cotton Belt to Sunbelt: Federal policy, economic development, and the transformation of the South, 1938–1980. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536344-9. OCLC 300412389.

- ^ a b Selznick, Philip (1953). TVA and the Grass Roots: A Study in the Sociology of Formal Organization. Los Angeles; Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 134–139. ISBN 1528359852. Archived from the original on October 6, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ a b "TVA". History.com. The History Channel. August 7, 2017. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ Shapiro, Edward (Winter 1970). "The Southern Agrarians and the Tennessee Valley Authority". American Quarterly. 22 (4): 791–806. doi:10.2307/2711870. ISSN 0003-0678. JSTOR 2711870. OCLC 5545493875.

- ^ a b c Stephens, Joseph (May 2018). "Forced Relocations Presented More of an Ordeal than an Opportunity for Norris Reservoir Families". Historic Union County. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ Creese 1990, pp. 95–105.

- ^ a b "Brackish Water". Oxford American. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Long, Jennifer (December 1999). "Government Job Creation Programs—Lessons from the 1930s and 1940s". Journal of Economic Issues. 33 (4): 903–918. doi:10.1080/00213624.1999.11506220. ISSN 0021-3624. OCLC 5996637494.

- ^ Hargrove 1994, p. 137.

- ^ Russell 1949, pp. 29–30.

- ^ "Plants of the Past". tva.com. Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ^ Russell 1949, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Creese 1990, pp. 221–231.

- ^ Fine, Lenore; Remington, Jesse A. (1972). The Corps of Engineers: Construction in the United States (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 134–135. OCLC 834187. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ Jones, Vincent (1985). Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 46–47. OCLC 10913875. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ Russell 1949, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Hargrove & Conkin 1983, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Gross, Daniel (October 2, 2015). "The Tennessee Valley Authority is closing coal plants, and that's huge". Slate Magazine. Retrieved January 7, 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The 1950s". tva.com. Tennessee Valley Authority. 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "Snapshot of major events in TVA history". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. May 11, 2008. Archived from the original on January 20, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ "TVA timeline by year" (PDF). Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ Morrissey, Connor (December 11, 2018). "The Tennessee Valley Authority: A Timeline of Controversy". Medium. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ Rawls, Wendell Jr. (November 11, 1979). "Forgotten People of the Tellico Dam Fight". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ "Telling the Story of Tellico: It's Complicated". Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Tennessee Valley Authority (January 1, 1976). Timberlake New Community: Final Environmental Statement (PDF). Chattanooga: Boston College Law School. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ Van West, Carroll (October 8, 2017). "Monroe County". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Tennessee Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ "Browns Ferry No. 2 N-Unit Test Approved". The Tennessean. Nashville, Tennessee. Associated Press. August 9, 1974. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Wald, Matthew (August 19, 2011). "Alabama Nuclear Reactor, Partly Built, to Be Finished". The New York Times. p. A12. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Labaton, Stephen (August 3, 1985). "Tennessee Valley Authority Generates Woes With Nuclear Power Program". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Davis, Will (April 17, 2015). "TVA Prepares to Write Final Nuclear Chapters". Nuclear Newswire. American Nuclear Society. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Hayes, Hank (August 23, 2008). "Nuclear power option still alive at TVA despite Phipps Bend debacle". Kingsport Times-News. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ "T.V.A., Citing Safety, to Shut Down Nuclear Plant". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 22, 1985. p. A19. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Robert (April 13, 2008). "Tellico Dam still generating debate". Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (U.S. Supreme Court June 15, 1978), archived from the original.

- ^ Rawls, Wendell (November 11, 1979). "Forgotten People of the Tellico Dam Fight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Smothers, Ronald (June 30, 1988). "T.V.A. Slashes Work Force And Holds Off on 2 Plants". The New York Times. p. A-14. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Lippman, Thomas W. (March 29, 1992). "TVA: New Deal For An Old Power". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Lippman, Thomas W. (April 11, 1990). "For TVA, It's Back to a Nuclear Future". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "TVA Ala. Browns Ferry 1, 2 reactor output rises". Reuters. August 24, 2010. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Mansfield, Duncan (July 6, 1999). "TVA Shaped Valley Over Course of Decades New Deal Agency Tamed a River, Changed Many Lives in Impoverished Rural Areas". Birmingham News.

- ^ "The 1990s". Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Gang, Duane W. (August 29, 2014). "5 things to know about TVA and nuclear power". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "WATTS BAR-1: Reactor Details". Power Reactor Information System. International Atomic Energy Agency. Archived from the original on March 13, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ Safer, Don; Barczak, Sara (October 8, 2015). "Watts Bar Unit 2, last old reactor of the 20th century: a cautionary tale". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ Derek Hawkins (September 12, 2016). "For sale: Multibillion-dollar, non-working nuclear power plant, as is". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ "WATTS BAR-2". PRIS. International Atomic Energy Agency. June 29, 2013. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ Blau, Max (October 20, 2016). "First new US nuclear reactor in 20 years goes live". CNN. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Sullivan, J.R . (September 2019). "A Lawyer, 40 Dead Americans, and a Billion Gallons of Coal Sludge". Men's Journal. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- ^ Bourne, Joel K. (February 19, 2019). "Coal's other dark side: Toxic ash that can poison water, destroy life and toxify people". National Geographic. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ Barker, Scott (June 26, 2009). "Report: Four factors led to fly ash spill". Knoxville News-Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009.

- ^ Purdom, Rebecca; Remmel, Emily (May 24, 2013). "TVA Found Liable for Massive Coal Ash Spill But Proof of Damages Remains an Obstacle". Vermont Journal of Environmental Law. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Satterfield, Jamie (December 22, 2018). "On 10th anniversary of Kingston coal ash spill, workers who went 'through hell and back' honored". Knoxville News-Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018.

- ^ "Dakota wind sites help TVA go green". Chattanooga Times Free Press. October 23, 2009. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Blockbuster Agreement Takes 18 Dirty TVA Coal-Fired Power Plant Units Offline". National Parks Conservation Association. April 14, 2011. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Flessner, Dave (January 8, 2018). "TVA cuts coal use". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Chattanooga, Tennessee. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "TVA Board Authorizes New Nuclear Program to Explore Innovative Technology". Tennessee Valley Authority. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ Flessner, Dave (August 12, 2018). "Protecting the power grid: TVA beefs up security as cyber threats grow". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Archived from the original on December 29, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Mufson, Steven (February 14, 2019). "TVA defies Trump, votes to shut down two aging coal-fired power plants". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 11, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Flessner, Dave (April 28, 2021). "TVA plans to phase out coal power by 2035 as utility turns to more gas, nuclear and renewable energy". Chattanooga Times Free Press. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Flessner, Dave. "TVA begins steps to shut down its biggest coal plant". EnergyCentral. Chattanooga Times Free Press. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ a b "Framatome signs multimillion-dollar contracts with Tennessee Valley Authority". Framatone. February 3, 2020. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ "Trump fires Tennessee Valley Authority chair over compensation, outsourcing". NBC News. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Derr, Emma (February 2022). "TVA Establishes New Nuclear Program". Nuclear Energy Institute. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "MLGW: No rolling blackouts after TVA rescinds order". WREG-TV. December 23, 2022. Archived from the original on December 23, 2022. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ "TVA ends rolling blackouts across East Tennessee". WJHL-TV. Johnson City, Tennessee. December 23, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ "Outages grow in Middle Tennessee, with some without power for hours". WTVF-TV. Nashville. December 23, 2022. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ Russell 1949, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Perlstein, Rick (2001). Before the storm: Barry Goldwater and the unmaking of the American consensus. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8090-2859-7. OCLC 801179619.

- ^ McCraw, Thomas K (1971). TVA and the power fight, 1933–1939. Critical periods of history. Philadelphia: Lippincott. p. 157. OCLC 162313.

- ^ a b O'Neill, Karen M. (June 2002). "Why the TVA Remains Unique: Interest Groups and the Defeat of New Deal River Planning". Rural Sociology. 67 (2): 163–182. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2002.tb00099.x. ISSN 0036-0112.

- ^ "Eisenhower Points to the T. V. A. As 'Creeping Socialism' Example". The New York Times. June 18, 1953. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Sturgis, Sue (April 16, 2013). "The strange politics of TVA privatization". Facing South. Durham, North Carolina: Institute for Southern Studies. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Harper, Liz. "Ronald Reagan – In Memoriam: Biography". NewsHour with Jim Lehrer online. PBS. Archived from the original on February 27, 2012.

In 1962, GE, concerned that Reagan's conservative politics made him a liability, fired him for criticizing the Tennessee Valley Authority as an example of 'big government.'

- ^ Weisberg, Jacob (January 8, 2016). "The Road to Reagandom: How Reagan's eight-year gig as the host of General Electric Theater sparked his conservative conversion and became the genesis of his political career". Slate. Archived from the original on July 18, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Moldea, Dan E. (March 15, 1987). "Ronald Reagan and his 1962 grand jury testimony". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Inquiry Dealt With Suspected Payoffs by Conglomerate: Book Says Reagan Was Cleared in '60s Probe of MCA". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. September 21, 1986. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Edwards, Lee (1995). Goldwater: The man who made a revolution. Washington, D.C.: Regnery. ISBN 978-0-89526-471-8. OCLC 624456231.

- ^ Mark, David (2007). Going dirty: The art of negative campaigning. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7425-9982-6. OCLC 396994651.

- ^ Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288 (1936), archived from the original.

- ^ Rodgers, Paul (2011). United States Constitutional Law: An Introduction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7864-6017-5. OCLC 707092889.

- ^ Ezzell, Timothy (2009). "Jo Conn Guild". Guild, Jo Conn. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ^ "Sex-Discrimination Action Moved Here". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. February 29, 1984. p. B7. Archived from the original on May 17, 2023. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ "TVA discrimination suit settled". Kingsport Times-News. United Press International. March 14, 1987. p. 3A. Archived from the original on May 17, 2023. Retrieved May 17, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Robinson, Bonnie (April 26, 1942). "Historic Bean Station, Oldest House in This Section, Fine Homes, and Other Landmarks Will Disappear in Cherokee Dam Lake". Knoxville News Sentinel. p. 26. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Onion, Rebecca (September 5, 2013). "The Tennessee Valley Authority vs. the Family That Just Wouldn't Leave". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ "TVA". Tennessee Historical Society. March 13, 2017. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ McMahan, Carroll (November 23, 2020). "Douglas Dam construction created controversy, displaced families". The Mountain Press. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Jefferson Chapman, Tellico Archaeology: 12,000 Years of Native American History (Tennessee Valley Authority, 1985).

- ^ Vicki Rozema, Footsteps of the Cherokees: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation (Winston-Salem: John F. Blair), 135.

- ^ Medina, Eduardo; Rubin, April (April 4, 2023). "Remains of Nearly 5,000 Native Americans Will Be Returned, U.S. Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ Madden, Tom (July 2, 1981). "Private land TVA claimed for lake to be given away to developers". UPI. Boca Raton, Florida. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ "Wild River 50th Anniversary Celebration Plans". The Chattanoogan. April 29, 2010. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Nelson, S. Tremaine. "Deliverance Revisited: Its relevance to modern American culture is enough to give alumnus James Dickey's acclaimed novel another look". Vanderbilt Magazine. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 19, 1984). "FILM: Farmers' Plight in The River". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- ^ Cavanaugh, Tim (March 2001). "O Big Brother, Where Art Thou?". Reason. Los Angeles: Reason Foundation. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "'Song of The South': The Story Behind Alabama's Smash Hit". Wide Open Country. Publishers Clearing House. July 24, 2020. Archived from the original on May 17, 2023. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ Opperman, Jeff (December 6, 2021). "Dams, Rivers And Drive-By Truckers: Songs That Explain The Challenge Of Sustainable Energy". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 17, 2023. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

Bibliography

edit- Barde, Robert E. "Arthur E. Morgan, First Chairman of TVA" Tennessee Historical Quarterly 30#3 (1971), pp. 299-314 online Archived March 16, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Colignon, Richard A. (1997). Power Plays: Critical Events in the Institutionalism of the Tennessee Valley Authority. SUNY series in the sociology of work. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-585-07708-6. OCLC 42855981.

- Creese, Walter L. (1990). TVA's public planning: The vision, the reality. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-638-7. OCLC 476873440 – via Internet Archive.

- Culvahouse, Tim, ed. (2007). The Tennessee Valley Authority: Design and persuasion. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. OCLC 929309559.

- Hargrove, Erwin C.; Conkin, Paul K., eds. (1983). TVA: Fifty years of grass-roots bureaucracy. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01086-6. OCLC 474377514 – via Internet Archive.

- Hargrove, Erwin C. (1994). Prisoners of myth: the leadership of the Tennessee Valley Authority, 1933–1990. Princeton Studies in American Politics: Historical, International, and Comparative Perspectives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03467-6. JSTOR j.ctt7rvbh – via Internet Archive.

- Kull, Donald C. (Winter 1949). "Decentralized Budget Administration in the Tennessee Valley Authority". Public Administration Review. 9 (1): 30–35. doi:10.2307/972660. ISSN 0033-3352. JSTOR 972660. OCLC 5544417850.

- Lilienthal, David E. (1953). TVA: Democracy on the march. New York: Harper & Row – via Internet Archive.

- Morgan, Arthur E. (1974). The making of the TVA. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-0-87975-034-3. OCLC 607606121 – via Internet Archive.

- Neuse, Steven M. (1996). David E. Lilienthal: The Journey of an American Liberal. Knoxville, Tennessee: The University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-940-8. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Neuse, Steven M. (2004). "Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)". In McElvaine, Robert S. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Great Depression. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Macmillan Reference USA.

- Neuse, Steven M. (November–December 1983). "TVA at Age Fifty—Reflections and Retrospect". Public Administration Review. 43 (6): 491–499. doi:10.2307/975916. ISSN 0033-3352. JSTOR 975916. OCLC 5550047671.

- Neuse, Steven M. (1996). David E. Lilienthal: the journey of an American liberal. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-940-1. OCLC 243857932.

- Russell, Dean (1949). The TVA idea. Irvington-on-Hudson, New York: Foundation for Economic Education. OCLC 564022. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Talbert, Roy Jr. (1987). FDR's Utopian: Arthur Morgan of the TVA. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 0-87805-301-8. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Wilson, Marshall A. (1982). Tales From the Grass Roots of TVA, 1933-1952. Knoxville, Tennessee: Wilson Publishing. OCLC 1011650240.

External links

edit- Official website

- Tennessee Valley Authority in the Federal Register

- Tennessee Valley Authority (March 1950). – via Wikisource.

- WPA Photographs of TVA Archaeological Projects

- The New Deal and TVA on YouTube

- Papers of Arnold R. Jones (Member of the Board of Directors, Tennessee Valley Authority), Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- TVA history

- The short film Valley of the Tennessee (1944) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.