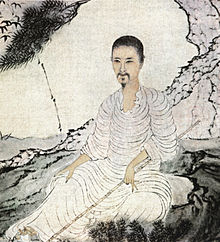

Shitao or Shi Tao (simplified Chinese: 石涛; traditional Chinese: 石濤; pinyin: Shí Tāo; Wade–Giles: Shih-t'ao; other department Yuan Ji (Chinese: 原濟; Chinese: 原济; pinyin: Yuán Jì), 1642 – 1707), born into the Ming dynasty imperial clan as Zhu Ruoji (朱若極), was a Chinese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and landscape painter during the early Qing dynasty.[1]

Born in the Quanzhou County in Guangxi province, Shitao was a member of the royal house descended from the elder brother of Zhu Yuanzhang. He narrowly avoided catastrophe in 1644 when the Ming dynasty fell to invading Manchus and civil rebellion. Having escaped by chance from the fate to which his lineage would have assigned him,[2] he assumed the name Yuanji Shitao no later than 1651 when he became a Buddhist monk.

He moved from Wuchang, where he began his religious instruction, to Anhui in the 1660s. Throughout the 1680s he lived in Nanjing and Yangzhou, and in 1690 he moved to Beijing to find patronage for his promotion within the monastic system. Frustrated by his failure to find a patron, Shitao converted to Daoism in 1693 and returned to Yangzhou where he remained until his death in 1707. In his late years, he is said to have greeted the Kangxi Emperor while the latter was visiting Yangzhou.

Names

editShitao used over two dozen courtesy names during his life. Both like and unlike Bada Shanren, his feelings for his family history can be deeply felt from these.[3]

Among the most commonly used names were Shitao (Stone Wave – 石涛), Daoji (道濟; Tao-chi), Kugua Heshang (Bitter Gourd Monk – 苦瓜和尚), Yuan Ji (Origin of Salvation – 原濟), Xia Zunzhe (Honorable Blind One – 瞎尊者, blind to worldly desires), Da Dizi (The Cleansed One – 大滌子).

As a Buddhist convert, he was also known with the monastic name Yuan Ji (原濟).[4]

Da Dizi was taken when Shitao renounced his Buddhist faith and turned to Daoism. It was also the name he used for his home in Yangzhou (Da Di Hall – 大滌堂).

Art

editShitao is one of the most famous individualist painters of the early Qing years. The art he created was revolutionary in its transgressions of the rigidly codified techniques and styles that dictated aesthetics at the time. Imitation was valued over innovation, and although Shitao was clearly influenced by his predecessors (namely Ni Zan and Li Yong), his art breaks with theirs in several new and fascinating ways.

His formal innovations in depiction include drawing attention to the act of painting itself through his use of washes and bold, impressionistic brushstrokes, as well as an interest in subjective perspective and the use of negative or white space to suggest distance. Shi Tao's stylistic innovations are difficult to place in the context of the period. In a colophon dated 1686, Shitao wrote: "In painting, there are the Southern and the Northern schools, and in calligraphy, the methods of the Two Wangs (Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi). Zhang Rong (443–497) once remarked, 'I regret not that I do not share the Two Wangs' methods, but that the Two Wangs did not share my methods.' If someone asks whether I [Shitao] follow the Southern or the Northern School, or whether either school follows me, I hold my belly laughing and reply, 'I always use my own method!'"[5][note 1]

Shitao wrote several theoretical works, including Sayings on Painting from Monk Bitter Gourd (Kugua Heshang). He repeatedly stressed the use of the "single brushstroke" or the "primordial line" as the root of all his painting. He uses this idea in the thin sinuous lines of his painting. The large blank areas in his work also serve to distinguish his unique style.[6] Other important writings include the essay Huayu Lu (Round of Discussions on Painting) where he repeats and clarifies these ideas, and also compared poetry to painting. He aimed to use paint to transmit the message of Chan Buddhism without the use of words.[7]

The poetry and calligraphy that accompany his landscapes are just as beautiful, irreverent, and vivid as the paintings they complement. His paintings exemplify the internal contradictions and tensions of the literati or scholar-amateur artist, and they have been interpreted as an invective against art-historical canonization.

10,000 Ugly Inkblots

editThe 10,000 Ugly Inkblots is a perfect example of Shitao's subversive and ironic aesthetic principles. This uniquely apperceptive work challenges accepted standards of beauty. As the carefully painted landscape degenerates into Jackson Pollock-esque splatters, the viewer is forced to recognize that the painting is not transparent (immediate, in the most literal sense meaning without media) in the way it initially purports to be. Solely because they are labeled "ugly," the ink dots begin to take on a sort of abstract beauty.

Reminiscences of Qinhuai

editThe Reminiscences of Qinhuai is another of Shitao's unique paintings. Like many of the paintings from the late Ming dynasty and early Manchurian sovereignty it deals with man's place in nature. Upon a first viewing, however, the craggy peak in this painting seems somewhat distorted. What makes this painting so unique is that it appears to depict the mountain bowing. A monk stands placidly on a boat that floats along the Qin-Huai river, staring up in admiration at the genuflecting stone giant. The economy of respect that circulates between man and nature is explored here in a sophisticated style reminiscent of surrealism or magical realism, and bordering on the absurd. Shitao himself had visited the river and the surrounding region in the 1680s, but it is unknown whether the album that contains this painting depicts specific places. Re-presentation itself is the only way the feeling of mutual respect that Shitao depicts in this painting could be communicated; the subject of a personified mountain simply defies anything simpler. Shitao also painted other "reminiscences" in this style, including "Reminiscences of Nanjing" that reinforced his legacy.

Notes

edit- ^ Paraphrased. The colophon was added to a 1667 hanging scroll of Huang Shan.

Footnotes

edit- ^ Hay 2001, pp. 1, 84

- ^ His uncle remained in Guilin as the Prince of Jingjiang and took the fate of committing suicide when (a traitor of Ming China) general Kong Youde assaulted the lineage's homeland in the name of Qing in 1650.

- ^ Coleman 1978, pp. 127

- ^ China: five thousand years of history and civilization. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press. 2007. p. 761. ISBN 978-962-93-7140-1.

- ^ Hay 2001, pp. 243, 250

- ^ Gardner, Helen; Kleiner, Fred S.; Mamiya, Christin J. (2005). Gardner's art through the ages (12th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth. ISBN 0-15-505090-7. OCLC 54830091.

- ^ "Shitao | Chinese painter". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

References

edit- Coleman, Earle (1978). Philosophy of Painting by Shih-T'Ao: A Translation and Exposition of His Hua-P'u (Treatise on the Philosophy of Painting) (Studies in Philosophy). The Hague: de Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-9027977564.

- Hay, Jonathan (2001). Shitao: Painting and Modernity in Early Qing China. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521393423.

Further reading

edit- Hinton, David (2016). Existence: A Story. Boulder: Shambhala. ISBN 9781611803389.

External links

edit- Shitao's painting gallery at China Online Museum

- Works

- Landscapes Clear and Radiant: The Art of Wang Hui (1632-1717), an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Shitao (see index)