Tell es-Safi (Arabic: تل الصافي, romanized: Tall aṣ-Ṣāfī, "White hill"; Hebrew: תל צפית, Tel Tzafit) was an Arab Palestinian village, located on the southern banks of Wadi 'Ajjur, 35 kilometers (22 mi) northwest of Hebron which had its Arab population expelled during the 1948 Arab–Israeli war on orders of Shimon Avidan, commander of the Givati Brigade.[4]

Tell es-Safi

تلّ الصافي Tel Tzafit | |

|---|---|

| |

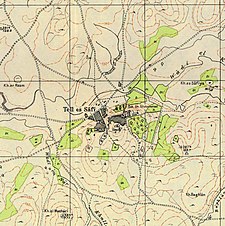

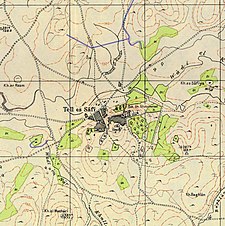

A series of historical maps of the area around Tell es-Safi (click the buttons) | |

Location within Israel | |

| Coordinates: 31°42′15″N 34°50′49″E / 31.70417°N 34.84694°E | |

| Palestine grid | 135/123 |

| Geopolitical entity | Israel |

| Subdistrict | Hebron |

| Date of depopulation | 9–10 July 1948[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 27,794 dunams (27.794 km2 or 10.731 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 1,290[1][2] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

Archaeological excavations show that the site (a tell or archaeological mound) was continuously inhabited since the 5th millennium BCE.[5] It appears on the Madaba Map as Saphitha, while the Crusaders called it Blanche Garde.[6][7] It is mentioned by Arab geographers in the 13th and 16th centuries. Under the Ottoman Empire, it was part of the district of Gaza. In modern times, the houses were built of sun-dried brick. The villagers were Muslim and cultivated cereals and orchards.

Today the site, known as Tel Tzafit, is an Israeli national park incorporating archaeological remains which some have identified as the Philistine city of Gath, mentioned in the Bible.[8] The remains of the Crusader fort and the Arab village can also be seen on the tell.[5]

Names

editThe 6th-century Madaba Map calls it Saphitha.[6][7] In the 19th century the white chalk cliff at the site was seen as the cause for the Arabic name: Tell es-Safi means "clear or bright mound".[9] The name used in the Crusader period was Blanche Garde, the "White Fortress" in French, and Alba Specula or Alba Custodia Latin.[10]

Geography

editTell es-Safi sits on a site 300 feet (91 m) above the plain of Philistia and 700 feet (210 m) above sea level, and its white-faced precipices can be seen from the north and west from several hours distant.[8] Tell es-Safi is situated between the Israeli cities of Ashkelon and Beit Shemesh and is one of the country's largest Bronze and Iron Age sites.[11]

Identification with Gath

editVictor Guérin thought that Tell es-Safi was the "watch-tower" mentioned in Joshua 15:38, based on its etymological meaning,[12] but the site is now believed to be the site of the Philistine city of Gath. The identification was opposed by Albright, who noted its proximity to another leading city from the Philistine league, Ekron (Tel Miqne), but later excavations turned up more supportive evidence for Tell es-Safi.[13][14][15]

Schniedewind writes that Gath was important for the Philistines in the eighth century BCE because of its easily defended geographical position. Albright argued that Tell es-Safi was too close to Tel Miqne/Ekron to be Gath. The sites are only 8 km apart. However, both Tell es-Safi and Tel Miqne were major sites in the Middle Bronze through the Iron Age. The agricultural features of this region of the southern coastal plain may be part of the explanation. Additionally, there is no certainty that the two sites flourished simultaneously. Literary sources suggest that Gath flourished in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages until its destruction by the Assyrians in the late eighth century BCE. The heyday of Ekron was the seventh century BCE, after the site was taken over by the Assyrians as an agricultural administrative center (Dothan and Gitin 1993).[16]

History and archaeology

editExcavations at Tell es-Safi since 1996[11] indicate that the site was settled "virtually continuously from the Chalcolithic until the modern periods."[5]

Bronze Age

editCanaanite city

editThe site was already a significant settlement in the Early Bronze Age with an estimated area of 24 hectares. Finds from this period include a hippopotamus ivory cylinder seal, found inside a holemouth jar in a well stratified EB III (c. 2700/2600 – 2350 BCE) context. The motif was that of a crouching male lion.[17][18]

Stratigraphic evidence attests to settlement in the Late Bronze and Iron Age (I & II) periods.[5] By the Late Bronze Age the site had reached an extent of 34 hectares. A find of a hieratic inscribed LBA bowl fragment (19th - 20th Dynasty) reflects the Egyptian contacts common in this region during this period.[19]

Iron Age

editPhilistine presence

editThere is stratigraphic evidence for settlement in the Iron Age I & II periods.[5] A large city in the Iron Age, the site was "enclosed on three sides by a large man-made siege-moat."[20]

Radiocarbon dating published in 2015 showed an early appearance of Philistine material culture in the city.[21] According to 2010 reports, Israeli archaeologists uncovered evidence of the first Philistine settlement in Canaan, as well as a Philistine temple and evidence of a major earthquake in biblical times.[22]

The Tell es-Safi inscription, dated to the 10th century BCE, was found at the site in 2005.

Archaeologists have discovered a horned altar dating to the 9th century BCE. The stone artefact is over 3 feet (one meter) tall, and is the earliest ever found in Philistia. It features a pair of horns, similar to the ancient Israelite altars described in the Hebrew Bible (Exodus 27:1–2; 1 Kings 1:50), the Israelite altars however typically have four horns, such as found in Tel Be'er Sheva, for example, as opposed to two.[23]

The 2010 reports mention evidence of destruction by King Hazael of Aram-Damascus around 830 BCE.[22]

Byzantine period

editThe place appears on the Madaba Map as Saphitha (Greek: CΑΦΙΘΑ).[6]

Crusader and Ayyubid period

editDuring the Crusades, the site was called Blanchegarde, ("White guard"), likely referring to the white rock outcrop next to the site.[24] In 1142, a fort was built on the site by King Fulk. After the Siege of Ascalon in 1153, the castle was expanded and strengthened.[25] It became a lordship in 1166, when it was given to Walter III Brisebarre, lord of Beirut.

It was dismantled after being taken by Saladin in 1191,[24][26] but reconstructed by Richard of England in 1192. King Richard was nearly captured while inspecting his troops next to the site.[24]

In 1253, Gilles' son Raoul (died after 1265) was documented as lord of Blanchegard. In 1265, the Baron Amalric Barlais, who was loyal to the Hohenstaufen, took over the rule of Blanchegard.[27] Shortly thereafter Blanchegard was retaken by Muslim forces. The remnants of the square castle and its four towers served as a place of some importance in the village well into the 19th century.[8][28][29]

Yaqut al-Hamawi, writing in the 1220s, described the place as a fort near Bayt Jibrin in the Ramleh area.[24][30]

Mamluk period

editThe Arab geographer Mujir al-Din al-Hanbali noted around 1495 that a village by this name was within the administrative jurisdiction of Gaza.[24][31]

Ottoman period

editThe village was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517 with all of Palestine, and in 1596 it appeared in the tax registers being in the nahiya (subdistrict) of Gaza under Gaza Sanjak, with a population of 88 Muslim households; an estimated 484 persons. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on a number of crops, including wheat, barley and sesame, and fruits, as well as goats and beehives; a total of 13,300 akçe.[32]

In 1838 Edward Robinson described Tell es-Safieh as a Muslim village in the Gaza district.[33] It was "an isolated oblong hill or ridge, lying from N.to S. in the plain, the highest part being towards the South. The village lies near the middle; lower down."

The Sheikh, Muhammed Sellim, belonged to the 'Azzeh family of Bayt Jibrin. After his family took part in the Peasants' Revolt of 1834, his father and uncle were beheaded and the remaining family was ordered to take up residence at Tell es-Safi.[34]

When Victor Guérin visited in 1863, he saw two small Muslim walīs.[35] An Ottoman village list drawn up around 1870 counted 34 houses and a population of 165 men.[36][37]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Tell al-Safi as a village built of adobe brick with a well in the valley to the north.[38] James Hastings notes that the village contained a sacred wely.[8]

In 1896, the population was around 495 persons.[39]

British Mandate

editIn the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Tal al-Safi had a population of 644 inhabitants, all Muslims,[40] increasing in the 1931 census to 925, still all Muslim, in a total of 208 inhabited houses.[41]

The villagers of Tall al-Safi had a mosque, a marketplace, and a shrine for a local sage called Shaykh Mohammad. In the 1945 statistics, the total population was 1,290, all Muslims,[2] and the land area was 27,794 dunams of land.[1] Of this, a total of 19,716 dunums of land were used for cereals, 696 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[42] while 68 dunams were classified as built-up (urban) areas.[43]

Israel

edit1948 war

editIn 1948, Tell es-Safi was the destination for the women and children of Qastina, sent away by the menfolk of Qastina at this time, but they returned after discovering there was insufficient water in the host village to meet the newcomers' needs.[44]

On 7 July Givati commander Shimon Avidan issued orders to the 51st Battalion to take the Tall al-Safi area and "to destroy, to kill and to expel [lehashmid, leharog, u´legaresh] refugees encamped in the area, in order to prevent enemy infiltration from the east to this important position."[45] According to Benny Morris, the nature of the written order and, presumably, accompanying oral explanations, probably left little doubt in the battalion OC's minds that Avidan wanted the area cleared of inhabitants.[46][47]

Arab village remains

editIn 1992, Walid Khalidi wrote that the site was overgrown with wild vegetation, mainly foxtail and thorny plants, interspersed with cactuses, date-palm and olive trees. He noted the remains of a well and the crumbling stone walls of a pool. The surrounding land was planted by Israeli farmers with citrus trees, sunflowers, and grain. A few tents belonging to Bedouin were occasionally pitched nearby.[24]

National park

editThe site is now an Israeli national park and the site of ongoing archaeological excavations.[48]

Archaeological exploration

editThe site was visited in 1875 by Claude Reignier Conder who was impressed with its height and position in the landscape but not impressed by the "insolent peasants". The only visible remains were those of the Crusader era fortress.[49]

The first excavations at the site began in 1899 when Frederick J. Bliss and R. A. Stewart Macalister worked for three seasons on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. While in the early days of archaeology the methods of Bliss were reasonably advanced for those days. The excavation failed in its primary goal of firmly identifying the site as Gath but did properly work out the stratigraphy.[50][51][52][53][54][55]

In the 1950 and 1960s Moshe Dayan conducted illegal digs at Tell es-Safi and other sites. Some of the robber holes can still be seen at the site today. Many of the objects from these digs ended up at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.[56]

Since 1996 the site has been excavated by the Tell es-Safi/Gath Archaeological Project led by Aren Maeir.[57][58]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 50

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 23

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xix, village number #292. Also gives cause of depopulation

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 436

- ^ a b c d e Negev and Gibson (2005), p. 445.

- ^ a b c Kallai-Kleinmann (1958), p. 155

- ^ a b Tsafrir (1994), p. 134

- ^ a b c d Hastings and Driver, 2004, p. 114

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 275

- ^ Boas, Adrian J.; Maeir, Aren M. (2016) [2009]. "The Frankish Castle of Blanche Garde and the Medieval and Modern Village of Tell es-Safi in the Light of Recent Discoveries". In Benjamin Z. Kedar; Jonathan Phillips; Jonathan Riley-Smith (eds.). Crusades. Vol. 8. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7546-6709-4. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ a b Sutton, Mark Q. (2015). Archaeology: The Science of the Human Past (4 ed.). Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 9781317350095. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Guérin, V. (1869), p. 90–ff.

- ^ Gath in the Bible gath.wordpress.com

- ^ Bromiley, 1982, pp. 411-413

- ^ Harris, Horton (2011). "The location of Ziklag: a review of the candidate sites, based on Biblical, topographical and archaeological evidence". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 143 (2): 119–133. doi:10.1179/003103211x12971861556954. S2CID 162186999.

- ^ William M. Schniedewind, The Geopolitical History of Philistine Gath. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 309 (Feb., 1998), pp. 69–77

- ^ Maeir, Aren M., et al. "'Like a Lion in Cover': A Cylinder Seal from Early Bronze Age III Tell Eṣ-Ṣafi/Gath, Israel." Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 61, no. 1, 2011, pp. 12–31.

- ^ [1]Ross, J., et al. "In search of Early Bronze Age potters at Tell es-Safi/Gath: A new perspective on vessel manufacture for discriminating chaines operatoires". Archaeological Review from Cambridge, vol. 35, 2020, pp. 74-89.

- ^ Wimmer, Stefan J., and Aren M. Maeir. "'The Prince of Safit?': A Late Bronze Age Hieratic Inscription from Tell Eṣ-Ṣāfi/Gath." Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins, vol. 123, no. 1, 2007, pp. 37–48.

- ^ Wigoder, 2005, pp. 348–9.

- ^ Radiocarbon Dating Shows an Early Appearance of Philistine Material Culture in Tell Es-Safi/Gath, Philistia, University of Melbourne

- ^ a b "In the Spotlight", Jerusalem Post, 29 July 2010.

- ^ Maeir, Aren (January–February 2012). "Prize Find: Horned Altar from Tell es-Safi Hints at Philistine Origins". Biblical Archaeology Review. 38 (1): 35.

- ^ a b c d e f Khalidi, 1992, p. 222

- ^ "Crusader History – On a crusade". The Jerusalem Post. 26 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-08-26.

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 440

- ^ Charles D. Du Cange (1971). Les Familles D'Outre-Mer. Ayer Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 0833709321.

- ^ Pringle, 1997, p. 93

- ^ Rey, 1871, pp. 123-125; illustrated

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p.544

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 41

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 150. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 222

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 119

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, pp. 362-367

- ^ Guérin, 1869, pp. 90 −96

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 162

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 144 noted 80 houses

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, pp. 415 – 416 Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 222

- ^ Schick, 1896, p. 123

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Hebron, p. 10

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 34

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 94. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, 222

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 144

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 176

- ^ Givati, Operation An-Far, 7 July 1948, IDFA 7011\49\\1. Cited in Morris, 2004, p. 436. Also see note#127, p. 456 According to Morris, Avraham Ayalon (1963): The Givati Brigade Opposite the Egyptian Invader. pp. 227-28 "gives a laundered version of the order, – which I (unfortunately) used in the original edition of The Birth." The "laundered" version does not contain the words: "to destroy, to kill".

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 437

- ^ Operation An-Far

- ^ "Looking for a Wider View of History, Israeli Archaeologists Are Zooming In". Haaretz.

- ^ Conder, Claude Reignier. Tent work in Palestine: a record of discovery and adventure. AP Watt & Son, 1895

- ^ Bliss, F.J.; Macalister, R.A.S. (1902). Excavations in Palestine During the Years 1898–1900. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (pp. 28-43) - ^ Bliss, Frederick. J., 1899 "First Report on the Excavations at Tell es-Safi.", PEQSt 31: pp. 183–99

- ^ Bliss, F.J. (1899). "Second Report on the Excavations at Tell Es-Safi". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 31: 317-333.

- ^ Bliss, F.J. (1900). "Third Report on the Excavations at Tell Es-Safi". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 32: 16-86.

- ^ Bliss, Frederick J. "Fourth Report on the Excavations at Tell Zakarîya; Third Report on the Excavations at Tell es-Sâfi; List of Casts and Moulds." Palestine Exploration Quarterly 32.1 (1900): 7-29

- ^ Rona S. Avissar Lewis, and Aren M. Maeir. “New Insights into Bliss and Macalister’s Excavations at Tell Eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath.” Near Eastern Archaeology, vol. 80, no. 4, 2017, pp. 241–43, https://doi.org/10.5615/neareastarch.80.4.0241

- ^ Aren M. Maeir. “The Tell Eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Archaeological Project: Overview.” Near Eastern Archaeology, vol. 80, no. 4, 2017, pp. 212–31, https://doi.org/10.5615/neareastarch.80.4.0212

- ^ Aren Maeir, "Tell es-Safi/Gath I: The 1996–2005 Seasons.", Vol. 1: Text; Vol. 2: Plates. Ägypten und Altes Testament, vol. 69. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2012 ISBN 978-3-447-06711-9

- ^ Aren M. Maeir and Joe Uziel, "Tell es-Safi / Gath II: Excavations and Studies", Ägypten und Altes Testament, vol. 105, Zaphon, 2020 ISBN 978-3-96327-128-1

Bibliography

edit- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Bromiley, G.W. (1982). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Vol. II: E-J. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-3782-4.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1896). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. Vol. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. ( p.440. )

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hastings, J.; Driver, S.R. (2004). A Dictionary of the Bible: Volume II: (Part I: Feign – Hyssop). The Minerva Group, Inc. ISBN 9781410217240.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Kallai-Kleinmann, Z. (1958). "The Town Lists of Judah, Simeon, Benjamin and Dan". Vetus Testamentum. 8 (2). Leiden: Brill: 134–160. doi:10.2307/1516086. JSTOR 1516086.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Macalister, R.A.S. (1925). A century of excavation in Palestine. London: The Religious Tract Society. (pp. 51, 56, 59, 124, 189, 275)

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Negev, Avraham; Gibson, S. (2005). Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780826485717.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0. (pp. 291–292)

- Pringle, D. (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521-46010-7.

- Rey, E. G. [in French] (1871). Etude sur les monuments de l'architecture militaire des croisés en Syrie et dans l'île de Chypre (in French). Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Tsafrir, Y. (1994). Tabula Imperii Romanii: Iudaea, Palaestina [Maps and Gazetteer]. Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. ISBN 9789652081070.

- Wigoder, Geoffrey (2005). The Illustrated Dictionary and Concordance of the Bible. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 9781402728204.

- Wilson, C.W., ed. (c. 1881). Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt. Vol. 3. New York: D. Appleton.(p.158 -p.161 )

External links

edit- The Tell es-Safi/Gath Archaeological Project Official (and Unofficial) Weblog

- Tall-al-Safi Palestine Remembered

- Tall al-Safi, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 16: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Tall al-Safi, at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- New Technology Interprets Archaeological Findings from Biblical Times - Tel Aviv University